Chelsea Steinauer-Scudder is a writer based in northern New England whose work explores the human relationship to place. Her essays have been featured in Crannóg Magazine, Inhabiting the Anthropocene, and EcoTheo Review. Her forthcoming book is Rebirth: Mothering Through Ecological Collapse.

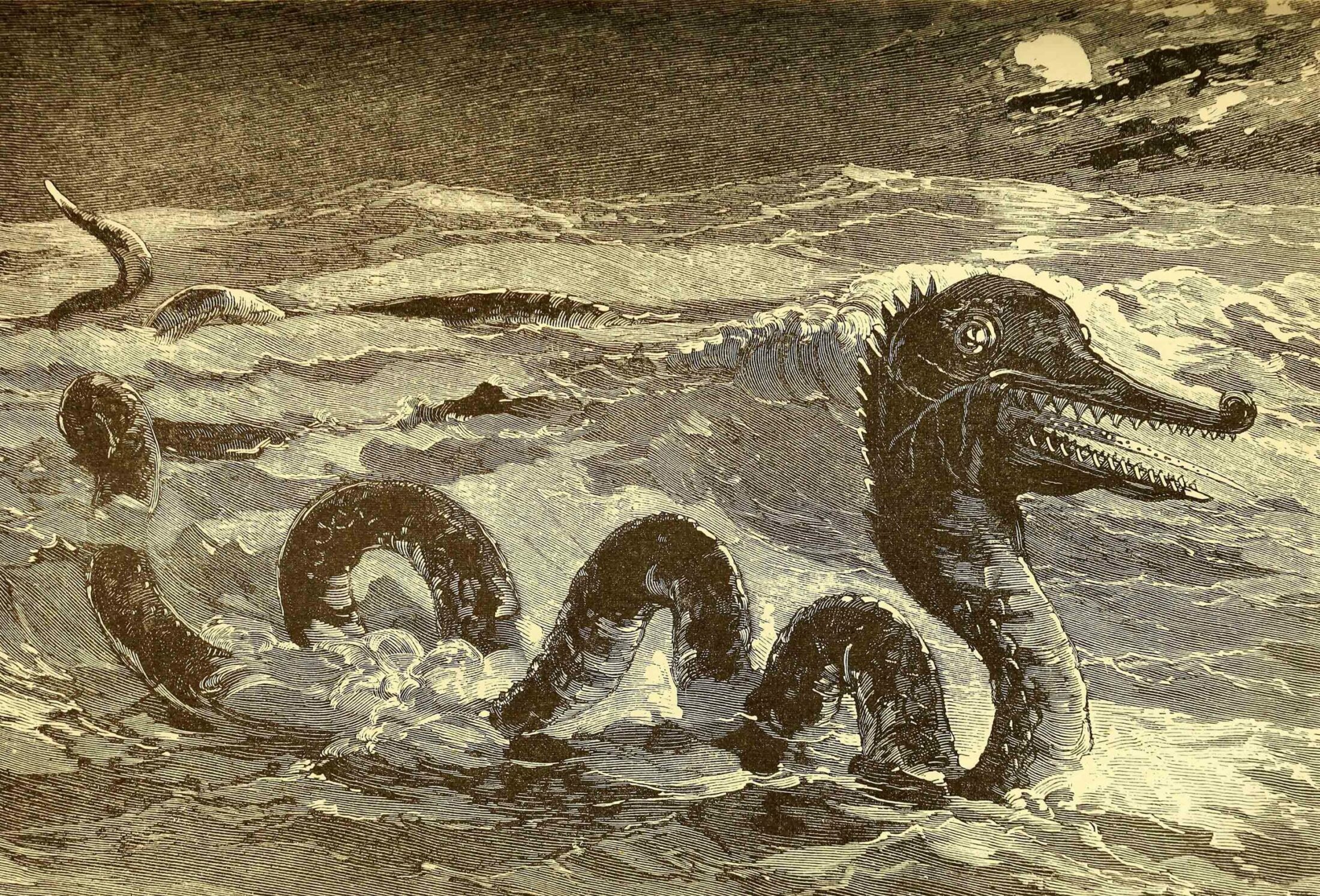

Sea monsters have long roamed the dark waters of legends, embodiments of a wild and chaotic power. After reading numerous accounts of sea serpent sightings off the coast of Maine, reported over the last two centuries, Chelsea Steinauer-Scudder considers our relationship to fear and how monsters could function in a modern mythology.

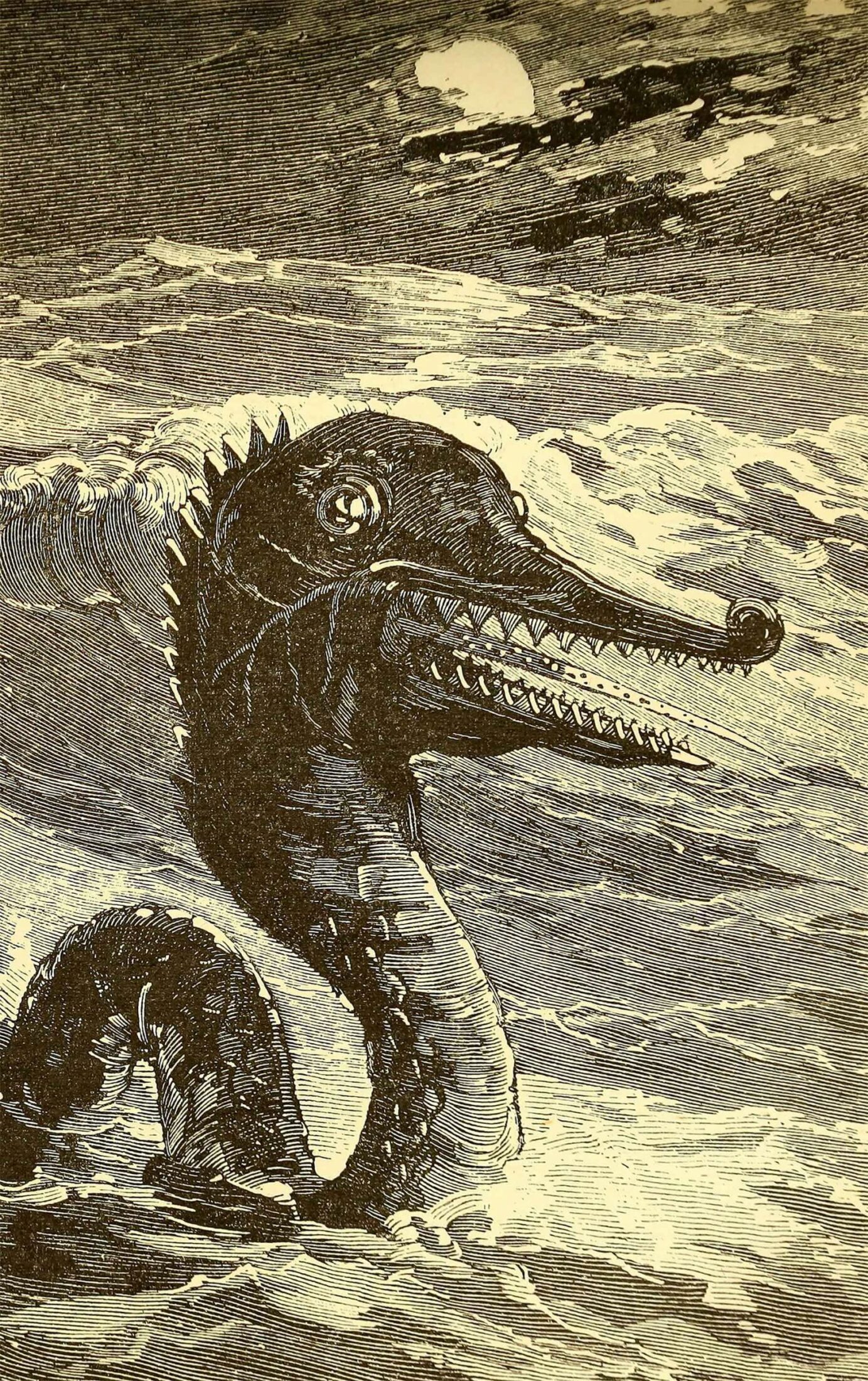

In 1779 Edward Preble, an ensign on the ship Protector, spotted a great serpent in Penobscot Bay, off the coast of Maine. Ordered into a longboat, Preble approached the beast—whose head rose several feet out of the water atop a thick neck like that of a giant snake—took aim, and fired a shot. He missed. The creature vanished beneath the surface, never to be seen by Preble again.

Nearly forty years later, in the summer of 1818, a serpentine monster was sighted from Week’s Wharf in Portland Harbor. In 1836 Captain Black, aboard the schooner Fox, reported a sighting of a snakelike creature in the seas near Mount Desert Rock. Major General H. C. Merriam and his sons were sailing to Wood Island Light in 1905, when they spotted a “monster serpent,” which proceeded to swim circles around their boat. In 1910, from the deck of the steamer Bonita, passengers saw an eighty-foot-long black beast with white spots arc through the water.

In local folklore these sightings have cumulatively been attributed to the mysterious existence of the Casco Bay sea serpent, an elusive monster ever roaming the cold Atlantic waters off the coast of southern Maine.

Beasts of the ocean have been lurking in human myth and legend for nigh on millennia, and their existence in the literary canon begins with some of our most ancient recorded stories. In the Rig Veda, a Hindu text composed around 1500 BC, Vritra is a water-hoarding dragon, defeated by the god Indra. Jörmungandr, the Midgard serpent, is the sea beast of Norse mythology, the archenemy of Thor. In the Babylonian creation myth, Enuma Elish, Marduk, a young god, defeats the dragon Tiamat, goddess of the seas and the embodiment of chaos. When she opens her jaws to devour him, Marduk causes a tempest to enter her mouth, and “the fierce winds fill her belly.” With a single arrow, he then splits her in two. The Tigris and Euphrates Rivers flow from her eyes; from her body, he creates heaven and earth.

In Homer’s Odyssey, Odysseus must navigate his ship between Charybdis, the treacherous whirlpool, and the terrible Scylla: “Twelve foul feet bear about her ugly bulk. Six huge long necks look out.” She devours one of his men for each of her six heads. The Semitic deity Yamm, meaning “sea” in Hebrew, was ruler of the oceans and waterways. This same deity appears in the ancient Canaanite stories of Baal, myths etched into stone tablets, discovered in the ancient city of Ugarit in modern-day Syria. In this cosmogony, Yamm, the primordial chaotic force, is the god of storms and raging seas, slain by the hero Baal.

From Yamm we later get Leviathan, who makes a number of appearances in the Old Testament. In the Book of Job, a lengthy description of this untamable beast is used as a metaphor for the creative power and might of God:

It makes the depths churn like a boiling caldron

and stirs up the sea like a pot of ointment.

It leaves a glistening wake behind it;

one would think the deep had white hair.

Nothing on earth is its equal—

a creature without fear.

It looks down on all that are haughty;

it is king over all that are proud.

(Job 41:31–34)

In these ancient myths, our primordial fear of the uncontrollable is entwined with the sea monster: a terrifying being who masters the tumultuous oceans, embodying the reign of great and awe-full powers at work in the world. If and when the monsters are defeated, it is not by human will but by other divinities, who are themselves associated with natural elements, often rain and fertility. Tiamat is defeated by the young god Marduk, Yamm by Baal. Vritra is slain by the deity Indra; Jörmungandr and Thor are destined to slay each other. The power of the sea monsters both originates in and is able to be quelled by something other-than-human, something beyond our grasp. The mythic fates are, in the end, set in motion by forces not our own.

For arguably our entire conscious existence, humans have grappled with the paradox of control and chaos: here we are in the world, sentient beings who perceive so much and create so much, and yet we are mortal. Throughout our history there have been forces at work beyond our understanding, which may, at any time, wrest control of our lives from our hands: volcanoes erupt, cold descends, the earth cracks apart, the food runs out, a beast rises from the murky depths and devours us.

The sea, in particular, has maintained a degree of mystery in the imagination as an inhospitable realm where we are not able to so readily work our will. “Yes, I love the sea. It is everything,” says Captain Nemo, aboard the Nautilus. “It covers seven-tenths of the globe, it is a vast desert where man is never alone, since it teems with living things. The sea doesn’t belong to tyrants, they can still fight on the surface, but thirty feet below, their power ceases. Ah, only in the sea can I be a free man!” When Jules Verne created his tragic hero, who needed to escape to the only place on earth where man has no power, he sent him to the bottom of the ocean.

The mythic fates are, in the end, set in motion by forces not our own.

The existence of sea monsters in myth acknowledges the unknowable will of the wild—a reminder of a relationship with a wider, untamed world. That these monsters are often slain perhaps indicates our desire to exist within a disciplined reality. And yet, these stories acknowledge a balance between creation and destruction, chaos and control, order and disorder. One may not win out entirely. Thor dies after slaying Jörmungandr. Odysseus has no choice but to sacrifice part of his loyal crew to pass by Scylla.

In a modern Western reality, an implicit—and often explicit—perception of control infuses the dominant value system, particularly when it comes to nature. There is a notable strain running throughout mainstream culture that seems particularly invested in the belief that humans are individual rulers of their own lives, that order has triumphed over disorder, that there is little room in practical life—maybe even in imagination—for the uncontrollable wild.

According to this dominant view, humans are entitled to make all manner of choices regarding the natural world: they are justified to fell forests and raze mountaintops, or plant forests and protect mountaintops. This view presumes that we are the ones who may decide. So much is thought to be within human control, in part because so much is thought to be within the bounds of our understanding. Science can access the mechanisms of the very forces of life, down to subatomic particles, and can see almost as far back as the first instant of the Big Bang. The reigning narrative depicts a reality in which the nonhuman realms—places where the primordial forces of the unknown wild could still be waiting to snatch us from the shadows—remain on the margins of civilization.

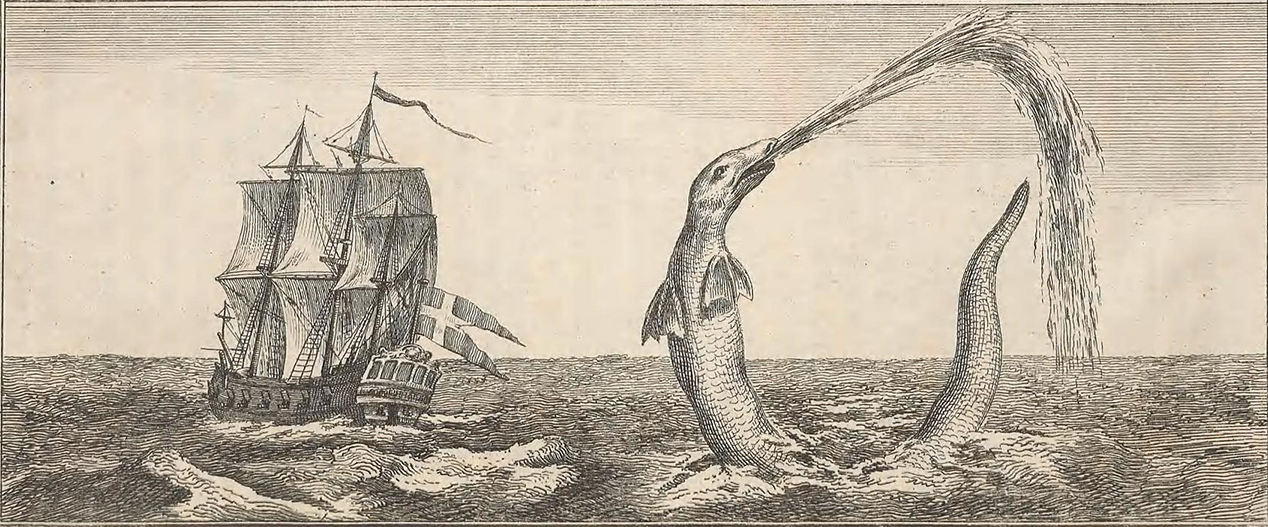

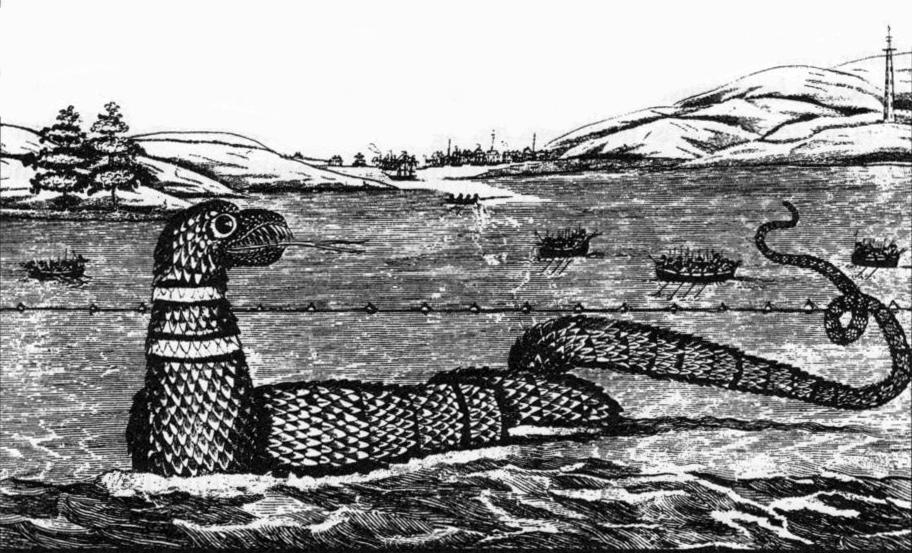

Berthelson, Andreas; Pontoppidan, Erich / Wikimedia Commons

And yet … to what extent is this ordered, separate, human world illusory? We are mortal, susceptible to forces we ultimately cannot wrestle into submission. The attempt at too much control comes with consequences. We are in the midst of the sixth mass extinction our planet has seen, this one caused by human activity. Oceans are rising. Droughts are worsening. Most of the topsoil is gone. In a modern, human-driven myth, humans play every part: warrior, god, monster, those who fall. The prevailing narrative of today, despite its claims toward order, has not found a way to harness raging storms and fires, vanishing species, extreme heat and cold. It has largely ignored the stories of the people who are displaced, homeless, thirsty—those who face the consequences that arise when other mortals challenge the greater forces at work in the world, believing they may don the armor of the ancient gods.

A primal sense of fear has been present in the human brain since the most ancient of our ancestors roamed a younger planet. The predominantly rational worldview of today has not evolved us past such instinctual emotion; fear is innate and visceral. But what do we do with it? Unable to shake free of primeval fears and yet widely ensconced in a modern mindset that has allowed little space for fear of the wider unknown, humans seem inclined to turn fear inward, to direct it at ourselves and each other. Perhaps there was value in the old, archetypal myths that could take primordial fear and transform it into a terrible dragon, or that could manifest a sense of universal chaos in the writhing body of a serpent. Myths allow fear to be a gateway to awe. They allow sea serpents and other monsters to be harbingers of a much greater world, reminding us that we are not meant to control everything; that fear, well-placed, can serve a function in a now widely forgotten relationship.

There is a distinct desire for such monsters to be definitively real.

Inside the International Cryptozoology Museum in Portland, Maine, the Casco Bay sea serpent—in recent years nicknamed “Cassie”—is one of many displays, nestled among more recognizable “cryptids” like Bigfoot, and more obscure ones like the Dover Demon. Cryptozoology is the study of hidden animals, creatures believed to be real but whose existence cannot be confirmed due to lack of scientific proof. The museum features plaster castings of giant footprints, illustrated renderings of chupacabras, a taxidermy beaver placed next to an Indiana Jones action figure and a sign reading, Do Giant Beavers Still Exist?

In the sea monster section of the small museum, model ships sit inside glass cases. Journals are propped open to reveal weathered pages, detailing encounters and sightings of giant serpents. Peering at the display, one is inclined to conclude that in our modern age, monsters have been pulled out of a mythological context and shoved into a rational and scientific one. From here they are either dismissed as folly or humor, or they are believed to truly exist, in an intellectual, material sense.

For many of the museum’s patrons, local folklore such as this is simply fun. They wear a quiet smile through the exhibits, never believing that such fantastical creatures swim the waters or roam the woods. But to believe in Cassie, for the cryptozoologist and a good many other twenty-first-century hominids, is to search for scientific proof of her existence. It is to set out on Casco Bay and watch the undulating sea, waiting for something matching Edward Preble’s original description to raise its large head out of the waters. It is to point to the collected accounts and cry, “Evidence!” There is a distinct desire for such monsters to be definitively real.

On June 5th, 1958, Ole Mikkelsen was out to sea on his fishing boat in Casco Bay, five miles off Cape Elizabeth, on a day like countless others he’d had in his forty years as a fisherman in Maine. But on this morning, something large appeared on the surface and began to move slowly toward him, seemingly curious about the nets trailing from his boat. All of a sudden, it dove, revealing a large, forked tail that vanished beneath the water. A few seconds later, the creature reemerged, its broad head held above the water atop a thick, snakelike neck. As the lightship blew its horn in the distance, the beast slowly rotated its head toward the sound. Mikkelsen figured it was at least a hundred feet long.

This remains the most recent trusted sighting of the Casco Bay sea serpent, so similar in description to the creature Edward Preble saw nearly two hundred years earlier. And what are we to make of such accounts today? How do monsters function in a modern mythology, where they still ride the currents of our psyche, surfacing, on occasion, as fantasy or fact?

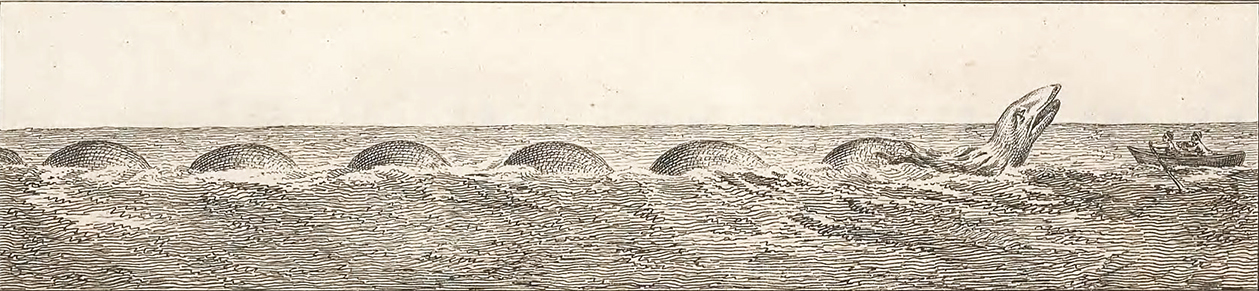

The Gloucester Sea Serpent of 1817

Wikimedia Commons

There is little room in practical life—maybe even in imagination—for the uncontrollable wild.

Perhaps there is something greater at stake in these modern tales of sea serpents, not just for the cryptozoologist but for the place of myth and fear in the modern world, where monster legends no longer have an obvious place. Maybe we still need stories that account for the inexplicable forces that have long haunted humanity, that steer the dominant narrative back into balanced waters, where it might exchange some amount of control for the humility that comes in the wake of awe.

It could simply be an amusing anecdote when a modern human being ventures out to the water hoping to be the next to sight the Casco Bay sea serpent—someone taking an outdated and whimsical story too far. Or, perhaps in the sighting of monsters is a subtle nod to something greater than the human-centered story so many of us encounter every day, an opening into a distant memory of the time when chaos and control were understood as partners in a perpetual dance, one which encompasses all that has been and will be created, all that has been and will be destroyed. Creation cannot exist without destruction. We cannot have awe without fear, wonder without terror.

I’d like to think that the great sea serpent of Casco Bay is out there somewhere, an echo of those ancient beasts, quietly tapping on the door so many of us have closed, whispering in our ears: Your created world is only a fraction of what is here. Do not bury all of your fears; do not sacrifice the inexplicable. It is in you, as it is in us.

Berthelson, Andreas; Pontoppidan, Erich / Wikimedia Commons