Erik Jacobs is an award-winning photographer, whose clients include: Time Magazine, Newsweek Magazine, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The International Herald Tribune, Travel and Leisure Magazine, and many more. He has taught photography and storytelling at Boston University’s Center for Digital Imaging Arts.

Dina Rudick is a documentary filmmaker with deep roots in journalism and a passion for telling critical and complex stories. She has won four Emmy Awards for her video and documentary work, as well as dozens of national photography awards during her decades-long career as a staff photographer at the Boston Globe. Dina taught photography and video for years at Boston University College of Communication and Harvard University Extension, and she is currently the owner and director of Anthem Multimedia, a video production company in Boston that specializes in short-form cinematic documentary work.

Erik Jacobs wrestles with opposing notions of purpose: his dream of tending a thriving farm and the urban reality of his small, fenced-in yard. But as he recovers from cancer during the pandemic, he comes to inhabit a new vision of home.

This was never The Dream.

Not this house. Not this town. There’s another place: twenty-five acres of fertile fields and forest, with a pond and a stream. There’s a barn there, full of history and swallows, a Jersey cow for milk, chickens and goats, and endless space where my kids can run, barefoot and free. There, days are a Divine Office attuned to the rhythm of the seasons and demands of place. A patch of land where I can control the chaos of the world and insulate my family from its future. A home where I care for the earth and am fed in return, body and soul. And eventually, when my time comes, I will lie down, wrap the soil blankets around me, and finally rest. I’ve seen it all so clearly.

It’s called Someday Farm, and it exists only in my imagination. You see, I’m a farmer. Or, at least, I was until recently. But I live in a city, surrounded by a rusty chain link fence, atop subprime soil laden with broken glass and lead. Here, under constant noise from airplanes and a starless sky, I’m awash in the frenetic hustle of my species—drinking, speeding, littering, and stealing right outside my windows. I escape to Someday Farm whenever I start feeling too naked and vulnerable—too dependent on and too complicit in the rapacious systems I want nothing to do with. And just as rain lands on the ubiquitous concrete around here, I, too, rush to touch the living, breathing earth again. My source, my center.

I’ve been searching for Someday Farm for eight years. I hunt through listings up and down the Connecticut River Valley, hoping to find the right combination of price, agricultural character, and proximity to the city. We’ve visited more properties than I can count. We’ve fallen in love—twice. But each time we got close, something wouldn’t fit and the vision would collapse. We’d recalibrate to our life back at the gray house in the city, mourn, and then resume the search. But the problem was, I never unpacked. I just lived out of my boxes, knowing that soon I’d get the chance to truly settle in. Two words preceded so many of my thoughts: “If only… ”

Spoiler alert: we’re still here. As I write this, I’m staring at a mosaic of vinyl siding and power lines. There’s the occasional car, a few dog walkers in masks. It’s quiet now, partly because the world is in hiding. But the quiet also comes from something else. Something that’s been here all along, just hidden by leaf blowers and my hot pursuit of possibility. It’s something that approaches peace, though it’s hard to separate from being close to death.

I began to notice it two years ago. My heart was beating unusually hard, and things were not adding up. Not the forty-five-minute commute to farm some rented land, not the relentless call of my city job as a photographer and the demands of two young kids at home. The economic reality of farming was too daunting, and my physical limitations too apparent. And then I noticed a strange lump in my neck. I was concerned, but never truly believed in my mortality. I went to the doctor, mostly as an afterthought, and returned home with a diagnosis: head and neck cancer.

To survive, I would need six weeks of radiation, two planned surgeries, and one emergency surgery to stanch a vessel hemorrhaging blood into my throat. I was repeatedly wheeled into operating rooms with hand-drawn notes taped to my gown: “Please take good care of my daddy.” My main job was to keep my weight up to avoid a feeding tube. But I wasn’t hungry, ever. I lost my sense of taste and developed deep ulcers on my tongue. Swallowing three thousand calories a day sent waves of fire searing through my head. I ate as if I were lifting weights: each thirty-two-ounce smoothie required five sets of ten chugs. Four weeks into radiation, I caught the flu. And then pneumonia.

But I didn’t suffer alone. With a lot of love and support, I emerged on the other side without a feeding tube. The deep scars on my neck would heal. The irradiated cells in my throat knew how to shed and regrow.

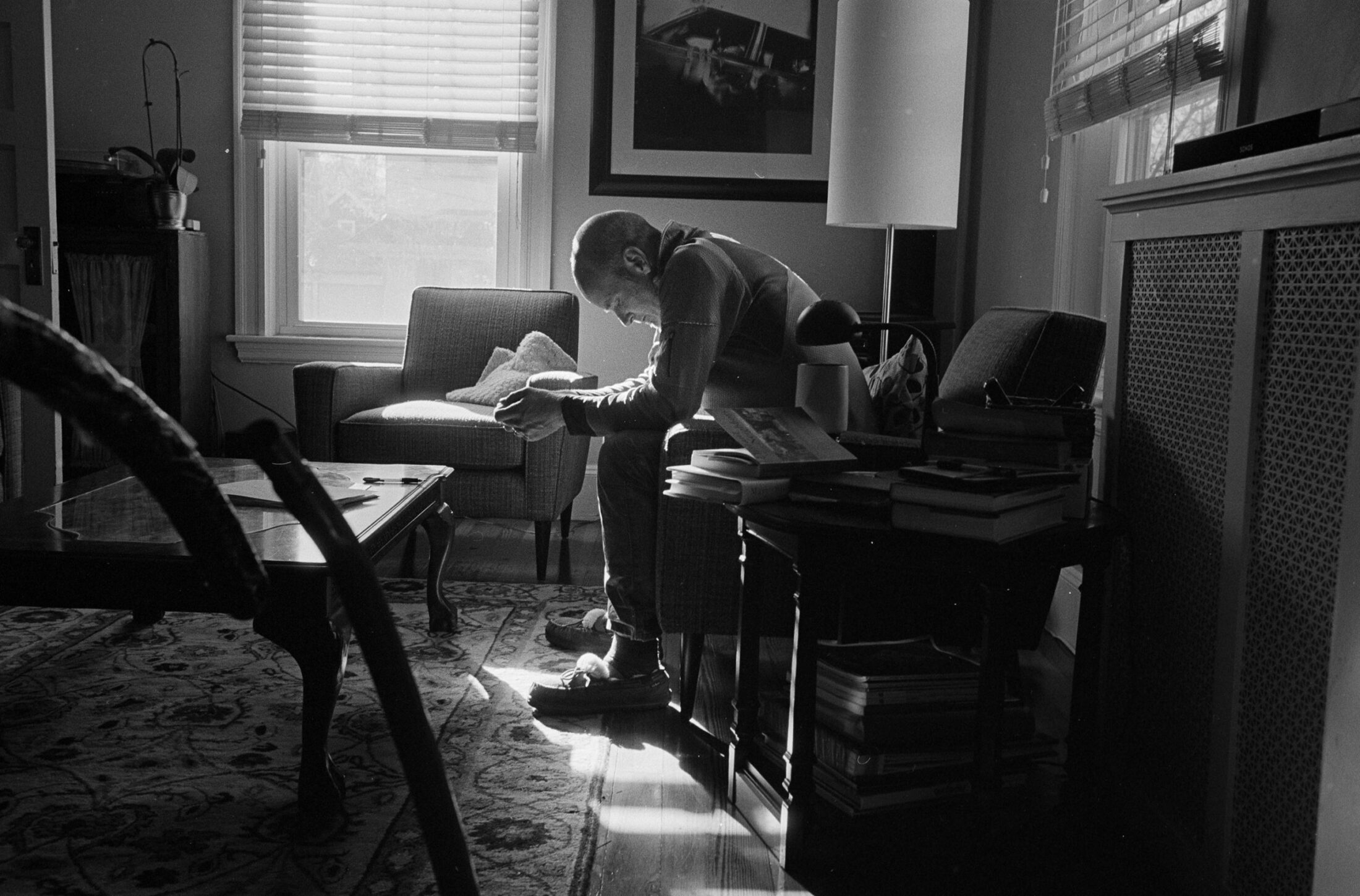

My new job—and what turns out to be the harder one—was to come to terms with my new body. One that looks normal but can’t swallow the same way. One that feels infinitely more fragile. And to learn how to live my life with an all-too-present awareness that it could go away at any moment.

I live in this liminal space—stuck somewhere between here and whatever’s coming next. The truth of this transient existence isn’t new. But now the end point is less of an abstraction. In the dark silence of the night, I often lie awake, jolted by a twinge in my neck, and I spiral down from there. The cancer is back, I’m sure of it. I sketch out my final letters and then give up on sleep, drag myself out of bed, and drive to a lake deep in the woods, seeking something big and eternal to quiet my mind. When I arrive, it takes a moment for the brightness of my fear and the man-made world to fade. If I sit still for long enough, eyes closed, ears open, I begin to disappear into the sound of rain falling softly on the surface of the water or wind twisting the branches above. When I open my eyes, I’m prepared to return home and try again.

If living through cancer has been anything, it’s been a process of learning to let go. Or, at least, of holding things more loosely. Sickness forced me to release my grip on many things that shored me up: my able body, my work, the feeling of certainty and control. Life since then has been a daily practice of shedding these layers and trying to come to terms with a future without me at its center. Many days, it feels more like tearing than graceful surrender. And the tearing is worst when I loosen my grip on one bond that’s too painful to imagine breaking.

“’Tend dat” is the way my four-year-old daughter, Auden, pronounces “pretend that…” when she is feeling particularly like Pegasus or a dragon. Before I got sick, “’tend dat” was an exhausting game that took every ounce of my best dad energy. I was more enchanted by my list of things to do and the unwritten emails awaiting my return. But as I emerged from treatment and started to regain my strength, my supporting role in “’tend dat” was bliss. Oscar-worthy. I earned the moniker “Nice Giant.”

“Auden,” I would begin in my gruff giant voice, “’tend dat we are invincible and nothing can hurt us, no matter what.”

I relished anew being tumbled up with my kids’ healthy, pink bodies and being immersed in the worlds playing out invisibly before our eyes. The expansive universe would shrink to the safety of our home, our yard. There was nowhere else I wanted to be.

Now hard times are pressing in again. The dangerous world I feared most—the one I had sought an exemption from by farming my way out—is at our doors: coronavirus. And I’m still here, in the wrong zip code. I beat myself up. Maybe we should have pulled up stakes, costs and compromises be damned? We could better feed and quarantine ourselves on a farm. But I don’t trust that instinct as much. A sense of control is not something I can claim these days.

So we wait. The prognosis is certain: the months of fear and suffering ahead will be hard. I dread the impending suffering, but I cling to what I’ve learned from this familiar place—that even when tomorrow is no sure thing, when bodies fail, when dreams recede, when the world shrinks to the four walls around us, there is still something expansive that blooms in darkness. That “something” may feel far from hopeful at this moment. But it is there. Even and especially in the months ahead. Out of our deepest brokenness, we can be remade.

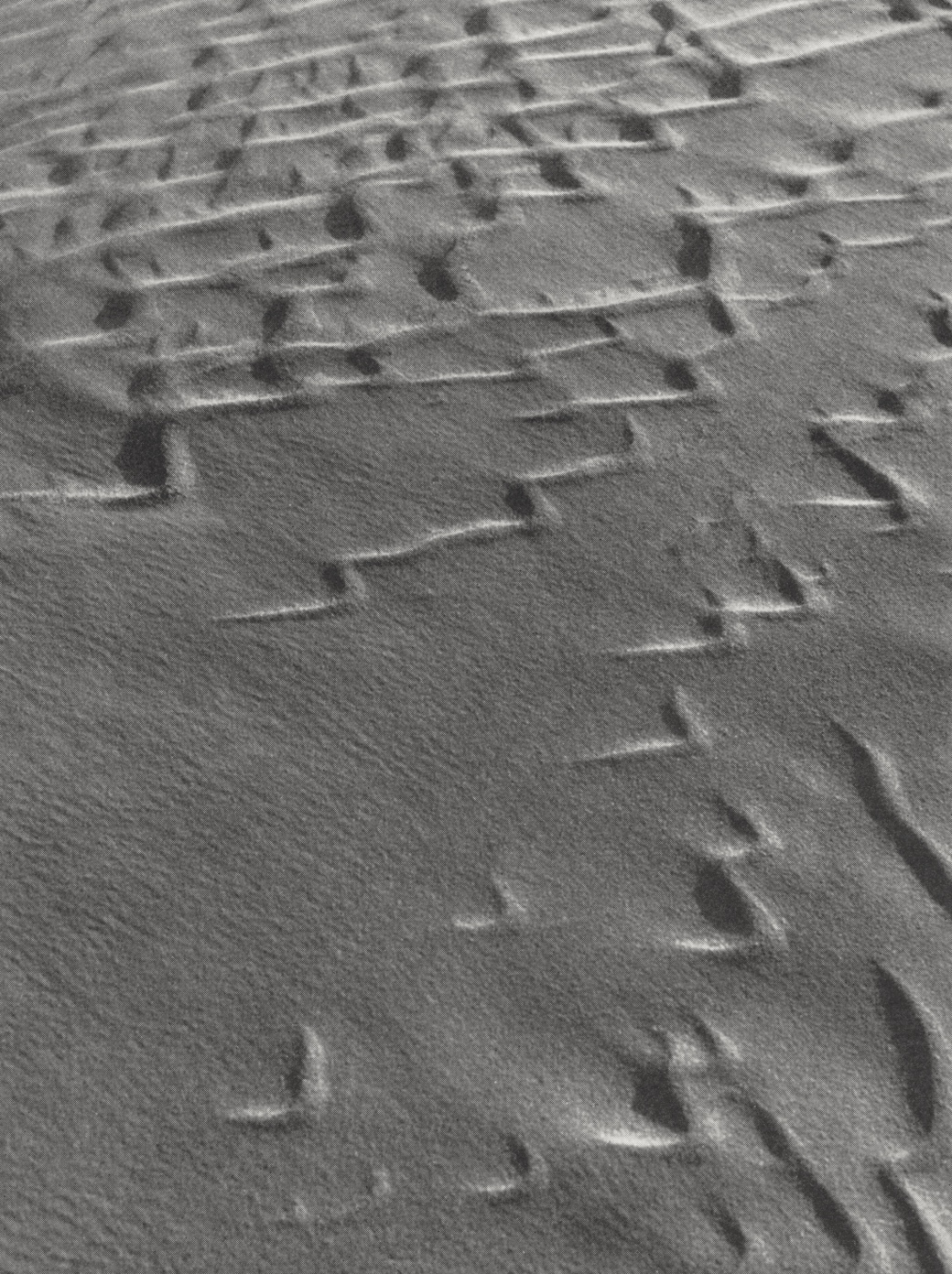

Ever since we gave up the rented two-acre plot we were farming, all of my nervous energy has been flowing out into our tiny yard—the only land we’ve got. Under three towering Norway spruces, I’ve inoculated logs with shiitake spores. Concord grapes drape a narrow alley next to the garage. Our kids pick freely from cherry tomatoes, snap peas, and black raspberries in the southwest corner, which we call the “snack yard.”

This land could keep us fed for a day—two, tops. Our cars are broken into regularly. No matter how many soil tests I’ve done, I don’t fully trust that what we’re eating isn’t laced with something toxic. This was not The Dream. But that narrative lives mostly in my mind. Our kids think it’s magic.

My fixation on our Someday Farm, to the exclusion of what lay before me, feels like a virtuous cousin of the flaw that endangers our species: the tendency to desire and consume anything and everything, simply because we can. The trait that keeps us hungry and searching, even though we’re already fed. I had tasted the sweetness of life lived close to the earth, and I wanted more: more land, more years to tend it, more unobstructed sunsets—a deeper well of connection. I still want that. But what’s been illuminating in sickness and this pandemic is how much of that deep well I can touch right here, if I can shut out the world of what’s infinitely possible and instead focus on the infinity that lies between me and the horizon.

Loving the natural world where it interfaces with the human requires more work. Beauties are more subtle, distractions are many. But connection is here. The same cycles of life and death play out and remind us that we’re briefly in between. As I watch my family at play, in love, with the sun and the berries and each other, making elaborate funeral pyres for baby robins that didn’t fledge, I’m struck by what’s plain to see: this is it. It’s turtles all the way down. I’m reminded that our Earth has been doing the living and dying thing for a long time, and I don’t need to feel so scared. Nor do I need to run.

Fear and death have been a prism, shattering my existence into a spectrum of truths previously unseen. These photos are an attempt by my partner and I to show what we have seen, heard, and felt from the confines of our yard during this pandemic. Our aim is to capture a bit of the struggle and to reveal the splendor present in its midst. Through sustained attention and with sufficient grace, we’ve found an infinity of wonder right where we stand. The Dream now is simply to be still in its presence with what time we have. And to steward these miraculous gifts well enough so that they can sustain our kids when I can no longer.