Melanie Challenger researches and writes on environmental history, bioethics, and philosophy of science. Her books include How to Be Animal: What It Means to Be Human; Animal Dignity: Philosophical Reflections on Nonhuman Existence; and On Extinction: How We Became Estranged from Nature, which received Santa Barbara Library’s Green Award for environmental writing. She has written for several publications, including New Scientist, The Guardian, Aeon, Nautilus, and BBC Science Focus, and has participated in documentaries and film for the BBC, CBC, Arte, and ZDF. Melanie serves as deputy chair of the Nuffield Council on Bioethics and a vice president of the RSPCA. She was part of a team who drafted the first Declaration on Animal Dignity in 2024 and is a founding member of Animals in the Room, a project that seeks to expand democratic imaginations to explore how animals can be present, participate, and be represented in the decisions that affect them. In 2025, she became a National Geographic Explorer.

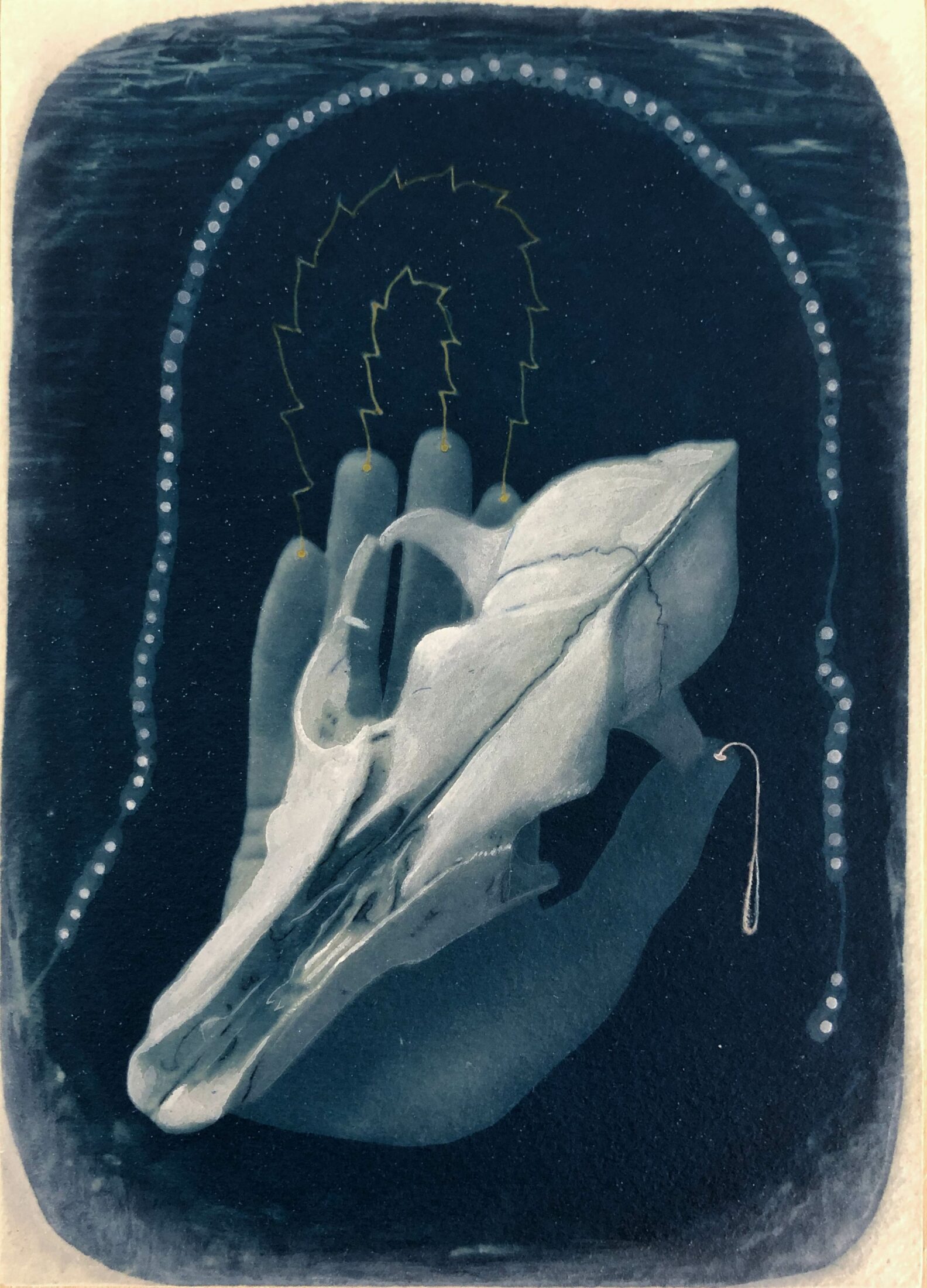

Annalise Neil lives and works in San Diego, California. In 2006, she received a BFA in printmaking from the College of Saint Rose in Albany, New York. Annalise has exhibited her work at juried shows throughout the United States over the last fifteen years. Her work resides in public and private collections across the US and in Europe.

As Melanie Challenger examines the belief in human exceptionalism that has devastated life on this planet, she wonders if our desire to outrun death is hindering our capacity to love.

I: Meeting Death

I met Death in my early twenties. I had already lost loved ones before this time. A friend at school was taken by leukemia in a breathtaking six weeks one strange, hot summer. My grandfather, Eric, and my uncle, Tim, both died before their time.

But none of us truly meets Death until we are ready to understand what it means. My first meeting came while sitting in a recording studio with a Holocaust survivor called Hannah.1 Hannah had endured the death march from her home in Hungary when she was fifteen years old. In 1944, she and her family were transported by cattle truck to Auschwitz. Out of dozens of family members, only she and her brother came through the war alive.

We were doing interviews together for radio stations around the country on Holocaust Memorial Day. As the interviewers asked us questions, we both did our best to respond. Hannah was a practiced educator and skilled at relating what was necessary of her trauma. And what she said on air was harrowing. Yet Hannah was willing to share only so much among strangers. As one interview came to an end, we returned to the muffled silence of the room. And in this silence she began, softly, to expand on her testimony. What she had to say, uncensored, was more vile, more brutal, and desperately sad. Her expression of the potential for staggering cruelty in our species spun a pall of death over me. I could not cry for her because she did not cry. I could not hold her because she did not look me in the eye. But I didn’t leave that room the same person. I have never repeated what she said to me. It isn’t my story to tell. But the mark of her trust has never lifted. She humbled me in every sense.

Among the many lessons Hannah taught me that day, and in the days to come, was the significance and seriousness of grief in human lives—which is another way of saying the significance of love in our lives, because it is the fever of our attachment to one another that charges grief with its intolerable brilliancy. And so, my meeting with Death that day was as much a meeting with Love.

But my second meeting with Death didn’t come for many years, despite the illnesses of my mother and father. Instead, the meeting happened a little after my eldest son’s tenth birthday. Landmarks in parenting often creep up unannounced. Hence, I wasn’t aware I had been thinking about his passage into a new decade. Or the physical changes that begin to show like an early spring around the body of a child who is in the anteroom to puberty. Yet one evening while I sat on my bed reading quietly, long after the children were both asleep, tears began to flow. It was like the fable of the crow and the pitcher. It felt as if some unseen weights had been steadily dropped into my body and finally the waters of grief were rising up and spilling out.

It is a quiet kind of grief that a parent feels as each stage ends. And difficult to articulate. Yet we know it when it arrives because some hidden part of us recognizes that new teaching skills must now be called on. The old tools we used with a younger child must be put away. And with that comes the knowledge that something irrecoverable and precious has ended, and so too the deeper knowledge that our children are themselves irrecoverable and will, unavoidably, one day be gone forever. That is an excruciating kind of realization that is also the espousal of both Love and Death.

What my meetings with Death taught me is that humans are profoundly affected by the one thing that all of us, no matter our fortunes, have in common with the rest of life: we will one day die. Everything that we have cherished, each hope or triumph, however small or glorious, will be gone. And so, too, will the unique form of our bodies. Our smiles and the cut of our buttocks, our hips and the hue of our eyes—all will one day be swallowed back into the immensity of the cosmos.

Of course, all organisms strive to survive. They exchange energy and DNA in their efforts to persist not only in their lifetime but also into future generations. And all species have strategies to delay death and avoid injury. Some other species experience something akin to grief too. Ethologist Marc Bekoff has assessed the evidence from a range of findings, especially among mammals. In one study by Shifra Goldenberg on the death of an elephant matriarch, a complex of reactions emerged, even among the unrelated elephants.

“What the family was doing was interesting, but what her non-relatives were doing was also important,” Goldenberg noted. “You see their investigation of the body. You see calves walking past and smelling it. It is amazing to see that level of fascination. Her family was distressed that she wasn’t getting up. But the larger population also was interested in her death.”

Wolves have been recorded returning to the bodies of dead group members and howling over them. Chimpanzees and other primates have consistently been found to carry their dead young, sometimes for weeks, despite showing signs that they understand the infant is not alive. The psychology of death among chimpanzees, our closest living relatives, is a compelling pointer to the origins and qualities of our own psychology.

Yet among humans, whose complex memories muddle together meaning and death in highly evocative ways, such sensitivity, distress, and adaptive avoidance can become a waking fear. All the grieving animals mentioned here are social animals. Perhaps it shouldn’t surprise us, then, that we are affected in this amplified way because we are such breathtakingly, indiscriminately social beings. We are the consequence of our species’ so-called cognitive niche, the outcome of our fierce entanglement with one another. Over countless generations of our animal becoming, we have traded our minds with one another—negotiating, sharing, arguing, investing in our young, cheating one another, exploiting, and cooperating—and out of that crucible of social relations has emerged a primate with a strong knowledge of both self and others. We also possess a set of memory systems that fizz with prediction and recollection. With that acute knowledge and memory comes the indiscriminate anticipation of death.

Yet the same group pressures that crafted our minds have also provided the possibility of our salvation. Because thousands of years of evolution within groups have gifted us with the idea of the group—whether that’s our tribe, our nation, or our species. And that latter idea, in particular, remains a source of both solace and salvation. Because it’s the very notion of our humanity as both singular and triumphal that has given our lives their ultimate meaning and security. The only trouble is that it’s a devastating idea for the rest of the living world.

II: Denying Death

In 1973, the year before his own death, American anthropologist Ernest Becker published his masterpiece, The Denial of Death. In it, he sets out his thesis that the progress of humanity is a hero quest, a conceptual search for the meaning that will save us from the terror of death and the futility of life.

“It doesn’t matter whether the cultural hero-system is frankly magical, religious, and primitive or secular, scientific, and civilized,” he wrote. “It is still a mythical hero-system in which people serve in order to earn a feeling of primary value, of cosmic specialness, of ultimate usefulness to creation, of unshakable meaning. They earn this feeling by carving out a place in nature, by building an edifice that reflects human value.… The hope and belief is that the things that man creates in society are of lasting worth and meaning, that they outlive or outshine death and decay, that man and his products count.”

Becker’s insights gave rise to a vibrant branch of psychology, spearheaded by psychologists Jeff Greenberg, Sheldon Solomon, and Tom Pyszczynski, called terror management theory. According to the theory, we soften our mortal fears through cultural beliefs that offer us a kind of immortality, such as the concept of the afterlife or the salvatory tech ideas of transhumanism. Hundreds of studies from around the world have attempted to capture this “fear management” in action, most often by exposing participants to something that reminds them they are mortal and then tracking how this affects their behavior. Many of the studies have pointed to a common impulse to reinforce our sense of belonging to a group, and sometimes a temporary preference for forms of exceptionalism, whether that is human exceptionalism or stronger beliefs in the superiority of one’s group.

My meeting with Death that day was as much a meeting with Love.

The theory was later refined to incorporate the idea that any reminders of our mortality, including our physical reality, our biology, and our animality, can be viewed as threats that we ritually manage or shun. A particularly fascinating line of research has looked at the ways societies respond to the female body, as both the vessel of life and a stark reminder of our animality and, by association, our mortality. That has included studies that suggest that contemplating death can make us more averse to breastfeeding, for example.

I came across this work through my own hunches about the ways we process threats and buffer ourselves through group ideologies and intuitions about our nature. It had always fascinated me that most cultures around the world see humans as having a spiritual and an animal part. Across time and cultures, it has been incredibly rare for people to think of humans as simply organic beings. Even atheist beliefs often espouse the idea that there’s some human quintessence that somehow elevates us above the rest of nature, even if this is only viewed as a possession of our lifetimes rather than a condition of the post-life state.

This means that most people alive both now and in the past have believed that life—or, more particularly, human life—is made up of two parts: the physical and the transcendent. In philosophy, we call this “substance dualism.” In Indigenous worldviews, all living things are understood to share in this transcendent essence. But many years of theological discussion within the cultures of early monotheism eventually gave rise to the idea that only humans possess this second, essential substance. In other words, only humans have a soul that will come to the rescue.

Later still, following on from the ideas of Enlightenment philosophers like John Locke and Immanuel Kant, humanists and atheists dispensed with the fuzzy notion of the soul. A new argument emerged that the special substance that defines our humanity is our rational minds. It is our cognitive capacities—our personhood, our free will, our reason—that mark out and validate our existence as a species.

This, it seemed to me, has all flowed from certain assumptions about ourselves. Our extraordinary subjective consciousness gives us the impression that we are somehow carried around by our bodies, that we humans peer out from within an animal skin. And with that comes the powerful sense that this human, ratiocinating part of us is the meaningful aspect of our existence, while the physical, animal half doesn’t really matter. We can see that intuition mirrored in our philosophical ideas. Most of our major industrial civilizations are structured around the belief that the human spiritual or thinking part is the source of our true moral value. And unlike our hunter-gatherer siblings, many modern thinkers are now convinced that only humans have any truly spiritual or personal substance within them, so it follows that only humans mean something and warrant moral concern. In other words, we are protected against the worst of our cruelties, whereas other species can be exploited, killed, and their homes destroyed, because they are mere bodies, but we are beings.

Unsurprisingly, this belief system is toxic to the rest of life on our planet. If it’s only the human essence that truly matters, then it doesn’t matter that we—this special thinking animal—are killing and endangering the evolutionary pathways of hundreds of thousands of other species on our planet. Because if we tell ourselves that only our special human essence has value, then only we truly matter on this Earth. And by this logic, as long as we pursue human needs, we are doing good in the world, regardless of any wider destructive consequences. That is one hell of a bias.

Today our major societies continue to justify our damaging impacts on Earth and other life forms on this basis. When interrogated, however, the idea of human exceptionalism can be extraordinarily difficult to ground in reality. That is because, at its heart, it is a belief rather than a fact. It is a belief about the value and quality of humanity. It is a belief that human uniqueness allows us both to endure and to triumph. It is the idea to which we default when confronted by human activities that seem to run counter to our moral high ground. The most common form this idea takes is the argument that humans have a special kind of intelligence from which full moral worth and duties follow. But other common forms of exceptionalism rely on the soul or personhood or the idea of “dignity.” We rarely allow ourselves to consider how odd these moral convictions are. But when we dig into them, we soon realize we will have to meet with Death to truly understand them.

All of this turns on our hypersociality and its legacies. Humans are group-living animals because this way of life has given us a survival edge. Life on our planet is a daily miracle of order, a balancing act of elements and energy that, under different conditions, would fall apart and disperse. The physics of it all is staggering enough. But then individual organisms are faced with continual threats to their integrity and survival. Staying alive and well can be a hugely stressful prospect. Dangers and tribulations result in biochemical responses that help the animal overcome a danger but must be paid for through wear and tear on the body. Consequently, all animals also seek to mitigate the effects of stress.

We aren’t immune to the repercussions of danger, no matter how savvy we are. When we face a threat, including the idea that we will die, our bodies enter a stress state. If we remain in that state, it will have a negative effect on our long-term well-being. One major solution to danger is avoidance. But as social animals, we’ve also evolved to manage the effects of stress through our bonds with one another. When we face a tough time or are frightened, we seek out one another, and this lowers our cortisol level, our heart rate, and our respiratory rate, thus reducing the damaging effects that stress can have on the body. Often this is purely physical and unconscious, as in cuddling closely with a loved one, which allows us to regain our equilibrium. And we’re not alone in this. All social animals behave in this way, from horses to prairie voles. These effects are well studied in nature as “social buffering.”

Yet humans are fascinating in that we do a similar thing with our ideas too. We cling to our group and reinforce our group identity when we’re stressed, and that can include the big conceptual group called “humanity.” But what do we do if this idea of “humanity” buffers us from our fears about the human condition and leaves all other life forms on Earth outside of our moral circle? That is a rather lonely solution.

Enough of us are so determined to outrun Death, pursuing our security and dominance, that modern civilization has become as big a dealer of deaths as an ice age. In our consumption of the bodies of other animals and our destruction of their homes, we have become our own geological era—and often, it seems, as callous and unthinking as a physical force. But is this inevitable? How can we escape a cycle in which we look out on nature, fear the realities we see, arm ourselves with a false narrative of our own superiority, and, in so doing, hobble our moral agency?

III: Embracing Death

Each day, my children and I walk the nine-thousand-acre forest where we live. It is an allegory of mortality, a dripping, creaking landscape of decay and renewal. Recently, while the boys and I were out walking, we came across a dead rabbit, concave as a plastic bag in the rain, its organs and viscera gone. It lay in the shape of its running as if something had turned it two-dimensional. We stood in silence and stared at it. A few days before, we’d found a dead shrew, its tiny, penitent hands held out, like a toddler asking to be carried. This is the way of the forest.

And a forest smacks of reality—more reality than our species has been comfortable with for thousands of years. At night, this forest sings with death. It is home to goshawks and tawny owls, little more than burning eye and claw and intention. It is home to foxes and adders, who wait for the dark and the tang of life on the breeze. It is home to huge mycelial networks that pulse with consumption and exchange, and whose dusty children mark the deaths of trees.

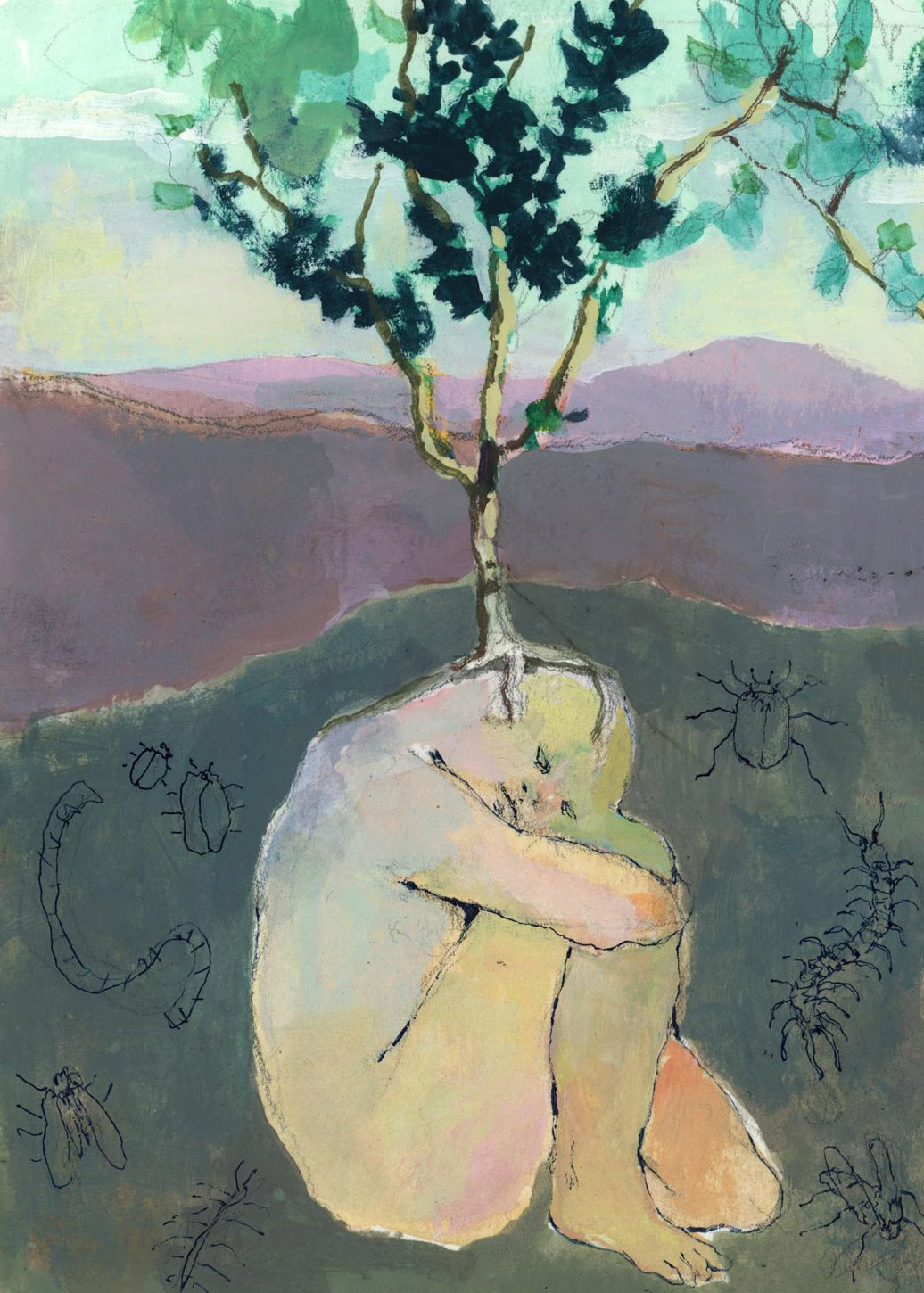

In our current dominant value system, we convince ourselves that there is a gulf of meaning between the lives of these woodland animals and us. They pass an existence of impoverished being. They have no sense of meaning, and so they mean nothing. Or so the story goes. As Martin Heidegger once claimed, they must perish. Only we humans have enough being to “die.” Death has no such prejudices. Death—whether we call it dying or perishing—is coming for all of us. For all life on Earth. For the Earth. And, one day, for the conditions that have made an Earth possible in the first place. This is the reality that hums beneath us, whether we acknowledge it or not. Regardless of what we achieve in our lifetimes, regardless of whether we hide our corpses away in boxes and erect tombstones, the matter of us will decay, and its energies will release again and find their way into the body of another organism or the fabric of another object in our world. We are all part of the circular economy of life on Earth for as long as the conditions will allow.

But would it assist us to recognize this? We humans love so long and so darned hard—including kinds of self-love—that accepting an absolute death can seem intolerable. What if we revive our sense of meaning without recourse to substance dualism? What if we find inspiration and reassurance, instead, in the idea of a kind of substance process, an exchange of one state of form and order for another?

The majority of us continue to hold faith in our spiritual beliefs. And a growing minority also uphold the dream of transforming their cognitive lives into zeroes and ones and sending their minds off on an eternal journey into the Great Unknown of the cosmos. It needn’t dim the hope for God to recognize that none of us knows what heaven might be. As for space—it isn’t a vacuum or a heaven. And how easily we can forget that machines are made of materials too. Even machines die. But perhaps it’s neither here nor there how we think about death. Perhaps the work that must be done is in how we think about life.

For all our destructiveness, humans are also promiscuously compassionate and thoughtful. In fact, humans are what I like to call “love generalizers.” Our bodies reservice hormones like oxytocin from our maternal-child bonds in our later affiliations with one another—and also when we bond across the species boundary. It is a marvel of nature that a creature like us has evolved in such a way as to be able to love a skink or a pig or a python or a wren. Okay, perhaps we don’t love these other species quite as forcefully as we do our own kind (our love for one another is incredible). But we can love completely unrelated members of our species. And, yes, perhaps we don’t love them quite as much as we do our children, but we are still extraordinarily promiscuous with our affections. We are a strange marriage of possible loves, an infinity knot of infinite possible relations. And we don’t tell ourselves this anywhere near enough. The generalizable nature of our affiliative biology is our real superpower. So perhaps we might place a little more faith in our bodies.

And perhaps we might use that superpower to create better relationships with the other species around us. If we made a bigger group, a group like “life on Earth,” we might engender more morally robust relationships with other species around us while simultaneously buffering ourselves a little from all we fear of our reality. We might form a better relationship with the finiteness of life. A better relationship with the truths of our condition. When we are closer to the animals and plants that accompany us in this life, we share in their demise and in their aim to flourish, which raises the force of their deaths and softens the force of our own. Death and Love, after all, are the same thing.

- Her name has been changed for privacy.