Martin Shaw is a writer, artist, teacher, and mythologist. His books include: Smoke Hole, Courting the Wild Twin, Wolf Milk: Chthonic Memory in the Deep Wild, The Night Wages, and A Branch from the Lightning Tree. Shaw’s translations of Celtic folklore and poetry (with Tony Hoagland) have been published in Poetry International, The Mississippi Review, Poetry Magazine, Orion, and Kenyon Review. He is the founder of the Westcountry School of Myth, a learning community located on Dartmoor in the far west of the United Kingdom.

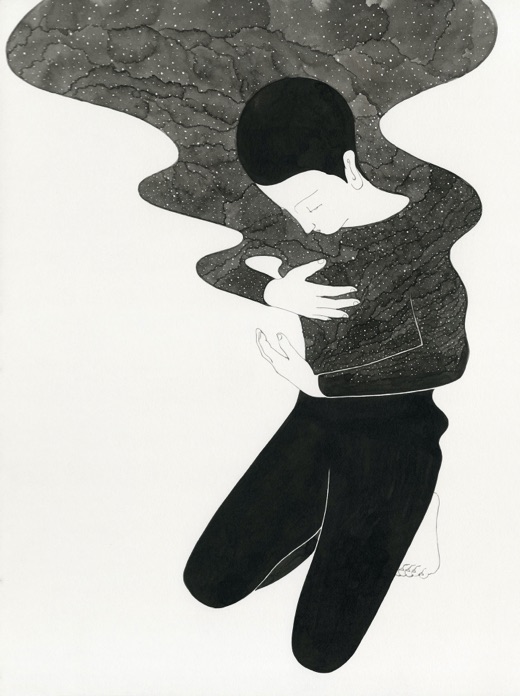

moonassi is an artist from Seoul, Korea, whose black-and-white drawings explore emotion, inner dialogue, and the human psyche. His work has appeared in The New York Times, Migrant Journal, and elsewhere, and has been exhibited in Seoul, New York, and London.

As we walk our questions into a troubled future, storyteller and mythologist Martin Shaw invites us to subvert today’s voices of certainty and do the hard work of opening to mystery.

The correct response to uncertainty is mythmaking. It always was. Not punditry, allegory, or mandate, but mythmaking. The creation of stories. We are tuned to do so, right down to our bones. The bewilderment, vivacity, and downright slog of life requires it. And such emerging art forms are not to cure or even resolve uncertainty but to deepen into it. There’s no solving uncertainty. Mythmaking is an imaginative labor not a frantic attempt to shift the mood to steadier ground. There isn’t any.

But—a major but—maybe there’s useful and un-useful uncertainty. The un-useful is the skittish, fatiguing dimension. The surface of the condition. The useful is the invitation to depth that myth always offers. Because if there’s uncertainty, then we are no longer sure quite what’s the right way to behave. And there’s potential in that, an openness to new forms. We are susceptible to what I call sacred transgression. Not straight-up theft but a recalibrating of taboo to further the making of culture. Let me give you an example of what I mean.

In a Hebridean story I call Cinderbiter, a serpent is wrapped four times around the world. Its head is a few miles offshore from a Scottish island. The only way to appease it has been to supply the creature with sacrifices. To satisfy a killer with killings, goes the stressed-out daytime logic. But this cannot continue, the island is running out of victims. The exhausted islanders are all out of ideas. Sequestered in the drama rests a boy who lies by a fire dreaming. Hearing of the many attempts to meet this peril, the lad uses night intelligence, not day, to save the island.

He steals three things.

- He steals his father’s speediest horse.

- He steals three embers from an old crone’s fire.

- He steals the king’s boat and strangely allows himself to be tipped into the belly of the beast. He then locates the liver. He cuts the liver open and places the crone’s embers inside. The serpent then ejects the boy and dies flamboyantly. As he collapses, his teeth become the Faroe, Shetland, and Orkney Islands, and his liver becomes the still smoking island we call Iceland.

Cinderbiter’s unconventional instincts save the day. His transgressions, forged in his dreaming state, have a genius that the islanders can only gawp at. And we swiftly move from a story of insurmountable dread to a creation story: the formation of the Scottish Islands and Iceland. It’s a refreshing narrative and only possible with openness to unexpected approaches. The warriors have been dealing with the outside of the situation, but Cinderbiter navigates it from the inside.

So when we face uncertainty, we should be open to the quixotic and the unconventional. Culturally we need to be Cinderbiters at a moment like this. It’s the Cinderbiter in us that would query the word “uncertainty” anyway. So, let’s re-imagine it.

Navigating mystery humbles us, reminds us with every step that we don’t know everything, are not, in fact, the masters of all.

What if we reframed “living with uncertainty” to “navigating mystery”? There’s more energy in that phrase. The hum of imaginative voltage. And is our life not a mystery school, a seat of earthy instruction?

There are few tales worth remembering that don’t have uncertainty woven into them. Without uncertainty we have mission statements not myth. We have polemic not poetry, sign not symbol. There’s no depth when we are already floating above true human experience. And true human experience has always involved ambiguity, paradox, and eventually the need for sheer pluck. Uncertainty doesn’t feel sexy, I admit. It can derail confidence, make us neurotic, doubt ourselves. But mythic intelligence suggests we have to negotiate such terrain for a story of worth to surround us. I don’t say this lightly; it has real testing attached.

The Handless Maiden, alone in the dark forest—she knows uncertainty. Odysseus, trying to get back to Ithaca—he knows uncertainty. The Firebird caged by a Russian Tzar—she knows uncertainty. Uncertainty is a jittery passport to the kingdom of the living, inevitable for all. Having lived half a century in its energy field, I make no pretense to like it much. But understand it? See its value? I do.

But to navigate mystery is not the same thing as living with uncertainty. It doesn’t contain the hallmarks of manic overconfidence or gnawing anxiety. It’s the blue feather in the magpie’s tale. Hard to glimpse without attention. There’s no franchise or hashtag attached. Navigating mystery humbles us, reminds us with every step that we don’t know everything, are not, in fact, the masters of all.

As humans we’ve long been forged on the anvil of the mysteries: Why are we here? Why do we die? What is love? We are tuned like a cello to vibrate with such questions. What is entirely new is the amount of information we are receiving from all over the planet. So we don’t just receive stress on a localized, human level, we mainline it from a huge, abstract, conceptual perspective. Perpetual availability to both creates a nervous wreck.

The old stories say, enough; that one day we have to walk our questions, our yearnings, our longings. We have to set out into those mysteries, even with the uncertainty. Especially with the uncertainty. Make it magnificent. We take the adventure. Not naively but knowing this is what a grown-up does. We embark. Let your children see you do it. Set sail, take the wing, commit to the stomp. Evoke a playful boldness that makes even angels swoon. There’s likely something tremendous waiting.

This is not to imply it’s easy. To become a warrior of the elite class in ancient Ireland you had to learn how to dance on the tip of a spear, to become a sovereign you had two wild horses attached to your chariot, setting out in different directions. Your task was to create, between the warring directives of each, a third movement, forged from the tension of both wills. If you could thrive under that discord, stay upright in the unknowing, make play from the tension, then you had the capacity to be a sovereign. And it wasn’t just a case of bullying the horses but making a kind of alchemical covenant between the two: you rode the counterweight and something new was birthed. That requires patience and a certain amount of discomfort.

So what could that look like in our lives? It means rescuing little ideas that gleam for a second in our soul then disappear. Coaxing them back. It means attention to not this or that but possibly both or some other way entirely. This isn’t necessarily easy, being so conditioned as we are to yes or no, black or white. And sometimes that third position is not what many would call a logical response.

The German Luftwaffe pilot Joseph Beuys became a critically important artist in the sixties and beyond. Lacerated with slivers of shrapnel, he was a mystical grief symbol for a country desperately struggling with the recent horror of its Luciferic legacy. His sustained encounter with the Otherworld of war bent his head in a new shape. I don’t say that to glorify warfare but to acknowledge that something was fermented in the most awful of conditions. A potent, ritualized personality.

When he was invited to exhibit in New York, he was wrapped in felt and driven to the gallery in an ambulance. Waiting for him inside was a coyote, and only a coyote. For several days the two of them circled each other until Beuys felt some energetic contact had been made. He then gathered himself, was wrapped back in the felt, and was driven away in the ambulance to return to Germany. He called the work I Like America and America Likes Me. Through his mythmaking, Beuys worked towards a new kind of conversation.

That seems an effective and magic endeavor to me. It feeds the underneath in us, the ceremonialist in us; it nourishes places in us that are secretive and fond of beauty. Work like this has been so undervalued and marginalized we can barely glimpse its implications, but our feeling-nature is energized by hearing of it. For me to unpack it further would be to neuter it, so I won’t do that. But I would suggest we allow fifteen minutes a day (preferably at twilight) to give ourselves time to brood on a personal matter as if it were Beuys doing the brooding. What would Beuys do? is an enjoyable question.

About two years ago, following a persistent hunch, I visited a local forest for 101 days, primarily to listen. An extended vigil. I sat by a hazel bush in the rain and the coming dark and did little. I would offer a gift then quieten down and try and catch the mood of the day. It proved to be the most exacting, even eviscerating, of experiences. Externally, it was a time in my life when I was being asked to speak frequently about the moment we were in. I had ambivalence about that. It felt like the slow slide into punditry, and so I did the opposite. I realized I didn’t need more time rattling around with humans, but I needed to simply be very quiet and pay attention. I look back at my notes now, and I read this:

America—lie back in bear fur

Russia—lie back in bear fur

China—lie back in bear fur

We as a people(s) need to lie back in bear fur.

Let us imbibe Bear’s wintering fat.

That would be a communion

Jesus would understand.

This little fumble of words is how I feel about things. Siberian myth says that to become a true human you must hibernate with a bear, suck bear fat from the center of its paw, give birth to babies with the ears of a bear. All sounds good to me.

I haven’t got a damn thing to say about living on Mars with Elon Musk. The essential ingredients of mythmaking are down here on our tangly planet, species whispering and muttering about each other. Really good gossip across species becomes a story and eventually a myth. So what are the stories that will come from the mysteries of our present moment?

I have become more eccentric since my time in the forest, clearer and occasionally kinder. Life doesn’t feel certain, but it feels succulent. Life doesn’t feel assured, but it feels vivacious.

It doesn’t feel safe, but it feels pregnant with possibility. And, like every human before me, I’m going to have to make my peace with that arrangement. To repeat, it was always like this.

As you will be understanding, I am trying to address the Cinderbiter in you. I’m not crafting a pamphlet, more a provocation, something to get you lighting a lantern to your own den of nighttime thoughts and wayward illuminations. I’m going to suggest four areas in which work could be done.

Move from seeing to beholding: To see a situation is to catch the facts of the matter. To behold it is to witness the story. If you dwell entirely with statistics and data, you will be a burnt match within months. Move from just seeing the world to beholding the world. Seeing is assessment and analysis; beholding is wonder and curiosity. It’s not that we don’t need the former, but when we crank it up excessively, we always damage the latter. Make space for the miraculous, make space for grace—these energies show up constantly in our lives. To behold them is to bear witness to them. To celebrate them. That’s an infectious and noble position to take. Difficult situations require sustained beholding. They are not necessarily to be dissected or defeated but sat with. Could there be a third way that arises from fidelity of attention?

Making a covenant with honesty: Take agency of the life that forged you. I’ve written before that we all have a prayer mat we kneel on, though many of us forget to look down. Stop glancing around and comparing yourself to others; instead gaze pointedly down at your mat. Catch its scent. Your mat constitutes everything that has grown you up to this point, especially the good stuff. There is a troubling spiritual idea that you actually elected to be born into the family you showed up in, the town you were raised in. There comes a point where it is childish to choreograph our personal history anymore. Tell it straight.

Make a covenant with honesty. Honesty is often a case-by-case disclosure. Orientate to what feels like truth. Endless fictions fatigue us. Be your naturalness, then commit to the lively disciplines such naturalness is calling forth in you. When you are trying to be honest in your loves, your dealings, your fundamental ground, you begin to become authentically yourself. Be accountable. This is absolutely the best position to navigate the mysteries from. Over time one mystery reveals itself, and then delightfully another opens.

When you are dishonest, you break connection with your soul. Something essential is weakened. Lying reduces your wingspan. Stay honest to the shape you came here to embody. Refuse to be a hologram or engage in acts of ventriloquism.

If your life feels peculiar, flamboyant, occasionally shameful, then those are the markings of that emerging authenticity. The more you settle back into your naturalness, the less likely you are to be endlessly buffeted by unease and unseated by paradox. If you are steady in your own precarious character, you recognize these energies as fundamental to the business of both living and deepening. Such honesty will also introduce both limit and consequence into your life. It creates a code, a kind of gallantry. Not from the outside, but from a daily, sometimes troubling, discourse with your own soul.

This kind of work creates a root system that is clear and well watered. Eventually it could create an old-growth human being. Let’s stop devouring for a second and take stock of the innumerable benefits we have already received. This begins by lowering our gaze to what’s beneath us.

Reaching out to nature and history: The notion of community is a breathless affair when we imagine it as solely human. At present I have two very interesting teachers: one is the hazel bush I sheltered beside during the 101 days, the other is the painter Ken Kiff. Ken is dead and a hazel bush is a plant, but that doesn’t stop me having a daily and invigorating dialogue with both. If life is uncertain, then let’s make that work for us. Let’s get expansive.

Maybe our soul does live for the most part outside of our body, maybe it drifts between centuries, is in love with the strident yellowed curve of a bullhorn from archaic Crete, maybe enamored with tapestries hung in the courtly schools of Eleanor of Aquitaine. Don’t brush your tastes away. Take your delight seriously. You could reach out towards historical figures, cloud formations, and badger tracks in the snow. Claim them as familial instructors. They have a kind of warmth attached. These are useful, odd ideas. Uncertainty requires such expansiveness, requires some flex, some curiosity.

Earning your name: The Greeks had the notion of Kleos—which means something like “imperishable glory.” This isn’t quite what I’m getting at. That’s the Achilles end of the spectrum. What I’m referring to is not as obviously heroic, but possibly deeper. We earn our name by what we bring back from the Underworld. If we have no gift, no insight, then we are often gabbling trauma rather than speaking wisdom. But without the weathering of uncertainty, and of underworld testing, we may not quite trust the returning initiate. Who becomes a good sailor without knowledge of storms?

As the Irish stories insist, to become a leader you have to have swum through swamps with a dagger in your teeth. You have to have become acquainted with pressure and not buckled but bent. No pressure no diamond.

The Underworld is the place where you broke bread with Baba Yaga, made peace with limit, were fed small scraps of meat by crows when you needed it the most. It’s the deep dip in a myth, the katabasis, the descent, the mischievous, startling bewilderment of irrational energies. Logic has little traction at such a moment. Successful returnees of the Underworld are Blake, Anna Swir, Patti Smith, Elie Wiesel. Sometimes we make these journeys alone, sometimes as a culture.

My petition is that we accept the challenge of uncertainty. As a matter of personal style. It’s the right thing to do. It’s what the Anglo-Saxons called “living in the bone-house.” We get older, we find life is riven with weirdness. We should be weird too. To know, tell, and create stories is a wonderous skill that keeps faith with the traditional and beauteous techniques our ancestors used when faced with the sudden mists and tripwires of living.

I want to finish with one last provocation. In the last eighteen months I have not told many stories out loud. This was an enormous change after two decades of doing little but telling tales. When I finally was roused to start again, I found I had a situation. The stories had fled. The stories had hurt feelings. When you tell a story several hundred times, at some point it generally starts to proceed across your imagining in a relatively stable manner. That’s not to say the story gets repetitive, but it is a dependable, snorting little Dartmoor pony, getting you from one side of the tale to the other. The apples you feed it are your daily fidelity to giving it voice. It trusts you. But when the stories lie dormant for more than a month or two, they slip away over the hill of memory and are gone. They often require an elaborate and concerted courtship to return.

What this means for me is starting over with the stories. I have to re-vision them, publicly, all over again; I have to grope furtively into my imagination till I brush the curls of the stories’ salt-stiffened fur; I have to stumble and leap and generally make myself exceedingly vulnerable. But for an authentic encounter, this is the only way. I’m not interested in what worked as a storyteller two years ago, only what is being disclosed now. Not all stories will be returning, and some in a new shape. I don’t know what will happen next.

So as I approach the mystery of telling these stories again, the uncertainty of working into my mythmaking, I wonder if we could do something similar with our own narratives. What are we bored by, what needs to stay buried? What deserves to be re-imagined, re-seeded, re-beheld?

That’s where the joyful work is. I’m handing you a spade.

This is a moment of unexpected possibility.