Anna Badkhen is the author of seven books, most recently Bright Unbearable Reality, which was longlisted for the 2022 National Book Award and for the 2023 Jan Michalski Prize for Literature. Her awards include the Guggenheim Fellowship, the Barry Lopez Visiting Writer in Ethics and Community Fellowship, and the Joel R. Seldin Award from Psychologists for Social Responsibility for writing about civilians in war zones. Her essays have appeared in New York Review of Books, Granta, Harper’s, The Paris Review, Orion, and The New York Times. Anna was born in the Soviet Union and is a US citizen.

Alexander Bee is a photojournalist who was born in India and grew up in a coastal city of Normandy. Since working for the United Nations agency for Migration in Mauritania, Burkina Faso, and Djibouti, he has developed a passion for documentary photography. Strongly humanitarian, his work focuses on contemporary social issues.

When does a journey begin? Anna Badkhen considers failed migrations and the impossibility of escape as the forces of climate catastrophe and colonial greed combine to trap the world’s most vulnerable populations.

He didn’t catch the name of the Saudi town where he was headed, where he had hoped to find work in a foundry. Then again, he never did reach it.

First, he said, the smugglers beat him where he clung to the bulwarks of their open fishing boat. They ordered him and the other passengers to spit out the balance of the smuggling fee for their illicit voyage across the Gulf of Aden, $1,400 a head—$1,400 his whole family had raised over several meager harvests of tomatoes and sorghum and teff—or else they would be made fodder for the heavy stacked waves that mawed and slobbered at the boat over the five-hour passage across the toppling seas. Then they threshed out the pitiable viaticum he had saved for the journey. At last, he and the other seasick travelers slammed ashore in Yemen and boarded the trucks that drove them across the desert to Saudi Arabia. But hardly had they crossed the border when Saudi border guards rounded them up and crammed them into an airplane that deported them back to Ethiopia. His entire journey—from his swallow’s-nest village in Amhara, above the Afar Triangle, an arid boneyard where man was born; eastward to Bosaso, an ancient capital of cinnamon trade and now of human trafficking; across the Gulf of Aden, the world’s busiest maritime migration route; across Yemen to Saudi Arabia; to Addis Ababa—took less than a week.

Seven months later, the ill-starred voyager was back by the side of Ethiopia’s Highway 2, the north-to-south road that scaffolds the western rim of Afar. From the highway’s west shoulder, wooded scarps clawed at infinite low cloud. From the east shoulder, mid-March fallow fields, cleft pink by seismic fissures, tumbled to parched scrublands deep below. He was not alone on the road. For miles along Highway 2, nearly at each roadside hamlet, unmarked bus stops scalloped clearings out of eucalyptus forest for young men to strand together like flotsam under giant billboards that proclaimed, “Let us stop our children from dangerous migration,” and “Illegal human trafficking will cost us the workforce of our youth,” and “No man should be exposed to wild beasts or human traffickers.”

Waiting for what here? A bus. A sign. Tailwind. The unmarked flag stops made of this road shoulder a kind of arcade, made of the road a temple, Our Mother of the Unmoored, and it was difficult to say whether the men who loitered there, on the western edge of the Great Rift, had already gone a ways on their journey or if they were just setting out. But who can really tell when a journey begins?

When does A journey begin? When droughts parch the land, or mudslides take entire farms and crash them into ravines, or floods drown the crops? When herds dwindle, or fish leave for colder seas, or extraction poisons the wells? When war breaks out over resources, when political unraveling echoes the steady and inexorable deterioration of the home ground itself?

The regulatory vocabulary that international relief agencies use for assessments and calls to action describes climate migration as “the movement of a person or groups of persons who, predominantly for reasons of sudden or progressive change in the environment due to climate change, are obliged to leave their habitual place of residence, or choose to do so, either temporarily or permanently, within a State or across an international border.” Relief agencies seem to have a term for nearly every state of human condition in extremis; they even have terms for terms. For instance, “Integrated Food Security Phase Classification” (IPC) is a name for the five-phase scale that describes the severity of food emergencies, ranging from Phase 1, “minimal,” to Phase 5, “famine,” which IPC defines as “the absolute inaccessibility of food to an entire population or sub-group of a population, potentially causing death in the short term.” Alex de Waal, executive director of the World Peace Foundation, an affiliate of the Fletcher School at Tufts University, has pointed out that “by using the term ‘famine’ to describe nothing less than an absolute state of food insecurity, the IPC classification system has had the unintended effect of implying that anything short of it is acceptable.” Assigning bureaucratic value, as ever, devalues the dreadfulness of the thing.

Climate change, experts say, is the primary cause of human migration on Earth. And so it is in the highland villages and towns along Highway 2, in the rafters of the world, where people have grown things for thousands of years and still do, and still rely for the most part on their increasingly unreliable harvests; where arable land is rapidly ceding to unpredictable weather patterns, drought, deforestation for biomass fuels, erosion, or heedless development, often by outside powers; where poverty grinds so much human ambition to barren dust.

The Afar triangle harrows the Earth halfway between Beqaa Valley and Mozambique, the endpoints of the Great Rift Valley, a series of depressions that rent the planet’s shell thirty million years ago. The East African Rift, which includes Afar, is one of these depressions.

“Rift”—a split, an act of splitting—came into the English language from the Old Norse ripa, to break a contract, in the early fourteenth century. Since the 1600s, it has been used in its figurative sense. In 1921, geologists incorporated it as a term for a place where the Earth’s crust and upper mantle are being pulled apart. They call it “extensional tectonics.”

In either meaning, a rift is when or where things fall apart, come asunder. Afar is the southern rifting arm of what geologists call the Afar Triple Junction, a pulling apart of three tectonic plates near the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden; a pulling apart that continues still, slowly dragging Africa away from Asia, slowly stretching the valley’s girth. Step to the western edge of Highway 2 and peek over the brow of the Ethiopian Plateau that hugs Afar: the jagged pink trenches that gash the fields of barley and sorghum and teff are the recent stretchmarks where the Earth has yawned.

Fossils of the first of the human clade were found here, as well as the remains of some of our earliest Homo sapiens ancestors. This is where we began to form a relationship with place and change, and the notion of the sacred. This is where we adapted and adapted until here we were. Is it any wonder that ours is a history of leave-takings, of estrangement? These pale schismatic hillocks of our beginnings are our very first port of departure.

Who determines whether a journey is possible? The concept of “trapped populations” entered the mainstream vocabulary of environmental migration experts after appearing in a 2011 policy document. According to the International Organization for Migration, the term describes people “who do not migrate, yet are situated in areas under threat, […] at risk of becoming ‘trapped’ or having to stay behind, where they will be more vulnerable to environmental shocks and impoverishment.” The UN Environmental Migration Portal adds that “in the context of climate change, some populations might not be able to move due [to] lack of resources, disability or social reasons (e.g., gender issues), and other[s] might choose not to move due [to] cultural reasons, such as the ancestral links people have with their land.” Might not be able to or might choose not to: how uncharacteristically vague for NGO-speak; how definition washes out into the indefinite, undefinable, actually and acutely human.

It is impossible to estimate how many people fit the description of “trapped populations,” writes the International Organization for Migration. “They are highly vulnerable populations, but data to inform action and protection are scarce”—though the World Bank by some means has calculated that by 2050 “trapped populations” will number 140 million people.

Note the adjectival construct “trapped.” Linguists call such constructs false passives, or stative or static passives, or resultative passives. “Trapped” represents a result, but it conceals the cause, obscures the continuing fault that is creating both the climate catastrophe from which people might need to (and might not be able to, or might choose not to) migrate, and the conditions that prevent them from doing so, that force them to be static. It does not address the unabating gap between the mostly white power structures that generate and foster and exacerbate climate inequality and the mostly poor, mostly Black and Brown communities that bear its brunt.

One policy paper I read warned that “trapped populations” was a label that “may reduce or remove an individual’s agency and independence in determining their own destiny.” (Another term relief organizations use to describe people who cannot, or do not, leave environments imperiled by climate change is “climate hostages.”) But it is the racist world order, which centers and upholds extractive industries and largely temperate-climate powers, that really does most of the determining. Scientists predict that almost one-fifth of our planet will be unlivable by 2070, at which time, unless they will have moved by then, 3.5 billion people—half of the world’s population today—will live in the unlivable zone. And why would they not have moved? “Trapped populations”: the term ignores the cognitive rift between the axiom that migration is a primary form of climate adaptation and the actuality that most destination geographies for migrants are responsible for the unfolding climate catastrophe and do all they can to keep out the people whose lives they have imperiled: they are doing the trapping.

The journey begins or doesn’t begin long before the land no longer yields or the climate becomes unlivable.

Sometimes the journey doesn’t begin at all, or it begins and is aborted, botched, cut short. In the summer of 2020, early in the COVID-19 pandemic, IOM estimated that nearly three million migrants were stranded at borders, in concentration camps, along migration routes, or with expired visas and work permits, often without financial or legal means to sustain themselves.

It’s early March, 2022, and Russian troops are shelling the humanitarian corridors Russia itself had designated for safe passage of civilians out of Ukraine. A photographer snaps a shot: a man with a rucksack is walking with determination past four people sprawled on the asphalt: a man, a child strapped into a school backpack, another child—his torso on the sidewalk, his legs on the road—next to a rolling duffel bag. Cradling a small case, the woman almost looks asleep. The walking man: will he make it out alive? Europe readies to receive millions of people expected to flee Ukraine in what the UN calls “the fastest growing refugee crisis since World War II”; across the continent and beyond, people and institutions are collecting blankets and food. Families prepare to host refugees in their homes. But foreigners from Africa and South Asia who try to evacuate from Ukraine are often detained at the border and pulled off transport that would carry them out of the war zone.

On a damp, cool week in March of 2020, two colleagues and I drove north on Highway 2, pulling over every so often at flag stops where young men congregated with their cheap smokes and crotch funk and fernweh. First stop: Sulula.

“Good morning!”

Thumbs up.

“Do you speak English?”

“If I spoke English, I wouldn’t be here.”

“Where would you be?”

“America!”

“How would you get there? Would you go by boat?”

“No, that’s not the proper way to leave.”

“Don’t listen to him, he’s just talking. Everyone knows that it’s the only way to leave.”

“Do you know anyone who left this way?”

“Yes, two people.”

“Are they okay?”

“We think so.”

“Why do people leave here?”

“Look at us. What we eat is what we earn. Odd jobs only.”

A minibus pulled up.

“Tell you the truth, we are planning to leave come Ramadan.”

“Safe journey.”

A wave.

On to Hayq, named after a mountain lake that is steadily drying because of deforestation and climate change; Alet; T’is Aba Lima. Men perched on precipices and passed around small oranges and puffed barley, and more and more flocked to the conversation and poured the grain into their palms like birdseed—then spilled the spiced kernels as they traced with agitated fingers the compass roses of escape: Adams in the garden, naming things. Their frenzied needle arms dashed between the weary fields of home and the imagined tinsels of faraway happiness, diagrammed the escape they wished to prize from this beautiful everlasting land, their flight wingless, and for that, all the more precious. These two over there had sailed to Yemen and were deported; this one knew someone who went to Libya to cast for a Mediterranean boat; this one had two friends who must be in Saudi by now.

“Do you remember that kid from downcountry? He went to Sudan and then Libya and then Europe.”

“Yes, but we haven’t heard from him, we don’t know where he is now, if he’s made it or not.”

The exodus—via Sudan and Libya or, more commonly, via Djibouti or Somalia (the Land of Nod, east of Eden) and then across the Gulf of Aden to Yemen to Saudi Arabia, what migration experts call the Eastern Route—is one of the most massive international human movements on the planet. One might call it “Out of Africa 3.” The previous year, close to twelve thousand people crossed from the Horn of Africa to Yemen each month, despite the dangerous sea passage and despite the war, subsidized by the United States, that has killed more than 130,000 people in Yemen since it began in 2014. Three weeks after our encounter on Highway 2, a militia in Yemen opened fire on a caravan of Ethiopian migrants seeking passage through the desert and killed several dozen people; the militia then drove the survivors to the border with Saudi Arabia, where Saudi border guards shot more people and rounded up the rest into a concentration camp.

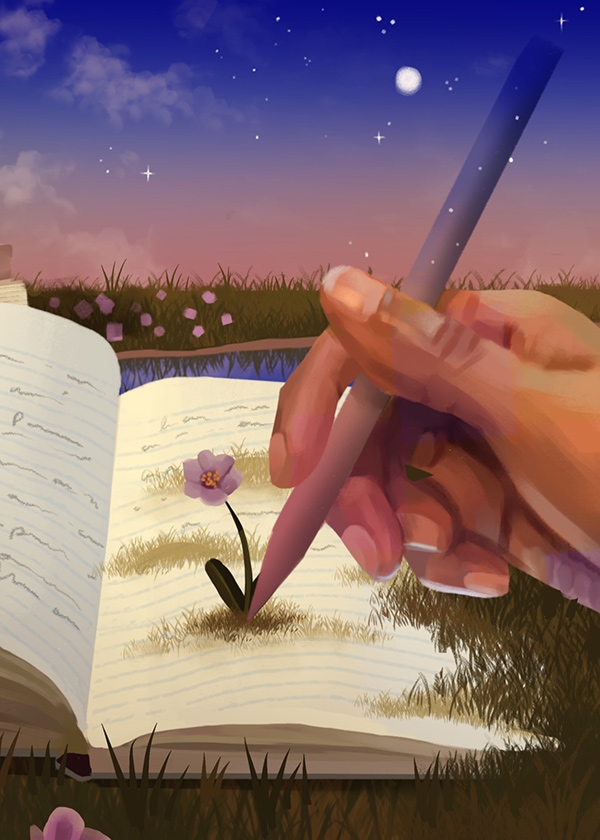

An Ethiopian migrant in Obock, Djibouti, waits to cross the Gulf of Aden toward Yemen.

Photo by Alexander Bee

A parable I heard a lot growing up:

There is a flood. Ankle-deep water at first, and folks are crowding into cars, but one pious old man tells his family to go on without him, for God will rescue him. All the people with cars leave, and the water is up to his waist now, when a neighbor offers the man a seat in her dinghy. The old man waves her off: God will rescue him. Now the water is up to his armpits. A search-and-rescue team makes a water landing in an amphibious helicopter, yells at him to get in, get in, for God’s sake, but he yells back that he will be fine, thank you very much, God will save him. Then he drowns.

You can probably guess where this goes from here: On the other side, the old man meets God and demands to know why God allowed him to die, and God, incredulous, responds, “But I sent help for you three times!” It is intended to be a story about missed opportunities. But that might be a false premise. What I want to know is, why was there a flood in the first place?

The journey begins or doesn’t begin long before the land no longer yields or the climate becomes unlivable. It begins or doesn’t begin with systemic exploitation of environments and their communities, with colonial greed that is centuries old and unceasing, that continues to rift our world.

Between July and September 2019, as the wannabe blacksmith sailed to Yemen in a smuggler’s boat and was deported back to Amhara, the government of Ethiopia performed the first IPC analysis to measure the prevalence of food insecurity in the country of 115 million people. The study found that 8 million people were in “crisis” (IPC Phase 3). A year later, war broke out in Tigray. Within months, thousands of people were killed, raped; more than 60,000 people fled from Tigray to Sudan, and 2.1 million more people were displaced from their homes but remained in the region. Ethiopian and Eritrean forces destroyed and looted households and food sources there. Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, winner of the Nobel Peace Prize, ordered Tigray blockaded to keep food aid from reaching the 6.5 million people trapped inside. Ahmed would later refer to these people as “rats.”

Several months after the civil war began, relief agencies somehow performed another IPC study, which found three million people to be in Phase 3, two million in Phase 4 (“emergency”), and 400,000 people in Phase 5 (“famine”), mostly in Tigray and the adjacent northern parts of Amhara. In plain English: almost half a million people were starving to death and millions more were on the brink, and no one was allowed in to help them, and they were not allowed to leave.

Geologists sometimes call the East African Rift by its acronym, EAR. Or—because it really is not one singular trench that slashes the continent north to south but several consecutive lacerations—they call it the East African Rift System, or EARS.

Hello? Hello? Can you hear this?

Before setting out from Addis Ababa northward along the lip of the Western Highlands, my colleagues and I met with Dr. Berhane Asfaw, the paleoanthropologist whose team discovered some of the oldest-known direct ancestors of modern humans—Homo sapiens idaltu, known commonly as the Herto Man—and the Paleolithic archaeologist Dr. Yonas Beyene, who discovered the world’s earliest Acheulean technology and its evolution. We talked about how human migration began sometime around two million years ago, when our early ancestors started using stone tools. A full million years went by before they domesticated fire. They probably had no concept of stars.

Skipping ahead a few hundred thousand years, Dr. Asfaw said, “You really wonder how the early humans got to Australia.”

“Yes, but we don’t know how many failed,” replied Dr. Beyene. “What percentage succeeded.”

The following day, we set off. We skirted Sululta, where several years earlier protests had erupted after Nestlé Waters had bought a majority stake in a bottled-water factory and proceeded to pump fifty thousand liters of water per hour, while local residents were left to travel on public transport to line up for water at a tap built by a Sudanese oil-and-gas company, or to collect water from a faucet provided by a Chinese tannery that had been accused of polluting water supplies. Just north of Debre Sina, we had to stop at the tail end of a day-old traffic jam. An eighteen-wheeler going to Djibouti had overturned into a steep crevasse on the east side of the highway, and the police had sealed off both lanes; on our side, northbound, the line of trucks and buses and cars stretched for miles, and shipwrecked travelers snacked on sugarcane and puffed barley on road shoulders that were by now a ronde-bosse of soda bottles and cigarette butts. Where was everybody headed? People shrugged, waved slack wrists: that way.

Some may have been going to Lalibela, a site of pilgrimage where a twelfth-century Ethiopian king hewed churches out of mountains, or to the ancient kingdom of Aksum, in northern Tigray, which within a year would become an epicenter of war and famine; some farther away, to Djibouti, to Sudan, to Yemen, beyond. But for now, everyone was just waiting. Young men hawked lukewarm water and soda; a matron walked uphill holding two orange chickens in one hand and an orange cat in another; truck drivers napped and smoked on the tarmac under their stalled rigs; a young mother scolded her exhausted toddler; an air-conditioned SUV with UN insignia zigzagged past the caravan, only to be sent back to the end of the line; a woman in a shimmering green jellabiya ducked into a parked blue-and-white tuktuk for shade: the whole of human movement—impatient, weary, hopeful, resigned—on display on the stretch of road. And then afternoon church bells broke forth on a rise still beyond our sight, and the alarmed clang bounced back from all the hills, and it was a Lenten Sunday.

Town: Wichale, where in 1889 colonial Italy tricked King Menelik II into signing the duplicitous trade treaty that precipitated Italy’s legendary defeat at Adwa. Clouds hemmed the perfumed slopes where they waited in the familiar uniform of itinerants, skinny jeans and damp hoodies drawn over faces fixed with resolve: to disclaim this land, to flee, they already had the tentative, slippery handgrip—the slip—their footing already lost or loosened; it was as if we’d encountered these Icaruses midflight. And they were midflight, watch. How they scanned the road for the bus that might take them away. How they hovered for hours under large billboards that diagrammed dreadful futures of migrants, faded lemming bodies crammed onto rafts and hurled facedown at foreign wrack lines, billboards made more frightening because children had stoned them for target practice, shredded them into exit-wound pennants, amplified their unblessed portent. How, now and then, these aspirants swaggered up to the eastern ledge where the shoulder plunges thousands of feet to the valley floor, and bent over—magnificent, dauntless funambulists—and aimed their expert spitballs all the way down to humankind’s cradle, which so many have departed before: take that! They talked with us shyly but with conviction about the crossing, but they did not wish to give us their names or to know ours, for we were of no use to them. They leaned instead on one another, in those boyful, sideway-draped embraces that are primed to turn any moment into bracing a wounded comrade from a fall, and right away I probably wouldn’t even have been able to tell the difference, the imperceptible buckling of the knees, the slightest shifting of the weight, the wing feathers suddenly unglued.

A buffalo weaver flashed a tangerine rump above the road, and some of us looked up. From the bird’s-eye view, all of us humans on Highway 2 must have appeared as roadside ephemera, our hopes unintelligible from above, unclassifiable. The silver mass of eucalyptus closed on the bird, and as we looked away from it, I met the gaze of the blacksmith. Maybe he anticipated my question, because he leaned toward me and swore that once he had raised enough money he would go back to Saudi and find a forge that would hire him, he was only sixteen, he had plenty of time to make something of himself, and his eyes were as lucid green as his mountain slopes, and as distant.