Bathsheba Demuth is an environmental historian, specializing in the lands and seas of the Russian and North American Arctic. She is the author of Floating Coast: An Environmental History of the Bering Strait, which was named a Nature Top Ten Book of 2019, listed as a Best Book of 2019 by NPR, Nature, Kirkus Reviews, and Library Journal, and winner of the 2020 George Perkins Marsh Prize. Her other writings can be found in The American Historical Review and The New Yorker.

Ecological historian Bathsheba Demuth explores the allure of the apocalyptic arc—the promise of a new world—and the rise and ruin of the Soviet ideology that sought to impose its utopian vision on the Native Chukchi people, their herds of reindeer, and the natural cycles of the Russian tundra.

The fox comes out of the willows across the creek. She is nearly invisible at first, standing in the lee of a sunbeam where it breaks over the ravine behind her. Early morning sun, late in a summer of intense heat. Here, twenty miles north of the Arctic Circle, the light is dilute, low on the horizon and stained orange by forest-fire smoke blown from the Siberian interior. The fox steps into the radiance. Stops. Her blue-gray summer pelt has loosened, tufts of shedding fur blooming a golden corona across her back. Below, a belly slack from recent pregnancy. Something fresh-killed and bloody—a lemming, judging from the short tail—droops from her jaws. She turns, the taut notice of her ears pivoting forward, and, for a moment, I am inside her attention.

I live often in the company of the dead, as historians do. Here, on the Chukchi Peninsula, so far east in Russia it is as close to Boston as to Moscow, I think of what the dead have told me about this place: August snow squalls, whipping cold and wind, ice on still water by September. Eye to eye with the fox, I am not even in a sweater. In this part of the Arctic, it is the hottest summer in recorded memory. All through June and July, people say offhand or with worry or with dark humor, “It’s the end of the world,” or “It’s Armageddon.” The first word of a widely read article about climate change is “Doomsday.” In a few weeks, scientists will give the world twelve years to reduce carbon emissions or risk warming so great it will be headlined “Climate Apocalypse.”

Behind me, the sound of a motor. Alex has started our uaz, a Soviet-era van with the soul of a tractor. We are going north, where the Chukchi reindeer brigades run their herds along the Amguema River. Alex has distant relatives there, to whom we are carrying supplies and gifts: biscuits, sugar, candles, bread, tinned butter, evaporated milk, boxes of tea, bags of hard candies. There are hours to go yet on the rutted gravel road. We stopped at this bubbling creek to do something Alex’s father taught him: pick a stem of grass and leave it in the water. A pros’ba, Alex called it. A request, or a prayer. A supplication to the future.

Then came the fox. The terms of her future, Alex’s future, my future, and the future of this place—and all the loved, life-filled places—are given so often now as prophecies of rupture. Years of historical training mean I cannot see the arc of such stories as neutral. They shape the borders of our minds, and our politics. I want to know: Where does it come from, this narrative of absolute end? And what meaning slinks in with a proclamation of apocalypse?

The fox lifts her nose at the engine sound, and turns. I watch her trot back to her kits: paws quick through the bearberries and knots of cotton grass before her path angles among crumbling buildings, cement gone porous with decades of rain, and machinery turned burnt red from rust. The fox does not give us a backward glance as she takes shelter in our ruins.

Ruins of a walrus-oil processing plant and other remnants of early Soviet construction.

Photos by Bathsheba Demuth

Soviet apartments and buildings in Ureliki, an abandoned military town.

Building

One of the dead in whose company I have passed some days is a man named Karl Yanovich Luks. He was dark-haired and handsome, from what the photographs tell. The fraying influence of cold winds was just beginning to show around his eyes when he wrote reports from Chukotka to Moscow in the 1920s:

The Chukchi are the majority of the Native population of the Chukchi Peninsula…. Under the tsars, these Natives were only of interest as suppliers of furs. Nobody gave a thought to protecting the base of the Native economy, to improving his way of life. As a result, the fur trade was nearly extinguished … and reindeer husbandry fell off catastrophically.

To fix this destruction is our task.

In Karl’s life is a history of apocalyptic allure, of what sings to us beyond the horizon of a demolished now. He was born on the western edge of the Russian Empire in 1888 to peasants so destitute his father nearly sold an infant Karl to the childless baron who owned the lands his parents worked. As a boy he tended cattle. Around him, most people were confined to agricultural toil on old noble estates or industrial toil in new factories. His parents were unable to afford education beyond basic literacy, so Karl became a deckhand when he was hardly more than a child.

One appeal of the apocalypse is that it can make those on its threshold feel world-historically important.

His voyages took him through Baltic ports thrumming with discontent. Strikers protested factories that rent their bodies. Bread lines turned into riots after days of hunger. Students demanded representative government. Tsar Nicholas II, heir to four centuries of autocratic rule, sheltered in his palaces, spent lavishly, and hired more police. The people Karl met outside these aristocratic walls found their present so unjust, so sickly, so impossible, their question was not would it end, but how. Karl heard Baptists preaching hellfire, Orthodox priests invoking the salvation of saints, and a dozen other sects calling down the final judgment.

As the historian Yuri Slezkine explains, these visions all shared a plot: first the apocalypse, then a reign of harmony and perfection. An old story, passed from the Middle East to Europe, from Jewish cosmologies into Christian traditions, going back almost three thousand years to the prophecies of Zoroaster, who foretold a cataclysmic battle between light and dark. The triumph of light would give the righteous a new life, one without suffering or toil, one where time as meted out in cycles of birth and death ended in a linear, immortal world.

Karl did not become a Baptist or worship saints. He joined a socialist reading circle. In Slezkine’s masterful reading of the Russian socialist condition, the plot Karl learned also came from Zoroaster’s lineage. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels foretold how the darkness of capitalist exploitation would become the light of communist utopia. Between these poles was a kind of earthly revelation: what socialists called revolution. A word, Slezkine reminds us, promising “the end of the old world and the beginning of a new, just one.”

I met Karl in an age-crumpled file in Vladivostok, where I learned what he would give for this new world. At seventeen, he was arrested for distributing illegal pamphlets. For the next decade, he was in and out of custody. Karl left a four-year term in Orel Central Penitentiary with tuberculosis. In his autobiography, Karl described being bound by a guard in a different prison: “the ropes ate into my body to the bones at hands and feet … [which] were swollen and blackened so it was impossible to control them.” When Vladimir Lenin brought the revolution to Russia in the bitterly cold and hunger-filled winter of 1917, Karl was in Siberian exile. He joined Lenin’s army when it reached the north, then he moved on to Chukotka, tasked by the new Soviet government with “liquidating the consequences of centuries-old historical injustices” from the tundra.

When Karl wrote, “To fix this destruction is our task,” what he meant was, “we shall end the unjust world, and beyond it is a life without want.” Such a pure vision: Karl went to prison and into exile to help found the kingdom of freedom on earth.

One appeal of the apocalypse is that it can make those on its threshold feel world-historically important.

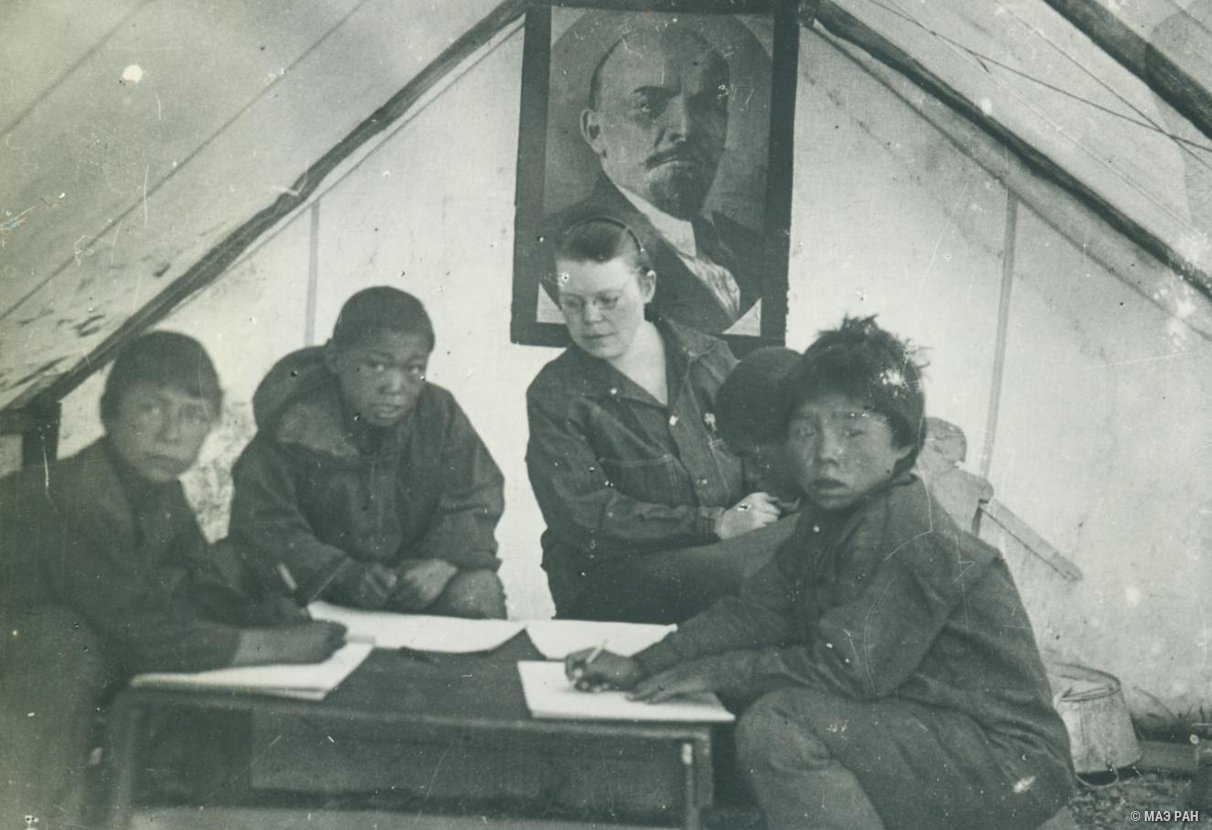

A Soviet Native school, likely in Chaplino.

Courtesy of Kunstkamera2

Back in the uaz, we climb through hills of eroding yellow and brown stone, their tops in velvet fog. The road turns out onto green rolling tundra. Somewhere to our north, Alex says, are the reindeer. Like the fox, they are in summer molt, flanks patchy with shedding hair and antlers trailing bloody ribbons of the velvet that nourished their bony growth. Reindeer are almost never alone, and almost never still. They move constantly to find fresh pasture and breezes to keep mosquitoes from tormenting their flesh. With each step the tendons in their hooves move over the sesamoid bone with a soft click. In other summers, on other tundras, I have heard reindeer before seeing them.

Today, the reindeer are with their people. Centuries before the first Russian speaker came here, the Chukchi and wild reindeer struck a bargain, in the relations we call domestication: reindeer who lived as familiars with people were protected from wolves and bears; people who lived as familiars with reindeer were protected from starvation. In the history the Chukchi tell of themselves, a few dozen domesticated reindeer made food and shelter newly dependable. Hundreds or thousands made politics newly potent, as the bodies of many reindeer carried the authority of many gifts and armies fed for war.

Yet to walk out with a herd on a tundra morning was to enter a world where human authority did not extend fully even to the tame animals shuffling their spade-like hooves and exhaling great steamy breaths outside Chukchi tents. These hills were home to many beings, to mushroom-shaped men, and giants with gaping mouths, and wild reindeer people, any of which could steal a herd. Some were kin, some were foes. Valleys, rivers, reindeer, foxes, walruses—all bore souls that required entreaty. That required you ask for their favor before you walk. Time itself spooled out through the land in cycles. A spate of warm years—normal, for most of the Holocene, each century to half-century—brought intertwined perils. Cold air reduces precipitation, so in warmer winters herds foundered in deep snow. Sometimes rain fell on the drifts, then froze again; the resulting ice starved reindeer unable to paw through it to the lichens and dried grass beneath. Boggy summers infected their hooves, hindered migration, and left them vulnerable to anthrax. A family with five thousand reindeer could in a decade find themselves with only hundreds: enough for food, not for armies. To walk out on an Arctic morning was always an appeal to a will-filled universe. For, as one Chukchi man told it not long after Karl Luks was born, “nothing created by man has any power.”

Karl would not have agreed. “Freedom,” Engels wrote in Anti-Dühring, “consists in the control over ourselves and over external nature.” Liberation came from bending every resource to human need, and only humans could be free. It was the fundamental plot for Marx and Engels: this capacity for progress that drew societies from hunting and gathering to agriculture, to industrial capitalism, and onward to revolution, beyond which there would be no suffering or decay. The idea of time Karl brought with him to Chukotka was aggressively linear.

On the tundra, Karl’s task was to identify external nature to control. Chukotka was too cold for agriculture, too distant and rugged for much industry. But there were reindeer with useful meat, and foxes with valuable pelts. Karl drew up plans to increase the size of reindeer herds with Soviet farming techniques. Other young “missionaries of the new culture and the new Soviet state,” as one follower of Marx put it, designed systems of fox pens and barns. The animals could not be left in the wild: out on the tundra, their numbers rose and fell every few years, dependent on cycles of lemmings. Socialist farms would replace such inconstancy with predictable growth. Caged foxes required no long days setting traps among the thickets that foxes prowl; the Chukchi could live in town, in apartments with electricity and running water, while their children, Karl wrote, could attend “a first class school not in Native dialect, for a real Soviet education.”

Karl did not ask the Chukchi if they wanted this new world. No one did. Nor did anyone ask the foxes about the pens or the reindeer about their corrals; to do so was not thinkable.

Another appeal of the apocalypse: proclaiming it is not an act of supplication, but of certainty.

Selecting reindeer to harness to heavy sleds.

Courtesy of Kunstkamera3

Woman sitting on a summer cover for a tent that she is sewing.

Courtesy of Kunstkamera4

An Elder and a young woman attaching a reindeer skin cover to a tent frame.

Courtesy of Kunstkamera5

In 1932 Karl Luks took an accidental bullet while surveying foxes and reindeer and other life on the Chaun River, in Chukotka’s northwest. As he bled to death, so Soviet reports go, he begged his fellow revolutionaries to continue their work “in the most remote places inhabited by Natives, … no matter the victims, in spite of any cost.”

Such certainty can be a kind of madness. In the uaz, bumping north, Alex tells me that many of the “victims” who came after Karl were Chukchi. “We did not want to live in the way the Soviets said was correct,” Alex explains. Looking west out the uaz, I see rocks covered in black lichen breaking through cushions of moss campion. A single white reindeer rib bone curves up from the pink flowers. Across the road, other remains: a pekaranya, a bakery, its roof like a broken back, crouched amid low houses charred by old fire. The way of life these structures built into the land—settled, electrified, educated in Russian—did not signal the promised land to Alex’s ancestors as it did for Karl. The Chukchi did not want to give their reindeer to Soviet farms and take day-long shifts in dark fox barns. Or give over their visions of creation—the raven that made their land, long ago, or the boy born from a reindeer’s ear—for the stories Lenin told.

For two decades after Karl died, war simmered over the tundra. The Chukchi killed their reindeer or killed themselves rather than be part of the new promised land. Around and after the violence, Soviet scientists mapped these hills and rivers, analyzed their plants, plotted migration routes to optimize reindeer nutrition. Veterinarians inoculated herds for anthrax and foxes for distemper, examined hooves for disease, and charted the best time to breed vixens. The tundra was coming under control—was becoming the prophesied human perfection. One reindeer scientist even wrote in the 1950s that the revolution had brought such “new forms of organizing the reindeer herd” that growth would be infinite. The ultimate linear dream, of progress unending: an escape from the limits of moss and lichen, the necessity of relating to other life.

Something else about the apocalypse: its battles only damn or save human beings. In this story, our species has no kin but ourselves.

Falling

We reach the Amguema by midday. A quarter mile or so from its banks is a village, named after the river. A Soviet town, concrete buildings connected by elevated gas pipes shedding insulation. Entropy has taken over on the outskirts, pulling down houses, filling the space between with fireweed. But in the center, there are curtains in open windows and bright paint on the concrete. Somewhere, Pearl Jam is playing, tinny notes floating towards us on the breeze: A dissident is here. Escape is never the safest path.

We stop the uaz by a group of men in rubber boots and mud-spattered orange overalls. One of them introduces himself as the mayor. They are digging a drainage ditch, he explains. The tundra under the town is seeping. Alex asks if the reindeer brigades are close. The mayor points us west, toward the river. If they have returned, their yaranga, their reindeer-hide tents, will be there. He advises that we leave the uaz and walk: since the fall, the roads have decayed.

What presence will we be for the lives that come after us?

The fall: sixty years after Karl Luks died, the Soviet Union ceased to exist. By then, in the early 1990s, socialist efforts to control this land had changed many things—built these roads and apartments, brought children into schools, herded reindeer with helicopters and snow machines. Chukotka became a Soviet version of the world we now find normal, where lights come on with a switch and airplanes satisfy any need. But the Soviet Union never did mold time into linear form. Even before the USSR sundered, reindeer herds defied Soviet prophecy and declined. Foxes kept dying from rabies. The impossibility of Karl’s most apocalyptic promise—the freedom from any natural constraint—was borne out. And then what did change disappeared.

Historians tell stories of why. In Chukotka, the stories of the 1990s bend toward the how. How did we survive a civilization in its ending? All that the Soviets brought with them—the gas heat and bakeries, the machinery and medicines—was no more. Alex was a child when the electricity stuttered off. There was no gasoline to move supplies, but there were no supplies to move anyway.

The arrival of the Soviet Union had been terrible for its violence; its dissolution was terrible for its sudden stillness. Towns were emptied as people fled to southern Russia. Older people died without medicine or warmth. Mothers worried that lack of food meant little milk for their infants. Everything was cold. The horizon of time closed: What would summer bring to keep families and whole towns alive during the winter? What would winter do? The fox barns emptied. Untended reindeer went feral or were lost to wolves.

Yet each day came with its small, specific tasks of survival. Chukchi families set up yaranga inside their apartments and burned seal oil lamps for warmth and light. Through summer and fall, people picked berries and greens and packed them in seal fat for winter. It was good to know hunters who lived along the coast, in the villages where Elders still remembered how to kill bowhead whales without specialized equipment. It was also good to know how to tend reindeer without helicopters, sew reindeer-hide boots, harness a reindeer when the snow machine ran out of fuel. Solidarity, that old socialist refrain, ceased to be a slogan and became a necessity. At the end of a world, there are no damned or saved souls, only people and other kin to share in the work of making life possible.

No one knew what would happen, Alex tells me. The trick to surviving was in knowing something about the land and the animals, and in keeping on without certainty.

Fireweed blooming in the disturbed soil of Shaktorskii, an abandoned Soviet coal mining town.

Photo by Bathsheba Demuth

The reindeer are still at pasture: none are to be seen as we pick our way over the uneven ground with our parcels of bread and biscuits. Ahead is the Amguema River, bright blue in the midday light, breaking silver in the shallows. On the bank, among low willows, are two yaranga, round and white like landed clouds. A dog, waist-high and furred like a bear, rises at our approach and nuzzles my hand. Alex calls out hellos. From within one of the tents, a voice asks if we want tea.

Stooping into the yaranga, I am blinded for a moment by smoke, which rises from a small fire, its coals sheltering a blackened pot. Near the coals are an older man and woman: Grigori and Anna, they say. We give our names and sit cross-legged on reindeer skins, passing over our gifts in exchange for tea, brewed oily black and dense with sugar.

The conversation loops between Russian and Chukchi, so I do not understand all of it. There are relatives to discuss. News from wider Russia to pass on: what Putin is doing in Moscow. I catch that Grigori and Anna were born just after the Chukchi and the Soviets ceased killing each other, and were nearly grandparents by the collapse. Their sons work in Amguema part of the year but are out now with the reindeer. They sell some of the meat in Chukotka’s larger towns and keep the rest, along with the skins, for their relatives.

The tundra where the reindeer graze has grown strange. There are new insects, Grigori says, beetles the Chukchi have no words for and which eat some of the same plants as reindeer. Anna is worried about chemicals and cancer: from what the Soviets left behind, but also from the garbage she says washes up on the Bering Sea coast after every storm. What does it leech into the fish we all eat from this river? And then there is the weather. Deep snow, rains that come late into fall for the past few years. We all look down at our tea. No one knows what’s going to happen, Grigori says. It’s probably a good idea to buy more rubber boots, he adds, and laughs.

Today it is hard to say when the reindeer will come back, Anna says. It depends on the winds and the pastures, and if there is rain. The herds have their own plans, so we should eat boiled meat and stay and talk. She puts a larger pot on the fire. Grigori opens a worn Styrofoam cooler, its interior full of red flesh and blood smell, and with a long knife begins to sever reindeer ribs from each other.

At the end of a world, there are no damned or saved souls, only people and other kin to share in the work of making life possible.

When the smoke from the fire begins to sting my eyes, I slip out of the tent and walk toward the river. From the far bank, the country rolls out in a wide plain, lustrous green with summer growth, the hummocks and knots of sedge grass and boggy places smoothed by distance. Far off, low mountains rise purplish. On this afternoon, I am almost the same age Karl Luks was when he wrote “to fix this destruction is our task.” We have other things in common. I also came of age—I am of age—in a world too precarious and unjust to continue with impunity. People with power spend lavishly and hire more police. In the United States, where I live, our national politics leads less to the poor selling their children to the wealthy than to the wealthy stealing children’s futures, carbon atom by carbon atom. All around are whispers of the end: we live in late capitalism, people say, implying imminent sundown; we live in the sixth extinction, people say, calling up the void with a phrase; we live in a climate emergency, a crisis, a thing terribly more than change. The grimmest of these prophecies tells an old story: the ultimate battle, in which an unlivable climate will drive out the darkness that we have become. As if the end to human failing is our extinction.

The core of apocalyptic thinking is nihilism: this world is too despoiled to continue. The seduction of such stories is how certain they make the teller feel. An apocalyptic narrative is like looking at a horizon with no clouds or hills: the way forward is terribly assured. To walk it, there is no need to mind the lives of others, rendered invisible by the power of imagining they are already gone.

Apocalyptic prophecy is also an escape from contemplating—from seeing in the here and now—how life goes on even through catastrophe. The Chukotkan riverbank where I am standing has borne two world-endings in the past century, the end of a world without socialists and the end of a world with them. The story these endings have etched into this earth bears no relation to Zoroaster’s final battle, or the pure cleansing fire of Karl’s revolution. What the land here speaks instead is a tale in which rupture is never complete. No revolution excises the quotidian, the need to rise and sleep, to nourish and shelter, to care for new birth and imminent deaths. This is the insurmountable stuff of being. In the company of Chukotka’s dead and living, I have come to believe the most terrifying thing about our future is not just what will change or cease or grow uncanny, but what must continue regardless.

Looking out toward the far mountains, I think of the drive here. Almost a hundred kilometers, the road marked by sequential clots of debris. Rusted things, broken things, shelters opened to the sky. One way to see Chukotka is as unrelentingly scarred, a place befouled by Soviet remnants. Another way is as a site of ongoing restitution. The mayor down in the mud, making another year livable in his town. A reindeer rib, feeding us. The fox raising a new generation inside a lidless, rusted oil barrel. We all live in the company of the dead. What presence will we be for the lives that come after us?

To fix destruction is our task. What if that mandate summoned not delusions of escape and human grandeur, but repair? Restoring what has broken is a reminder to be careful with what is here now. It is an entreaty to make things last and to care for what will outlast our small tender lives. Not an easy task. It will take, I think, all of what I find inspiring in Karl Luks’s story: how he worked hard and collectively, how he believed justice was possible and equity critical. Our uneasy world needs his courage and his bodily sacrifice. But it also requires trading the temptation of apocalypse escapism for world-historical humility, for perseverance without certainty, for prophecies that hold space for more than people. We must make better ruins. My pros’ba, here on this river, is not for a new heaven and a new earth. It is for this earth: I wish to make mends that will hold us.

The sun is rolling toward its setting, late in this summer of intense heat. From inside the yaranga comes faint laughter, and then a yell that the meat is ready. I turn and take shelter among the bent alder rafters, snug under the canvas and reindeer skins.

- From the collection of the Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography (Kunstkamera), Russian Academy of Sciences, МАЭ И 1454-77

- From the collection of the Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography (Kunstkamera), Russian Academy of Sciences, МАЭ И 104-54

- From the collection of the Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography (Kunstkamera), Russian Academy of Sciences, МАЭ И 1454-228

- From the collection of the Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography (Kunstkamera), Russian Academy of Sciences, МАЭ И 1454-158

- From the collection of the Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography (Kunstkamera), Russian Academy of Sciences, МАЭ И 1454-100

The Dissolution

Environmental historian Bathsheba Demuth observes the spread of COVID-19 while researching the 1911 outbreak of smallpox among the Vuntut Gwitchin of the North Yukon and ponders waiting, isolation, and the dissolving partition between world and self.