Bathsheba Demuth is an environmental historian, specializing in the lands and seas of the Russian and North American Arctic. She is the author of Floating Coast: An Environmental History of the Bering Strait, which was named a Nature Top Ten Book of 2019, listed as a Best Book of 2019 by NPR, Nature, Kirkus Reviews, and Library Journal, and winner of the 2020 George Perkins Marsh Prize. Her other writings can be found in The American Historical Review and The New Yorker.

Sarah Gilman is a Washington State–based writer, illustrator, and editor who covers the environment, natural history, science, and place. She aims to cultivate wonder in hopes that it will help more of us come to value and make space for wildness and each other. Her work has been published in The Atlantic, High Country News, and Hakai Magazine.

On a moose hunt north of the Arctic Circle, Bathsheba Demuth observes two contrasting narratives manifest along the banks of the Ch’izhìn Nji: one of conquest, another of quiet knowing and restraint.

At first there is just the too-dark flicker, a void of color in the green. Along the river, muscular willows pack the shore to the waterline. Alders root in the drier soil of the cutbank, holding their branches nearly in parallel with walls of earth that rise ten, fifteen, sometimes fifty feet over the water. Where the banks end, the land plateaus, rolling out under the sky with a cover of black spruce, their trunks narrow from the effort of growing in permafrost. The peak of Arctic summer in the north Yukon is just beginning to tilt toward autumn yellow and red.

As we move upstream, the foliage blurs into an anticipated order of branches and leaves. The dark break in this pattern sends a startle down the optic nerve. The shadow moves again, before its formlessness resolves: a moose. Head lifting, he steps clear of the willows, keeping one round eye always on us. Like other deer species, he probably does not see in color but rather in shape and movement; we are, in his gaze, a space of solid dark motion where there should be river.

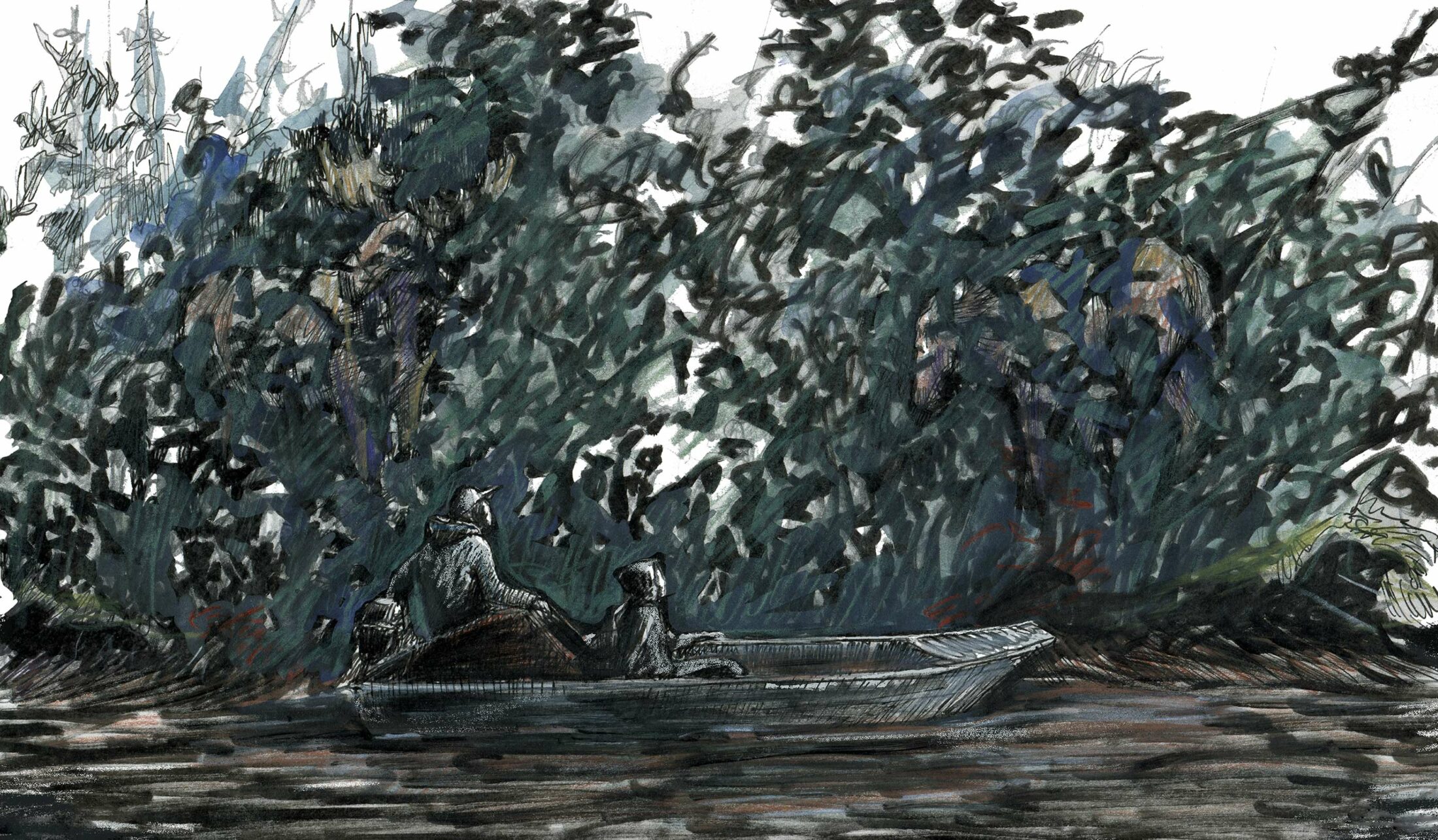

Stanley cuts the engine and reaches for the rifle. We have come to hunt on the Ch’izhìn Njik—a river you will call the Eagle if you believe the stories told on the two-dimensional face of maps. There are just two of us in the open metal boat, fifty or so miles north of the Arctic Circle and a hundred and fifty miles south of the Beaufort Sea: Stanley, in his sixties, with Gwitchin ancestors who go way back on this land, beyond names; I the age of his children, with only two decades of history here, and all of it in Stanley’s company. We are a day out of Old Crow, the village where Stanley lives. All morning, boats heading back to town pulled alongside us, their drivers shouting news over the motor din: moose near Johnson Creek; caribou at the mouth of the Miner; a bear at the slough. Several sat low in the water, heavy with carcasses wrapped in tarps, their corners held down by the boney spans of antlers. But for hours after that we saw no other people. And no moose.

Drifting alongside him now, we see he is small, only four or five hundred pounds. A yearling, Stanley says, and puts the rifle down. The moose snorts at the sound. Hooves leaving gouges in the mud, he trots up the cutbank. Gone but for a quiver in the leaves. Stanley starts the motor and pulls into the current.

In the sun the temperature is in the low fifties, but in the open boat the wind is frigid, piercing layers of parka and the canvas I have pulled to my chin. The lull of the engine makes it easy to fall into reverie, disassociating from numbing fingers and stiffening muscles by retreating into the story-house of the mind. But many years of Stanley’s company has taught me to pay attention; no tale should keep you from watching. A ripple on the water may signal a submerged branch. A dense shadow among the shrubs might be a bear.

Change in a pattern in the land is no danger if you see it in time.

There is a kind of story about the Arctic that you’ve probably encountered if you’ve been alive in the English-speaking world in the last century: a white man—almost always—goes north, where he is tested and finds something. In childhood, the versions I heard came from Stan Rogers’s baritone, the hand of Sir John Franklin “reaching for the Beaufort Sea”; or in Jack London’s tales of heroic dogs and unlit fires at bedtime. Robert Peary tried for the North Pole in the National Geographics I inherited from my grandfather, as did men who were born too late to plant imperial flags but could ski alone into the blue ice, blackening their cheeks with frostbite in the name of self-discovery.

In the boat, riding the silver line of the river, I think about the day almost exactly twenty years ago when I began to learn how some stories can fail you.

I had been in Old Crow only two days and had not ventured beyond the village. I followed a gravel road out of town until it faded into a mud four-wheeler track along the shoulder of the nearest low mountain. As I climbed beyond the black spruce tree line, I could see that not far ahead I would be alone on the tundra. The slopes and hills rolled on with the kind of grandeur that made me feel I was in the Arctic wild, at last, the only way you could be: alone.

The path took me into a stand of willows, yellow and full of sun: like walking into a bloom. At some point I glanced down. There in the mud were my boot prints, woven among the tracks of a bear. Hind paws long as my two palms. Water seeping darkening pools into our mingled trail. He was close. A dark shape just out of sight. But unseen does not mean unfelt; my body was nerve-raw with fear. I turned, shaking, and walked back toward town.

I shook often in the presence of animals that first autumn. I was working for Stanley as an apprentice dog musher: a job redolent, in the abstract, of adventure. I imagined sledding into some cold, still moment behind a team of dogs eager to obey. And I loved dogs. Or I thought I did, having rambled Iowan woods with childhood pets. In the dog yard, where thirty or so huskies circled their wooden houses in a stand of dry spruce, was a different order of canine. Pet dogs attend to their people; huskies attend first to each other, at least until you earn their trust. To my untrained eye, some looked like wolves, their gazes appraising me and bodies coiled with muscle, howling and yipping at my intrusion. The idea of commanding them was comical. I assumed I would be bitten.

Among dogs and bears I felt fear but also disorientation, as I realized that the stories I knew, of solitary adventure, were worse than useless here, in an Arctic so alive I was never alone. The stories I knew were dangerous. Franklin, as Stan Rogers sang, left only weathered broken bones—Franklin, who no more asked the sea ice to suffer his passage than the Inuit how to live in their land, the land he died crossing. Heroes seek discovery, not permission. They also die.

Back on the river, the pattern breaks again: a sudden sense of being in shade, although the sun is bright. The bank to our left, rising fifty feet above us, has split and caved in on itself. A vast gouge remains, the solid darkness of soil stripped of growth. Half the river channel is blocked by an earth-berg, large as a small house, the trees that were once its surface half underwater. There is a strong odor of decay. Layers of dead plants and lichens in the permafrost, their decomposition long deferred by cold, lie open to warmth and rot. Stanley slows the boat, easing us through the narrows.

It is the largest collapse we have passed, but not the first. Early in the day we saw a slumped shore, which seemed unremarkable, as rivers always erode and shift their beds. Then we passed another. And another. Banks had lost all coherence, like a bag of flour slashed open. Dark loam spilling down and dissolving into the river. Over the gunwale, passing the most recent slump, I see birch branches swaying in the current. The leaves are still green.

Up the river, more. The sun is swinging low and westerly: we need to make camp soon. The land is low and flat, much of it covered in muskeg too wet for sleeping. Geese rise before us, honking their complaints at our disruption. Two bald eagles keen from a thermal. Shadows under the bank lengthen. At a turn in the river, almost a corner, Stanley pulls to shore. We clamber out of the boat, awkward in our layers and life jackets. Thirty feet or so above the river is a dry place. Under tall spruce, a scattering of cranberries. This will do, Stanley says.

We slip and pant and swear our way up the steep, muddy bank to set the tent. A wall tent requires making a frame, like a three-dimensional stick drawing of a house, out of spruce poles. I hold them at right angles while Stanley does the knots. With the skeleton in place, we hang the canvas tent from the center pole, Stanley whistling through his teeth, and tie out the sides. I cut spruce branches to cover the floor. Stanley retrieves a small metal stove from the boat and rigs the pipe. With more slipping, we haul the rest of our kit into the tent: two axes, two rifles and a shotgun, sleeping bags, caribou hides, spare boots, a crosscut saw, a bag of ammunition, a purple Rubbermaid tub filled with food, backpacks with clothes. There is camping and then there is living somewhere, just not permanently.

At sunset we are in the tent with a fire in the stove. It smells of fresh-cut spruce and frying bacon. The tent faces upriver; with the flap open, we can drink tea and keep watch for moose. It looks like snow tonight, Stanley says, gesturing at the edge of cloud pulling darkly over the northern horizon. The gentle murmur of geese drifts up from where they paddle a quiet eddy. The evening sun, not yet caught by the night’s clouds, casts a warm glow over the taiga, a photographer’s light, showy and golden. I have a sudden sense-memory of National Geographic: clay-coated pages, thick and glossy, an inky smell hovering over the image of an angular wolf, leaping. Animals rarely appeared with people or with the tessellated fossils illustrating some geological event. Each issue unfolded in separate dispatches from the country of humans, or the country of all other life, or the domain of stones.

All moose begin as stone.

The taiga’s pulse of winter freeze and summer thaw grinds rock into dust, as do the rasp-tongues of glaciers high in some mountains. Streams suspend this silt in their waters and feed it into rivers; rivers flood, coating their shores in a slick of young soil. Willows push out sprouts, their roots drawing nutrients from the mud into new leaves rich in phosphorus and calcium. From rock-born elements, willows condense the raw stuff of bone and flesh. You might not think so by looking at it, but the green gauze of foliage is dense with protein. Moose gorge, stripping catkins as the snows melt, using their flexible noses and lips to select new leaves. A bull grows forty or fifty pounds of new bone in his antlers each summer; a yearling will add nearly the same to lengthen her femurs and widening scapulae. A grown cow sets no antlers but must nourish the bones and tissues of her fetal calves.

The moose we kill is among her willows, standing in the reddening dusk. In her second year, with no calf, she is alone. We come to her two days after making camp. The first morning dawns to a wet inch of snow on the tent roof. We spend a long morning by the stove, Stanley sipping coffee from a metal bowl—cools faster, he explains—and talking, pulling back the tent flap now and then to watch the river. No moose. By noon the sun is warm. We head upriver. No moose. After an hour, Stanley cuts the engine and we drift back toward camp. Flat land wide under the sky, the horizon pricked by the knotty tops of spruce.

And more eroded banks. In places, a carpet of mosses and berry roots hang a fraying edge over the maw of absent earth. The erosion is most common in the direct exposure of southern and eastern slopes. “No one pays enough attention to this,” Stanley says, gesturing at the slump. “Look at how cloudy this water is. All that erosion ends up in the river. It’s bad for the fish. It’s bad for everything that eats the damn fish. We eat the damn fish. But erosion isn’t exciting. Everybody wants the icebergs melting.” We fall silent then, drifting on the current.

I read, shortly before coming to the Arctic, that the air over northern Canada had warmed 2.3 degrees Celsius in the years since Stanley was born. The same atmospheric warmth provoking the charismatic dissolution of Greenland or Antarctic glaciers is at work on the flatlands of Ch’izhìn Njik. The permafrost, which runs through this earth like a dispersed spine, is liquifying. But knowing causes is not the same as making sense. The earth is ceasing to cohere: how to make that coherent? The way I know to do this is with the pattern of a story. But what we see on the river has no end. We are telling from a middle or a beginning, with no view of where it will resolve.

The earth is ceasing to cohere: how to make that coherent? The way I know to do this is with the pattern of a story. But what we see on the river has no end. We are telling from a middle or a beginning, with no view of where it will resolve.

It is simpler to tell the end of the moose, for it is clear why she dies. Her body will feed us and others back in town. Stanley slows the boat and brings out his rifle. I take the wheel. He sights her in the scope at fifty yards. Her ears prick in alarm.

Moose have many ways of evading danger: running, or hiding where they can smell and hear threats approach, or swimming. Some will even charge. This moose stands her ground, stamping once, shaking out her long neck and jutting her nose into the wind.

Then comes a sound like the air splitting: the contained explosion of the bullet echoing off the water. The moose’s front knees buckle. She bows, then shudders to the earth.

Doing right by her carcass takes hours. Just as there is no ease in killing, there is labor in gratitude, and an acute sense of our dependence on this animal. We cut willows to lay in a clean bed beneath the dark form. Spread a new tarp in the boat to hold the meat. Sharpen knives. It is skilled work to peel skin from flesh, to sever bones from each other at the joint, to skim around bundles of deep-red muscle. Stanley tells me where to hold a leg or pull taught the edge of hide as he peels it back. The fur under my fingers is damp from the wet grass. The air smells of blood and crushed plants, and occasionally the thick rot of digestion. The minerals moose consume in plant tissue feed colonies of bacteria in their gut, which, in turn, moose metabolize for protein. A moose rumen contains an entire microscopic world.

I take a turn skinning, crouched over and sweating. I am not fast or more than barely competent. We will be hungry soon, so I hand the knife back to Stanley and gather dry brush to make a fire; fetch a pot from the boat and fill it from a small stream. Stanley cuts strips of fat and muscle, which I add to the pot. In an hour we will have boiled meat.

Tending the fire, I think again about that first autumn in the north. I never saw a bear, or one never consented to be seen. The dogs began to acknowledge me with wagging tails and ears swiveled slightly down, a signal of growing affiliation. But I went mute for some months. The myths of Arctic emptiness and grandeur were deadly. What are heroes, after all, but people so singular in their focus that they see little else but their goal. Inattention raised to a virtue. And for what? For, as Stan Rogers sings, a lonely cairn of stones?

I had no words until we came back from hunting the first moose I saw die. Stanley sent me to bring the tongue and belly fat to an Elder named Tabitha, who lived across the dusty street. Tabitha scared me a little; my incompetence and foreignness felt acute in her presence. But that afternoon I could say: “We went upriver for moose. It was a bull. Can I make you boiled meat?” Even I could boil meat. We would boil more than one pot together.

Tabitha’s parents were born before Old Crow was a village, when the Gwitchin moved widely and seasonally across their land. The whole wide country was home. Settlement here is a recent and intrusive thing, brought by a colonial state keen on narrowing the sphere of human presence so the rest of the land might appear bare and unused. The myth of exploration, of men going into some empty wild country, is a fiction of conquest: if no one is here, it can be claimed. If people are there, move them and call their vast homelands Crown Land.

Now, Stanley and I pause to eat boiled meat. Alone, without this moose, we would be lesser, and hungry. Carrying the parsed carcass to the boat, Stanley groans under the weight of the shoulders and haunches. I follow with the carefully cleaned stomach, the sheets of ribs. Before we head back to camp, I wash my hands in the creek that veins down through the shoreline grasses. The water is reddish; there is iron in the land’s bones, and the tannic acid spruces release as they decay in the damp muskeg leeches trace metal from bedrock. Wolf prints rim the stream. More than one, it seems, from their interlaced patterns. Perhaps they came during their own hunt, stopping to drink where the water pools. Down the sloping bank, the stream gurgles as it joins the river, a capillary merging with an artery sunk in the flesh of the landscape.

Stanley told me once about a paleontologist who came to Old Crow asking after signs of extinct animals: mammoth tusks exposed in a riverbank, or the corrugated paddle of a mastodon tooth. An Elder showed the man to a place along a river and told him to dig, explaining that it was where the people had seen the last mammoths kneel down on the earth and die. The paleontologist dug. In the bank were bones; the animals who made them last walked—if you mark time as geologists do—at least ten thousand years ago, when the Pleistocene Epoch gave way to the Holocene.

One way to make sense of the Ch’izhìn Njik’s collapsing banks is to call them part of the Anthropocene, the epoch after the Holocene. For geologists, an epoch is determined by a change to earth systems so dramatic it is written into rock strata: the advance of an ice age, or its ending, as when the mammoths died. There are many candidates for the Anthropocene signature: sedimented plastic, nuclear isotopes, a climate warmed by burning ancient, fossilized growth. Whatever the mark, the maker is human; our influence is so ubiquitous and consequential, the argument goes, the stones will tell of us ten, fifty, a hundred thousand years from now. Even Homer’s heroes, lusting to sing their names into the hereafter, could only dream of being indelibly told into the earth itself.

“Anthropocene” is a word but also a story. A story where the hero is not an individual but a species. In it, Homo sapiens carry a tectonic if unruly power, singularly able to shape the fate of all life. Able to make the land itself kneel down. Some tell it as a story of ultimate exception, of humanity so broken free—by technology and cunning—from natural processes that we can alter our surrounds, from molecule to mountain, and emerge triumphant, for a time. Others make the Anthropos a self-defeating conqueror: a Franklin-figure, not charting maps but remaking the contours of continents.

Tragic or victorious, the Anthropocene offers an ending, one foretold in the lullaby of a deep future, when the epoch inevitably closes and sets our bones adrift in the strata, like those of the mammoths before us. A cold comfort, but coherent. A story not about Earth as home, but Earth as a thing we mark, in the course of an adventurous visit, and leave. It is also an abdication that makes destruction for which specific societies are responsible innate in our species-being. All humans become excessive in the same way all moose eat willows. Gorge, she does. Gorge, we do.

Never mind that the moose also fasts.

All winter she will eat little; her bones thinning as she loans protein and calcium to the next generation. If she becomes pregnant in an abundant summer, she will likely bear twins. When the land is less prolific, she will carry a single fetus. In summer, as she nurses, the moose will eat judiciously, pruning rather than razing even the feltleaf willows she prefers. A stripped plant cannot regrow and will in a few generations cease to provide any nourishment; a grazed willow grows more, brooming out shoots and catkins. A moose recognizes—how you ask, and I have no answer—that she gives birth not just to her progeny but to the landscape they inherit, a landscape she makes in part by eating from it.

After some days, we break camp and start back downriver. We see a dozen more moose: cows with calves, yearlings, a bull with antlers white and clean of velvet. Each glossy brown body, like any of us with mortal flesh, a substantiation of rock, water, sun, and tissues given by others. A body, after all, is just a cacophony of transformations briefly stilled into an individual form. To make that form, generations of moose—as well as generations of their Gwitchin hunters—change the world around them, constantly and irrevocably. A willow leaf, once eaten, is gone. The moose in our boat will never breathe again.

But eating a moose or grazing a willow does not foreclose or damage the existence of other moose or other willows or other people. Perhaps this is part of what heroic stories elide. By idolizing change that shunts other possibilities, that leaves a mark—a cairn, a settlement, a stratum—these stories have no place for the useful metaphor of the moose’s restraint, or the ethics of her longtime hunters. I think of Tabitha and her grandparents and great-grandparents, whose presence here was dismissed because they left no sign legible to the colonial eye. In that gaze, the absence of scars on the land became an absence of knowledge and claim, a place open for gluttonous maps to discover. The Ch’izhìn Njik re-marked as the Eagle River.

But stories of gorging heroes have failed, and at scale. That failure is visible in the erosion along the river. Stanley asks me to photograph it, slowing the boat as we pass the inchoate places. Kneeling in the boat, the slumping land in my viewfinder is clearly neither at its beginning nor an end. We, you, are in the midst, in the current. Not everything will resolve in the brief years we have alive, together. But there is time to listen for stories that are not lethal. To see a new pattern in time.

To the north, the mountains still carry snow. If we followed the river, it would come eventually to the Bering Sea, and from there mix with the tides. We ride the silvering line downstream, sunk into the earth by the passage of time and water, under the wide sky.

Reindeer at the End of the World

Ecological historian Bathsheba Demuth explores the allure of the apocalyptic arc—the promise of a new world—and the rise and ruin of the Soviet ideology that sought to impose its utopian vision on the Native Chukchi people, their herds of reindeer, and the natural cycles of the Russian tundra.