Diane Wilson is a writer, speaker, editor, and Executive Director of the Native American Food Sovereignty Alliance. She is the author of the novel The Seed Keeper; the memoir Spirit Car: Journey to a Dakota Past, winner of the 2006 Minnesota Book Award; and the nonfiction book Beloved Child: A Dakota Way of Life, winner of the 2012 Barbara Sudler Award from History Colorado. She is the recipient of a 2013 Bush Foundation Fellowship, a 50 Over 50 Award from Pollen/Midwest, and many other awards. Diane is a Mdewakanton descendant, enrolled on the Rosebud Reservation, and lives in Shafer, Minnesota.

Jesse Zhang is a Brooklyn-based illustrator whose work often features surreal figures and landscapes with touches of mystery and whimsy. She works in watercolor, ink, and digital mediums. Her clients include Adobe, The Believer, Illustoria Magazine, NPR, and The New Yorker.

Endeavoring to restore balance between the native and invasive plants around her home, Diane Wilson makes a relationship with the most aggressive species, asking: what does it mean to be a good relative to the land?

A long, gravel driveway leads to the ten acres in east-central Minnesota that I call home, winding past tree-lined hills, marshy areas that host peeper frogs in spring, and ending with a glimpse of a majestic tamarack bog. Migrating birds follow the nearby St. Croix River flyway and often visit our feeders. A pileated woodpecker calls from the tamaracks, a jungle cry piercing the quiet that surrounds this land—a place of serene, wild beauty.

Over the past sixteen years, I have come to know another side of this beloved place. Beneath its lush serenity, I see disturbed land slowly losing its mature trees, displaced by rampant perennials. When I first moved here, an ancient, perfectly formed bur oak, a remnant of the original oak savanna, dominated the land near the road. A year ago, on a calm, clear night, the oak’s mighty branches simply dropped away from its massive trunk with a crack that I heard from the house. On a sloping hill near this broken tree, chest-high prickly ash shrubs have grown from a small cluster to a nearly impenetrable, shirt-ripping, skin-tearing, thorny thicket that is slowly consuming every open space.

As a guest on this land, I feel a responsibility to care for these plants and trees, yet I am unsure how to undo past harms. When I first moved here from the cities (St. Paul–Minneapolis), I didn’t realize that I would need to unlearn what I knew about gardening. My first summer, I planted seventy-five white pine, spruce, and plum seedlings that were immediately devoured by deer. I planted gardens that were overrun by rabbits, voles, and quack grass. Slowly, slowly, I began to step back and pay attention to this new, raw world around me.

In my work with Native organizations that support restoring Indigenous food systems, I advocate for returning to a relationship with the land that is rooted in respect and reciprocity. Reclaiming this relationship requires balance between species to ensure the survival of all; it is a balance that has been threatened by the invasion of prickly ash. There is no Native word for “weed,” I have said to groups, sharing the teaching of a local elder, Hope Flanagan. Plants are medicine, food, or utility, all providing a useful purpose.

Here on this land, I struggle to apply this understanding about the worthy purpose of each plant to the harsh reality that has been unfolding before me. The farmer who previously owned this acreage considered these modest, rolling hills unsuitable for crops but useful for grazing cattle. In a short time, cows and wandering deer cleared the land of beneficial seedlings, the oaks and white birch that would have grown up to replace aging trees. Nature’s diversity has been replaced by the unfettered dominance of a few aggressive species. Enter prickly ash, a native plant with ambition.

Known as the toothache tree, this tenacious plant is spread through berries eaten by birds as well as by weblike roots that send up vigorous suckers, responding to the neglectful gardener with a rabbitlike enthusiasm for reproduction. Once recommended for its ability to quickly establish ground cover, prickly ash is at least holding soil in place as it advances steadily across every open field. After many years of half-hearted efforts at control, the hill near the dead oak tree is a bunker from which I have been outsmarted, outmaneuvered, and essentially banished. The path I used to follow to leave prayers at the oak tree is now closed to me.

As a result, I have come to regard prickly ash with an intense feeling akin to loathing. Even though I understood that every plant has teachings and gifts that might be shared with the patient observer, and that its presence on this land was no coincidence, I was a reluctant student with a bad attitude. The plant reminded me of my shortcomings, the disconnect between the words I speak and my inability to achieve balance in my own backyard.

As the old trees have given way—often surrounded by prickly ash and buckthorn—the land has come to mirror the loss of identity that has affected generations of Native families, including my own. My mother and aunts grew up in South Dakota boarding schools run by Jesuit priests where Native language and spirituality was forbidden. Other assimilation policies, including land allotment and reservations, were invested with a darker subtext of separating Native people from the land, from the water, from our food. To me, the prickly ash hill was the equivalent of unbridled colonization forces at work, creating a new narrative that has displaced this land’s original story. And yet, this metaphor could not explain the natural laws of this place that I would need to learn in order to be of any real use.

As the Dakota historian David Larson once said, “When you know what was taken away, then you can reclaim it.” His words gave me a place to begin.

Focusing first on controlling the prickly ash, I consulted the internet, that vast oracle of plant knowledge. Experts generally recommended removing the shrubs and spraying the stumps with an herbicide such as Roundup to prevent regrowth. I also read: raindrops in the Midwest now contain glyphosate, a key ingredient in Roundup.

Other experts, who opposed the use of chemicals, suggested cutting the slender trunks in late spring when the plant was at its lowest ebb, and recutting until it was subdued enough to reintroduce other native species. In the book Wilding: Returning Nature to Our Farm, a couple successfully restored native plants to a conventional farm with severely depleted soil. The introduction stated, “Lately the news about our relationship with nature has been grim and apocalyptic.”

Elsewhere I read: One million plant and animal species are now at risk of extinction. This includes the monarch butterfly.

Had I followed the advice of these well-intentioned gardeners, I might have written a detailed account of my reclamation of prickly ash hill, of storming the bunker with my lopper and restoring the land to its pregrazed nature. An epic tale of gardener as hero.

This is not that essay. As a Dakota grandmother, I have a responsibility to reach for a deeper understanding. I refuse to accept a relationship with nature that is grim and apocalyptic. The challenges on my land and these expert answers come from a Western mindset that sees the land as a commodity, as natural capital. For the sake of my grandchildren, I need to relearn how to listen for the silenced voices of my ancestors, for the plants and land to speak.

Lacking any easy answers, I am left, instead, with questions. What has been taken away? What does it mean to be a good relative to this land? To prickly ash?

To me, the prickly ash hill was the equivalent of unbridled colonization forces at work, creating a new narrative that has displaced this land’s original story.

Like any good quest, this one begins with a story. Ever mindful of Thomas King’s illuminating book The Truth About Stories: A Native Narrative, I knew that in order to understand this place where I lived, I would need to know its story.

Two miles from my home, the slow-moving St. Croix River makes its way toward the Mississippi. The Dakota name for this river, Hogan Owanka Kin, translates to “where the fish lies,” referring to a legend about a hunter who was transformed into a giant fish that, in turn, became a sandbar where boats were occasionally stranded. This place is wakan, or sacred, for the Dakota.

When I paddled my kayak here in past summers, I was traveling a well-known trade route that Dakota people have used for thousands of years. As my ancestors paddled their canoes on this river, they, too, might have seen a bald eagle land in the upper branches of a cottonwood tree. Campsites along the forested banks were used by tribes who came from the north to trade copper from Lake Superior and red pipestone from northern Wisconsin with tribes living farther south. They must have shared feasts while visiting, trading medicinal and food plants, swapping seeds of corn, beans, and squash grown in small plots on river floodplains.

Before settlers arrived, vast maple and oak forests grew along the river, while tamarack swamps formed in depressions left by ancient glaciers. A bit farther south, glaciers formed shallow lakes where wild rice grew in such abundance that the lakes were said to resemble a green meadow. The rice fed thousands of wild ducks and geese as they migrated through the area. For Native people, this land provided a seasonal grocery store. In turn, they helped maintain the balance between species, between relatives, by using only what was needed and intervening with great care.

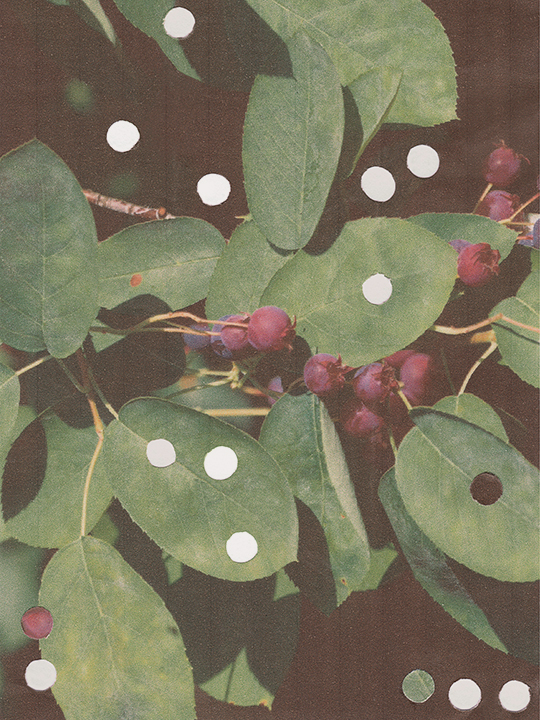

Prickly ash may have been present even then, its voracious appetite for land held in check by the robust diversity of the surrounding forests. As the story goes, Native people used its numbing effect to cure toothache and joint pain, and its citrus-scented fruits offered a distinct flavor when used in cooking. The leaves are toxic for most animal species, but the giant swallowtail caterpillars depend on it for survival.

Today, little remains of the original native plants and animals who once flourished here. The wild rice beds disappeared around 1900, when their waters were muddied by farm field erosion and chemical runoff. Ducks and geese became less abundant as the wild rice diminished, deer were hunted intensely, and surrounding oak forests were consumed by a nearby charcoal factory. Much of the remaining vegetation was cleared for cropland, and drainage ditches were constructed through the marshes.

Given this story, it’s a miracle that several acres of tamarack bog remain untouched on my land. These tall, deciduous evergreens are the reason I moved here from the cities, having lived with a lone tamarack in my small yard for many years. Each season, I watch as their soft needles transform from edible shoots in spring to lush green foliage that turns a deep gold before revealing bare, snow-lined branches in winter. A watery moat surrounds the tamaracks, crossed mostly by whitetail deer who leave sure-footed trails through this porous, unpredictable landscape. The moat also protects the tamaracks from the gradual invasion of prickly ash that has taken another hill, that one in dangerous proximity to the bog.

And therein lies the reason for my toxic anger toward prickly ash; left unchecked, it threatens even this rare habitat, one of our few remaining connections to the land my ancestors knew and cherished. When I look beyond my anger, I discover a deep well of grief for the suffering of my ancestors and the loss of knowledge that they carried.

In the spring of 1863, several large boats came north up the Mississippi carrying a load of escaped slaves, who were released near Fort Snelling. The empty boats were then reloaded with Dakota prisoners who had been captured or surrendered after the 1862 U.S.-Dakota War, and the last strip of Dakota homeland along the Minnesota River was seized by the government. The prisoners, a group of about 1,600 malnourished women, children, and elders, were shipped down the Mississippi to St. Louis, and then north again to Crow Creek, a hastily prepared, barren reservation in South Dakota. As nature abhors a vacuum, settlers moved swiftly to fill the newly emptied Dakota homeland in Minnesota.

Among the causes of the Dakota War are loss of ancestral land, disappearance of wild game, extermination of the bison, crop failure, food locked in a warehouse, stolen eggs, starving children. Skin color.

The Dakota left behind bark lodges, tipis, tools, weapons, food caches, ancestral graves, memories, abundant water, horses, a familiar horizon, birch trees and evergreen forests, wild rice beds, seasonal knowledge of plants, rivers. Their dead, unburied.

The Dakota brought with them the clothes they wore and what they were allowed to carry. Prayer. Seeds sewn in the hems of skirts and hidden in pockets. The children who survived.

The Dakota homeland received fences, titles, a price tag, chemicals, monocultures, reservations, invasive species, genetically modified seeds. False promises to feed the world.

For the sake of my grandchildren, I need to relearn how to listen for the silenced voices of my ancestors, for the plants and land to speak.

In the dream I was sitting in the kitchen of my childhood home, in the same chair where my mother used to sit at the table. I was talking on the phone when four white men wearing fake yellow uniforms, like employees of a home service business, burst into the kitchen from the room where they had been hiding. I was shocked and scared, knowing they had come to hurt me. Still holding the phone, I spoke calmly to the leader, as if I weren’t afraid. But when he revealed his violent intentions, my terror woke me.

Later that same day, I was working in my converted garage studio, still unnerved by the dream. My window faces north toward a tiny seed garden where I was growing a dozen stalks of Dakota corn, an old variety that had survived the removal to Crow Creek, and a handful of Hopi black turtle beans. A family of garter snakes lived nearby, helping to protect the corn by eating voles and other pests. Next to my garden grew a nasty tangle of vines, scrubby grass, buckthorn, and prickly ash that was barely held back with a metal fence. It was a perfect September afternoon; quiet, peaceful.

A large truck roared up the hilly driveway, shattering the calm. Four men wearing neon yellow vests climbed out of the truck and began unloading chain saws, a brush mower, a Bobcat, and a tall extending lift. The young man in charge was friendly, respectful, his eyes hidden behind dark sunglasses. A letter had arrived months earlier informing us that the trees and shrubs on our land that grew beneath the telephone wires had to be cleared to provide access for future utility work. As homeowners, we had the option to take on this maintenance ourselves. In past years, the lopping and trimming had seemed relatively benign, so I had not responded to the letter.

I negotiated with the young leader as the crew continued to unload equipment. Most of the trees and shrubs they wanted to cut were volunteers planted by birds dropping seeds from their perch on the wires. Our compromise: they could clear the buckthorn and prickly ash if they left the red cedar and trimmed only the white pine.

For the next several hours, machines roared and hacked all around my studio. Even with the windows closed against the noise, I could hear the bite of metal teeth on soft wood. I was unable to focus on my work, too distracted by their movements past my window. By their yellow vests.

When they were finally done, their leader knocked on my studio door. The four men stood together as a group, sweaty, smiling as if pleased with their work. The young man told me the tangle of vines and prickly ash near my seed garden was cleared. “If you plant a garden there, we won’t have to maintain that area,” he said.

After they left, I stood in the newly cleared space, horrified by the carnage they had left behind. The overgrown vines, Virginia creeper, prickly ash, buckthorn, and weedy grass had been brutally removed, the plants shredded into a thick layer of mulch. A large swath, at least fifteen feet wide, had been clear-cut from my garden to the road, leaving an ugly, naked strip of plant stubble. The sharp, tangy scent of prickly ash berries rose as the sun warmed the mulch. There was no sign of the garter snake family. True to their word, the men had left the red cedars, lopping their tops to restrict growth, and trimming the side branches of the white pine.

Despite my conflicted relationship with prickly ash, I felt its shock and pain, the slow dying of roots bereft of branches. No living being deserved to be treated with such callous disregard for the sanctity of its life. I stood amid their tattered remains and offered tobacco, a prayer, my unspoken grief. My useless guilt. Belatedly, my gratitude for their gifts, for their tenacious lives. My apology, as well, that I had allowed this to happen. In this way.

Here was my dream made real, the efficient destruction an act of violation. Four men in yellow uniforms come to do harm, not to me, but to the Earth, the Mother, in whose metaphorical dream chair I had been sitting. My dream had warned me of their assault on the plants, of the loud, harsh saws that cut through stalks and leaves, that pulverized them into mulch. In the name of maintenance, they raped the land. A metaphor of the brutal destruction that is intrinsic to a Western relationship with the Earth: dominate, remove, extract. I felt complicit, my silence and inaction a reminder of Paulo Freire’s powerful words: “Washing one’s hands of the conflict between the powerful and the powerless means to side with the powerful, not to be neutral.”1

And yet the man had said, you should plant a garden. The last wisp of dream dissipated, vanishing like fog warmed by the sun, his words creating a common ground between us. He was right. New plants, new prayers, new life would heal not only the wound they left behind but also the deeper scars of an overgrazed land. I could plant more Dakota corn, more food to feed my family, more seeds to share with my community. The men had cleared a tangle of tenacious plants on land that had been beyond my physical ability to reclaim. Was I wrong to feel gratitude as well?

When violence was first used to conquer this land, we suffered devastating harm to the Earth, our children, and ultimately, our identities as Native people. From generations who suffered through boarding schools, who could not keep their children safe, we inherited their fear. The imprint of this generations-old trauma was triggered by the rapid, violent clearing of my land; my response rose from the legacy of my family’s defensive silence. But the story needn’t end there. Through the strength of our ancestors, we also inherited seeds, prayer, ceremony, language, courage, resilience. Hope. The knowledge that we seek is still here, within reach.

As I learned when visiting the Standing Rock encampment that challenged the Dakota Access Pipeline, it is our responsibility as Indigenous people to protect what we love, whether that is water, our sacred first medicine, or our seeds, who give life, or our children, who are the future. When we stumble, when we give in to fear or despair, when we fail to act, what we can do is plant a garden. The simple gesture of planting a seed reconnects us to an ancient relationship; it is a reminder that we are loved, all of us. In turn, we must also love and care for our relatives, all of them.

I come full circle back to where this story began, on a hillside covered with prickly ash. I am writing in winter, filled with dreams for my garden when the snow melts. I dream of a hillside filled with new plants that grow alongside a small clump of prickly ash, just enough to feed the butterflies and provide medicine for those who need it. When the time is right for me to arrive with my lopper, I will come bearing tobacco and prayers as well.

Mitakuye owasin, We are all related.

This essay is an excerpt from Kinship: Belonging in a World of Relations—a five-volume collection edited by Gavin Van Horn, Robin Wall Kimmerer, and John Hausdoerffer.

- Paulo Freire, The Politics of Education: Culture, Power, and Liberation (Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing, 1985), 122.

A Little More Than Kin

Reflecting on whether there is a genetic basis for altruism, Richard Powers looks at how human beings find kinship with other creatures.