Jack Dash is an ecologist and writer based in Tucson, Arizona. He is vice president of the Arizona Native Plant Society in Tucson and co-creator of Atascosa Borderlands, a visual storytelling project combining botanical survey, oral history, and documentary photography to explore a notoriously rugged landscape straddling the US-Mexico border.

Luke Swenson is a documentary photographer and visual storyteller. He is a graduate of Pratt Institute’s BFA Photography program in Brooklyn, New York. He is co-creator of Atascosa Borderlands, a visual storytelling project combining botanical survey, oral history, and documentary photography to explore a notoriously rugged landscape straddling the US-Mexico border.

Ancient populations of silverleaf oak, saguaro, and sweet acacia inhabit the Atascosa Highlands with no sense that the land around them is divided between the US and Mexico. But as the border wall imposes a hard boundary, this island of biodiversity in the Sonoran Desert faces an increasingly fragmented future.

Since the 2016 election, the threat of border wall construction had been hanging over the Atascosa Highlands, located at the western edge of a string of isolated mountain ranges along the border between the US and Mexico. In May 2020, it was announced that a contract had been awarded for forty-two miles of border wall to be built straight across the imposing topography of the Highlands, and construction began soon thereafter. At $30 million per mile, this steel barrier through the Atascosas amounts to one of the most expensive fences in world history, cutting through one of the most ecologically rich regions on the planet.

When we began studying this region, we hoped our work would be a celebration of its biodiversity, but between climate change, overgrazing of livestock, and border wall construction, the work often feels like an elegy, as we try to piece together landscapes by their remnant fragments. In January 2021, border wall construction was paused pending government review, providing a unique opportunity to assess the effects of the wall on the ecosystems of the Highlands.

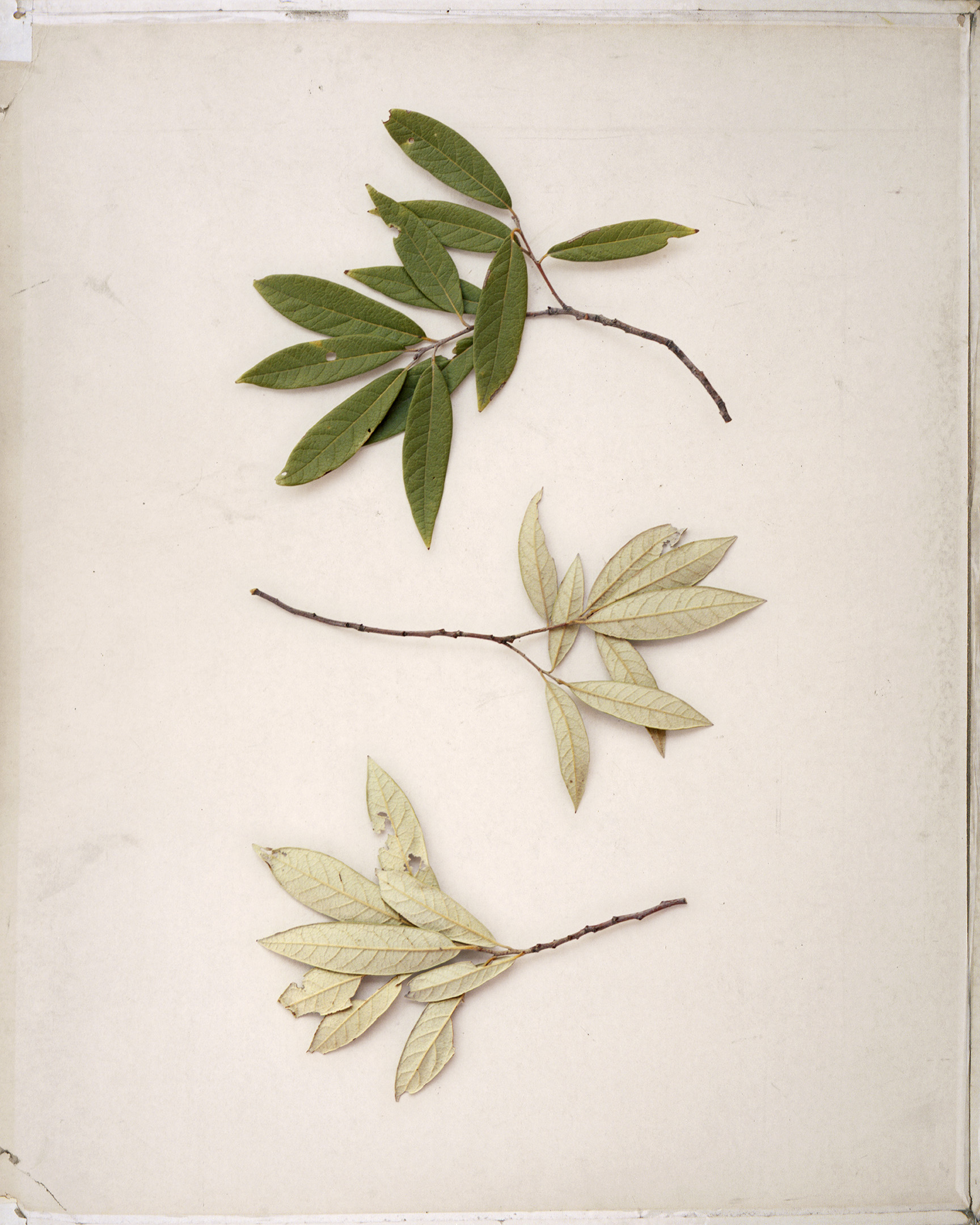

Silverleaf Oak

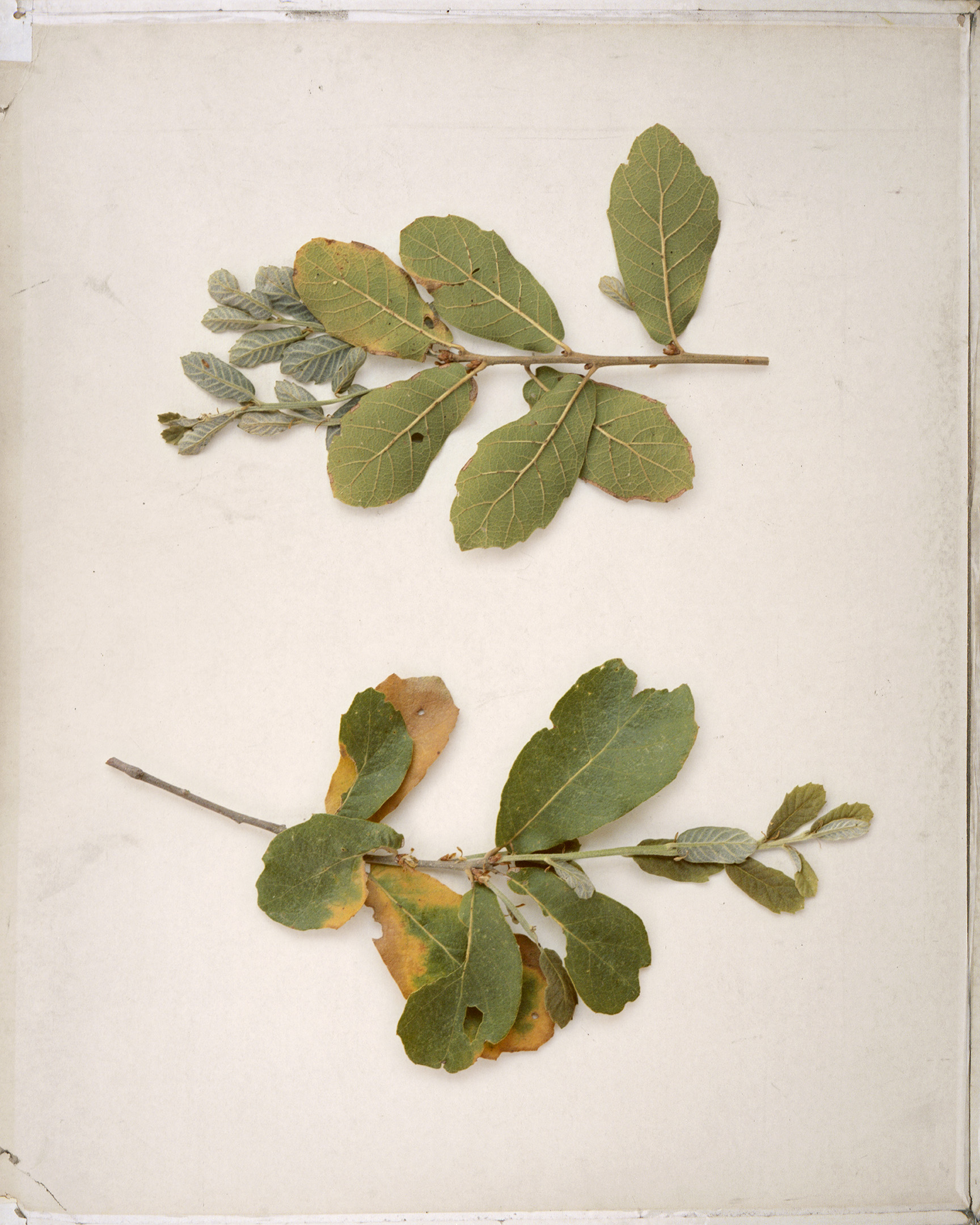

Silverleaf oak (Quercus hypoleucoides)

The silverleaf oak (Quercus hypoleucoides) inhabits the rugged mountains at the margins of the United States and Mexico. An easy-to-recognize species because of its teardrop-shaped leaves with undersides covered in tufts of white hair, silverleaf oak is typically found at higher elevations in shady woodlands. Near the border, deep in the Atascosa Highlands, stands a small, isolated grove, a holdover from a bygone epoch when a cooler, wetter climate encouraged these oaks to spread out and cover the nearby hills; but as the climate has warmed and dried, the hillsides have converted mostly to savannahs of grass and hardy mesquite trees.

The presence of this species on a north-facing slope surrounded by the rolling grassland of the Atascosa Highlands gives us a window into the ecological history of the US-Mexico boundary, before the first borders were drawn on maps of North America. The Atascosa Highlands link the subtropical Sierra Madre Occidental of Mexico with the temperate Rockies that cut south from Canada, placing them at the ecological crossroads of North America. Peaks in this region are often referred to as “Sky Islands” because of the way they rise from low, inhospitable basins and act as migratory stopovers for species passing between the Sonoran and Chihuahuan Deserts. The cool heights of these mountains act as refugia for species trying to stay ahead of warming temperatures, habitat loss, and desertification at lower elevations.

The Highlands are not the tallest or largest Sky Island complex, and heading south on Interstate 19 from Tucson, Arizona, to Nogales, Sonora, the Atascosas appear to be an unimpressive jumble of crags and ravines. Yet secreted away in these hills—where wild chile peppers, tangled passion vines, tropical lobelias, and towering cacti have been forged together by time into unique species assemblages—is an incredible treasure trove of plant life. Within these mountains are ecosystems world renowned for their biodiversity. For thousands of years, humans, animals, and plants have moved back and forth across the rugged hills of the Atascosas with no sense that the land is somehow divided. But in the last two centuries, through compounding historical, geographical, and political circumstances, the Atascosa Highlands have been split in two by the international boundary line now separating Mexico and the United States.

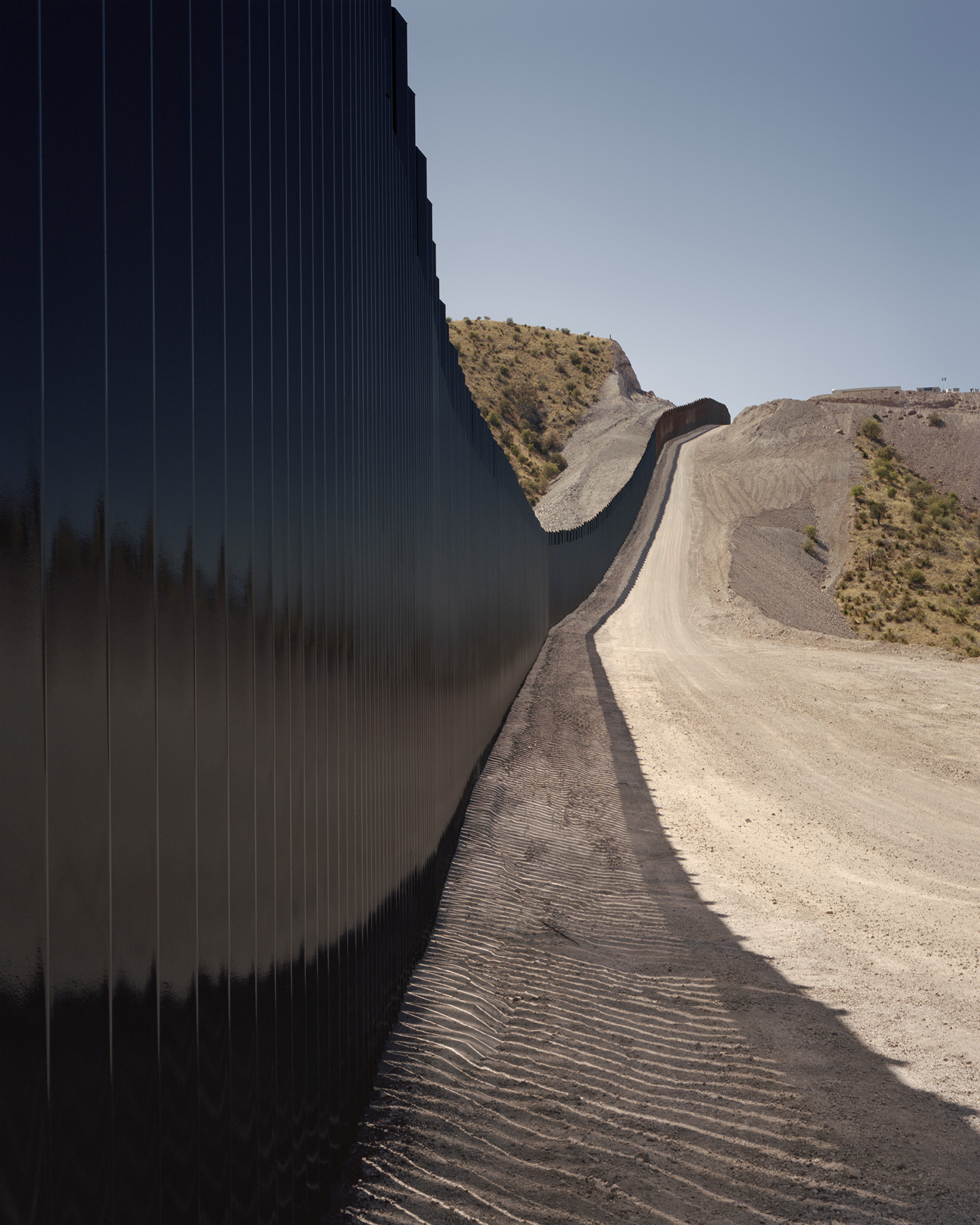

Newly built sections of the border wall near USFS Road 222

Over the course of a few decades, the US-Mexico border has transformed from a line on a map marked by little more than piles of stones to one of the most militarized boundaries on the planet, monitored by a complex web of surveillance technologies and an army of agents, and backed by a labyrinthine bureaucracy. Out of this apparatus sprouted the wall, a thin steel line, the sharp angles of its steel bollard panels contrasting with the organic curves and sweeps of the land it cuts across.

The silverleaf oak on this hillside—and the other small patches of oaks that dot the Atascosas—hold the genetic memory of millennia, and they have been witness to the changes these mountains have undergone in the past year. These trees saw the first surveyors arrive, superimposing straight lines on the sinuous landscape. They trembled as detonations rocked the hillsides, flinging dust into the air that alighted on their thin leaves, turning them sickly shades of yellow and brown and suffocating them under fine particles. The oaks sheltered the plants below them as bulldozers sent sharp, loose rock crashing down the hillside, burying their trunks in boulders glinting with flecks of mica.

For thousands of years, these oaks maintained a fluctuating and sometimes troubled equilibrium as ice sheets receded, temperatures rose, and new species were introduced to the landscape; despite these challenges they persisted. But as construction crews tear up the hillside around them to make way for a border wall, their future is increasingly uncertain.

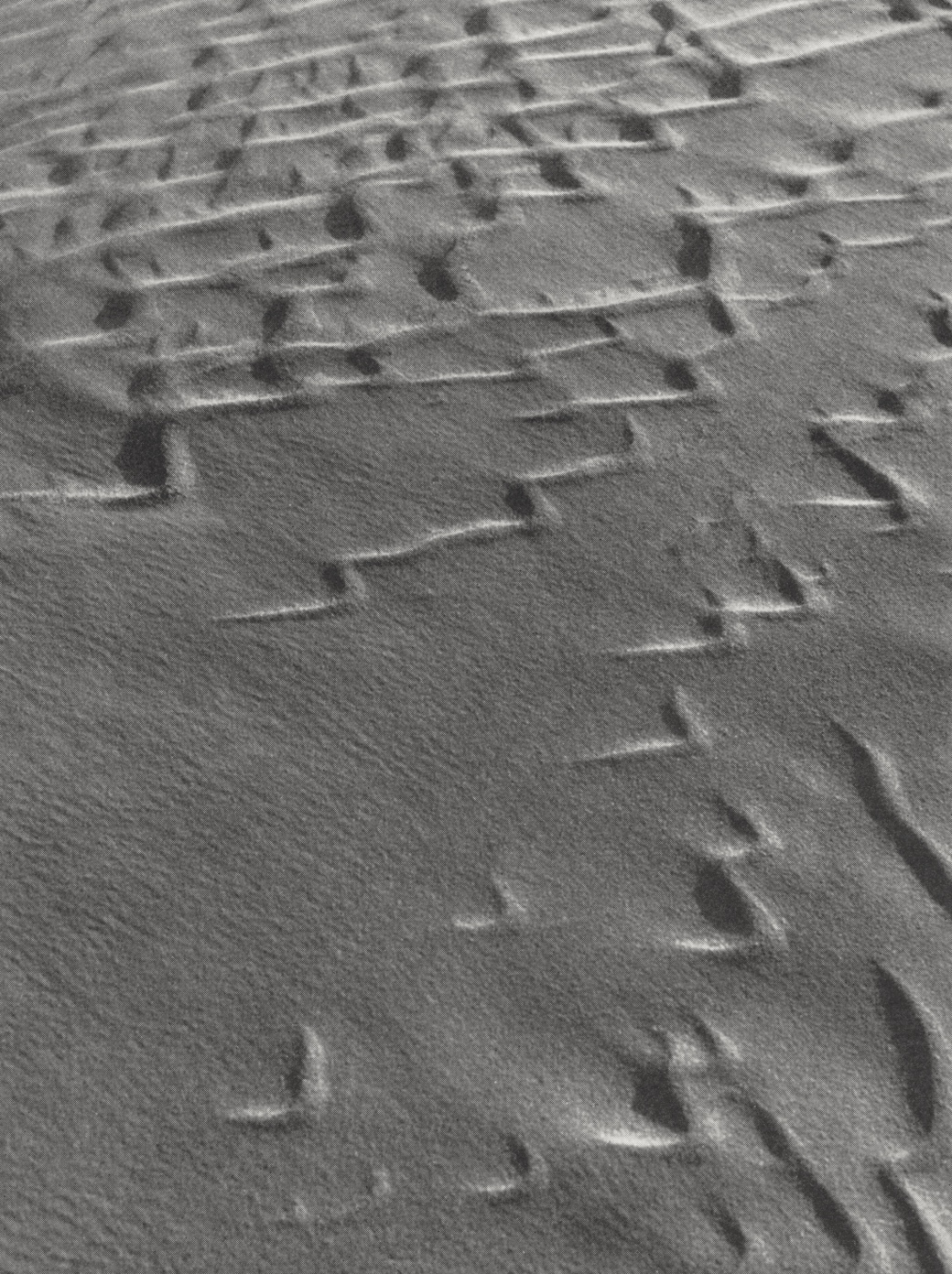

Unnamed access road near USFS Road 222 used for border wall construction

Gaping open pit mines, water-hungry nut orchards, and sprawling subdivisions line Interstate 19 before the exit onto Ruby Road—a former mining route that heads west into the heart of the Highlands. A spur called Triple 2 splits off from Ruby and heads south. This forest road has been transformed over the last year from a rough hunting track to a thoroughfare wide enough for the passage of sixty-ton machines. During active construction, tanker trucks drove up and down these hills spraying millions of gallons of water onto the roads to compact them, turning the desert into pavement. Shrubs along the side of these roads wilt, their roots hanging like cut wires, exposed after the ground beneath them was shaved away by passing bulldozers. As the border gets closer, the plants go from green to blue to gray under a heavy coating of dust.

A thousand feet above the valley floor, a fleet of machines sits motionless. Dump trucks, road sprayers, fork lifts, bulldozers, and backhoes are stored on the remains of a deconstructed mountaintop turned into a sprawling parking lot along the border in case word comes down from the federal government to resume construction. Last year the cacophony of heavy industry echoed between hillsides, punctuated by the crash of steel panels being set into the ground. Today the only sound is the wind rustling the dry grasses.

Unfinished section of the border wall

Emory’s oak (Quercus emoryi) stands along the rubble zone created by the border wall

The border is accessible by stepping off the wide access road and moving through one of the myriad canyons which have worn themselves into the landscape. Once every few years, rushing water rips through these narrow passages and cuts a little deeper into the earth. Now that process is reversing, and the channel is beginning to fill in with sediments washed down from hilltops shattered by wall construction. The Atascosa Highlands are in the midst of a historic drought, but even the few meager rains over the last year have been effective in loosening the finer sediments out of the rubble piles lining the new sections of border wall and carrying them into the arroyo bed.

The canyon dead ends at an imposing rubble flow that has covered and crushed almost all plants. Lifeless trunks jut from the stone like the masts of sunken ships. Islands of oak and manzanita are surrounded by oceans of dust and stone. Gnarled branches snag trash blown down from the construction site. Soda cans, paperwork, wrappers, and the Tyvek suits worn by paint crews litter the hillside.

On the other side of the rubble field stands the wall. The structure consists of thirty-foot-tall by nine-foot-wide panels made of rectangular steel bollards, sunk into the earth in a matrix of concrete and rebar. In most places along the border, the structure stands unadorned, its steel panels oxidizing in the desert sun. But here the panels have been coated in jet-black, high-gloss spray paint, splatters of which are evident on the exposed stone and dust-covered plants that cling to sheer cliff faces carved by explosives and heavy machinery. Like a carnival house of mirrors, the obsidian-black panels reflect a distorted and shifting image of the undulating hills of oak and grass. The road carved out of the grassland extends for miles in either direction, a fresh wound stretching out into the distance.

On the roadside near the steel panels, the seed head of a sturdy bunchgrass bobs in the wind. Most of the native grasses remain tan and dormant until the summer rains, but this plant is green and active in early spring. This is Lehmann lovegrass (Eragrostis lehmanniana).

Lehmann Lovegrass

Lehmann lovegrass (Eragrostis lehmanniana)

Historically, in a pattern repeated over centuries, small fires have swept the grasslands of the Atascosas approximately once a decade. These burns could be caused by lighting, or by the diligent landscape management of Indigenous peoples such as the Tohono O’odham, who still call this region home. It was these fires which kept woody shrubs from taking over the range, maintaining an unbroken sea of grass brimming with life.

In the 1800s these verdant plains drew Mexican and American homesteaders, and with the settlers came cows. At first, the cattle thrived on luxurious and seemingly infinite grass, but the success of early ranching operations and the influx of new immigrants lured to the area by promoters led to ever growing numbers of cows vying for increasingly limited forage and exerting an incredible pressure on the land. When drought hit in the 1890s and the ranching bubble popped, an estimated 50–75 percent of cattle in southern Arizona died or had to be shipped out of state. The cows stripped every bit of vegetation they could reach in an effort to survive, and grasslands that had been maintained for generations turned into sparsely vegetated wastelands. The effects of overgrazing were still evident in the 1930s as the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl gripped the West. Accelerated erosion, channel cutting, and dried up soil left the formerly fertile landscape largely barren, apart from stunted mesquite trees. Range managers were failing to stem the downward spiral of these ecosystems despite their efforts to restore native species, so they began experimenting with the idea of introducing exotic plants to take the place of the absent natives.

Invasive grass species: Lehmann lovegrass (Eragrostis lehmanniana), natal grass (Melinis repens), and buffelgrass (Pennisetum ciliare)

An introduced species doesn’t become rampant overnight. Like a wildfire, the spread begins with a spark and grows in fits and starts; there are few better representatives of this pattern than Lehmann lovegrass. This much maligned species, which originated in the Kalahari Desert, was initially introduced to the US from South Africa in 1932, courtesy of the pioneering female botanist Maria Wilman, who hoped that it might help scientists revegetate the rapidly degrading rangelands of the southwestern United States. In 1935, research trials funded by the US Department of Agriculture were underway, attempting to identify particularly good cultivars for the dry grasslands of Arizona. One accession showed promise for its fast growth and rapid development of viable seed; it was given the dry and unassuming name of “A-68.” This selection became the progenitor of one of southern Arizona’s most pernicious weeds. Since the late 1930s, range managers, ranchers, and highway departments have broadcast thousands of pounds of seed across Arizona. The grass spread slowly, patch by patch, until a succession of wet years in the early ’80s precipitated a sudden explosion in numbers of this species. Free from the checks and balances of its natural range, lovegrass began laying claim to huge swaths of the borderlands. By 1988 an estimated 170,000 acres had been intentionally seeded, but already lovegrass was thought to occur on at least 347,000 acres, displacing and smothering remnant stands of native grassland.

This is not an uncommon story. Over the last few centuries, plant species from every part of the world have been caught up in the chaotic flow of globalization and deposited intentionally, or not, into new ranges, where many have thrived and expanded. Most of the invasive grasses reviled and targeted for destruction by conservationists and concerned citizens today were brought here intentionally by scientists and range managers in the past. At one point these plants were viewed as the salvation of Arizona’s grasslands; now they are perceived to be one of the biggest threats to the continuation of its native ecosystems. Each year millions of dollars are spent to eradicate species that only decades ago cost millions of dollars to introduce.

Lehmann lovegrass has tied itself to humanity, using roads cut across the landscape to radiate outward. This species has even formed a strange symbiosis with border militarization. Everywhere that the border wall and its accompanying roads are built, lovegrass moves in, blown by the wind, hitched to cattle, or stowed away on the tires of construction vehicles. They have become intertwined, the wall and the invasive species, chasing one another across the scarified borderline.

Saguaro

Relocated saguaros (Carnegiea gigantea) held upright by tow straps and loops of carpeting

Heading west along the southern flank of Atascosa Peak, green and white Border Patrol vehicles speed by in clouds of dust, the cages in their truck beds rattling. They drop down into the broad expanse of a rolling plain known as Bear Valley and zoom past a side road leading to one of the biological crown jewels of the arid west: a drainage called Sycamore Canyon.

In 1946, renowned botanist Leslie Goodding described Sycamore Canyon as “a hidden botanical garden.” Draining the waters of the Highlands south into Mexico, Sycamore Canyon is a prime demonstration of the ways in which ecological continuity defies rigid political boundaries. In this place, stout alpine wildflowers mingle with decadent shrubs from the sultry tropics in the dappled light of the canyon bottom. Birdsong echoes between imposing rhyolitic spires. Painted redstarts (Myioborus pictus) flit over pools lined with ferns and columbine (Aquilegia chrysantha), while overhead turkey vultures (Cathartes aura) wheel lazily above ocotillo (Fouquieria splendens) and juniper (Juniperus arizonica).

The entrance to the canyon is marked by a massive oak (Quercus emoryi) and walnut (Juglans major), their bases fused together, embraced in a complex relationship of shared mycorrhizal networks and antagonistic allelopathy: even as they share resources below the soil, the roots of these trees exude chemicals that keep the growth of other species around them in check. They can at once provide mutual aid and staunchly defend their territory—plants, like humans, have a complex nature. Beyond this point the canyon walls close in and create microclimates that bring disparate biogeographic regions into contact with one another in a startling display of ecological diversity.

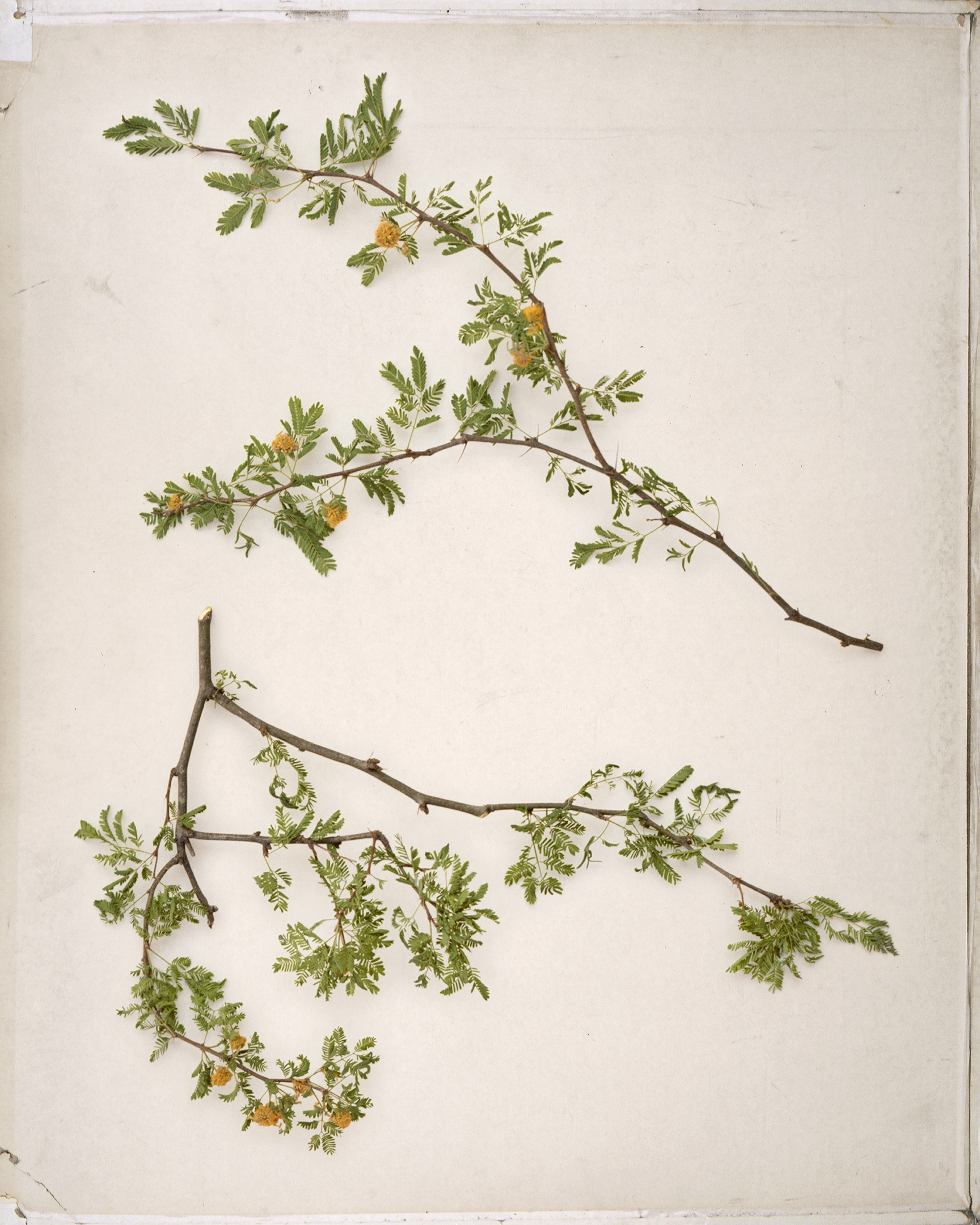

On a shaded canyon edge, a honey-like fragrance divulges the presence of sweet acacia (Vachellia farnesiana). This species is rare in southern Arizona, known to inhabit only a handful of localities, and it has not been reported in this canyon since 1937. Beyond the acacia, as the elevation steadily drops, a glance up through the canopy of sycamore (Platanus wrightii) reveals saguaros (Carnegiea gigantea) on the hillsides—a strange juxtaposition.

Sycamore Canyon, an oasis of biodiversity

Santa Rita prickly pear (Opuntia santa-rita)

Mariposa lily (Calochortus ambiguus)

Of all the species found in southern Arizona, there’s none more iconic than the saguaro. These are the largest cacti in the United States, reaching heights of forty feet, which makes them the tallest trees in many parts of the Sonoran Desert. They have a force of personality that links whole food webs around them: their flowers, fruit, and seeds serve as essential sources of moisture and nutrients, which are generously offered even in the driest years. Studded in clusters of thorns, the intimidating exterior of these plants belies their role as a refuge from the harsh conditions of the desert. Birds, mammals, reptiles, and insects will all shelter in holes dug into the flesh of these cacti, taking advantage of the thick, water-filled epidermis of the plant to keep them cool during scorching summer days. In the Atascosa Highlands, saguaros are found on exposed slopes where the mountains integrate into parched desert plains, forming an important biological link between desert and highland ecosystems. For the last ten thousand years, saguaros have been moving in an opposite pattern from silverleaf oak. As the climate has gradually warmed, their range has been expanding northward and into higher elevations—movements that have been closely observed by the Tohono O’odham people over the course of millennia.

“In our way of thinking, the Saguaro is a person,” said Tohono O’odham Elder Joe Giff, when asked about the plant. “That’s where Saguaros came from; in the stories it was somebody who turned into a Saguaro.” To the O’odham, who have called this region home for thousands of years, the saguaro is a plant which unites spiritual and physical sustenance and serves as a partner to desert people, even originating as one of them. Their understanding of this plant as both resource and kin has fostered a strong conservation ethic. An observer of the O’odham tribe in the early twentieth century noted: “When clearing away brush for the construction of roads [the O’odham] frequently curve the road for the sole purpose of saving one or more Saguaros.”

This has not been the intention of the border wall. At the bottom of Sycamore Canyon, the border is marked by strands of barbed wire crossing the stream bed. A wall hasn’t been built through the canyon yet, but not for lack of trying. Above the dry creek bed looms Table Mountain, made up of two peaks connected by a low saddle: the north peak is in the US, and the south summit in Mexico. Where there should be a hillside covered with stately saguaros, there is just a trail of rubble and loose gravel snaking down the mountain side.

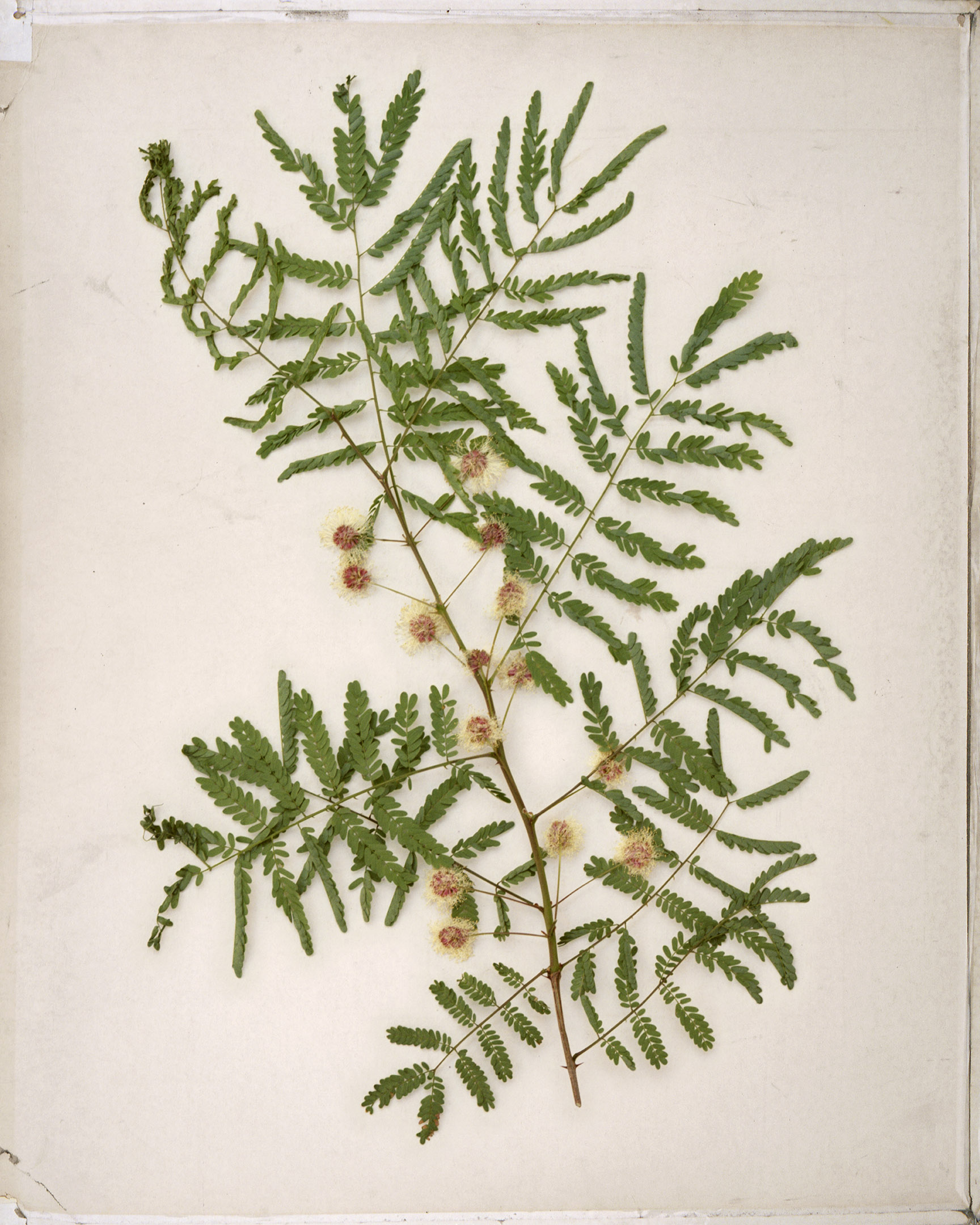

Sweet acacia (Vachellia farnesiana)

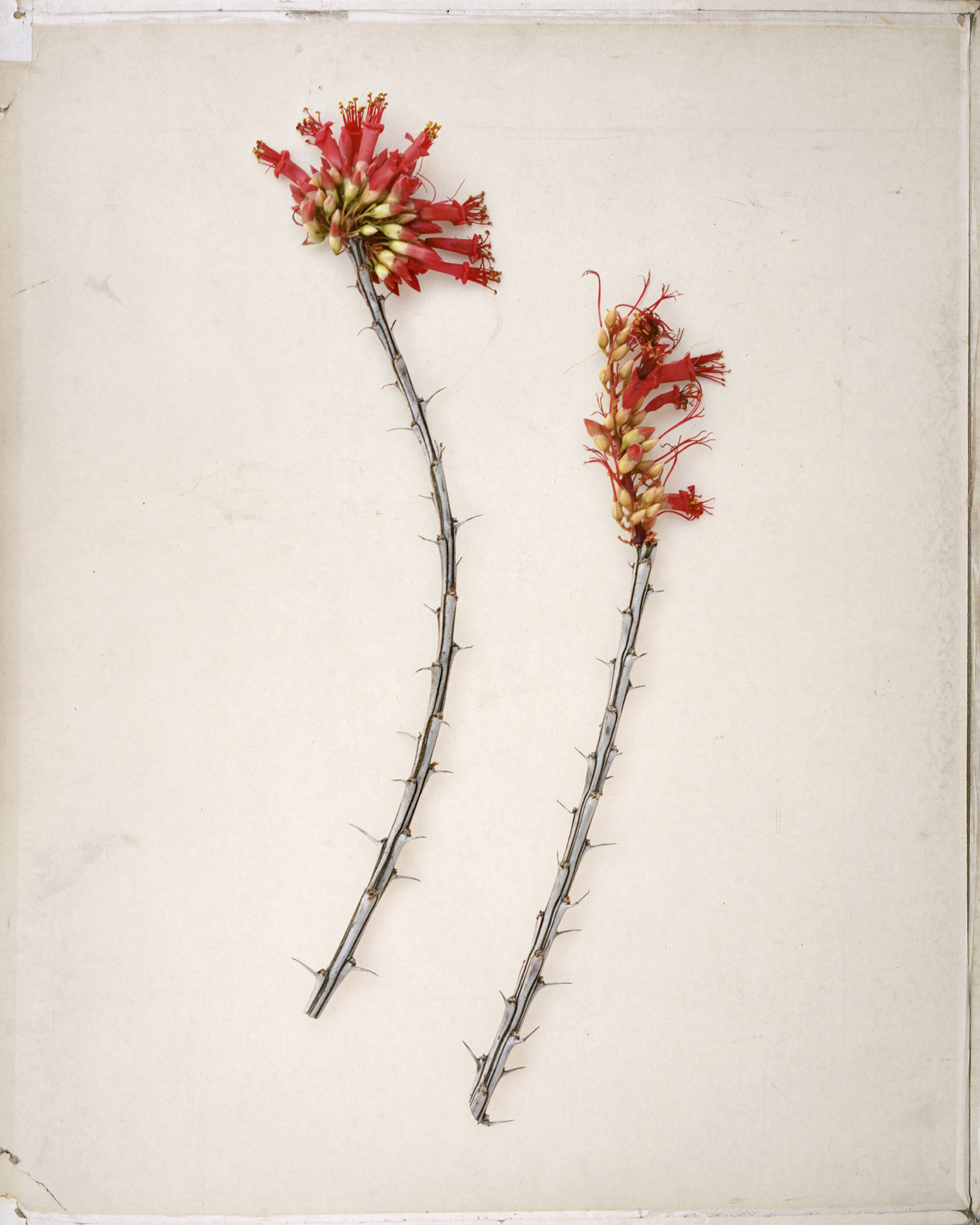

Ocotillo (Fouquieria splendens)

Gatuña (Mimosa grahamii)

False indigo-bush (Amorpha fruticosa)

Sierra Madre lobelia (Lobelia laxiflora)

Netleaf oak (Quercus rugosa)

Bulldozers have scored the ground with tread marks where they came down the blasted slope and into the canyon, and there are large chunks dug out of the canyon walls. Whole swathes of the area have been completely bladed and cleared. A few saguaros were pulled off Table Mountain and haphazardly replanted on a chewed-up mesa top nearby. Their roots were severed in the process of removal, and they’re being held up by ratchet straps, an artifact of heavy industry and a reminder that the construction crews could be back at any time.

This willingness to balance people’s desires with respect for nature has allowed the O’odham to live in and around the Atascosa Highlands for uncounted generations without leaving massive scars on the landscape. Their concern for the natural world demonstrates an understanding of their place within it. In marked contrast to the O’odham, the US government waived forty-one state and federal environmental laws so that the border wall could be imposed on the land with no oversight, no review, and no environmental surveys of the habitats it demolishes.

These ancient cacti at the border, their arms raised to the sky in supplication, have witnessed the concept of a border taking shape, and many have fallen victim to this culture which will build a straight road at any cost, even in this remote canyon where the geology, topography, and ecology all seem to invalidate the notion of a solid boundary.

The most recent period of active construction has ended, but a shift in the political winds offers only a temporary reprieve. Lack of rain makes desert ecosystems slow to recover from disturbance; as the drought continues, attention and concern over the effects of wall construction have evaporated like water in the gathering heat of an Arizona summer. The rippling effects wrought by this latest round of border wall construction will be evident for centuries to come in the ecological and social fabric of the borderlands.

For now, the silverleaf oaks have a moment to shake the dust from their leaves. Sweet acacia can bloom again next year in Sycamore Canyon. The saguaros continue to stand witness.

And the border wall stands, unfinished—an uncertain presence that has come to rest and make its home in this ancient land.

Unfinished border wall construction at Cerro del Fresnal

Atascosa Borderlands is a visual storytelling project combining botanical survey, oral history, and documentary photography to explore a notoriously rugged landscape straddling the US-Mexico border.