Wild Fire, Flat Water

-

Fire

Blue smoke twists and rises. The fire snaps and hisses and crawls low across the ground, roaring and huffing when it catches in a short-lived breeze. Blades of little bluestem bend and shrivel, curling into tiny black fists. Flames press themselves against the trunks of the few cedar trees that hover like ghosts in the smoky daylight, scattered among the grasses of the prairie. With a sound like the inhale of some great beast, one of the cedars catches. Fire snatches the crown. The tree, moments ago a silent, dark mass in a land of smoke, becomes a wild dance of flame.

Prairie Ours is the language of wind sifting through grass. We are sister to fire, brother to bison. We move with the rising sun; turn with the earth. We are the old myth that runs in your blood. We are one. Little bluestem, rough gayfeather, Missouri goldenrod. Meadowlark, upland sandpiper, springtail. Leadplant, prairie rose, sharp-tailed grouse. We are one. Listen.

For thousands of years, the land now known as Nebraska was prairie land: tallgrass prairie in the east, mixed grass prairie in the Central Loess Hills and Sandhills, shortgrass prairie in the Panhandle.

Few landscapes thrive by catching on fire, but prairies rely on such dramatic disturbance. The roots and buds of perennial grasses, wildflowers, and sedges reach deeply into the soil, protected from flame as the fire recycles nutrients, creates space for new growth, and eliminates shade in its hungry consumption of trees.

When the modern Great Plains came into being twelve thousand years ago with the close of the Great Ice Age and the retreat of the glaciers, the great prairies moved north.

When storms descended on the plains, lightning might set the land ablaze; wildfires would burn hot in an ocean of grass. For thousands of years, Plains Indians understood that fires on the land promoted the growth of grasses that drew in the bison.

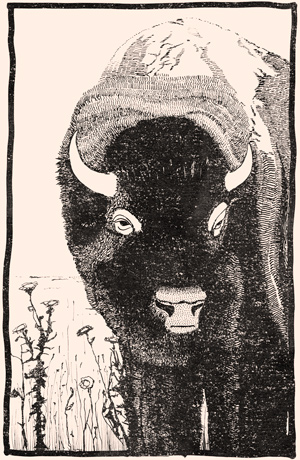

Prairies depend, too, upon the disturbance patterns of grazing. Bison, elk, and deer ate their way across great distances of grassland, eating some areas down, leaving others untouched. In their wake grew a diversity of plant communities and wildlife habitat.

Once, the bison roamed as the seasons waxed and waned, as generations of people came up on the land like their ancestors before them, as fires burned, as the grasslands did their patient work. The waters of the Platte River that carried sand and gravel down from the mountains in the west carved its meandering path into the loess hills. Its waters ran, shallow and flat.

Once, humans and prairies participated in a shared ecosystem.

There was music and story in the wilderness. There was fire in heart and land alike.

Today, what little prairie remains is altered, damaged, and overlooked.

We no longer see variations in stem color or soil texture, or note when the cool-season grasses grow, when the wildflowers bloom.

Our lives have grown too loud to hear what the land has to say.

We have come to fear fire.

We no longer see.

-

“Oh, I think that’s what’s wrong with humans: they’ve lost their sense of place. . . . That’s how you get tied to the earth, and the land, and the plants, and the animals—is having a sense of place. What I’ve noticed over my career [is that] all good land managers—the ones that really care, that make an effort, that really do a good job—are the ones that love the place they’re managing. “Another thing is seeing. You need to be able to see the changes, and boy, I just don’t think a lot of people have that capability. When your prairie’s going downhill, you’ve got to be able to see the plants, and how they're responding, how the wildlife’s responding; and I just don’t think people have that. Some people don’t have that capability to see. Some do, and they’re the good ecologists. Those that care and those that can see. Bill Whitney is one of the best seers I’ve ever known.”

Aurora, Nebraska—The Loess Plains

Bill Whitney’s red pickup is littered with an untended clutter of practical objects—measuring tape, dried prairie seeds, an overturned thermos, scraps of paper—suggesting a driver whose mind is outdoors even when his body is not. A slender man with a long, slouching frame, a frayed baseball cap, and well-worn boots, Bill is an Aurora native, a prairie ecologist, and a bit of a mystic. “I’m probably considered a dreamer. ‘Probably’ is probably not the word to use—I am considered a dreamer, by people who’ve known me a long time. They probably think I don’t get anything done.”

After college, Bill and his wife, Jan, returned to the loess plains of Hamilton County in central Nebraska to build their lives together. “To me, it was all about coming back home, discovering the prairie,” says Bill. Once a sea of mixed-grass prairie, roughly 90 percent of land in Hamilton County is now in crop production.

-

Bill and Jan founded the Prairie Plains Resource Institute in 1980. With its “hands-on, see-the-landscape, be-in-the-landscape approach to restoration,” PPRI has worked to preserve remnant prairie and has converted over twelve thousand acres of cropland to local ecotype prairie species, managed with cycles of prescribed fire and grazing.

“Patch burn, graze,” says Bill.

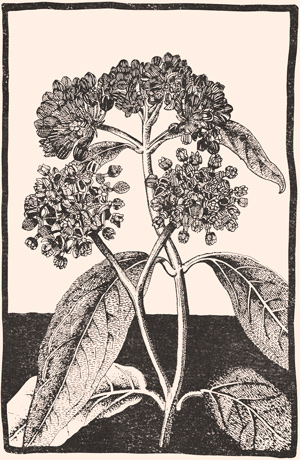

Every year, the PPRI staff collects thousands of pounds of wild prairie seeds, which are stored and dried on the floor of the barn at Gjerloff Prairie: Sullivant’s milkweed, white heath aster, false boneset, and compass plant lie piled in beautiful, intricate heaps atop blue tarps. Eventually, they will be planted on PPRI preserves, on conservation land, or in the fields of private landowners.

Bill speaks an ecologist’s language with a rural, midwestern lilt. He’s a steward of the native prairie in a land of corn, soy, and cattle, though he doesn’t see himself as an outlier. Restoring the land, he believes, means being part of your community. “You don’t come out and lead with a philosophy of restoration. You gotta talk cattle. You gotta talk grazing rates, numbers. That other stuff comes through friendship development. . . . You still have to be pragmatic. We’re still agrarian. [PPRI] fits into our place as small-town, rural people. None of that’s changed.”

-

-

Bill is driving a four-wheeler along the mowed paths of Gjerloff, through the native mixed-grass prairie and the restored tallgrass prairie, alongside bluffs and valleys, up to the vista overlooking the Platte River, noting along the way where the fire and cattle have recently been. He frequently stops and gets out to narrate the histories of various plants—why they matter, why they’re beautiful—as if praising old friends too modest and quiet to tell their stories themselves. He drops to his knees and brings his nose nearly to the ground to peer at the delicate green-gray leaves of leadplant; he gently rotates the wide head of a compass plant; he admires the curving tendrils of deer vetch.

“The philosophy behind doing this work is to be a part of that process, to have what I call more of an ideal about restoring our viewpoint, our knowledge base, enlarging our cultural vocabulary about place—and the beauty. So there’s a human restoration component by trying to restore something we didn’t create in the beginning. By saying something kind of mystical like that, I’m not attributing any spirituality to the virgin prairie. To me that’s a physical thing, that’s how the system developed; it’s systems ecology.”

-

“The philosophy behind doing this work is to be a part of that process.”

-

In Hamilton County, systems ecology has been largely displaced by industrial agriculture. Corn and cattle are king; acres are valued in dollars, not species diversity; fire is feared and water is controlled through irrigation and diverted rivers. Of Nebraska’s 49 million acres, 9.5 million grow corn; 5.7 million acres grow soybeans; 23 million acres are rangeland for cattle.

The four-wheeler dips and heaves. Big bluestem grows chest-high and golden, leaning heavily into the path, thudding against the roll bars and the hood. It’s late September, but the cool morning is giving way to a hot afternoon, thick with butterflies.

“There are signs of discernment. And that just means wisdom, you know. It’s ancient wisdom that’s in nature, because it’s the pathway to the unknowable. We have to have a place for our imaginations and our bodies to roam wild,” says Bill. “Is this wilderness or not? Wilderness is a figment of your mind. It’s not the wilderness of three hundred years ago. But we have to think that our view of wilderness, and wilderness itself, is still possible.”

“We have to have a place for our imaginations and our bodies to roam wild.”It takes a moment for novice eyes to adjust to the prairie. A blur of waving grass conceals an unfolding universe. To see the prairie is to see up close. Its beauty lives in subtle detail. Here is an ancient ecosystem, a deep and wild intelligence. There are no individuals on the prairie, no understanding only one species, no clear delineation of one acre, no asking one question.

“Somewhere in college when I started to become a biologist, I had a—for lack of a better word—a vision. It was a picture of myself out in a landscape with water and wildness. I didn’t know where. It wasn’t as refined as the prairie. I didn’t know anything about prairie. And I considered my interests to be not either in aquatic biology or terrestrial biology, but a combination of the two in the sense of a watershed. So I had a mental picture of working on the landscape—not on a small system.” Bill has collected and planted native seeds in Aurora for four decades. For him, wilderness encompasses the physical landscape as well as the cultural one. The wild and the human are severed only when the land is imagined as a passive and malleable tool for human progress and, therefore, never truly seen.

Bill sees a particular wisdom in the prairie. “This is important groundwork to know how to restore something we might essentially depend on at some point; because if we don’t have the knowledge, culturally, to work with ecosystems—including agricultural ecosystems—in a sustainable manner, we’ll just run them down very quickly. . . . We’re running down our fisheries, forests, and grasslands because of the survival economics involved, and the only thing that you have your recourse to at some point is your knowledge and the fact that the sun has got the energy to put back into the system. . . . It’s all about carbon in the soils. It’s all about regenerative process. Being human, we also still need beauty and community, which means we need stories and art and music.” For Bill, healthy and diverse ecosystems are not limited to untouched or unused land. Human culture can—and should—play a vital role in the surrounding landscape, just as the land should play a vital role in a thriving human community. Wilderness can include a human presence as long as we allow the land to guide our use of it and expand our cultural knowledge to include an awareness of the ancient wisdom that resides in the grasslands and the waterways.

“We’ve had tremendous success adhering to this model of restoration. [It’s a] testament to the fact that we can create physical change that reflects a different way of looking at things. That’s art, right? That’s really all it is.”

The loess hills roll softly down to the eroded plains at the edge of the Platte River. Sandbars intersperse the water, which is wide and blue, flowing, but hardly appearing to move, meandering until it disappears into the trees beyond. Bill looks out over the river. “This does the heart good every time that you can stand out here.”

-

Grass

Little bluestem

Switchgrass

Blue grama

Prairie cordgrass

Porcupine grass

Virginia wild rye -

-

Flat Water

Nebraska—Nebrathka—is an Oto word meaning “flat water,” named for the Platte River that runs west to east across the center of the state, 310 miles until it flows into the Missouri River.

As the glaciers advanced and receded in the Rocky Mountains during the Ice Age, they ground up the land, leaving behind sands and gravels that were carried eastward by wind or swept into newly flowing streams. The Platte carved itself into these sediments.

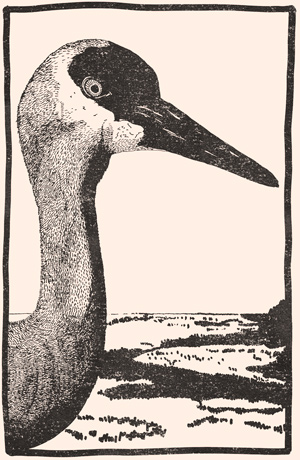

Every year, for thousands and potentially millions of years, sandhill cranes have crossed Nebraska during their spring migration. With the formation of the Platte River twelve thousand years ago, the cranes began converging on its sandy banks to rest and refuel before continuing northward to nesting grounds in Alaska, Canada, and Siberia.

“At the beginning all things were in the mind of Wakonda . . . the First Spirit. All creatures including man were spirits. They moved about in space between the earth and the stars. They were seeking a place where they could come into a bodily existence. They went up to the sun, but the sun was not a good place to live. They moved on to the moon and found that it was not good as a home. Then they descended to the earth; it was covered with water.”

-

Nebraska was covered with water. Sixty-six million years ago, the Cretaceous Western Interior Seaway began to recede, marking the end of hundreds of millions of years of intermittent ocean on top of Nebraska. As the seas rose and fell, thick layers of bedrock were deposited, laying the foundation of the Great Plains.

Walk anywhere in Nebraska and you are walking above the fossilized remains of ancient mollusks and clams, of the fifty-foot-long plesiosaur with its long, sleek neck and four paddles, of the three-hundred-million-year-old, shell-crushing Campodus variabilis, a shark whose teeth curled backward below its jaw in tight, jagged spirals.

As the inland sea retreated from the center of the continent, the Rockies rose in the west. Eastbound streams carried eroded sediment from the mountains—clays, sands, gravels, and silts—and deposited them across the Great Plains into what became the Ogallala Group in Nebraska’s geologic record.

The Ogallala Aquifer is a vast supply of groundwater, saturated throughout permeable sediment. The aquifer lies beneath eight states in the High Plains; two-thirds of its water lies beneath Nebraska. The aquifer feeds the Platte and many other rivers, streams, and wetlands. It accounts for 95 percent of Nebraska’s irrigation water.

The aquifer lies beneath eight states in the High Plains; two-thirds of its water lies beneath Nebraska.With the invention of the center pivot irrigation system in the 1960s, farmers and ranchers gained a greater capability to utilize the aquifer. When commodity prices rose, millions of acres of native prairie across Nebraska were plowed to plant row crops, rendered viable with a guaranteed water source.

A center pivot can pump 900 gallons of water per hour and makes one lap around a 160-acre quarter section of land every 48 hours. There are roughly 55,000 center pivot irrigation systems in use on 6.7 million acres of land in Nebraska.

In many places, the water levels of the aquifer are declining, unable to naturally replenish what is being pumped out. Much of the groundwater is now contaminated with nitrates from fertilizer and may no longer be safe to drink untreated. Denied groundwater inflows, many rivers and creeks grow thirsty.

-

-

Paul Olson and Wallace Wade Miller (Thio-um-Baska), The Book of the Omaha: Literature of the Omaha People (Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 1979).

-

Bassett, Nebraska—The Sandhills

Dan Frank’s not your typical rancher,” says Gerry Steinauer, state botanist for Nebraska Game and Parks. “He dresses like a hippie.” Dan is twenty-nine years old, with a scruff of beard and blond hair that reaches the middle of his back when it’s visible, though it’s more often folded into a baseball cap that has an off-center Smokey the Bear patch glued to it. He’s a fourth-generation Sandhills cattle rancher and a first generation conservationist, learning to be both at once.

Dan and his girlfriend, Alison, live just outside of Bassett on a five-thousand-acre cattle ranch, where pale green and golden grass covers shallow hills, where cedar trees are clustered in valleys, and Black Angus cows stare and bellow from the fields.

The Sandhills region covers more than twenty thousand square miles of north-central Nebraska. Once bare and blowing sand, the semi-arid region is now covered with sparse, native mixed-grass prairie. Neither its sandy soil nor steep hills make for good crop production, and so, since white settlement in the late-1800s, the Sandhills have primarily been used as grazing land for cattle, by and large sparing the prairie from the plow.

-

-

Dan’s ancestors immigrated from Germany to Valentine, Nebraska, near the turn of the century. His great-grandfather later moved to Bassett and purchased the land that he ranched, followed by Dan’s grandfather, and then his father, and now Dan.

Dan appears slightly bewildered by his decision to willingly step into a family inheritance of hard labor, year-round management of thousands of acres, and tending to hundreds of cattle.

“Well, the only reason you’re here is to take care of the land,” says Alison. “You guys all have such strong visions.”

“The only reason you’re here is to take care of the land.”Dan’s father’s vision for the land was one of steady expansion and a healthy, growing population of cattle. Over the years that he managed the land, the ranch grew as he bought adjacent pastures. Ranch land does not come cheap, however, and the Franks accrued a great deal of debt. With the rise of commodity prices and the invention of the center-pivot irrigation system—which would provide enough Ogallala Aquifer water to grow crops in even the poor soil of the Sandhills—came an opportunity for the Franks to pay their debts. They plowed seventeen fields, planted row crops, and installed center pivots.

In 2010, Dan graduated from the University of Nebraska with a degree in diversified agricultural studies and grasslands ecology. He and Alison moved to Bassett shortly after and settled into the family home, where Alison’s gallery of nature paintings collected from yard sales now hangs in the living room, a prairie calendar garden sprawls out front, and a young and tidy orchard grows out back.

-

“Humans have the list of what comes first and what doesn’t, and humans are at the top of the list every time.”

-

Dan returned home to implement his own vision for the land he loves: that of a rancher and restoration ecologist. “Humans have the list of what comes first and what doesn’t, and humans are at the top of the list every time. We should definitely care about our fellow man. But does it mean we should do it at the sacrifice of all of our environment?”

His first step was to plant the crop fields back to grass. In 2016, Dan and Alison planted 670 acres of grasses and wildflowers—a mix of twenty-eight native prairie species—with funding from the Natural Resources Conservation Service. “Farming can be pretty lucrative at times. Right now it’s not, so actually it’s a pretty good time to plant it back to something; because we’re still going to make money on this, still going to graze it, produce a crop. It’ll just be a beef crop rather than a grain crop. Prairies evolved with grazing. They need to be grazed.”

-

Dan and Alison are standing in the middle of a newly planted field, admiring the successful growth of the prairie plants and calling out the names of species they now know and recognize. Alison pulls a bag out of her pocket and begins collecting seeds. Dan marvels at how tall the grasses have grown, that the sunflowers tower over his head. When the wildflowers and grasses are well established, Dan and Alison will begin a rotation of prescribed fire. Dan’s fifty cattle will graze the pastures.

For the first season of the new planting, Dan used the center pivots to water the fields. Ultimately, he plans to put the pivots into retirement. His vision is one in which his land practices are aligned with a thriving grassland ecosystem, where the roots of perennial grasses do not rely on aquifer water. Where the land, too, can claim its inheritance of fire and healthy grazing.

“We’re trying to not manipulate the environment to what we want, but trying to manipulate what we want for the environment we have.”Both Dan and the ranch are, on the surface, manifestations of a century of High Plains cattle ranching. But Dan has come to see where the land is struggling and where it is thriving. He sees the aquifer disappearing, its waters contaminated. He sees intelligence and beauty in the Sandhills ecosystem. He registers loss where invasive eastern red cedars, smooth brome, and Kentucky bluegrass have crowded out the native plants. He wants to make a living as a rancher, like his fathers before him. And he wants to heal the land. “The shorter amount of time you’re here, the more superficial it seems. But the longer you’re here—everything gets more complicated with time and you make more decisions and then you think, ‘Am I going to regret that decision?’ But hopefully for every step back, I’ve taken more than one step forward.”

Dan is a fourth generation rancher. But he is doing it differently. “We’re trying to not manipulate the environment to what we want, but trying to manipulate what we want for the environment we have.”

He and Alison are articulating and implementing a vision that aligns the needs of this five thousand acres with their own. “It’s for the maintenance and improvement of our land for future generations and for the future of the land itself—for the land itself without humans, or for humans to have the land. Rangeland is shrinking. And it’s only going to continue to shrink. At what point are we going to stop that shrink and maybe even get a little back? I hope we do. We’re doing it. We’re trying.”

-

Wildflower

Hairy golden aster

Partridge pea

Downy gentian

Compass plant

Whorled milkweed

Silky prairie clover -

-

Ice Age Mammal

Woolly mammoth

Giant camel

Mastodon

Ice Age bison

Saber-toothed cat

Musk ox

Giant sloth

-

Macy, Nebraska—The Omaha Reservation

Long ago, Earth and Sky were one. Wakonda created the elegant long-necked crane, the gray wolf whose cry shook the earth, the buzzard who flies without effort, man and woman. Corn and buffalo were gifts of sustenance. The Sacred Pole, hewn long ago from the tree in the forest that was lit like the sun—the tree that the Thunderbirds visited, leaving paths of fire in four sacred directions—symbolized the Omaha tribe. Named Umoⁿ’hoⁿ’ti, or “the Real Omaha,” the Sacred Pole was seen to be a person unto himself who guided the tribe and held them together.

By the early eighteenth century, the hunting and migratory territory of the Omaha ranged from the Cheyenne River in South Dakota to the Platte River in Nebraska. The Omaha lived in semi-permanent villages, residing in earthen lodges and moving to new lands every ten to fifteen years. They tended gardens of corn, beans, and squash. Every year came the buffalo hunt. The tribe traveled hundreds of miles to reach the herds. Every year, with great ceremony, Umoⁿ’hoⁿ’ti renewed the life of the tribe.

The land, its elements, and its creatures were kin to the Omaha. When new life came into the tribe, a ceremony was held that welcomed the child into the world and time of the Omaha. The Creation was asked to guide the child through the four stages of life:

“O you—sun, moon, and stars, All of you that move in the heavens, I bid you hear me, Into your midst has come a new life. Consent, I implore, make its path smooth That it may reach the brow of the first hill.”Generation after generation, the traditions, songs, and stories were passed down. The buffalo wandered the great prairies.

-

Native Americans across the continent were ravaged by smallpox after contact with the Europeans in the 1700s. In the Great Plains, the buffalo were all but exterminated by white settlers in the mid-1800s. For decades, tribes were massacred and forced from their sacred lands; survivors were resettled on to unfamiliar and undesirable territories with poor soil or forcibly moved to Indian Territory in present-day Oklahoma. Well into the 1900s, the government took the Native children to boarding schools and imprisoned adults for carrying out tribal ceremonies. Allotment policies forced tribal members to divide lands held in common into individual properties. Forced ever further into poverty and desperation, many Native Americans sold what little land they had to white farmers who offered to buy it for a fraction of what it was worth.

The goals of the federal government’s assimilation policies were brutally successful in breaking traditions and languages, in severing collective memory and relationship to sacred place. The spirit drained from the land and with it much of the fire in the hearts of the people.

-

-

When the way of life of the Omaha no longer could include the buffalo hunt, when the tribe’s ritual connection to the land and each other through ceremony was no longer possible, it was decided that Umoⁿ’hoⁿ’ti should be buried with the chiefs who had once been charged with his care. In 1888, the Omaha were instead persuaded to give the Sacred Pole to the Harvard Peabody Museum, where it remained for the next hundred years. With its removal from the life of the tribe, the traditional ways of the Omaha fractured ever further.

-

“How do you develop culture? How do you grab it and hold it?”

-

“I spent most of my life away from this place when I was a kid.”

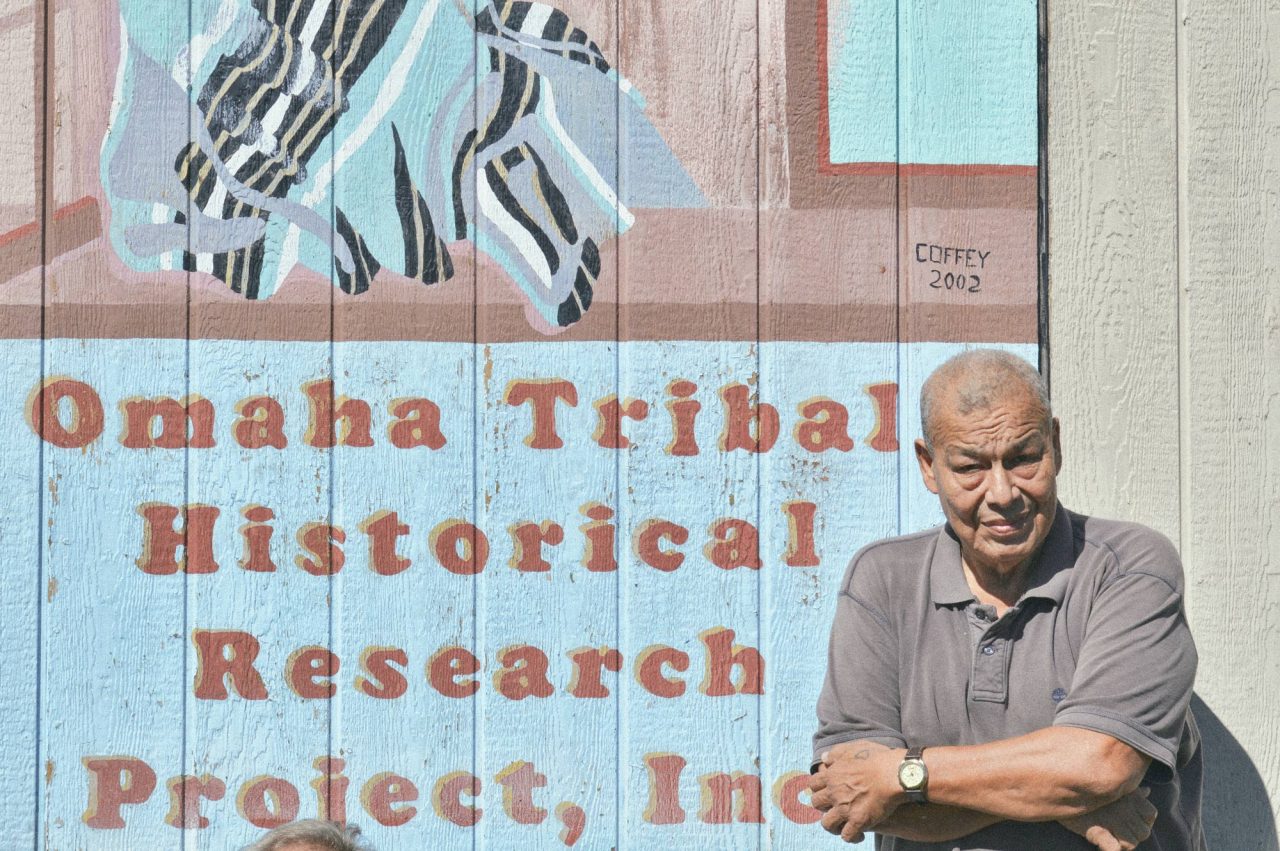

Dennis Hastings is sitting in his small house on the Omaha Reservation in Macy.

A few miles from his home, steep grassy hills lead down to the banks of the Missouri on the eastern edge of the tribal lands, where morning fog obscures the boundary between water and sky. By the mid-1800s, the Omaha had settled along the Missouri River in northeast Nebraska, leaders in the burgeoning fur trade. The power they accumulated as traders helped them to secure an early treaty with the United States government, ensuring lasting ownership of a small bit of their territory.

“When I did try to speak Omaha, everybody laughed at me.”Dennis’s home doubles as the office of OTHRP, the Omaha Tribal Historical Research Project, founded in 1974. Together with his two-person staff—Margery and Richard—Dennis undertakes a wide range of projects and advocacy: from working to repatriate sacred Omaha objects to producing Omaha language dictionaries and workbooks, from writing a history of the Omaha people to developing a new tribal constitution.

Dennis was born on the Omaha Reservation. “I was with my grandma and she took care of me. My mom was not around or my dad. My grandma spoke Omaha to me all the time. I picked up from her whatever she said. But when I did try to speak Omaha, everybody laughed at me because I spoke it in the way that women speak it.”

Dennis was taken from his grandmother’s home when he was six years old and sent to boarding school in North Dakota, where he remained for the next eight years.

”O ye winds, clouds, rains, mist, All of you that move in the air, I bid you hear me, Into your midst has come a new life. Consent, I implore, make its path smooth That it may reach the brow of the second hill.”

-

Dennis refers to his great-grandmother, New Moon Moving, as simply “grandmother.” She knew the old ways. One night, as a young child, Dennis was frightened by a strange noise outside the front door. He asked his grandmother what it was. “She went and opened the door and went outside. And then she came back inside and got her bundle and her tobacco, and she went out and burned four directions around the house. Then in the morning, we woke up, and the woman across the street had died. And [Grandma] said, ‘She came here last night.’ It’s things like that—that you were raised up with and you kind of understood—that nowhere in the outside world is there anybody or anything else who could understand that. But we understood it there. Grandma used to say that people’s spirits, they live all over here.”

Dennis could not speak of such things at boarding school. “Oh no, they did not allow you to speak [Omaha] at all. Matter of fact, you got punished real bad. . . . They brutally hit you. They put soap in your mouth, made you stand in the corner. . . . They treated me just like I was—like a prisoner, and I didn’t have no soul or I didn’t have no feeling.”They cut his long hair and did their best to erase the tribe from his memory.

”O ye winds, valleys, rivers, lakes, trees, grasses, All of you that belong to the earth, I bid you hear me. Into your midst has come a new life. Consent, I implore, make its path smooth That it may reach the brow of the third hill.” -

When physically running away from school didn’t work, Dennis turned to books. “When I was learning how to read, I realized that that was my way out.” Before he could read or speak English fluently, Dennis came across a copy of The Omaha Tribe at the library—a comprehensive history of the Omaha people written by Francis La Flesche, the son of an Omaha chief, and ethnographer Alice Fletcher. He checked it out again and again, hungry for this exposure to the history and customs of his people.

While at boarding school, Dennis’s grandmother died. He was not allowed to attend the funeral. “That was a very rude awakening for me. I started realizing that from now on in my life I have to be very serious about what I do. That’s how I became a radical in my own thinking. How do you develop culture? How do you grab it and hold it?”Dennis participated in the Indians of All Tribes’ occupation of Alcatraz in 1969 and the American Indian Movement’s occupation of Wounded Knee in 1973. At college in California, he chose to major in applied anthropology, focusing his studies on the history of the Omaha tribe. He made up his mind to return to the reservation in Macy upon graduation, intent on carrying out New Moon Moving’s wish for the traditions to be brought back to the people.

-

“Birds, great and small, that fly in the air;

Animals, great and small, that dwell in the forest;

Insects that creep among the grasses and

Burrow in the ground:

I bid you hear me.

Into your midst has come a new life.

Consent, I implore, make its path smooth

That it may reach the brow of the fourth hill.” -

Dennis struggles to articulate what it means to be Omaha. Much of what he has learned of the tribe’s past is no longer visible on the reservation today. It is hard to see what the future holds. He is caught between the tradition and memory of his ancestors, the trauma of boarding school, and the modern reality of a tribe that is only ever further removed from the time when the culture and language were fully intact.

As the elders pass away, the Omaha language loses more of its native speakers. The Tribal Council was recently disbanded on charges of corruption. The median age in Macy is twenty-two. Young people who choose to stay on the reservation know it will mean working to beat the high odds of unemployment and poverty.

For the Omaha—in a fate mirrored in indigenous communities around the world—a thriving culture that evolved over thousands of years was forcefully and brutally pushed to the brink of extinction, along with the buffalo, and the prairie.

And yet, the Omaha remain. Umoⁿ’hoⁿ’ti was returned to the tribe in 1989. There are Omaha language classes at the Nebraska Indian Community College. There is an annual powwow. Dennis, too, is doing his part to try and restore the culture of his people—the language, the customs, the memory, the hope.

Like the prairie, you cannot simply put back what once was there. Cultural restoration is often relegated to isolated and struggling corners of communities that are plagued with poverty and addiction. It is easy perhaps for non-Native communities to speak of the importance of the Native voice, and yet, Native people and lands remain, by and large, abandoned to their fate by the outside world.

Dennis still feels the presence of his ancestors on the land. He knows his grandmother is with him. “[In] this house, when we first moved in, I woke up and that one door was open. I went over there, and I locked it and closed it. Then I looked up, and there the cupboards were all open! Then I remembered my aunt saying, ‘That’s probably your grandma. So just feed her.’ So I made a little plate of food and put it there and went back to bed.”

Many years ago, on a night when Dennis received word that the Omaha had won a hard-fought court case that would guarantee the repatriation of Omaha remains, he went to bed, exhausted. “About three or four that morning, I heard some people outside making noises. I got up and looked outside, and there was nothing out there. So I just went to bed again. All of a sudden, it’s almost, it’s like light—a burst of light—came back into my room. And I was looking at it. And I don’t know if I was asleep or I don’t know where I was, but I noticed that they were talking Omaha. And they said a prayer there, and then they went.”

Dennis was not allowed to grow up with the Omaha language, teachings, or ceremonies. While being Omaha is not something he has the words to define, it is something he knows how to be, something that is in his blood. He will continue his work. He will continue to leave plates of food out for New Moon Moving, knowing that she is nearby and in need of nourishment.

-

“All of you in the heavens, all of you in the waters,

All of you in the earth,

I bid you—all of you—to hear me.

Into your midst has come a new life.

Consent, consent,

All of you consent, l implore.

Make its path smooth

That it may travel beyond the fourth hill.” -

“They floated through the air—to the North, to the East, to the South, and to the West and found no dry land. They were full of sorrow. Suddenly, from the middle of the waters, up rose a great rock. It burst into flames and the waters floated into the air in clouds. Dry land appeared: the grasses and the trees grew. The hosts of spirits descended and became flesh and blood; they fed on the seeds of the grasses and the fruits of the trees. The land vibrated with their expressions of joy and gratitude to Wakonda, the maker of all things.”

-

Paul Olson and Wallace Wade Miller (Thio-um-Baska), The Book of the Omaha: Literature of the Omaha People (Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 1979).

-

Wagner, South Dakota—Wagner Farm

The rain that has been grumbling and sputtering from low dark clouds since morning, having successfully kept everyone inside all day, comes down only after the last light is seeping from the sky. The first drops, fat and heavy, hit the sidewalk at dusk. Soon, there’s a full downpour on. All five cats have been ushered into the grand Wagner house. Built in 1919, its tall brick walls and white porch are visible now only in flashes of lightning and the dim glow around the rain-obscured porch light.

Gerry Steinauer and Grace Kostel are reading in the living room, occasionally commenting on the weather. South Dakotans dry-farm, without irrigation. They depend on wet spells and dry spells, warm days and cool days, all of which can come at the right or wrong time. The weather is important conversation. This rain comes too late in the season; the crops need to be dry for harvesting.

Of the several dozen photographs in the room, Gerry is seated beneath the three most prominent: two sepia-tinted portraits of Anna and Ferdinand Wagner, housed in ornate, golden frames, and, below them, an aerial photograph of Wagner Farm taken in the 1970s.

The 160-acre quarter section on which the Wagner house sits was deeded to Anna Wagner in 1862 as part of the Homestead Act, which granted families ownership of deeded land if they stayed for five years.

-

-

“Not only is the topsoil gone, that’s something that we can’t replace in our lifetimes. . . . That’s a thousand-year endeavor.”

-

Over time, Anna and Ferdinand acquired the neighboring 160-acre quarter section, as well as an additional 80 acres. Their son, Henry, bought the land from them and later invited his niece, Lucille, and her daughters, Grace and Martha, to live at the Wagner house after Lucille’s husband was killed in a farming accident. Grace grew up riding her horse bareback through the fields and pastures, leaping off to catch snakes and voles, patiently learning the names of the plants that her great uncle Henry taught her.

In 2007, Grace bought the farm from Lucille, who, well into her eighties, continues to tend the land. Gerry and Grace, both botanists, married in 2010. They live in Aurora but frequently drive three hours to the farm, where they are implementing a strategy and practice of land restoration. Of the farm’s 400 acres, 100 are unplowed prairie that has been overgrazed and overrun with smooth brome and Kentucky bluegrass. Gerry and Grace have set to work healing this remnant ecosystem using fire, grazing, and selectively applied herbicide. Of the remaining 300 acres of plowed land, they’ve planted 165 acres back to native grass through the Conservation Reserve Program—a government program that pays landowners to take cropland out of production and plant it back to grass to prevent soil erosion and provide wildlife habitat. Grace is clear that, though native plants exist again on this ground, this is not prairie—it is not yet an ecosystem. “Not only is the topsoil gone, that’s something that we can’t replace in our lifetimes. It will take generations of other people hopefully allowing that grass that we put there to recreate topsoil. That’s a thousand-year endeavor.”

-

-

Gerry looks out at the rain. “I think so much of the Midwest we don’t need to farm. It’s going to ethanol; growing bad corn to put fat on cattle. I think you could develop a new economic picture where it was used for grazing, and in the long term it’d be better for the land. We’re chewing up our soils, polluting our groundwater, polluting the atmosphere, polluting our rivers, by farming all this. But I don’t know if you’ll ever get mankind to do that.”

Indeed, talk of Gerry and Grace’s land management practices largely falls on deaf ears. While there is a widespread understanding of the value of corn and soy, there is little value afforded the many plants and animals that once blanketed the Great Plains. “People always want you to justify it from an economic perspective, but I always look at it as, well, they’re a living species,” says Gerry. “Why are humans any more important than a plant or a butterfly? . . . They’re living. They’ve been here millions of years, they’re part of the earth. They serve a lot of ecological roles that do help humans—if humans could try and understand that—as pollinators, or keeping the soil healthy. I think we have an ethical responsibility for keeping these species on earth.”

Taking advantage of a break in the rain the next morning, Gerry and Grace are out on the land, wandering between the front lawn of the Wagner house and the horses in the pasture, pausing to bend down and see how the prairie plants are doing. “I’d rather be here than most places, just walking around the prairies,” says Gerry. He draws Grace’s attention to a pitcher sage plant. “We’ve probably got fifty species of native plants in this prairie, but a lot of things are gone that should’ve been here. We’re putting a few plants back: we reseeded compass plant, sky blue aster, a lot of prairie violets, which are neat. We have about six plants of plains milkweed, which is a pretty uncommon plant in South Dakota anymore.”

-

“My personal relationship with the land, having been raised here, is that someday I would restore it as closely as possible to what it was before.”

-

Grace’s vision for the land is closely tied to her family’s history and the history of the land itself. She knows Wagner Farm did not come for free—a people, a culture, an entire ecosystem were the price of the Homesteading Act. The land given to white settlers in South Dakota had been promised to the Sioux. When she looks out on the land, she sees both the damage and destruction, and the place she knows and loves as home.

“My personal relationship with the land, having been raised here, is that someday I would restore it as closely as possible to what it was before. My great-grandparents arrived here and started farming it, and that’s been a tumultuous journey, because it’s not as easy to put things back to what they were as one would think. . . . The restoration process is familiar with my lifelong relationship to the land, because it’s a difficult one. It’s just not one of pure love. I was raised as a farmer person by farmers, and you learn to dominate nature in order to be successful. And in a way, that’s what we’re doing as restorationists—we have to dominate certain parts of what the land is in order to do what we think is best, because we don’t know for sure.”

Gerry and Grace do not know what will become of this four-hundred-acre piece of land. Its fate will extend beyond their lifetimes, as will the fate of Gjerloff Prairie in Aurora, and that of the Frank Ranch in Bassett. The continued care of these places will require that others choose to care.

According to Gerry, you have to look beyond people to have a sense of place. You have to get out in nature, extending your view of the world beyond human society. “I think people have to learn to live with the ecosystem that’s out there instead of trying to manipulate everything to their means,” says Gerry. “Most societies—they aren’t seeing what’s happening to nature, they don’t see the diversity in nature—they don’t see. They don’t understand nature. It’s hard for them to try and preserve it, because they have no concept of what it really is.”

-

Sedge

Short-beak sedge

Heavy sedge

Sun sedge

Needleleaf sedge

-

Fire “What has been just thrilling beyond belief is to set the prairie afire again and then watch what shows up. I had no idea of the ability of prairie plants to persist. All of these years that this prairie that’s native here at the farm has been grazed and hayed beyond recognizable prairie, those plants must have been there in some way, shape, and form, just under the non-native grasses, photosynthesizing—maybe a leaf here and a leaf there. And after we burned, they just exploded. And so my mother, who was also raised on this farm, can remember some of the colors, some of the plants that she picked as a kid. After that first burn, we were walking around out there. She’d say, ‘I haven’t seen this for sixty years.’ So that’s been really thrilling. That’s what keeps the hope alive.”

Flat Water

Nebraska—Nebrathka—is an Oto word meaning “flat water,” named for the Platte River.

The Platte flows west to east across the state, a river of rain and melted snow. Its tributaries are fed by the Ogallala Aquifer, filled by centuries upon centuries of rainwater that saturated sediment which was deposited millions of years ago by streams that carried away echoes of the mountains rising in the west. The aquifer lies on bedrock formed by an ancient inland sea. When the prairies arrived in Nebraska, the water rested below and the fires burned above.

The prairie is mostly gone. Irrigation drains the aquifer. The rivers grow thirsty.

The human perception that the earth is infinitely ours to consume led to the plow’s destruction of twelve thousand years of topsoil. This perception has far-reaching consequences for people and planet alike; the question is no longer if those consequences will be felt by human and non-human alike, but how. It is perhaps the most critical and the most successfully ignored question of our time.

Here is a different sort of question: What if the prairie is—fundamentally, critically, irrevocably—who we truly are? Or the forests? Or the rivers? What if the origins of our very bones cannot be distinguished from the origins of the loess hills and the prairie rose and the deer vetch?

No technology will recreate the prairie topsoil. No ethnologist will convey through words in a book what it means to be Omaha. We are here because of the work of eons—spans of time beyond what we can imagine. We are made up of the ancient processes of the earth. We are the inland sea. We are wild fire and flat water.

In nature, true endings arise only with the sort of destruction that has the power to break the cycles of life, transformation and regeneration. Only progress is linear. We generate profit. We throw the balance in our favor. We crush and bury.

We suppress wildfire so that we can burn everything else.

Prairie What if prairie is our ancestor, our true inheritance? Or sandstone? Or mastodon fossil? Or Platte River? And why not? Beneath our feet the spiral-toothed shark is crushing shells, the waters swell and recede, a history is written in the limestone and shale that set the foundation that grew the grass that drew the plow. Beneath our feet wildfires burn and grass grows tall and wild. And the soil is alive. The memory of this land is long— the cranes have been landing for millennia, flat water carries the whisper of ice and stone. We see only a future, near at hand and cold. What if we’ve buried our ancestors once and for all— And for what? What if we were to see—really see— Little bluestem. Prairie gentian. Sharp-tailed grouse. Missouri goldenrod. Leadplant. What if we were to really see?

-

-

Writer

Chelsea Steinauer-Scudder

Chelsea Steinauer-Scudder is a writer based in northern New England. As a staff writer for Emergence Magazine, she explores the human relationship to place. Her work has been featured in Crannóg Magazine, Inhabiting the Anthropocene, and the EcoTheo Review. She is currently writing her first book.

-

Linotype Illustrations

Studio Airport

Studio Airport is Bram Broerse and Maurits Wouters. Together with a small team of creatives, they run a design practice based in Utrecht, the Netherlands. The studio has been recognized with international awards for projects such as Hart Island Project (New York), Amsterdam Art Council, and Greenpeace International.

-

Sound Designer and Narration Editor

Ben Suliteanu

Ben Suliteanu is an aspiring filmmaker specializing in editing and sound design. He recently graduated from Stanford University with a bachelor’s degree in science, technology, and society.