Lisa Lee Herrick is a second-generation Hmong American writer, artist, and media specialist who helped produce the film, The Hmong and The Secret War, now available at PBS.org. She is a former television executive and award-nominated news journalist, and a founding member of the LitHop literary festival. Her essays and illustrations have been featured on or are forthcoming from The Rumpus, Food52, The Normal School, and others. She is writing a family memoir about the inheritance and aftermath of trauma, a cookbook, and two graphic novels.

Maria Nguyen is an illustrator based in Toronto. Maria is a staff illustrator for the Global Press Accuracy Network and has worked for The New York Times, Penguin Random House, Simon & Schuster, The Believer Magazine, and others.

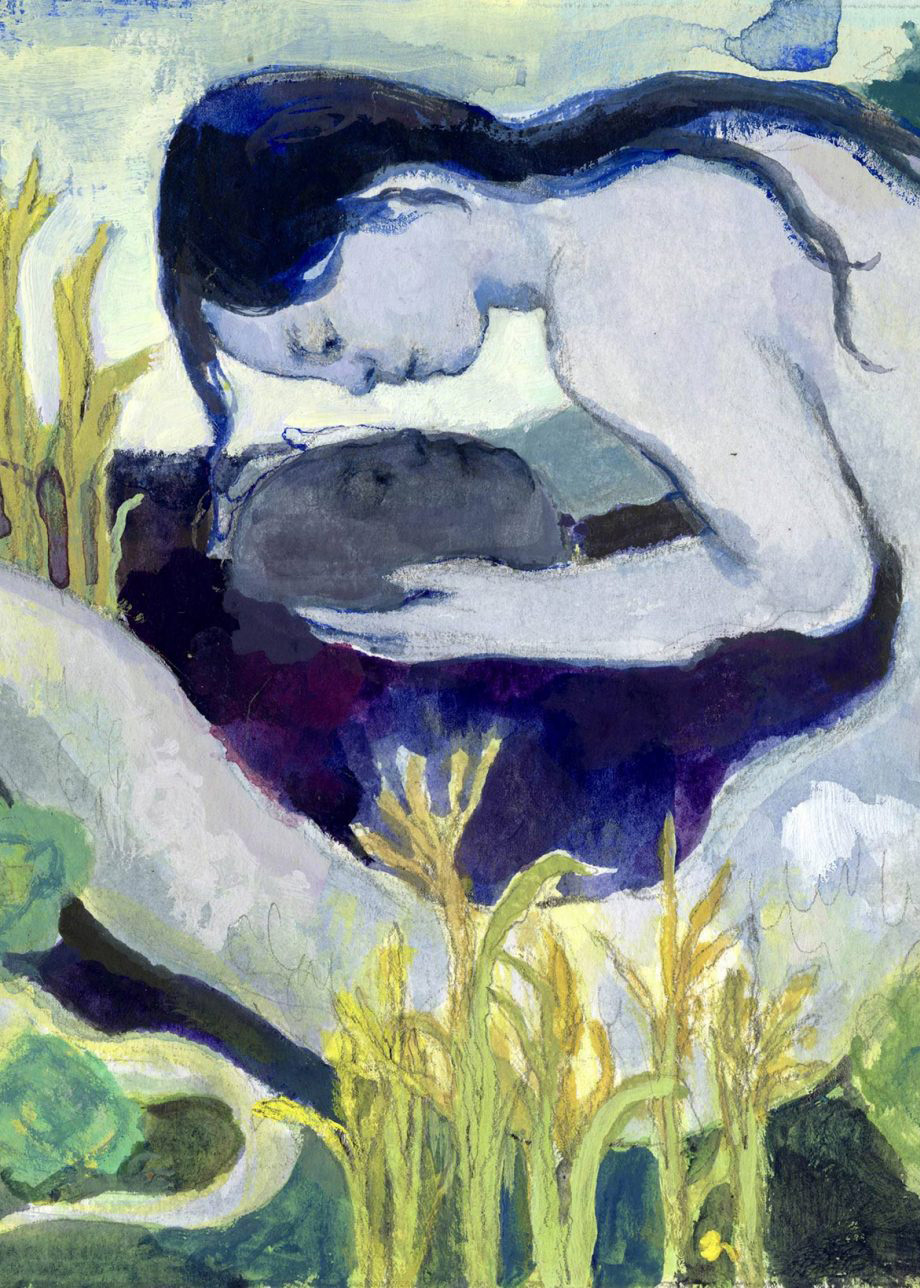

In the storied universe of Hmong cosmology, Squirrel is revered for its ability to outsmart the hunter. In this essay, Lisa Lee Herrick recalls her grandfather—a master squirrel hunter—bringing home a squirrel for spicy hunter’s stew, and how this dish helped unravel a hidden past.

I was born into a storied universe—into a demon cosmology of sound and ether that passed from mouth to ear for generations—and the walls of my father’s house were raised by the excavated bones of ancestors whose names lacked shape or form, save for the pursing lips of the old storytellers. My ancestors died never having held a pen, only shovels and sticks. And, then, guns. We did not have an alphabet until the Christian missionaries arrived. Before then, all words were sacred and committed to memory. My ancestors’ stories traveled by breath alone, like the seeds of future forests carried upon unseen wind. This is how we survived chaos: by speaking the names of our fathers from time immemorial.

Today I struggle with how to tell my family’s story right because the elders are already gone. Their memories haunt me, but their faint shadows will not turn to ink. Their words blur and flee my mind faster than my hands can transgress and write them down. This is how it began: the world hatched from a single butterfly’s egg. This is how we arrived in Laos: we climbed over Frozen Death Mountain—tsoob tuag no—from China many grandfathers ago.

The Hmong people’s path to independence has always been paved with blood: we rebelled against the mythic Huangdi, the Yellow Emperor, before the founding of imperial China; against the Shang, Chou, Han, Tang, Sung, Ming, and Manchu dynasties; against all empires, including the British, the French, and the Japanese. We were called barbarians and savages; rebels and dissidents. We are not that word 苗, or Miao. We are Hmong; to be Hmong means to be free. Qing-dynasty soldiers guillotined our men and boys and posted their heads on our city walls—like grotesque gargoyles—while mounting our women and girls as their Hmong wives. This is why we fled to the mountains: to hide our newborn sons. They chased us to the southernmost reaches of the known kingdom, toward Vietnam, Laos, Thailand, and Myanmar; and the Ming built the Miaojiang Great Wall in Fenghuang, Hunan Province, to keep us out once and for all.

There, in the rarefied air of the remotest mountain peaks, we found our freedom. Kings have always hated us. Only the forest loves us.

We brought with us only the essentials: our words, our ancestors, our hands, and our hunger. We nourished ourselves with stories, soil, rituals, and hunting. We learned to fear Tiger, who is the Demon King of Illusions, and to love Squirrel, who—like us—is chased by his enemies from all directions but never caught: because Squirrel knows how to hide in plain sight. Only the best Hmong hunters tasted Squirrel. We remembered that all things were spirits, even the rocks and the wind, and that the forest always reclaims what you take without gratitude. Never brag or boast about sweet fruits you have found or fresh meat you have snared. The Lord of Nature will trip you, rip out your throat, and eat your three souls. We gave the Lord of Nature an annual offering so that he would bless our villages with fat pigs, chickens, cows, and a bounty of sweet rice and rainbow maize. We grew hemp to coax into cloth, bleached the fibers with ash, and kept our hands busy spinning yarn. Good Hmong daughters are never still. We gathered in front of the fire after meals to spin tales because stories nourished the ancestors living within us. Remember, and your ancestors will catch you when you fall down.

Eventually the world found us again. America turned our hunters into soldiers. The mountains were set ablaze. The wild animals fled the bombs, even Tiger. The forest filled with demons and suicides. There were no more birds, monkeys, or insects singing the hours of the day. Squirrel disappeared, or went extinct. Our mouths grew hollow, like our faces, and our dead sons were wrapped in white sheets and dropped from the sky by metal eagles. Where do you run when you are already on top of the highest mountain? And then we fell.

No one caught us.

If you had asked me when I was a child growing up in California, “Where are you from?” I would have answered “Oregon” because that is where my own story began. If you had pressed on and asked, “No, where are your parents from?” I would have told you that my mother went to high school in Hawai‘i and my father graduated from college in Oregon; therefore, we were Americans, like you.

“No, I mean, where did your ancestors come from, before America?”

I had no idea.

My father’s parents were my only surviving grandparents, and they lived next door to us in an avocado-green house in Merced. When I was ten years old, I was often left in their care while my parents worked in the fields on weekends, picking strawberries and cherry tomatoes for extra grocery money. By then there were six in our immediate family: my parents, me, two younger sisters, and a brother. Our neighborhood was situated on the outskirts of town by Fahrens Park, an enchanted place filled with swimming snakes, topaz-eyed coyotes, squirrels, and owls. The balmy San Joaquin Valley breeze warmed the eucalyptus groves, releasing wave after wave of mentholated incense year-round.

We were all wild then, staying out until sundown; feral as wolves. In the summers, Fahrens Creek dried up and every neighborhood kid waded through clouds of biting gnats and shin-sucking mud to pluck crawdads from the fetid ooze, the little crustaceans’ vermilion pinchers waving futilely. There was a railroad track suspended high above the creek, and the bravest—or most foolish—of us leaped from it into the waist-high muck below. When we pulled these heroes out with an old rope lassoed around the trunk of the crooked willow tree, they emerged with dozens of crawdads clinging to the seams of their pants like ornaments on a Christmas tree. This was how we filled my plastic kiddie pool with hundreds of crawdads one evening: by the next morning half of them had escaped and died in the grass to the delight of crows and scavengers. The survivors were boiled alive inside my grandmother’s tallest pot with chilies, ginger, garlic, lemongrass, cilantro, and fish sauce. My grandfather spooned several helpings of this citrusy, peppery stew over steamed white rice, savoring the tiny fists of pink meat coiled within the tails, and regarded me with a slight smirk. Peculiar girl, not like her mother at all.

Here, at my grandparents’ house, is where the old magic came back to life in small mouthfuls.

Lisa Lee Herrick’s paternal grandparents in Merced, CA, 1990.

Courtesy of the author

My family rarely spoke of the war, or of Laos. Instead I pieced together incomplete and seemingly conflicting clues about our origins from the houses of my parents and grandparents.

My grandparents hung golden-framed photos of King Rama IX and his Queen Sirikit in their hallway. Posters of graceful Thai Khon dancers, hands bent back in the shapes of peacocks and golden deer, retold the epic Ramayana on their kitchen walls, next to a tattered map of Thailand and Laos marked with ballpoint pen. A panoramic poster featuring the sun-starched Dome of the Rock declared their Christian faith.

Their house was damp with the floral-vanilla steam of just-cooked jasmine rice, stewed pork, sticky rice parcels with candied banana centers steamed in banana leaves, herbaceous pandan rice cakes, clarifying ginger broth, and sharp and bitter mustard greens. The tok-tok-tok of my grandmother at her mud-colored ceramic mortar and pestle kept time as she smashed Thai bird chilies with cloves of raw white garlic, the oils atomizing with the unexpected brightness of ripe raspberries and fresh hay before fish sauce rounded the sharp edges with tangy, amber umami and salt. Unlike my parents, my grandparents believed that children should do as they pleased and that adults should always tell the truth. My grandparents raised us to fear nothing, and this is how I learned to string a crossbow, how to shrug the pelt off an animal like a jacket, and how to oil a gun. Still, there were topics I hesitated to ask about because I intuited that the pain was too sharp.

At my parents’ house, my father kept a private library filled with literature on the Vietnam War inside the home office. The door was often locked, and we were not to disturb him unless dinner was ready. Aiyoh! We haven’t lived in Tonkin since Great-Great-Grandfather cut off his own braid and fled his Chinese masters. My mother proudly displayed our baby photos on the wall, but none of herself or her parents and siblings as children. It was as if she had emerged fully formed: womanly and utterly alone in the world. Did your mother tell you how she became an orphan? Too sad, too sad.

We never spoke of her past, until one day, I came home from school with a magazine—the October 1988 issue of National Geographic1—and opened it where the school librarian had cracked the spine. The face of my mother’s father, recently dead, gazed back solemnly from the magazine. It was a photo of his tombstone in Tollhouse Cemetery, located just a little over an hour’s drive away, and my grandfather’s unsmiling face was framed by a small oval embedded into the stone above his name. The photo accompanied a twenty-five-page article chronicling Hmong Americans’ progress in America since the first wave of refugees arrived ten years before. It had not occurred to me, until then, that we had come from a particular place or people. Hmong, Lao, Thai, Vietnamese, Chinese, American: weren’t we all those things? My confusion and my parents’ silence were linked.

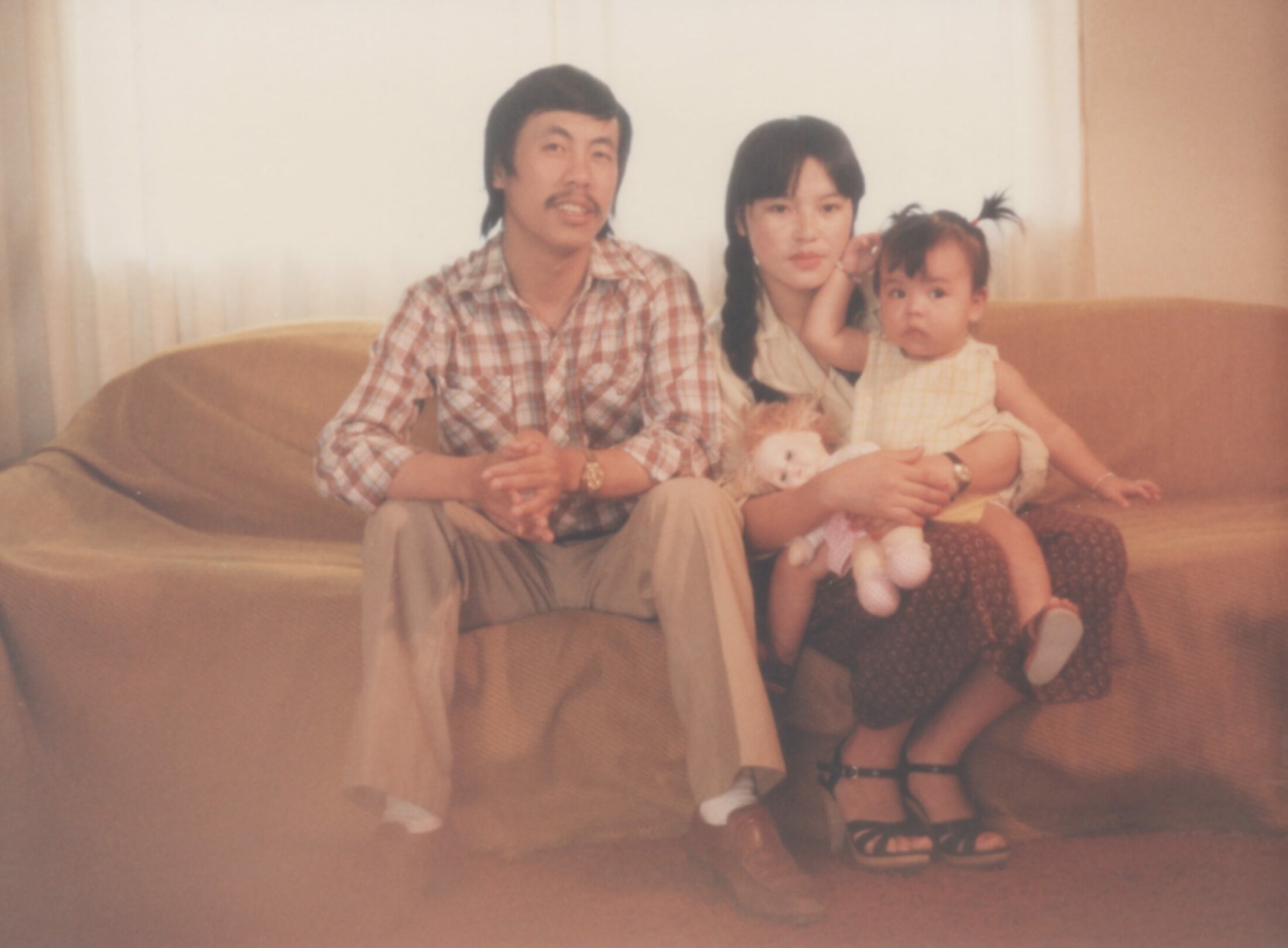

Lisa Lee Herrick with her parents, 1982.

Courtesy of the author

None of the history textbooks at school mentioned the Hmong or why we were here. It was as if we had sprouted from the earth overnight, like weeds pushing through cracks in the sidewalk. Yet, inexplicable as our sudden arrival was, here we were, a makeshift Hmong village centered on the local Evangelical Christian church in Merced—a quaint Main Street USA kind of picture-postcard town in California’s agricultural heartland, flanked on both sides by the ridges of the Sierra Nevada and the Coast Range. This is where we landed as seeds from the wind and where we embedded our roots.

Our community’s regular attendance at the Hmong Evangelical church was a socially convenient excuse to maintain the old customs without arousing suspicion: We met twice a week to discuss clan disputes; learned to read and speak Hmong on Saturdays; brokered marriages between families; celebrated births; planned funerals and butchered animals; and organized the New Year festival, noj peb caug, which means “to eat for thirty days.” We shared organic produce from backyard gardens in the church courtyard and swapped herbal medicines and home-brewed tinctures in the parking lot. As long as we celebrated Jesus Christ every Christmas, nobody interrupted us. The church was also where Hmong men could plan fishing and hunting trips, and this is possibly the only reason why my grandfather had a perfect attendance record.

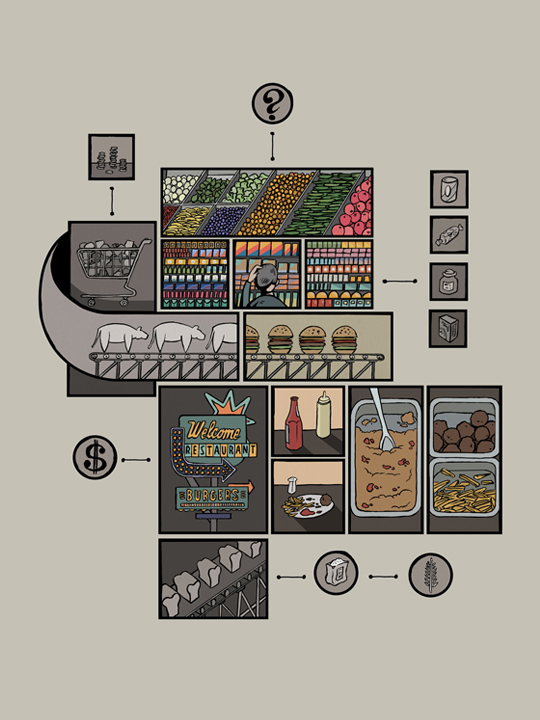

Christians have been instrumental in the Hmong’s connection to the modern world. Catholic missionaries began arriving in mountaintop villages in the nineteenth century, and eventually they created an alphabet for us so that we could study their holy literature. Many Christian families and churches sponsored Hmong refugees after 1975, dispersing them on every continent except Antarctica and Africa.2 The Christians had noble intentions, even though many of them considered their foreign guests exotic and childlike. Perhaps many Hmong converted to Christianity merely as a matter of convenience—a polite gesture of simple gratitude for the Americans who opened their cramped houses to entire families, sometimes up to three generations in one room. Many of their host families fed them sandwiches and instant ramen noodles, while Hmong refugees were quickly learning that, in America, there were strict rules and regulations against catching your own dinner from forests and city parks.

Now that Grandfather had his own home—a cozy little house with moss-green carpet and gold-flecked linoleum floors erected on the soft bend of a tree-lined avenue—he caught and ate whatever he pleased. I spent many afternoons watching Grandmother shredding herbs from her garden—scallions, cilantro, dill, culantro, and spearmint—and snapping fat toes of ginger into her boiling cauldron. Grandmother knotted thin blades of lemongrass and they disappeared into the soup. Meanwhile, Grandfather dissected the beast of the day at the dining room table with his machete, an albatross wing of hand-polished steel, which smeared rose petals of blood and gore into the tablecloth. This was their natural rhythm: preparing meals in separate rooms, a luxury compared with the crowded single-room, dirt-floor hut they’d all shared in the Ban Vinai refugee camp—which my father helped build—back in Thailand. Today’s menu was his childhood favorite: squirrel, naas, cooked in spicy Hmong hunter’s stew.

Without their gloriously full and bushy tails, squirrels look exactly like giant sewer rats. Grandfather bit his lower lip delightedly, chuckling how American squirrels were positively fat compared with their Laotian cousins. “Same for you,” he said, laughing, pinching the fleshy back of my arm. “American girls. So chubby, so tall. Big bones. Too much milk and peanut butter.”

I watched him carefully peel the black, charred skin off the small body and guillotine the head. He held up the strips for me to see: the burned hair had powdered to ash. “This is the most delicious part,” he said. “This we slice thin, like noodles.”

“Squirrel is very smart for a small animal,” Grandfather continued, tapping the sooty, walnut-sized skull with the butt of his machete handle. “You must outsmart him. When he is thinking, his tail gets very excited, like this,” he said, fluttering his fingers in the air.

Grandfather said that in Laos the squirrels were very beautiful, with many colors and stripes, and that they sang to one another at dawn. Some squirrels were enormous, like the cream-colored giant squirrel (Ratufa affinis) and the black giant squirrel (Ratufa bicolor), and they were like ghosts leaping through the trees. The Hmong called them maab because they were as big as foxes. The species that both Lao and Hmong loved to eat most was the Pallas’s squirrel (Calloscius erythraeus), whose belly glowed bright red like a split ripe papaya.

Only skilled hunters successfully hunted squirrel in Laos. They used wooden crossbows and never the flintlock rifles or other guns. When a Hmong hunter had a successful kill, he first dipped the tip of the wooden tiller into the bleeding carcass, then repeatedly coated the weapon with tufts of hand-pulled fur or soft covert feathers until each layer formed a filthy burl. In time, a scab of trophy souvenirs hardened over the tiller, proving that this weapon was blessed by the spirits to always aim true. Young boys learned how to hunt squirrels by shooting Indochinese ground squirrels (Menetes berdmorei), first because they were pests that ate the rice and corn. These tiny squirrels had black stripes along their ribs and were unafraid of people, so young hunters could practice hunting using lightweight bamboo crossbows and arrows thin as reeds.

We brought with us only the essentials: our words, our ancestors, our hands, and our hunger.

Once, my father told me that he and his oldest brother shot an arrow that pinned the hind legs of a red-cheeked squirrel together so tightly that it couldn’t run away. It was beginner’s luck. The squirrel tumbled to the ground and rolled onto its side, whimpering chic-chic-chic while its white belly heaved and sighed. I asked my father what he did next.

“I did what you’re supposed to do,” he said matter-of-factly. “I took my own arrow, inserted the sharp tip inside the squirrel’s ear, and pushed it all the way in. That’s what the Hmong do if the animal is still alive. We pierce its brain to kill it quickly, then mark the ground around it with its blood to show others where it died.” This is the rule of the forest: everything is spirit, and death must be honorable.

“Your grandfather was a very dedicated hunter,” my father told me, “so we always had meat even though we were very poor. Many people only got to eat chicken once or twice a year, but we ate monkeys, deer, pheasants, partridges, fish, and especially squirrels all year long.”

I remembered my grandfather’s sly smirk as he ate the crawdads I’d plucked from Fahrens Creek.

“Hunting Squirrel is a game—who will win?” Grandfather continued. “Who is smarter? Me?” He tapped his forehead with his callused index finger. “Or him?”

“Squirrel is a ghost: you think you hear his feet scratch-scratch-scratching the tree in front of you, when he is already above your head, watching you closely with eyes so round that he sees everything. He is like people: he makes plans and plays pretend. That is why, if you can kill Squirrel, you must eat every part. If you waste the meat, you dishonor his surrender.”

My grandmother yelled from the kitchen. The pot was boiling over, and so was she. Unlike Grandfather, she hated the smell of stewed squirrel. I remember it, too: its musky, sweaty stink of old leather, rancid cooking grease, pine-tree sap, wet fungus, and muddy putrefaction.

“I only cook this stew because your grandfather craved it all the time in Ban Vinai,” she complained. “‘When we get out of here,’ he’d say, ‘when we return to the village, I’m going to eat squirrel every day!’ I told him, ‘Idiot! You will have to savor it in the afterlife because we are all dying here.’ Little did I know that your father would help us all escape to America, and now I must cook with every window open, because your grandfather brings too much meat home. I’ve been cooking squirrels so long that I’m afraid the smell will be on my ghost, but I do it because I know it reminds your grandfather of when he was a young man, and life before the war, when your father and uncles were just boys.”

Sometimes when Grandfather ranted about returning to Laos and finding the ancestral village on Phou Bia, Grandmother would point out the window and say, “Look! This is our home now: America. Stop dreaming of impossible things.”

In Laos, Grandfather said, you didn’t need a license to hunt or fish because Hmong lived so high up in the mountains that the governments did not care, and the forest was unclaimed except by the Lord of Nature and the cosmology of demons. This was why Grandfather said that hunting seasons and permits were useless rules because the only true trespass was not honoring the proper rites; the worst offense was killing for pleasure, rather than for hunger or self-defense. If you crossed a boundary where evil spirits, wild animals, and bad men could attack you, then you had to call upon your ancestors to protect you.

While my parents pretended to remember nothing, Grandfather told me stories at the dining room table of how families fled barefoot toward Sayaboury, sprinting to the edge of the Laos-Thailand border, after the Americans suddenly evacuated their own personnel from Long Cheng air base and left everyone else on the mountain. He told me how the mud sucked at his heels while bullets zipped like heat-maddened flies, how mothers pressed babies to their breasts to muffle cries that would have given them away to the snipers in the trees. Desperate parents rubbed sticky black opium tar on their children’s gums to dull their senses. The most merciful parents rubbed too much and laid their children down at the foot of a sacred tree to slip from dreams into eternal slumber, and kept running. There was no time for burial rites. The children’s disembodied spirits would always be orphaned from their ancestors. This is why, Grandfather said, if you are hunting alone in the forest and hear a child laughing behind you, you must quickly roll a ball of sweet grass and leave this offering on the ground for the ghost child to suckle, then leave without looking back, not even from the corner of your eye.

This is the rule of the forest: everything is spirit, and death must be honorable.

Grandfather continued to hunt because he was convinced that American foods were poisonous.

“Why do people in this country get so sick even though food is overflowing?” he asked. “In Laos, we did not even have soap to wash our hands, but the animals drank water and ate food that was so clean, you could drink their blood if you were starving.”

The Hmong who were born here, Grandfather said, smelled American, like milk that had soured. He refused to drink the stuff, saying that he could never forget watching the family ox’s drooping teats dragging through the muddy rice paddy, year after year, barbed with mosquitoes and seeping with infection.

He refused to buy fruits and vegetables from the grocery store, saying that the produce was either flavorless or nearly rotten. He boiled tap water and chilled it in the fridge for drinking. He tore out the backyard, planted a vegetable-and-herb garden for my grandmother, then built a wooden hutch for rabbits and wove a wire dome for chickens. I remember those chickens boiled in lemongrass soup, their goose-bumped flesh rich and savory from eating fat, green caterpillars all summer. The rabbits were much loved; then they, too, ended up in the pot with lemongrass and ginger. At my grandparents’ house, we ate with our hands, which were the same hands we used to tear the animals apart: an intimate act that reminded us of the thin line between horror and beauty. This is why Grandfather disliked eating hamburgers, calling it unclean to swallow so many animals ground into a paste at a factory with all their shit, piss, and fear.

Never forget that the world is alive. Even mountains may move.

In America, Grandfather said, everything is upside down: He is the child now, and we do not respect him because he cannot speak the words correctly. In America, you can lose everything because you have debts, even after you die. In America, he said, the squirrels don’t sing. They are drab and eat out of garbage cans. It is too quiet here, except for the constant roar of traffic—airplanes above you, subways below, and the people always pointing at you, laughing in your face. He was afraid that, because he had left his village so suddenly in the night, his ancestors would not be able to find his spirit if he died in America. If the ancestors could not find him, he said, his spirit would always be a hungry ghost. And if we forget who we are, who will protect us then? The forest is desecrated. No one loves us here.

“Your face is Hmong,” my grandfather said, “but your mouth is American. When you forget me, I will have lost your heart, too. You will no longer be Hmong. This is why you must eat the squirrel stew. It’s all that we have left to give to you.”

At first I sat obediently at the head of the dining table and watched Grandmother ladle the bright-red stew over a mound of white rice in my bowl; but my stomach flexed and I couldn’t bring myself to eat it. The meat was dark purple, floating beside orange globules of smoky fat that smelled of old blood and singed fur. It smelled like violence, and it frightened me. I excused myself, and opening the refrigerator door, pretended to look for a drink as I reached into the vegetable drawer, past a head of lettuce, for my aunt’s secret Halloween-candy stash. My hand squeezed down on something cold and gelatinous: a plastic-wrapped bullfrog with sunken eyes, cold and clammy, like mummified gelatin. I recoiled in disgust, but I was determined to find something else to eat and avoid that squirrel stew. I raised myself up on tiptoe and opened the freezer door, and a frozen squirrel—eyes pulled back into slits, teeth bared and grinning—slid down a sheet of ice and hammered me right between the eyes.

It knocked me out, and I hit the floor.

In The Mong Oral Tradition: Cultural Memory in the Absence of Written Language, Yer J. Thao writes that if a Hmong person no longer values Hmong traditions, he or she no longer values spirits as protectors. Feeling ashamed of one’s traditions means dishonor to the ancestors. The souls and spirits from outside the family are considered evil; they will not protect you—they will haunt you. This is the Hmong cosmology.3

Remember, and we will catch you when you fall down.

This is why you must eat the squirrel stew. It’s all that we have left to give to you.

As Hmong, we can trace our origins to the Yellow River basin of central China.

This is based on our patrilineage, oral histories, documentation in classic Chinese literature, and, now, genetics. Some archaeologists and linguists assert that our presence in China started as early as 5000 BCE.

What is certain is that many Hmong rebels fled China for Southeast Asia by the early 1800s to escape persecution and racial cleansing by the imperial state.

My mother’s and father’s families settled in Laos at least a hundred years before the country finally gained its independence from France in 1954. My father’s clan—the Lys—had hoped that this independence would grant their sons the opportunity to become teachers and political leaders like Phagna Lyfoung Touby, who was leader of the Ly clan and one of the first Hmong to be educated and then to serve as minister to the king. My father was studying at the French lycée in Vientiane, the capital city of Laos, while my mother, on the other hand, lived in Long Cheng—the second-largest city in Laos at the time, atop the country’s highest mountain, Phou Bia, in Xieng Khouang Province. The North Vietnamese had occupied a section of that province for several years, considering it their territory. Their continued presence contributed to the rise of communist control, ultimately culminating in what would become a fifteen-year civil war. My mother saw the bombs and gunfire raging long after the official cease-fire in 1973; the war ended only with the fall of Vientiane in 1975.4

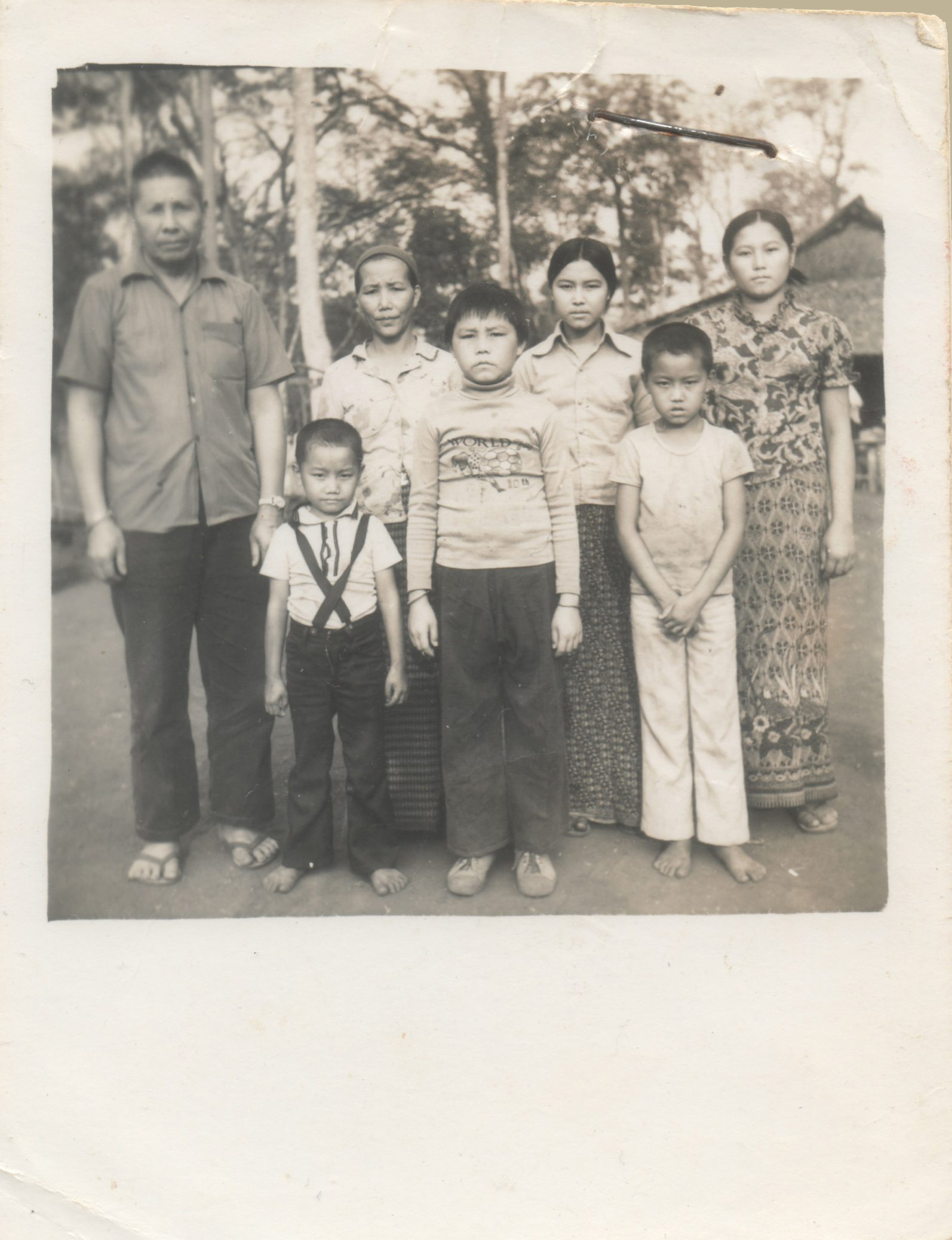

Lisa Lee Herrick’s mother and family, Ban Vinai Refugee Camp in Thailand, 1978.

Courtesy of the author

My father was one of about 350 Hmong students studying at the only national educational institution. He had wanted to become a teacher, but as a relative of Phagna Lyfoung Touby and a Christian, my father feared he would be declared an enemy of the communist and atheist Pathet Lao state. When an unidentified motorcyclist threw a live grenade into Prince Boun Om Na Champassak’s car in 1975, killing him,5 the message was clear: death was already here, and it was time to leave. My father held private gatherings with friends to pray and to plan his family’s safe exit from Laos, and they decided that the best way to escape to Thailand was to use their student-identification cards, which allowed them to travel wherever they liked without being questioned.

When my father finally did arrive in Thailand, he had nothing more to study and no one would hire him, so he started clearing the forests to build Ban Vinai, the refugee camp that would come to house more than forty-five thousand Hmong refugees6 until it was finally closed by the Royal Thai Government in 1992.7 He stayed there for only a year, and then he and his entire side of the family were flown to Oregon to live in a little house with the family of a kindhearted French high school teacher. My mother and her family ended up waiting in Ban Vinai for four years for a sponsor. By the time she and her older sister finally landed in Hawai‘i, she could no longer speak. My mother said that she had forgotten her entire life before Ban Vinai, her life before the war arrived, her girlhood, even the sound of her mother’s voice. She didn’t speak for months, and she refused to eat. She arrived in America an empty shell. In Hmong, we say that you can be so scared that your spirit falls out of your body. Poob plig. Only a shaman can heal this.

For a long time, I was her picture window into the girlhood she had locked away from herself. I described my days of going to school and talking to friends, watching television, reading books, and eating strange foods like chocolate milk and string cheese. My mother’s resentment and envy were a black stain in our house. She often slept on the couch after I came home from high school, complaining of migraines, so I learned how to fillet whole fish, stir-fry the meat, flash-sauté the mustard greens, and serve the rice from the center of the table. This was before we had names for her pain: depression, anxiety, PTSD. In Hmong we say, “Kev ntxhov siab”: having a tangled heart.

Never forget that the world is alive. Even mountains may move.

When I was a little girl, back when the world seemed as big and deep as midnight, I rode with my father to Applegate Park in Merced. He once asked me to sit on the bench and keep watch for police or park rangers while he rummaged through the trash for picnic leftovers and other half-eaten morsels. He had been unemployed for months and couldn’t face my mother any longer. I remember, even now, the giddy smile on his face when he fished out a McDonald’s bag and found two whole cheeseburgers still in their paper casing. They were nearly perfect except for one small bite. He flicked off the dirt with the backs of his fingers, pulled out the meat patty, and handed it to me while pocketing the other for my mother to eat. Embarrassed for him, I tore my patty in half and handed the large piece to him. We chewed in silence, my father quietly sniffing back tears.

As we sat there on the park bench, a ruddy squirrel with tufted ears crept toward us, asking for permission to approach. My father pinched a piece of bread with two fingers and held it toward the squirrel. The squirrel stood on its haunches, considering our offer.

“The squirrels in America are so different from the ones in Laos,” he said. “Here, they will approach you if you are gentle and still. They are bold and fearless.” The little scavenger inched forward, its tail a question mark, then a comma.

“In Laos, they can smell their own death and run away from everything,” my father said, slowly lowering his hand to the ground.

“In many ways, we are exactly like them. We, too, know death too much.” The squirrel bounded up to my father’s fingers, ripped the bread away, and scampered up the nearest tree. My father smiled and leaned back into the park bench.

The war that brought my family to America is not the war on the tip of your tongue.

Ours was the Secret War, a Laotian civil war, which was not the same as the Vietnam War (or the American War, as the Vietnamese called it)—although both raged side by side starting in the 1960s. When the communist North Vietnamese Army refused to withdraw over seven thousand troops from neutral Laos, America feared a “domino effect,” the unmitigated spread of communism throughout Southeast Asia. In December 1959 the Central Intelligence Agency clandestinely recruited General Vang Pao—my mother’s uncle from the Vang clan—and began training Hmong hunters of all ages in guerrilla tactics.8 This was preparation to fight a secret war that started in the mountains, the mountains where my mother lived while my father was at the Lycée Français in the South. None of the American-history textbooks from my childhood mentioned this because the CIA documents detailing these operations remained secret themselves until 2008.

It was the Hmong secret army who rescued downed American pilots, flew planes on covert missions, fought ground battles, sabotaged the Vietcong along the Ho Chi Minh Trail, radioed intel, and endured the highest casualties. And then they were left behind, along with many Hmong military families, when the Americans retreated in 1975 and emergency-evacuated their personnel to Thailand. My mother lived through all of this in Long Cheng, the city atop the highest mountain, which was also a secret air base that did not exist on any map at the time.

The Secret War would become the largest CIA paramilitary operation in history. For nine years, between 1964 and 1973, the United States ran over 580,000 bombing missions, equal to a planeload of bombs every eight minutes, twenty-four hours a day—making Laos the most heavily bombed country per capita in human history.9 Most of the bombs were dropped near the Ho Chi Minh Trail and the Laos-Vietnam border in Xieng Khouang Province,10 where my parents’ families lived. Today there are an estimated eighty million unexploded ordnances still dotting the landscape,11 hidden in the underbrush or just below the topsoil, waiting to be triggered by a wayward foot or curious hand. There are even some bands of Hmong guerrilla fighters—Hmoob caub fab—still hiding in the jungle near Phou Bia, unaware that the Secret War between CIA-backed SGUs (special guerrilla units) and the Pathet Lao is long over.12 Some are waiting, unsure whether to escape or surrender over forty years later. This is American history, too.

Everything is upside down in America.

My grandfather’s sudden death in 2007 imploded my father’s family, and each sibling pointed a finger at the other. He had suffered a heart attack in the bathroom at my parents’ house, slipped to the hard linoleum floor, and died in my brother’s arms that June. I was twenty-five years old.

At the funeral, I pushed Grandmother in her wheelchair and listened to her muffled sobbing as she cursed my grandfather for leaving her so bereft. We watched the ground enfold him, scoop by scoop. Grandmother sang a funeral poem, hiccuping through the syllables, and I gazed at my grown siblings and cousins, not recognizing many of them at all. Grandmother asked Grandfather to forgive her for not granting his one wish: to be buried back in the forest he loved most, back in Laos, with his many grandfathers. She begged him not to return as a hungry ghost—furious for being cut apart from his ancestors—and apologized for losing hope so often. She tossed the flowers atop his casket, then asked me to push her under the shade. Two cows had been butchered for the funeral feast. I know my grandfather would have preferred squirrel. The meat is leaner, lower cholesterol.

A homesickness for the sights, smells, and sounds of my girlhood took root within me. For the first time in my adult life, I began to miss my grandmother’s sunny kitchen, her face veiled by steaming pots, and even my grandfather’s bloodstained dining room table, filled with squirrel parts and bushmeat. I missed cooking dinner for my parents and siblings, along with the prickling sensation of burning chilies mingled with fish sauce, tamarind pulp, and fermented blue crab on my tongue.

Never forget that the world is alive. Even mountains may move.

My father still laughs, recalling how, when Grandfather arrived at one particular hosted home, he grew sick of sharing one packet of instant ramen noodles among four or more people a day, and he craved fresh meat so intensely that he snared an opossum from the local park, using a wooden trigger-release trap, and lassoed the marsupial’s pink-toed foot with a string, suspending the hissing, thrashing beast from a tree branch until a rock cracked its skull. Grandfather had rushed back with the creature hidden in his jacket and boiled it whole in a pot. Their hostess, a French high school teacher, was horrified to find the pink, curly tail bubbling on the stove, and she tossed the entire pot out into the trash bin, declaring that everyone was eating only peanut butter sandwiches until further notice.

My grandfather, who was the second of three warrior brothers, did not understand her taboos: he was born at the end of World War I, already a man when the Japanese invaded French Indochina in 1940; married a headstrong woman from the Yang clan and served as the chief of Xieng Khouang village for twenty years; raised nine children; pushed the Vietcong back to the border; and then fled the country. His entire life had been spent in war—providing meat and fighting for survival was all he knew. The Lord of Nature gave people mouths to eat and to praise the spirits. Grandfather muttered bitterly that surely the Lord of Nature would curse such a wasteful woman to avenge his slow starvation.

This is the rule of the forest: everything is spirit, and death must be honorable.

My father smiles, remembering how strong and tall Grandfather was when he was a young man and chief of the village. He remembers that Grandfather’s hair was long and raven black, and he moved like a panther through the trees with his long limbs and spry feet. His favorite thing to do, when simply exploring the jungle, was to stalk wild pigs and catch them bare-handed in his arms. He was like the Lord of Nature himself, walking between the trees unseen but felt everywhere. I like to imagine that the ancestors have been merciful and returned his spirit to that otherworld, and that his voice now joins the chorus keeping all the hours of the day into night under the canopy of the infinite forest.

We are Hmong; to be Hmong means to be free.

- Spencer Sherman and Dick Swanson, “The Hmong in America: Laotian Refugees in the ‘Land of the Giants,’” National Geographic 174, no. 4 (October 1988): 586–610.

- Yer J. Thao, The Mong Oral Tradition: Cultural Memory in the Absence of Written Language (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2006), 11–16, 54–55, 82–85.

- Thao, 3–4.

- The North Vietnamese had occupied a section of Xieng Khouang Province for several years before crossing the Laos border in the late 1950s to build the Ho Chi Minh Trail. As supporters of the communist Pathet Lao, who were opposed the Royal Lao Government, the North Vietnamese played a critical role in what became the Laotian Civil War, which ended only when the Pathet Lao took control of the Laos government in 1975. https://alphahistory.com/vietnamwar/laos-during-vietnam-war/.

- Gayle L. Morrison, Sky is Falling: An Oral History of the CIA’s Evacuation for the Hmong from Laos (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 1999): 40.

- David Moffat and Wendy Walker, “Hmong Children: A Changing World in Ban Vinai,” Cultural Survival (December 1986), www.culturalsurvival.org/publications/cultural-survival-quarterly/hmong-children-changing-world-ban-vinai.

- “The Split Horn,” Public Broadcasting Service, www.pbs.org/splithorn/story1.html.

- Keith Quincy, Hmong: History of a People (Cheney, Washington: Eastern Washington University Press, 1988): 170–188.

- “Secret War in Laos,” Legacies of War, http://legaciesofwar.org/about-laos/secret-war-laos/.

- Quincy, 189–211.

- Padraic Convery, “200 Years to Go Before Laos Is Cleared of Unexploded US Bombs from Vietnam War Era,” South China Morning Post, November 16, 2018, www.scmp.com/magazines/post-magazine/long-reads/article/2173220/200-years-go-laos-cleared-unexploded-us-bombs.

- “Hmong: Alarming Crackdown on the ChaoFa in LPDR,” Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization (UNPO), October 29, 2018, http://unpo.org/article/21186

Further Reading

Keith Quincy, Hmong: History of a People (Cheney, Washington: Eastern Washington University Press, 1988), ix–111.

Louisa Schein, Minority Rules: The Miao and the Feminine in China’s Cultural Politics (Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, 2000), 96–97.

“South Great Wall,” China Highlights, last modified June 7, 2018, https://www.chinahighlights.com/fenghuang/attraction/south-great-wall.htm.

Jane Hamilton-Merritt, Tragic Mountains: The Hmong, the Americans, and the Secret Wars for Laos, 1942–1992 (Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 1999), xxiii–xxvi.[/footnote] Some are waiting, unsure whether to escape or surrender over forty years later. This is American history, too.