Elizabeth Rush is the author of The Quickening: Creation and Community at the Ends of the Earth and Rising: Dispatches from the New American Shore, a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. Her writing has appeared or is forthcoming in The New York Times, The Guardian, Harpers, Granta, Orion, and others. Rush is the recipient of the Howard Foundation Fellowship awarded by Brown University, the Society for Environmental Journalism Grant, the Metcalf Institute Climate Change Adaptation Fellowship, and the Science in Society Award from the National Association of Science Writers.

Aboard the first shipbound expedition to the Thwaites Glacier in Antarctica, writer Elizabeth Rush puts her ear to this massive body of ice to listen for the messages embedded in its shifts and shatterings. But can something so large, so vast, so ancient, ever really be witnessed up close?

In January of 2019, fifty-seven people gather in the low-slung port town of Punta Arenas, Chile. We are sedimentologists and ship captains, radio reporters and electricians, marine mammal specialists and submarine technicians; the members of the first shipbound expedition to Thwaites Glacier. Everything we do on our last night on solid earth anticipates what we will soon be without. Some call the children they are leaving behind. Some call credit card companies to set up automatic payments. And some head to the Colonial for a couple of drinks. One person runs along Route 9 to stretch her legs, while another runs to the market to purchase deodorant and a couple empanadas. I go to the steam room just above the hotel’s casino. Then I go to the bar around the corner for my last pint, where I eye every person who enters, wondering if we will sail to Antarctica together.

When I was invited to participate in this mission as a writer-in-residence, I imagined that I would spend a significant amount of my time on the boat interviewing my shipmates. The stories I am interested in trying to tell often begin by paying attention to people and places long locked out of traditional environmental narratives. Antarctica itself, while present in the turn-of-the-century tales of derring-do and conquest that define it, tends to serve as a backdrop for a certain kind of hypermasculine posturing. Or as Sara Wheeler put it in her book Terra Incognita, over much of the past two hundred years “the continent was little more than a testing ground for men with frozen beards to see how dead they could get.” In order to avoid this trope, I knew I would have to listen to the lesser-heard voices I encountered on this journey, in particular to the women and people of color who are often omitted from these explorer narratives. I also figured that ice had something to say, was another kind of speaker that regularly went unacknowledged; but if I am being honest, I knew next to nothing about how to listen to it. On the eve of departure, I am nervous about a lot of things: about being one of just over a dozen women on the boat, about whether or not I will be able to hear what the ice is saying, and also about the fact that this might be my last opportunity to be alone for well over two months.

The next morning at breakfast, I gaze through the restaurant’s smudged glass at the R/V Nathaniel B. Palmer. The research vessel looks like a winter slipper with the heel facing forward. The low stern flares into a wide bow with a relatively flat rake, so the boat can ride up on top of the sea ice we will soon encounter, forcing it to break. The Palmer’s hull appears as orange as the inside of a papaya, its superstructure egg-yolk yellow. The Ice Tower, a boxy room with windows on all sides, sits at the very top, a kind of crow’s nest for cold weather. Just beneath it: the bridge, where the officer on watch will oversee ship operations every single minute of every single day for the next nine weeks or more. I wouldn’t call the ship large. It’s roughly the length of a football field, a distance most humans can cross in under a minute without breaking a sweat.

I had been writing about climate change’s early impacts on vulnerable coastal communities for nearly a decade. During that time, I visited with hundreds of flood survivors, many of whom had lost family members and homes. I listened to their stories so that I might learn from them—and better communicate—how to navigate this time of profound transformation. I wasn’t as interested in the science behind the phenomenon as I was in the way our transforming coastline makes us feel. In many cases residents’ bodies were their barometers, telling them that climate change was already with us, now, in the present tense. That there was considerable variability in the future rate of sea level rise was something I had come to accept. Would there be three feet of rise or six by century’s end? No one knew, and I, like those I interviewed, had to learn to live with this uncertainty.

But then I read an article about Thwaites and became uncomfortable again. Should Antarctica lose a lot of ice this century, it will likely come from Thwaites. Thwaites Glacier is comprised of three continuous parts: a floating ice shelf, the grounding line, and the land-based ice behind it. The grounding line serves as a kind of pivot point. All the ice inland of it rests atop solid earth; all the ice on the other side floats in the Amundsen Sea. Scientists suspect that Thwaites is, at least partially, following a familiar pattern of collapse. First, warm water gnaws away at the ice shelf that cantilevers out into the ocean, causing it to thin and eventually break. As the support from that shelf is lost, the flow of the glacier behind it accelerates. Over time, the grounding line—the place where ice and land meet—steps back, increasing the total volume of frozen water making its way into the sea. Melt, thin, break, retreat.

This is the standard pattern for deterioration of marine terminating glaciers. But the particularities of how this process is playing out at Thwaites and the other, lesser-understood mechanisms that might be supercharging it are what scientists don’t really understand, because, prior to our mission, there was next to no observational data on where this glacier discharges ice into the Amundsen. And without that data our models of future sea level rise rates are far more speculative than I had previously understood. What’s clear: in the coming decades, Thwaites will increasingly shape us just as surely as we shape it.

Having spent so much time along our country’s coastlines, with the people whose lives are being actively transformed by what is happening seemingly out of sight at the Poles, I became obsessed with seeing the source of these shifts firsthand. That’s why I applied to the NSF’s Antarctic Artists and Writers Program: I wanted to see Thwaites up close. I wanted to stand alongside this unstable glacier, wanted to witness freshly formed bergs dropping down into the ocean like stones, so that I might know in my body what my mind still struggled to grasp: Antarctica’s going to pieces has the power to rewrite even our most personal maps. I was, at the time, also perched on the edge of a profound personal transformation, or so I hoped: when I returned my husband and I would try to get pregnant. I wondered what my desire to bring a person into the world would do to my experience of Thwaites, and perhaps, more frighteningly, what Thwaites might do to it.

I wanted to stand alongside this unstable glacier, wanted to witness freshly formed bergs dropping down into the ocean like stones, so that I might know in my body what my mind still struggled to grasp.

Over a year before setting sail, I attended a talk by Bathsheba Demuth, a friend and colleague. Her book, Floating Coast, draws together so many different kinds of sources—her personal experience training sled dogs in the Yukon, Indigenous testimonies gathered throughout the region as colonial expansion threatens their lifeways, detailed documents of the subsequent decline of the Pacific whaling industry—all in service of a historical argument that centers the animals and landscapes of the region as its primary actors. At some point in the presentation, the bowhead whales Bathsheba studies make a stunning assertion: We refuse to die for you, in this way, they say in response to the commercial vessels that have arrived in the region. Instead, they flee underneath the floating sea ice. Bathsheba wasn’t suggesting that the whales were behaving as if they were running from the intensification of capital extraction. No, her proposition was far more radical because it wasn’t a metaphor. The whales were using their bodies to critique a way of living that would, should they stick around, destroy them.

I found Bathsheba’s articulation of the whales’ agency intoxicating. I remember thinking, I want to be able to do something like that. Months later, when I learned that I would be spending a couple months plying the ice sheets that swirl around the opposite pole, I finally asked her how I might be able to “get the ice to speak.” As soon as I said the words, I knew that I had put the cart before the horse. I was thinking about recognizing the animacy of the more-than-human world as a linguistic problem. Something that I could, at least partially, solve on the page. I hadn’t yet considered the possibility that I might, for instance, need a translator. Or that my body, so new to the Antarctic environment, might not be properly calibrated to my surroundings. I can boil Bathsheba’s response down to a single word. Listen, she advised. Then she recommended the work of Canadian anthropologist, Julie Cruikshank.

In her book Do Glaciers Listen? Cruikshank chronicles how three distinct worldviews—Indigenous, Western, and scientific—understand the Saint Elias Mountains of northern Canada and Alaska. In some Tlingit stories, glaciers take action and respond to their surroundings. They generate transformation, giving birth to seasons like summer and winter; at other times they swallow humans whole as a warning that others should act with greater humility. “Elders who know them well describe them as both animate (endowed with life) and as animating (giving life to) landscapes they inhabit,” writes Cruikshank. Even though the Tlingit live about as far away from Antarctica as humanly possible, I suspected they knew something I didn’t. That the millennia they have spent living with the ice has made them keenly attentive to its movements and meanings, which is why Do Glaciers Listen? is one of a handful of books I’ve brought along on our mission.

During our crossing, from one continent to another, a crossing which would take over ten days and leave most onboard horribly seasick, I get caught up in Cruikshank’s title. Sometimes I think she is trying to ask if glaciers listen to us, just as Bathsheba’s bowhead whales do. At other times, I wonder if they are listening to each other or forces far more powerful than humans alone. One afternoon, while interviewing Rob Larter, the chief scientist onboard, I decide to ask him whether we might think of Antarctica as not just shaped by human actions but also as shaping us. For a long time, he says nothing, and I fear he is trying to figure out a nice way to dismiss the idea as humanistic sorcery.

“I don’t think I’m going out on a limb by saying that the exceptional stability of the Holocene plays a role in the rise of our particular kind of human civilization,” he finally responds. “Paleo records show us that over the past six thousand years, sea levels have barely changed at all. But if you zoom out just a little bit, you realize that stability is exceptional. Between eighteen thousand and six thousand years ago, the Earth was losing ice very fast, and sea levels were rising, on average, ten meters per millennium.”

“Three feet per century?” I say, converting between metric and standard.

“Some say that three feet of rise by 2100 is a ridiculous exaggeration, but the long-term record says that’s pretty average; says sea level steadiness is the exception, not the rule,” Rob responds. Then he leans back in his green upholstered chair. Together we talk about how what happened in Antarctica—or, more precisely, what didn’t happen: ice sheet withdrawal—influenced our history well before humans made direct physical contact with the last continent.

“Antarctica’s stability might have been related to the importance of port cities, international marine trade, and the spread of settler colonialism,” I venture. “If sea levels were rising three feet a century while Europeans were ‘discovering’ the Americas, things might have worked out differently.” The difficulty of establishing colonies and transporting enslaved people across the Atlantic might have led to a present with more bowhead whales, a present where the cost of combusting crude, among other things, would be higher. The distance between us and a livable future not so vast. The longer we talk, the clearer it becomes that the entire cryosphere—the two hundred thousand glaciers that weave among the world’s highest peaks in the Himalayas and among the mighty basalt bowls of Patagonia, the ice sheets and all the other parts of the Earth where water is locked in cold suspension—dictates many aspects of our lives. That the geologist sitting before me agrees is a revelation, freeing me somewhat from the uncomfortable feeling that I’m just trying to take an Indigenous perspective from the other pole and use it to project what I wish to see onto the ice.

It takes the Palmer nearly two weeks to finally nose into the ice. Just north of the Antarctic mainland we spend a couple days digging for ancient penguin bones on a remote island chain and then an eleven-day medical evacuation sends us to Rothera Station, up on the Peninsula. By the time we finally reach Thwaites, my shipmates and I have been at sea for nearly a month.

On the morning of our arrival, I run up to the bridge to watch Thwaites come into view. Out in the gathering light its gray margin wobbles in the gloaming. No one knows quite what to say. The words I conjure—cirque, serac, cleft, torque, ski slope, rampart—all slide off the surface of the ice, plopping one after the other into the bay right in front of Thwaites; a bay that had up until just a few weeks prior to our arrival been perennially covered in ice. I hadn’t imagined how profoundly apart this place would feel—how it would appear gigantic and fully formed, an entity all its own, well beyond the limits of human understanding and resistant to whatever language I might try to pin on it. I try out different words for white—plaster of Paris, opalescent, pearl—and blue—cobalt, cadmium, torqued turquoise—but none get at the way these colors come together to form a symphony of sorts, a polyphony of light and play, impossible to translate. Afterall, this floating ice shelf is comprised of snow that dropped before the rise and fall of Rome, before Jesus or the Buddha were born, before the invention of the alphabet. Before sound became symbol.

We, who have been at sea for so long, finally gaze upon the glacier that has already given us something spectacular: friendship, a faith in one another. Rick, the first mate, who in the past couple of weeks has gone from stranger to pseudo-dad, stands attentive at the ship’s helm, the captain next to him, steering us along the edges of Thwaites’s unfathomable fracturing, its hemorrhaging heart of milk.

According to the New Oxford American Dictionary, “to calve” means to give birth to a baby cow or to split and shed a smaller mass of ice. These definitions—of animals and of glaciers both—describe the moment one thing becomes two. From cleaving, a flourishing, some new start. This linguistic echo has long delighted me, because it helped me think of Antarctica not as an inhospitable island at the bottom of the Earth, but as a mother, a being powerful enough to bring new life into the world. However, the idea that Antarctica’s great glaciers are responding to us, to our actions thousands of miles away—by calving bergs whose very bodies bear grave warnings, urging us towards new ways of living with one another and the Earth—seems somehow wrong. Or not wrong exactly, but too easy an interpretation of what the ice might be saying.

At some point, I sprint to the galley, scarf down two hard-boiled eggs and half a cinnamon bun, and run back up, taking the stairs two at a time. Soon I am outside again, attempting to honor the ice by looking away as little as possible. Thwaites’s calving edge stretches over a hundred miles, and so it takes us hours to travel its length. Sometimes the margin appears steep and sturdy and sheer; in other places it loses its sheen, seems chalky and distressed. We turn a corner and the face rockets upward into a wall. A wild line twists along the top of the shelf, tracing gorges into the blue-white snow. Then, just as abruptly, the parapet has crumbled, cluttering the water with floating pieces of brash.

An emperor penguin dives off a nearby floe; begins porpoising in and out of the water. It draws closer, turning, I imagine, to look at the ship. What about us registers as novel to it? Our size? Our speed? The sounds and smells we emit? The white of the bird’s underbelly flashes teal through the Southern Ocean’s stained glass. Then the graceful creature pulls away from the bow and, after a few long seconds, soars out of the water. The flame on its long neck a stamp of light.

Gui, a marine mammal expert, and Joee, a marine technician, join me out on the bridge wings. She’s wearing green Carhartts and a black thermal shirt, while he’s bundled up in a puffy winter jacket, a wool scarf, and a beanie. Of all the people onboard, they are the two with whom I feel closest, and yet I don’t think we three have ever spoken together alone. For a while, we whisper about the fog clinging in dense pools where the ice meets the water, and also about how underdressed the woman from Maine appears compared to the guy who studied whales in northeastern Brazil.

“It seems fitting to me that Thwaites is unwilling to yield her secrets, that everything is shrouded in mist,” Joee says. “At this basic level, we really don’t know what we’re looking at.”

“This morning, as I took pictures, I felt a little like I was—I don’t know—stealing,” I say. “Like, who am I to take a picture of this place?”

“That big block looks like it could fall any second,” Gui says. Then he purses his lips and blows in a mock attempt to make it tumble.

“Maybe if we holler at it,” Joee suggests.

We let out a series of yips and growls, each of which returns as an echo hollowed out by the ice.

We are running close now, with only a hundred yards or so between us and Thwaites. The sea still. Its mercurial surface reflecting the glacier’s damaged face. Our whoops turn to laughter and then silence. Because nothing we do or say matches what stares back at us, the deceptive calm we can’t digest.

“I just stood outside all morning, staring at everything,” Gui says, mercifully breaking the silence. “All the time I was thinking, What is all this? Sometimes I was thinking, How long is it going to be like this? And, always, What is my part in pushing this system to this point, like, what the fuck are we doing?”

Tasha, the media coordinator, comes over. “Try not to take any photos with the smokestacks in them,” she says. Behind her a tendril of gray vapor unfurls in the otherwise cotton-colored sky.

“That can’t possibly be from us,” Gui says. He squints into the distance. “Oh yes,” he adds, shakes his head. “Yes, it is.”

Tasha leaves, and we do what she asked us not to.

What I wouldn’t give for Thwaites to not be breaking, for the expedition to not be here at all. But here is where we have arrived, after so much effort.

If I am being honest, most of the ten days we would spend alongside Thwaites I am inside the Palmer. Sure, I trapse up to the bridge to watch the ice from time to time. But more often I work on the second-to-lowest deck onboard—the one that sits right at the waterline—digging sediment out of a three-meter-long tube, or interviewing my shipmates, or transcribing those interviews. Our task is simple: gather as much information as humanly possible from this place on the planet that no humans have ever visited, before the ocean freezes back over.

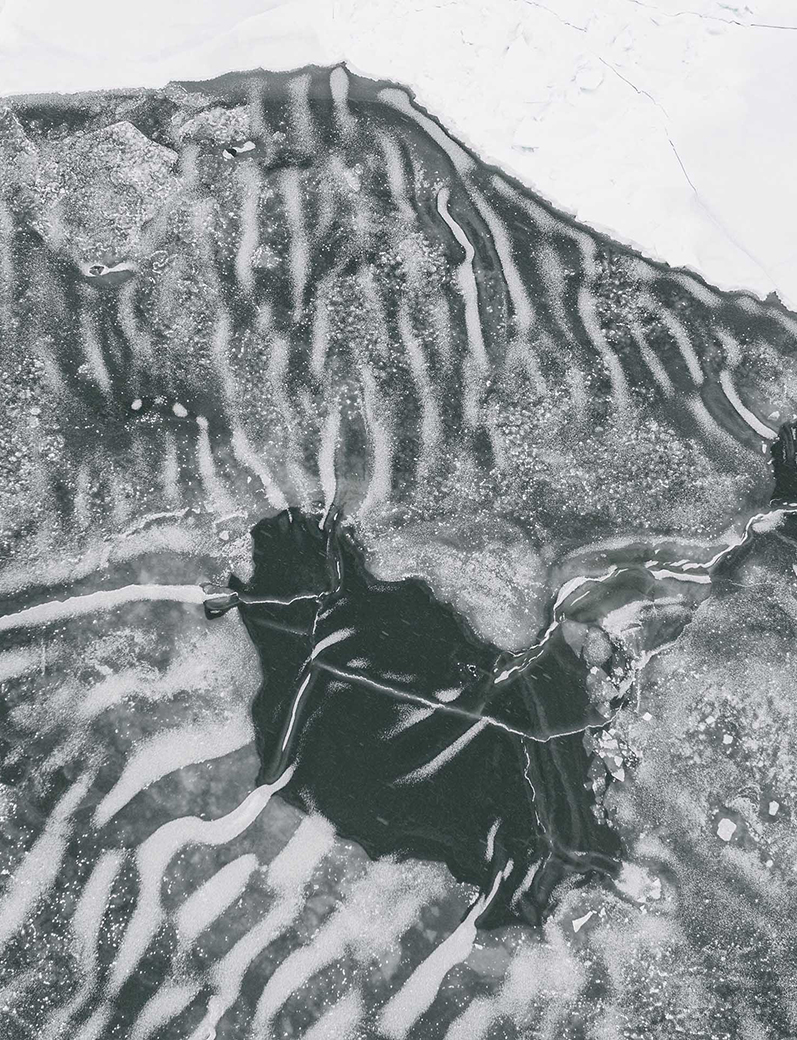

Nearly a week after our arrival, a slab of Thwaites’s ice shelf (twenty-five miles wide and fifteen miles deep) collapses. The catch: we don’t really know that it is happening until aerial satellite images of our study area finally make their way onboard. In the image taken on our first morning, Thwaites’s western edge appears relatively sturdy, a long white rampart running along the innermost reaches of the nameless bay in which we now sail. In the second image, taken just days later, it appears as though some belligerent teenager has taken a baseball bat to a windshield, causing that same ice to break into hundreds of pieces.

When I see those satellite images, I run to the bridge to try to bear witness to what is apparently happening all around us. I step outside and walk behind the Palmer’s smokestack to get out of the wind. The low-grade hum of the churning diesel engine mumbles in my bones. There I search my memory for signs of collapse, for some marker of change, anything dramatic. But nothing really springs to mind. The wind thrums in short guttural gusts around the hull. The day is bright, the bay cluttered with bergs or so it seems; it’s hard to say what exactly is happening since, really, I only just arrived. I have made it so far, and now I want—no, I need—to be able to recognize the glacier’s movements as its own, its fracturing as a willed response to what we have done to the planet. When a glacier steps back or surges in the Arctic, those who live with the ice say it is sending a message. For as long as I have known Thwaites’s name, I imagined receiving that message, that this moment of its breaking would ring through my body as warning. But I never considered the possibility that the cracks would be so large I wouldn’t know they were cracks. That its movements, even when viewed up close, would seem static. That I would not be able to distinguish berg from shelf, something whole from something broken.

I never considered that collapse could appear so still.

I thought that by going on this journey, by drawing closer to the source of so much change, I would become a better medium, a more perfectly tuned instrument, a conduit through which these transformations might manifest, that they might pass through my body into language. But whatever message Thwaites is sending, it is far more layered, more complex and full of subtle meanings, than those which I have projected onto it from afar. The week I have spent alongside Thwaites is, after all, nothing more than a teeny tiny blip in glacial time.

I can count on my fingers the number of days I have spent alongside this ice. I can count the number of hours I have been under its spell. In the funnels’ familiar slipstream, I try a while longer to see the extraordinary event unfolding all around us, but whatever bolt of enlightenment I hope for does not arrive.

I never considered that collapse could appear so still.

In environmental circles, speaking of the agency of the more-than-human world is increasingly something we do. It is a part of a larger effort to make this whole conversation—long ruled by well-heeled whites—more democratic. To incorporate the voices of the plants and animals and rocks that capitalism treats as resources to be extracted. And it is also a necessity, driven by the fact that climate change has come home to roost. It is hard not to recognize the agency of water when a thirteen-foot storm surge spills over the berm and rips dozens of homes from their foundations, as happened in Staten Island during Sandy; or when fifty inches of rain fall in Houston, turning golf courses, thoughtlessly plopped on top of wetlands, back into sanctuaries for breeding birds; or when the Schuylkill River turns into a raging torrent that eats many of Philadelphia’s major highways, as happened in the aftermath of Hurricane Ida in 2021. If, in our headlong rush towards increasing comfort, we have lost track of the fact that our existence on this Earth is always unfolding in conversation with it, then we are certainly being reminded of the depth of this dialogical experience now.

And yet, and yet.

I traveled towards Thwaites, giddy almost with the idea that I would be able to cross the Southern Ocean and immediately turn my ear to the ice and perceive what it wished to communicate. How was it that I imagined the ice whispering something directly into my ear? It seems almost laughable now that I have returned home. Of course, my desire to listen to Thwaites, to recognize it’s animacy, did not immediately translate into an ability to do so. Time, above all else, would have helped me achieve my goal, and time is one of the few things we have very little of.

Something I have been thinking about a lot lately: in order for the stories we tell to recognize life in all beings—seen and unseen, seemingly inert and otherwise—we have to dwell in place long enough to notice when change is afoot. That is, long enough for landscapes themselves to transform, long enough for those (often) more subtle movements to manifest and cause societal shifts that are as seemingly imperceptible as they are strong. Time—great lengths of it, ribbons, reams, centuries, millennia, unfolding—is part of what makes it possible for the Tlingit, for instance, to listen to the ice and craft narratives that replicate some of the mystery of its movements.

It is impossible to short-circuit time. Impossible to cheat your way towards more of it. I tell my writing students that in order to write something compelling, you show up time and time again. Good writing, transformative writing, is not about innate talent; it’s about labor, about a temporal investment in the work. Mothering is similar. When I think about how to translate this knowledge to the question of how to recognize the animacy of the more-than-human world, the answer is simple enough: start close to home. Forget the quest towards the sublime mountaintop. Start with the earthworms in the backyard. Start with the soil where we attempt to throw down our wobbly roots. Pay attention to the place where our lives unfold. Where time, lots of it, is at least partially, a given. Here, right here, is where we begin to recognize the Earth as alive.

Adapted from The Quickening: Creation and Community at the Ends of the Earth

Atlas with Shifting Edges

Elizabeth Rush reflects on climate change as a transformational force on our landscapes and the words we might use to grasp this shifting reality.