Lauren E. Oakes is an environmental scientist and author who writes about forests, climate, and our complex relationships with nature. Her book In Search of the Canary Tree was one of Science Friday’s Best Science Books of 2018, the Second-Place Winner of the 2019 Rachel Carson Environment Book Award, and a finalist for the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine Communication Award. Her latest book is Treekeepers: The Race for a Forested Future. Lauren has contributed to The New York Times, The Los Angeles Times, National Geographic, Scientific American, Nautilus, and Anthropocene Magazine.

Kaisa Reese Ahluniq Kotch splits her time between Kotzebue and Sitka, where she is a senior at Mt. Edgecumbe High School. She is an active member of the Kotzebue community, helping others cope with mental health challenges and trauma. She volunteers frequently, singing for Iñupiat elders. In 2016, she was selected as Miss Teen Arctic Circle, and in 2017, she was the recipient of the Spirit of the Youth Lifesaver Award for the state of Alaska. Her mother is Maija Katak Lukin.

Maija Katak Lukin is the former mayor of the city of Kotzebue. She was a land manager in Northwest Alaska before recently starting a new position in tribal relations. When not working for the federal government, Maija is with her family, often gathering subsistence foods and teaching her grandchildren about their culture.

As she listens to three generations of an Iñupiat family in Kotzebue, Alaska, discuss the transformations and losses in their community that have resulted from climate change and COVID-19, Lauren Oakes reflects on the meeting place of scientific knowledge and Indigenous ways of knowing as a cornerstone of building resiliency.

The first time I corresponded with Maija Katak Lukin, she was about to leave town and head upriver for a hunt. “Moose season opens August 1st,” she wrote, and “because of the inconsistent migration of the caribou herds, moose is our only other choice for large land mammals.” In recent years, the start of the caribou migration and its duration have become more variable; so have the terrain covered by hundreds of thousands of hooves and the lives of the hunters pursuing the herd. The caribou move south from the flanks of the Brooks Range, often crossing the tundra later in the year than they have in the past, and unpredictably so. Fall and winter come later now, too. The ice, thin and slushy in places, melts and cracks and slips away earlier in the spring.

Born in Kotzebue, Alaska, and raised on the shores of Cape Krusenstern National Monument, Lukin is half Iñupiaq and half Finnish. She is the former mayor of the city of Kotzebue and was a federal land manager in Northwest Alaska before recently taking a new position in tribal relations. In 2015, when President Obama traveled to the Arctic to bear witness to the effects of climate change in the north, it was Maija who welcomed him to Kotzebue. Her brown eyes sparkled as she sat beside him, grinning wide. It was the same expression of joy and pride I’d seen in the many photos of her with her children and grandchildren, of her carrying baskets full of berries, hanging salmon to dry, sewing mukluks and sealskin mittens, embracing tradition and passing it on, too.

“Native people have been managing natural and cultural resources for at least thirteen thousand years,” she told me when we finally spoke on the phone. “You don’t have to be Indigenous to be a good leader. But it is important that you do live here, or you have lived here, and that you’re very, very open to listening.”

I wanted to talk with her about change—change driven by climate; change in community and culture triggered by a rapidly shifting environment; change in resource management in response to the warming world. I knew that climate change had already challenged the lifeways of the people of Kotzebue, but our crackly phone conversation unveiled another layer. Climate, along with COVID-19, is driving inequitable impacts.

I would have traveled there to speak with Maija and other community members in person; I wondered how such a relatively isolated community was finding resilience amid the many effects of climate change. But the pandemic kept me home in Montana. It had brought Maija’s children and other family members home, too.

“You should talk to Kaisa, my daughter,” Maija said. “She’s seventeen, and the changes she sees are normal for her. But they’re not normal for me. In my forty-three years of life, so much was the same until the last ten years. For my mom, so much was the same for some fifty years. The change that we’ve experienced over the past decade has created a notable insecurity around food gathering and food storage.” This is our warming world—where uncertainty reigns and survival depends on collaboration and innovation in the midst of many changing conditions. Some places and people have already been hit hard; some places and people are already adapting. There is more to come.

Through my knowledge of Western science—the startling climate projections and consequences—and Maija’s local knowledge of place, formed through culture and tradition, we each know loss. But perhaps, where our knowledge comes together, we can work toward greater resilience in a world coping with colliding crises.

The coast and melting ice in the early spring.

Kaisa this summer, on the shores of the Chukchi Sea.

The Iñupiaq name for Kotzebue is Qikiqtaġruk, which means “almost an island” or “small island”; and it is just that—a peninsula today and an island of the future. About thirty miles north of the Arctic Circle with a population of some 3,300 people, Kotzebue lies on a gravel spit at the end of the Baldwin Peninsula in Kotzebue Sound, part of the Chukchi Sea. No roads lead in or out. Rising seas seep inland. Three rivers—the Noatak, the Kobuk, and the Selawik—drain into the sound, making Kotzebue an historical hub for trading between villages and now also a transfer point between the ocean and inland shipping.

In 2012, the community erected a seawall. It cost about $40 million and was funded largely by the federal government, with the tribe and village corporation contributing as well. Scientists at conferences I attend often show aerial photographs of it as an iconic portrait of resistance to the warming world. Physically, that wall defends Kotzebue; it is a “resistance strategy” against what some scientists deem to be the inevitable fate of coastal inundation. But the people who have lived there for thousands of years, hunting seal and caribous, traveling by river, and crossing solid ice, are not merely resisting; they are part of a larger community in transformation.

Transformation is a term I know through Western science. It’s gaining traction today, but even scientists themselves have yet to define it precisely. Relationships in ecosystems are constantly changing (and always have been) through interactions between species and the physical environment, and climate, as well. In the dance between predator and prey, one population benefits while another declines, until the cycle reverses again. After a glacier retreats, a forest forms over time. The first plants fix nitrogen and enable soils to develop, creating a suitable home for the trees of tomorrow. Ecologists have long recognized that an ecosystem can function within relatively predictable bounds for long periods of time and then shift, abruptly, to something new. Nothing stays the same forever.

Add people to the “system” that a scientist studies, and transformation becomes both social and ecological, integrating people and nature (as they are, in fact, inseparable). Transformations have always occurred, but what makes them different today is the rate, scale, and driving force of climate change.

“We see lakes underlined with permafrost,” Kyle Joly, a wildlife biologist for Gates of the Arctic National Preserve, tells me. “The permafrost melts, and it acts like a bath with its drain pulled. The lake drains its water virtually instantaneously. It changes the ecological community from a freshwater one to a terrestrial one.” That’s an ecological transformation at a small scale. But when many small-scale changes occur over an extensive area, large-scale ecological transformation ensues. “We’re seeing forests browning in the Arctic; they become less productive. We’re seeing increasing permafrost temperatures that are leading to all sorts of changes, like collapses of riverbanks that add more sediment, impacting fisheries. We’re seeing more shrubs on the landscape, and they’re getting taller. They can create additional places for predators to hide.” Changes in the sea ice affect polar bear and walrus communities and the hunters who utilize them. Fish are showing up in new areas. Other species, like beaver, are spreading north. Transformation occurs once a tipping point is reached; the people of Kotzebue live in an ecosystem that has already crossed many thresholds.

I understand these changes ecologically, but I have more to learn about what they mean for people—for individual lives and also for thousands of years of tradition based on a knowledge system that never separated people and nature in the first place. Indigenous people have been coping with and adapting to changes—both slow and rapid—for millennia. Kamaksriłiq Nunam Inqtaɳanik means “respect for nature.” It is one of the core traditional values (Iñupiat Iļitqusiat) of the Iñupiat people. “No moose this trip,” Maija wrote me after her hunt. “We wait until they give themselves to us.” Take only what you need. Share with others. Work hard and cooperate. Care for one another. These are values held by a remote, Arctic community that I have never visited; a culture I am only starting to know.

The Iñupiat people carry generations of knowledge of ice conditions and caribou migrations, and equally fresh in their memory are the deaths from the 1918 flu that plagued many Arctic villages. Climate and COVID-19 are exposing the hidden vulnerabilities of communities like this one. But Kaisa, Maija’s daughter, and other residents of Kotzebue offer a glimpse of what resilience requires when change is both unfathomable and inevitable, when we must find ways to work together even as we are apart.

Kaisa and her mother in 2017.

Kaisa in 2016, when she was celebrated as Miss Teen Arctic Circle.

“Even if you leave,” Kaisa told me the first time we spoke, “you are always brought back. Kotzebue is home. There’s a lot of history here. It’s kind of like waves; they go out, but they always come back in.”

As a student at a Native boarding school in Sitka, a small town about 1,200 air miles away in Southeast Alaska, Kaisa has been coming and going for years. Amid the pandemic, she quarantined in Anchorage before returning to Kotzebue early in April, where she then quarantined again. Back home, she noted it was strangely warm and wet for that time of year.

“When I was younger, we used to go ice fishing with my brother and sister after their birthday, which is in late May. We would go out there on the ice and not have to worry about anything.” But by April this year, the ice that locks up the rivers had already broken free. The same had happened the year prior, too. “You can’t go ice fishing without ice.”

I wanted to understand the changes observed across generations even before the virus arrived: from what Kaisa described to me as one baseline, to another that Maija knows from long ago, and yet another that her mother remembers. I asked Kaisa if she would interview her mother and grandmother. I didn’t want to collect their stories from afar. I hoped, instead, for permission to listen in as they were passed among family, held first in their proper place in culture and community and then shared beyond together. I felt nervous asking, like an outsider stepping into a tradition of oral history that is deeply ingrained in the culture. But perhaps in asking and in sharing, we can begin to build trust and create new knowledge together.

There’s an article I recently read in the journal Science about the struggle to bridge scientific research and communities, about giving voice to Indigenous people in the study of warming and all its consequences. In it, anthropologist Dr. Julie Raymond-Yakoubian asserts that there’s a body of knowledge a community develops that cannot be replicated by Western science. It got me thinking: If we can improve our collective knowledge of the problems we’re facing by better integrating different perspectives and ways of knowing, then it only follows that the solutions come from the same collective wisdom.

What I know of climate change comes from research, my own experiences far from Kotzebue, and efforts to implement what scientists call “nature-based solutions”—actions to sustainably manage and use nature to address societal problems. What Kaisa and her family know comes from a long history of home and an enduring relationship with nature—one of mutual care. Like a fly on the wall—a distant wall—I listened to their stories in my makeshift basement office, the quiet space where I’d been working amid the stay-at-home orders. Barren walls surrounded me; one window offered a hindered view of the summer sky.

In a conversation between grandmother and granddaughter, I witnessed memories of seal meat and distant snow-covered tundra. There never used to be muskox, Kaisa’s aana, her grandmother, recalls of home. She is speaking of Ovibos moschatus—the thick-coated, hoofed Arctic mammal of the Bovidae family. “Now there’s muskox there [when] you go pick berries, and they’re all over.” It’s hot and buggy. The storms are more intense, too. “Hardly anybody uses dog teams to go places, and that was our main ride.” With deteriorating ice conditions, the Iñupiat hunt for seals earlier or sometimes not at all.

Take only what you need. Share with others. Work hard and cooperate. Care for one another. These are values held by a remote, Arctic community that I have never visited; a culture I am only starting to know.

Freshly picked lowbush cranberries (Vaccinium oxycoccos), kikminnaq in Iñupiaq.

There, in my basement, hearing the words shared between daughter and mother, I listened for glimpses of how one change triggers another. “Snow level dictates how much drinking water we have,” Maija says, “because it melts and it goes into the watershed, into the lake that we use for our drinking water source.” Snowpack is decreasing; it is possible they could run out of water. “We haven’t yet, but it’s come close.” Summers are warmer: no longer with highs in the 60s, like in Maija’s childhood; 70-degree temps are the new normal. Long and frigid winters are fading. “Ice safety is one of the things that’s concerning, not just personally but professionally as well. I’ve lost family members—not immediate family members, but, you know, cousins and uncles—because they are traveling at the time their dads and their grandparents and their ancestors traveled across the ice. But it’s not safe anymore. So, we’re having to relearn certain things like the thickness of ice by just looking at it.” Going upriver, there are more willows and alders and even some trees that weren’t there before. “When I was growing up,” she notes, “we had caribou and salmon and white fish and waterfowl and things like that. And we didn’t generally eat a lot of moose, just because there wasn’t a lot of moose around here.”

Kaisa asks her mother, “What are some traditional things that you did that you don’t see your kids or grandkids doing?”

“My kids will probably never hunt a seal on the ice. So you’ll never, probably, throw a harpoon, and you’ll never be able to do that.” She chokes back tears and quickly falls silent. There is a long pause, stillness in the grief for what was, the recognition of what is no longer.

“My kids and my grandkids will probably never hunt a seal on the ice,” she repeats. “Six hundred years of hunting seals is gonna stop with us or with you, because it’s not safe, and because it’s further out, and because we don’t have the ice that we used to have.”

She’s talking about a loss of tradition, yes, but also a loss of sustenance. Four apples in Kotzebue cost fifteen dollars today; a pound of pork is about the same. When goods come only by boat or plane, and intermittently at that; when weather still limits travel; when a virus, layered on top of climate change and relative isolation, further limits the movement of people and products—what happens next? And if food can’t be gathered directly from the land or the sea—then from where?”

Listen to an audio clip of Kaisa interviewing her mother and grandmother.

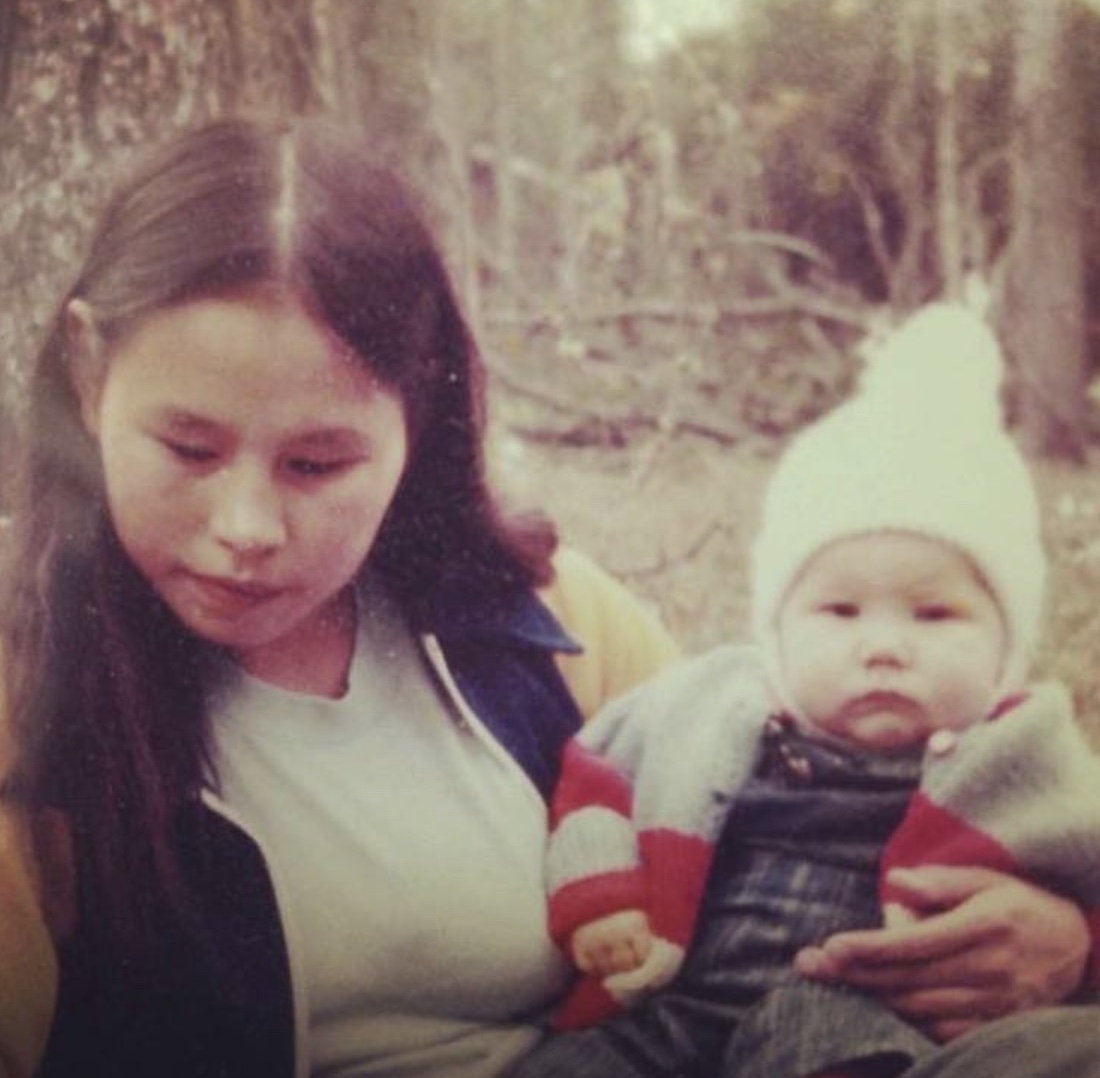

Photo: Maija as a baby with her mother, picking highbush cranberries in Chickaloon, Alaska, 1977.

Around the same time that Kaisa returned home from school, villages across the state filed a series of emergency action requests. Far from Kotzebue, two villages in the southeast archipelago asked for emergency authorization from the state and then the federal government to hunt earlier than the regulated season. Regulations on the number of animals that residents and non-residents can take and at what time of year are in place for good reasons: management strives to sustain wildlife populations and protect the mating season, too. In the statements filed by representatives of the villages, they noted that stores weren’t able to stock at the same level they’d maintained before the pandemic. The villages wanted approval to turn to the land, to embrace the self-sufficiency of their past and a security beyond what supply chains could offer. They wanted deer and moose—not many, but just enough.

In the vicinity of the expansive drainages of Kotzebue Sound, the Chukchi Sea, and the Arctic Ocean, where Kotzebue resides and residents roam, the request was different: to close public lands to users who are not federally qualified subsistence users for “reasons of public safety” due to the coronavirus pandemic. Residents cited concerns about outsiders—such as hunters flying in from Anchorage—bringing the virus from more populated cities in Alaska and beyond. The first person to test positive in Kotzebue arrived on a plane about a month later. Other cases followed.

“The conundrum we have,” Maija told me, “is that we’re operating federal public lands that are open to the general public. How do we do that safely for the residents, and then safely for the people coming in?” But there is also a history of friction between Alaska Natives and out-of-town hunters; charter flights bring in sport hunters every year who contribute to the economy but also add another challenge to the management of wildlife populations. Closing public lands to others is something that some residents want despite COVID-19; but doing this would also have ripple effects.

“If they close hunting to non-residents, my brother and cousin and aunt couldn’t come home and hunt,” Kaisa told me. “My dad is 100 percent white, but he’s spent thirty years perpetuating the culture. So, if we close hunting to non-Iñupiat people, then he wouldn’t be able to hunt. It’s confusing and complicated, and there are no easy answers.”

In a rapidly changing world plagued by a pandemic, it becomes all the more pressing to consider how wants compete with needs. Making sense of who gets what and how that is decided in Alaska requires going back to the early days of statehood. “Federally-qualified users,” I learned, means “rural,” the controversial and loosely-defined legal term that emerged as result of ANILCA, the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act, in 1980. Not long ago, Alaska was a 375-million-acre tabula rasa with respect to land designations—from a colonialist perspective, that is. In the process of making the vast territory a state, land and rights and Native claims were “settled.” But they were also stolen. The great challenge was to achieve equality for all while also giving subsistence preference to Native people—something which was attempted through the language of the acts that passed and the practices that followed. What governs today is a legacy of the past. What generations remember is also a loss of sovereignty.

One attorney who was heavily involved at that time explained, “a racially-determined program for Native preference wouldn’t fly”; it wasn’t in line with the Fourteenth Amendment. Native people wanted to use “Native preference,” but “rural” was used instead—a term with hopeful intention that could be applied to any people living off the road system who were challenged to meet their needs due to relative isolation and who were bound to the land through a long history of customary and traditional use. It became more inclusive, with “rural preference” applying to both Native and non-Native residents throughout Alaska, and this created tension between the state and federal government about who gets the last word with respect to the people, the land, and the animals. If there’s an inadequate harvest, an unmet need, or an issue of customary and traditional use, then anyone can step beyond the state and file an emergency request to the federal government for consideration.

The Federal Subsistence Board denied the request to close public lands for reasons of public safety. “The justification for your request,” the decision letter read, “states that closure of Unit 23 … is needed to minimize the spread of Coronavirus to ensure social distancing and curtail nonessential travel. Such a request falls outside the scope of the Board’s authority as it is an epidemiological issue.” The city of Kotzebue could suggest a quarantine and test on arrival, and it did. But a non-local or non-Native Alaskan from Anchorage, for example, or an Iñupiaq person returning to visit family, or a year-round resident of Kotzebue could all still hunt the caribou, too—that is, if the caribou, in their uncertain migration, passed through.

One village, Kake, which is also rural and predominantly Native, was granted the emergency right to harvest up to two antlered bull moose and five, male Sitka black-tailed deer per month over the summer. Elders were the first to receive meat from the approved hunt. But then the state filed a lawsuit, alleging a federal agency had overstepped its authority by opening a hunt for “alleged COVID-19” reasons. The outcome will undoubtedly reshape the rights of people living in remote communities, yet management may need to evolve with the rapidly changing world, too. When more voices and values inform decision-making, communities and management can better work together to meet basic needs (and deprioritize wants) in the midst of crisis; this kind of transformation in governance would include more sharing and more care for one another.

Avoid conflict. Respect others. Respect nature. Cooperate. Share. These are the values held by the Iñupiat people; they need to be embraced more widely.

What Kaisa and her family know comes from a long history of home and an enduring relationship with nature—one of mutual care.

Salmon hanging to dry before smoking and canning.

Storing smoked salmon for the year ahead.

An elder, Aana Beulah, as Kaisa calls her, cleaning a fishnet in Kotzebue. (“I have many aanas, grandmothers,” Kaisa explains. “They are all my grandmothers.”)

“So, can you tell me a little bit about the food security in Kotzebue prior to coronavirus? And how has coronavirus changed things?” Kaisa asked her aana in the recorded conversation she passed to me.

“What do you mean by food security?” her aana replied. Listening to the audio of their conversation, I imagined her grandmother had never needed such a term. Stresses on food supply would have been lived and felt, motivating concern and action, connection to the land and the sea, and to other people, too.

“Now that the virus is here, people are starting to do a lot more hunting, a lot more putting their food away,” she said. “They’re starting to grow more and preserve more of the subsistence foods.”

Maija calls such preparations her salmon math. She calculates her needs for the year ahead based on a diet of salmon four times a week. She picks berries every day to amass thirty gallons for the winter. Sausage will come from moose or caribou—however many she and her husband can get. Chickens in the backyard offer reliable eggs.

“If you’re an Alaska Native,” she told me in August, “you’re meal planning for the whole year right now.” Because of a way of life, yes. Because of tradition, yes. But also because of climate change. Because of management and rights and access and supply chains. Because a mixed cash-subsistence economy means there are only so many hours in the day to work for money and then to gather and hunt for food. Because of uncertainty—so many uncertainties: the movement of caribou, the movement of people, the arrivals of planes carrying goods and more. Because of the virus.

Adaptation for the people of Kotzebue today also looks different than it has in the past. Long ago, Iñupiat people turned to the sea when hunts on land were less successful. Trade between villages provided another support in challenging times. Now, adaptation also includes more gardening and increasing cash flow to purchase gas and store-bought goods. In the warming world, questions linger about the subsistence activities that remain essential to survival: Do we support decisions that favor short-term food security? Or work toward sustaining wildlife populations, which may be affected by future climate, too? What shifts in our actions and our relationships to one another can ensure sustenance into the future?

Being a good leader, as Maija says, requires listening to others. It may also require integrating different forms of knowledge across cultures and communities, and helping people work together to cope and generate solutions. I know that science alone cannot resolve the climate crisis, nor the pandemic; massive problems require coordinated action, born within communities and shared across cultures. Perhaps the immediate step is to redefine “we”: to be more inclusive when it comes to decision-making; to consider a broader range of values; to empower more individual and collective action.

In one of the recordings Kaisa gave me, she tests the microphone before interviewing her mother. She sings a song in English. There is a calmness in her tone, an ease that is absent from her conversations about change. Maija had told me that over the summer Kaisa would stand outside the homes of elders and sing to them in their isolation. I wondered if this was one of the songs she had sung to them, but Kaisa told me that when she sings for elders, she tends to sing in Iñupiaq. “I try to use as much Iñupiaq as possible, because you can see in their faces how it warms their hearts to hear a younger generation speaking the language that was taken away from them.” There are new leaders rising; may their voices be heard.

Kaisa’s niece and Maija’s granddaughter, Charlotte, in Kotzebue this past winter.

Additional financial support for research contributing to this story came from the National Climate Adaptation Science Center in association with the project, Adaptation Strategies in the Face of Climate-Driven Ecological Transformation. Regional assistance was also provided by the Wildlife Conservation Society’s Arctic Beringia Program.