Kalyanee Mam is a Cambodian-American filmmaker whose award-winning work is focused on art and advocacy. Her debut documentary feature, A River Changes Course, won the World Cinema Grand Jury Prize for Documentary at the 2013 Sundance Film Festival and the Golden Gate Award for Best Feature Documentary at the San Francisco International Film Festival. Her other works include the documentary shorts Lost World, Fight for Areng Valley, Between Earth & Sky, and Cries of Our Ancestors. She has also worked as a cinematographer and associate producer on the 2011 Oscar-winning documentary Inside Job. She is currently working on a new feature documentary, The Fire and the Bird’s Nest.

Tracing her father’s struggle for agency and acceptance in the United States after her family fled the Khmer Rouge regime in Cambodia, Kalyanee Mam reflects on the false promise of the American Dream and the deep belonging she finds in the wisdom of her ancestors.

Each year it becomes increasingly difficult to return home from the mountains and readjust to the world we’ve left behind. This year proved even more challenging.

This summer, my husband, David, and I made our annual pilgrimage to the Sierra Nevada in California, this time to the Eastern Sierra, the land of the Paiute. We met fourteen years ago in Yosemite and have been returning every year since then. Each year, we look forward to greeting the trees, shrubs, and flowers that pop up every summer along the slopes and trails like long lost friends helping to guide us along our journey. We know that where the willows grow, there will be water nearby; where the phlox and buckwheat bloom, it will be rocky and dry; where the foxtail and whitebark pines bend their bodies, it will be high and windy, their gnarled trunks a testament to the harsh conditions that surround them. Each year, we look forward to our multiday hikes into the backcountry and sleeping in our tent beneath the stars, nestled and embraced by silence and solitude. Each year, we look forward to learning and observing all of the changes in this place that has become our home away from home.

In the mountains and on this land, I feel at home and one with the world around me without having to give up who I am. We sleep on the ground, the earth our pillow, the star-studded sky hanging above us. We drink water from and bathe in the lakes and streams. With each breath and exhalation, we establish a connection with the plants and trees around us. My existence as a solitary body seeking worth, truth, and meaning fades away. There is no mirror nearby to reflect my fears and insecurities, my wants and desires, or my hopes and dreams. There is only silence and beauty, echoing the beauty and stillness of my heart. In the mountains I am reminded of something my dear spirit sister Reem Sav See (whom I lived with for several years while filming her and her family) once told me as we sat in a thatched hut, surrounded by the ripening rice fields of southwestern Cambodia’s Areng Valley, looking out at the mountainous jungle shrouded in mist: “Nothing belongs to me; yet I belong to everything.”

I reflect on why I feel so at home in the mountains and yet so lost here at home. I realize that in this society I do not feel whole, nor do I feel I am part of a greater whole. I feel I must constantly adjust, fit in, and become someone better—or risk grave consequences. This feeling, which I have carried with me all my life, has a history.

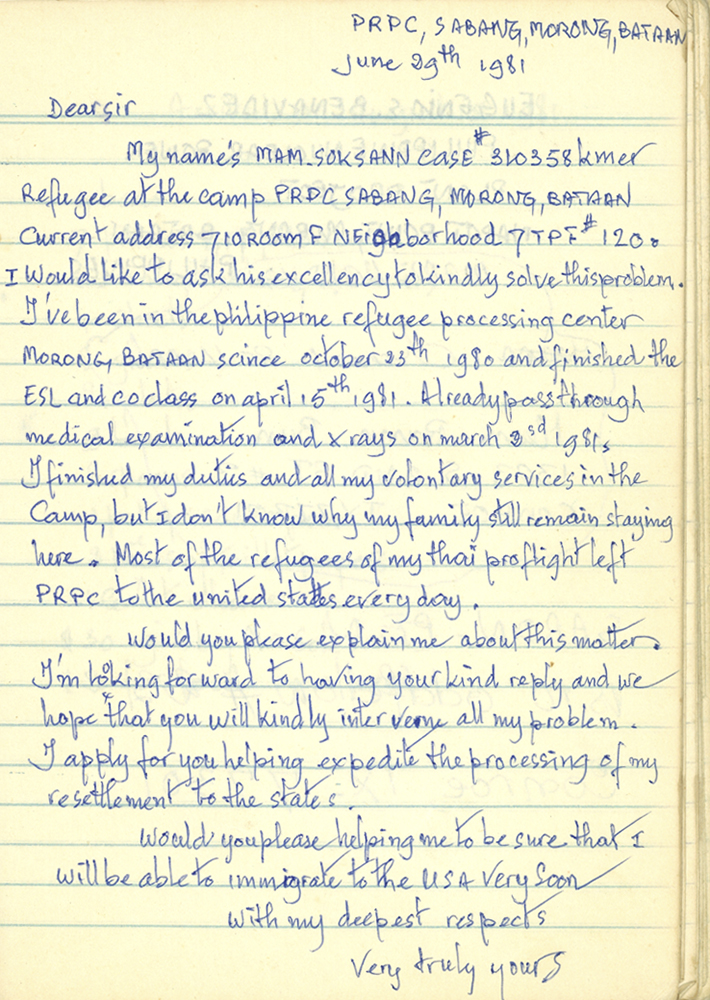

My family’s journey to this country and our process of fitting in began with a letter my father wrote to the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on June 29, 1981.

My family and I had just fled the Khmer Rouge regime. We left the refugee camps in Thailand and were temporarily placed in a refugee processing center in the Philippines to await permanent resettlement in the United States. Over eight months had passed, and we were still waiting.

My father humbly directed the letter to a “Dear Sir,” requesting “his excellency” to “kindly solve the problem.” He outlined all the prerequisites he had successfully completed—medical examinations and x-rays, an English as a Second Language class, and “duties and responsibilities in the camp.” He questioned why, after completing these prerequisites, we still remained in the camp while so many other families who had been on the same flight with us from Thailand to the Philippines were already resettled. He wanted to understand why, having done everything he could to ensure we would be granted admission, we were still denied. Despite the humble nature of his letter, my father was articulate and firm with his request.

“Would you please explain me about this matter?” he asked.

However, his tone remained respectful and even pleading: “I’m looking forward to having your kind reply, and we hope that you will kindly intervene all my problem.… Would you please help me to be sure that I will be able to immigrate to the USA very soon?”

He ended the letter: “With my deepest respects. Very truly yours.”

During the Khmer Rouge regime, which claimed the lives of nearly two million people, my father learned that our lives could be taken from us at any moment. He hid his eyeglasses; my mother stashed away old baby photographs of my sister Sophaline and my brother Makkara and sewed precious gemstones and gold jewelry into the seams of her pants. We could have nothing in our possession that would reveal we were educated or even middle class.

Later, when we applied for admission to the United States, my father also learned that our lives were not ours. It was in someone else’s hands to grant or deny us entry. And if he did not abide by the rules—learn English, pass his medical exams, and prove that he could be a good citizen—he would fail. He learned these lessons over and over again once we arrived in the United States as he struggled to pursue what was sold to him and to so many other immigrant and refugee families: the “American Dream.”

The American Dream has often been defined as a struggle for opportunities which are granted to those willing to pull themselves up by their bootstraps and fight for success. This dream has also been defined as a boundless pursuit of happiness, wealth, power, and acceptance—oftentimes, these pursuits are conflated with one another.

One could say that we should be grateful for the opportunity to flee the nightmare that was the Khmer Rouge. But that way of thinking is embedded in hypocrisy: if Cambodia had never been colonized by France, and if the United States government hadn’t bombed our homeland and supported a fascist regime, we would not have become refugees. In pursuing this American Dream, we were plunged into the depths of a more subtle but equally powerful nightmare. We fled a genocide in Cambodia only to enter into another genocide of our ancestry, our identity, and the core being of who we are.

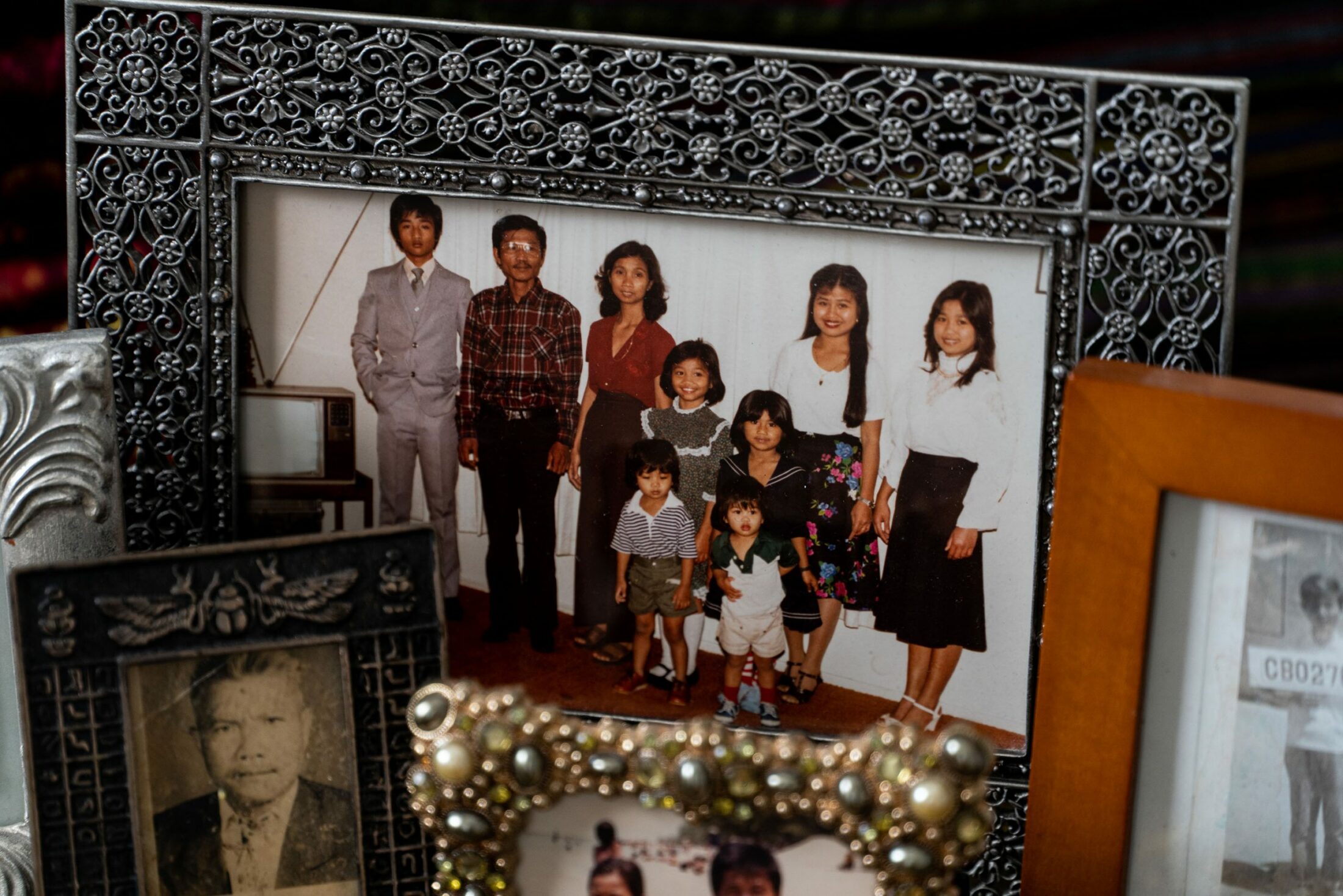

My family and I arrived in this country with the help of the International Rescue Committee and local church organizations in Houston, Texas. When we first landed, the church groups set up our family of nine in a four-bedroom house, which we shared with seven other Cambodian families. They gave us clothes; my mother wishes she still had them today. She said they were such good quality—not like the clothes we have now. The shirts, pants, dresses, and shoes were usually worn only once or twice by people who could afford to give their clothes away to those less fortunate and buy new ones. Everywhere we went, we were taught to be grateful to the people who helped us. I learned to pick up subtle cues from my parents: to bow my head and nod in agreement like my father and to smile and laugh like my mother, even at things we didn’t really understand. All of this was just to show that we were agreeable and meant no harm, and that we didn’t deserve to be sent back.

We later moved to a small two-bedroom apartment. The building stood near an affluent community in Houston called River Oaks. My sister Phalkun and I would walk home from school and admire the towering mansions we passed by, picking pecans off the ground that no one in the neighborhood picked or ate. We climbed the magnolia trees that lined immaculate front lawns and dipped our faces into the enormous, silky, lemon-scented white blossoms. The owners would come out and wag their fingers at us. “You monkeys come down now, ya hear! Don’t you know you can’t climb other people’s trees?”

In Houston, my father got his first American job, working at City Mapping Company, while my mother woke up early in the morning to pick trash with other Cambodian refugees. She even remembers picking up a few hundred-dollar bills that were floating beside the highway.

Not long after, my parents saved up enough money to buy our first American car: a used Chevy Chevelle. My eldest brother, Makkara, says that was the best car ever made. It was slick, shiny, and blue. It drove like a dream.

The owner of City Mapping Company took a strong liking to my father, who was easygoing, diligent, and hardworking. He thought of my father like a son. The owner’s brother was not pleased. He took a baseball bat and smashed the windows of our first car, slashed the tires, and told my father he didn’t deserve to be here or to have such a nice car. My father was devastated. When he came home that evening, my mother saw the broken windows. My father was silent; my mother didn’t ask. He might have been angry, but he didn’t express it. He knew there was nothing he could do. No matter how much he bowed his head, no matter how much my mother smiled, they were not welcome here—and neither were their children.

We didn’t remain in Texas too long after that. We received a phone call from friends urging us to move out to California, where there were plenty of jobs and educational opportunities for the children. My father packed up the car neatly with our few belongings. My elder siblings, Sophaline and Makkara, took the Greyhound. We set out for the Central Valley, eager to be around other immigrant families who looked more like us and who, we hoped, would be more welcoming and accepting.

In Stockton, my father had difficulty finding a job that would make use of his hard-earned credentials. His teaching certificates and diplomas from Cambodia, which he had lost during the Khmer Rouge regime, and his fluency in French and Khmer did not matter here. For a short time, he and my mother worked as seasonal farm laborers, picking onions and cucumbers. My mother traveled to Oregon for a week with my sister Kunthear to pick strawberries. They came back with bags of frozen strawberries sprinkled with sugar but not much else. My father wanted to find work that would support our family and that also felt meaningful to him, so he attended the community college in Stockton to acquire an associate’s degree.

Meanwhile, he pushed us to study and work hard so that we could have what he felt he could not have: មុខ-មាត់ (moukh-meat). In Khmer, the words មុខ-មាត់ (moukh-meat) literally translate to “a face and a mouth,” “the ability to be seen and heard,” or “recognition and acceptance”—all of which were stripped from my father during the Khmer Rouge regime and were difficult to regain when he came here to the United States. Though he had been shamed and humiliated, he hoped that with education and privilege others would not មើលងាយ (meulngeay, look down on us).

Our struggle for recognition and acceptance led many of us, including my father, to adopt American names. My youngest brother, David Michael, was born in the United States, so he was given an American name. The rest of us were “naturalized” as American citizens. Makkara became Alexander. Phalkun, who was constantly taunted in school—the kids called her Falcon and Pumpkin—named herself Jacqueline. Sihakmony called himself Jonathan. My father, Sok Sann, which means “peace and tranquility” in Khmer, changed his name to Peter. The name Peter is derived from the Greek word petra, meaning “rock.” Floating in an ocean of uncertainty, perhaps my father felt he needed to be a strong and steady rock for us and for himself. To be tranquil and at peace was not enough.

Sophaline, Kunthear, and I were the only ones who did not change our names, though Kunthear added Margaret as a middle name, and I added Elizabeth, inspired by the English history, biographies, literature, and fairy tales I had read as a child, which taught me early on who belonged to the most privileged class.

My mother also did not change her name, Vann Theth, which means “a nocturnally fragrant flower.” She was adamant about keeping her Khmer name. She also never learned how to speak English. She told me that my father was often angry with her for not learning. “Aren’t you afraid your future American sons-in-law will មើលងាយ (meulngeay) you?” he asked. My mother could see how my father was suffering out there in the world with his “broken” English, and she didn’t want to be part of that. In her home and within her own realm, she was loved and respected, and that was all that mattered to her. She found daily comfort in cooking and caring for us, holding us close, and reminding us that she loved us. I realize now that if my mother spoke English, I might not be able to speak Khmer today. With the traditional foods she prepared for us and offered at the altar of our ancestors, and with the Khmer language she spoke at home, my mother was our lifeline, the umbilical cord to our homeland and to our true, unique selves.

My father expressed his love in different ways. He wanted more for us than he could ever have. Like a drill sergeant, he hammered in the importance of education and fitting in to this new American social fabric—be smart and educated enough to be acknowledged, but don’t stir things up so much that you’re noticed. My father distanced us from the Cambodian community in Stockton, although every week he would go out and drink with his Cambodian buddies. He bought a huge American flag, which he displayed with pride in front of the house, making sure that our Sikh, Vietnamese, Mexican, and white neighbors could see that we were good Americans. Although we didn’t have money, we learned to dress as if we had money, to buy a brand-new car even though we couldn’t afford it, to be book smart, and to speak with an “educated” white accent. We learned to make friends with white people, to look up to them as role models and leaders, and to work hard to gain their trust and respect.

At Thanksgiving—my father’s favorite American holiday—during the bountiful meal my mother cooked for us, my father would raise his glass (paying special attention to his daughters, who he believed needed more reminding than the boys) and declare in his heavily accented English: “Say no to the boyfriend. Say no to the sex. Say no to the drugs. Say yes to education!” He truly believed that if we could become part of the educated elite, no one could harm us as he had been harmed that fateful day in Houston.

Nearly every day after school, my father dropped us off at the Margaret Troke Library in Stockton and picked us up again right before it closed at nine o’clock in the evening. On Saturdays, my parents left us at the Cesar Chavez Central Library while they shopped at the flea market downtown. All the librarians knew us well. Some told my parents the library was not a day care. Some, like Bonnie Lew, became dear friends of our family. No matter how often we went to the library, I always came home with stacks of books, which I read on the toilet, at the bus stop, on the playground while other kids were playing, and at night in bed until my head began to nod, resisting sleep. My parents would smile at each other in the doorway and turn off the light, proud of their little girl who was always reading. They were completely oblivious to the trashy Danielle Steele novels I was hoarding beneath the covers—stories that showed me for the first time what it feels like to touch, kiss, and make passionate love. The books not only were my teachers but also became my friends and my escape from a place where I never felt I belonged.

We fled a genocide in Cambodia only to enter into another genocide of our ancestry, our identity, and the core being of who we are.

From fourth to sixth grade, I was placed in a Gifted and Talented Education program (GATE) for students who excelled in school. This was my first experience with the competitive American school system. There were white, Asian, and a few Hispanic students in my class, but no Black students, even though the school was predominantly Black and Hispanic. This trend, called “tracking,” continued into middle school and high school, where honors classes separated the “gifted” from the “normal” students. The gifted and honors students received more time and attention from teachers and were assigned guidance counselors, which offered more opportunities to excel in school. The “ungifted” students were labeled as difficult, challenging, and troublesome. While gang members from the Crips and the Bloods fired guns outside, we were discussing Richard Wright’s Black Boy and Native Son in our high school English honors class.

At school, I was always the first to raise my hand, unaware of other students around me who might have had something to say but needed more time to think or reflect. I would stay up late into the night working on school projects, because I enjoyed learning and the creative challenge. Yet the more I excelled and the more I was favored by my teachers, the more distant I felt from my peers. Each award or honor I received meant another child did not receive the same reward, further alienating them from me and me from them.

At the time, I didn’t question my privilege at school, nor the lack of privilege others might have had to endure to make my privilege possible. I accepted this norm and even embraced it, always trying to do better and be better. Even the history we learned in school legitimized this privilege. We learned about the white conquerors and their visionary quests in the New World. We never learned about all the bodies they infected and killed with “guns, germs, and steel.” We learned about the white settlers who escaped persecution to come to a land of freedom. We never learned that their freedom was founded on the massacre and persecution of people who lived on this land for thousands of years before they did. We learned about the economic ingenuity of the white founding fathers. And although we learned about slavery, we never learned that this economy was built on the backs of Black people brought to this land as slaves. We learned about the gold rush that drove thousands of white men to the West and about the Chinese people who helped them build the railroads that would serve to connect this great and expanding country. We never learned about the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which barred Chinese people—who comprised nearly a quarter of California’s wage laborers at the time—from entering the country. We also never learned that old-growth redwood forests once covered close to two million acres of the northern California coast and that the people who were stewards of this land revered and regarded these redwoods as sacred. In the history that was taught to me, the white conquerors were the explorers, and the white settlers were the freedom seekers, the founding fathers, and the pioneers. All other Black and brown people were footnotes: either exterminated, exploited, or assimilated. And if assimilation was not possible, they were excluded, demonized, or ignored, stripped of their មុខ-មាត់ (moukh-meat), their “face and mouth,” so they could not be seen or heard. I learned that those who conquer others are rewarded, those who rise above others are heroes, and those who are conquered, exploited, or exterminated deserve what is coming to them. I also learned that contrary to Reem Sav See’s wise words, the clarion call for many of these white settlers was, “Everything belongs to me; yet I belong to nothing.” This was the land to which my family immigrated.

It was not until I went to college at Yale that the tables turned for me and I learned how underprivileged my public education experience was, which made me critical of my elite university experience. Many students at Yale attended prep schools, majored in Latin, Greek, or the classics, and minored in music, theater, and visual arts. They came from legacy families; they even had the privilege and foresight to take a gap year to explore the world and reflect on what they really wanted to study. They were tapped into secret societies and played ultimate frisbee. In class, they spoke with such precision and confidence that they didn’t need to raise their hands. I cowered in their presence, oftentimes unable to utter a single word. What if I say something wrong? What if I make a fool of myself? These were the members of the educated and privileged class my father was preparing us all our lives to face. This was the educated and privileged class he wanted so much for us to belong to. Each time I spoke, l felt like I was being tested the same way my father was tested before we came to the United States; and I struggled, the same way he struggled to be validated every day of his life. My lack of privilege in college humbled me and forced me to question the roots and history of this system, and I learned that what happened to my father and my family was not unique. Every single person who has lived on or come to this land before us and has been excluded, demonized, ignored, or stripped of their មុខ- មាត់ (moukh-meat) is our ancestor too. Their trauma is our trauma.

Before the Khmer Rouge regime, life was different for my father. After he and my mother were married and had two children, they moved away from their families in Prey Veng Province to seek a new life together in Pailin. They settled in town near the central outdoor market. Hot-pink bougainvillea and nodding sunflowers lined the garden in front of the house. My father worked as a schoolteacher, a grade school principal, a nurse, and a gemologist. At that time, Pailin was covered with precious gemstones. My father brought home bags filled with raw rubies and sapphires, rough and unpolished. My mother lit candles and incense and placed the gems beneath each of the four corners of the សសរ (sasor, pillars of our house) to protect us from harm and evil spirits. For my parents, the gemstones were not signifiers of wealth but stones of protection.

My mother described my father in those days as being so gentle, loving, and creative. He organized the house, arranged the furniture, and hung paintings on the walls. When my mother gave birth, he took care of all the chores, not permitting her to lift a finger for at least two months. When they went to the cinema, my father straddled my sister Sophaline around his neck and held my brother Makkara’s hand. My mother only had to carry her purse. When Makkara was a baby, he peed in my father’s rice bowl. My father never scolded him. He just rinsed the rice with water and ate it. That’s how much your father loved his children, my mother told me. My parents never worried about food, money, or their health. They took care of the community, and they took care of each other, so there was not much more to care about.

My father was only sixty years old when he passed away, seventeen years after we arrived in the United States and only a few months before I graduated from college—a moment I knew would have made him feel honored, after all of the sacrifices he made for us. He died of liver cancer and severe cirrhosis of the liver. He also died from pain and heartache for a homeland he could never return to and the disappointment of a dreamland where he would never be accepted.

While most Yale graduates were competing for investment banking jobs, I decided to return to Cambodia to understand the country my father had left behind and the history that haunted and destroyed him. I wanted to understand myself and why I felt so uncomfortable being part of a competitive system; I’d seen how it encouraged me to devalue myself and others in the process. I returned to Cambodia to learn about my family before we were uprooted and torn apart. During the next twenty years, what I learned from the families I lived with in Cambodia, including Reem Sav See and her family in Areng Valley, is that there is a way of living with the land that is much more nourishing and in harmony with the Earth than the way we are living here. Being with Reem Sav See reminded me of my mother: the love and care she gave us through food and the respect and honor she gave our ancestors as she prayed daily at the altar. For my mother, even during the Khmer Rouge regime, there was no such thing as scarcity; food and love were always plentiful, and there was always enough to go around.

This was the way of living that my father lost when he came to this country and became blinded by his hope of a better life for us, with មុខ-មាត់ (moukh-meat), where others would not មើលងាយ (meulngeay) us. He had been humiliated, his face and voice silenced by a white man and a baseball bat. Unable to be who he was, my father fought to become something he was not, and he encouraged us to do the same—to work hard to become white and privileged—because he had learned that to be brown, to be poor, and to speak with a Cambodian accent was a disgrace.

Just as it was for my father, the struggle to fit in was more challenging for my brothers than it was for the women in my family. It was easier for us to blend in: our brown bodies were considered exotic and beautiful, our intelligence safe and nonthreatening, because we smiled often and always knew our place. For the boys, their dark brown bodies were seen as dangerous, completely foreign, and unplaceable.

My younger brother, Jonathan, refused to blend in. He fidgeted during family photos, made faces, and acted out the way any young boy would. My father did not like this. He knew there would be trouble if Jonathan could not fall in line. My father could not appreciate Jonathan’s brilliance, his rebellious spirit, or how similar they were: he himself had moved far away from his family’s village to forge his own future. My father disciplined my brother, hoping he could beat into him the sense he had beaten into himself. These beatings caused Jonathan to rebel even more. Although he excelled in school at first, surpassing me in the high school state debate tournament when I was a senior and he was only a freshman, Jonathan refused to study and become the obedient child my father wanted him to be. Drinking, smoking, and hanging out with friends were more fun and spoke to the angst he felt inside—the angst we all felt, but which only Jonathan, at the time, was honest enough to express. Less than a decade after he passed away, my father’s fears were realized: Jonathan was convicted of a crime he did not mean to commit—he was with the wrong person, in the wrong place, at the wrong time. If he hadn’t been a US citizen, Jonathan would’ve been deported to Cambodia like thousands of other young Cambodian men who’ve been pushed into tough situations and consequently joined gangs out of a sense of feeling lost.

For many years I wondered why I felt so lost. I had everything my father could have wanted for his children—education, honor, and respect from my peers and my community. I realized that in the process of acquiring all of this, I had lost my មុខ-មាត់ (moukh-meat), not as my father or society defines it, but as I define it for myself: to have a face that I recognize is a reflection of the beauty I see around me, and to have a voice that expresses my own unique inner wisdom—not what I’ve been taught or conditioned to express, but what I uniquely feel in my heart.

I learned to speak my voice from observing the elder women in Areng Valley who unapologetically fight at the front lines for their land, who aren’t afraid to laugh and lay bare their breasts, smoke, and tell crass jokes about their husbands. They don’t care what other people say or think about them. They only care about their land and this gift they will leave behind for their children, grandchildren, and all the children who will be born long after they are gone. They understand that legacy means dignity, not wealth. Integrity means love and community, not power. They also understand that their មុខ-មាត់ (moukh-meat) is a reflection of the diverse land and forests that they belong to.

For years I couldn’t understand my mother’s obsession with Cambodian jewelry, silk, and scarves. Every time I traveled to Cambodia, she would ask me to bring back jewelry or silk and handwoven scarves, along with twenty pounds of dried and roasted fish. I always did so reluctantly, reminding my mother of how busy I was, filming and working. I didn’t have time to shop for these things. When I brought the gifts home, my mother would carefully place the bundles of fish in the freezer, each week removing only a few pieces to cook and savor with a bowl of steamed jasmine rice. In this way, the fish would last for nearly a year, until I could make my way back to Cambodia again. She would add the silk and scarves to the pile she had amassed in her closet and store the gems in her jewelry box. “I’m saving all this for you and your sisters,” she said. “One day when I pass, all this silk and all these jewels will be yours too.”

When my parents lived in Pailin, my mother would light candles and incense and place raw gemstones beneath the សសរ (sasor) of our home to protect us from harm and evil spirits. When we had to flee our home, my mother sewed precious gems and gold necklaces into the seams of her pants. During our escape from one refugee camp to another, my father had to conceal the gems and gold coins in the crevices of his body to keep us safe against bandits. The jewels were our protection and our hope for a new beginning.

These gems and gold coins were not the only protection our family carried with us on our journey. When the Khmer Rouge came to power in 1975, two years before I was born, my family had to flee their home in Pailin with only the barest essentials—clothing, food, rice, and medicine, which they piled onto a cart that my father towed with his Honda motorcycle—joining throngs of families who were also forced to evacuate from their homes. They had to walk twelve kilometers before they were able to take shelter for the night. My mother cooked rice with sausage and salted fish. Sophaline and Makkara, who were only nine and seven at the time, asked my father if they could return home. My father’s heart stung with pain, swelled, and nearly burst like a balloon. “កូន (kaun, my children),” he said, “there is no chance that we will return home. We don’t know what place to call home or even where we are going. Please sleep and save your energy so that we can continue our journey tomorrow.”

Early the next morning, as they prepared to continue their journey, a man approached my parents and asked them if they had any medicine. His youngest child had diarrhea and had been vomiting for two days. The man had tried to buy medicine, but no one would sell him any. They told him money means nothing now. Gold is everything. My mother glanced at my father with softness in her eyes, and they both knew what they had to do. My mother comforted the man. She told him not to worry and that my father would go with him to see his child. My father went with the man and found his son sleeping on a mat, his arms and legs completely still. He took his temperature with a thermometer and gave him a shot. He then gave the man some extra medicine to give to his son. The man asked how much money he owed my father. “Nothing,” said my father. “We must help each other during these hard times.” They each bowed their heads, their palms folded together, touching their hearts. The man and his wife expressed a million thanks, vowing that they would never forget my father’s good deed.

When we arrived safely to the United States, my mother unraveled the stitches from her pants and strung a golden string of sapphires around her neck, one of the few remaining jewels we have left to remind us of our homeland. She wears them tucked beneath her blouse or proudly on her chest; I have never seen my mother without them.

Only a few years before his death, my father finally found work that honored the jewels he had brought with him from his homeland: his love for people and his commitment to his community. He worked as a counselor for the Refugee Resource Center of San Joaquin County, assisting Asian refugees with family reunification, crisis intervention, and filling out applications. He also volunteered as a counselor, providing support and guidance for young Cambodian men interned at the California Youth Authority. I had always seen him as a loving, caring father. But this was the first time I had seen him whole, as a proud member of his community, his face and voice finally accepted and recognized. Many of the young men he counseled and supported came to his funeral, helping carry his coffin on their shoulders.

I wonder what would’ve happened that day our car was attacked if my father had remembered the ancestral jewels he carried in his heart and the jewels my mother wore on her breast to protect us from harm. What might have happened if he hadn’t remained silent but had confronted the man who smashed his car with a baseball bat? What might have happened if he had spoken to my mother? If he had spoken to us and told us his story? If he had told us what happened and why it happened and how wrong and unjust the white man’s behavior was? I wonder what might have happened if he had told us that we would never give in to the powers that seek to deface and silence us. If my father could have remembered that he was protected by the jewels and wisdom of his ancestors, maybe he wouldn’t have changed his name to something foreign, a rock seeking strength and stability. Maybe he would’ve kept the peace and tranquility of his birth name and the strength of his face and voice—he would’ve remained whole, and all of us would’ve been whole too.

The jewels were our protection and our hope for a new beginning.

Recently, my sister Kunthear expressed to me her fear that her memory of our father was fading. She was afraid that with time she would forget him and that he and his memory would disappear forever. As we were speaking, we reflected on a backpacking trip we took together two summers ago in the Sierra Nevada, where David and I embark on our pilgrimages each year. We had plans to complete the 211-mile John Muir Trail in four weeks (we had completed 29 miles of the trail a few years before that). It was to be a journey of a lifetime, celebrating Kunthear’s fiftieth birthday.

As we started our hike, Kunthear fell sick, unable to acclimate to the rising elevation. Just before flying out to California from Texas, she had loaded the car and driven her daughter, Apsaline, to Austin to start her very first year of college. For weeks, she had cooked and packed the freezer with jars of soup and food for her husband and thirteen-year-old son, Edward, to eat while she was away. Her friends and community rallied behind her, ready to take Edward to and from school and offer her the support she needed to complete her hike. Kunthear did all she could to prepare for the trip, but she was not prepared herself.

We walked slowly, taking it one step at a time, breathing deeply and resting often. We completed only a couple of miles the first day. On our second night, we set up camp near a stream lined with purple, broad-leaved lupines and golden arrowleaf groundsel. Butterflies fluttered around us as we took turns bathing in the stream. I filtered water for us to drink, set up our tent and sleeping mats, and prepared a bone broth soup of vegetables and glass noodles for dinner.

I asked Kunthear if she wanted to go back. I suggested that we could rest for a few days, get acclimated, and then get back on the trail again. “Let’s keep going,” she insisted. “This will pass.”

The following day, we climbed even higher and Kunthear’s energy did not improve. Every ten minutes we stopped to rest. Kunthear kept apologizing for her slowness. I laughed and reminded her there was no rush to get anywhere. We were already in the mountains.

When we finally reached the next campsite, six miles from our first exit point at Duck Pass, I again set up the tent so Kunthear could rest, filtered water for us to drink, and made another bone broth soup, which I urged Kunthear to drink despite her fading appetite. The sun shone bright and golden in the late-summer sky. Kunthear wore a red, blue, and yellow plaid krama wrapped around her shoulders, her slick black hair pulled back in a ponytail. Her eyes glistening with tears, she thanked me for taking care of her. “I’m always taking care of others,” she said. “I rarely have time to take care of myself. As the elder sister, I should be caring for you. Yet here you are, carrying all the food, setting up the tent, cooking our food, and even making coffee and breakfast for me in the morning. Even your movements and gestures remind me of Paa (our father). This was what he did for us when we fled our home. Quietly and humbly, he took care of us and made sure we were always healthy and safe. This is what you are doing for me now.”

I wanted to tell Kunthear that as long as we were alive and we honored our father with our words and actions, both he and his memory would remain alive too.

These are the ancestral jewels that my father forgot, that we carried in our hearts all the way from our homeland, and that, my mother reminds me, are still with us today.

In Khmer, the word for “resolve” is ដោះស្រាយ (daohsray): ដោះ (doah) means “to remove”; ស្រាយ (sray) means “to untie, disentangle, or unravel.” To honor my dear father’s memory, to bring him back to life again, and to feel whole and at home, I only have to remember to do what my beloved mother had done: ស្រាយ (sray) the stitches I’ve sewn around my heart and ដោះ (doah) the jewels to reveal their splendor, reflecting the beauty and stillness of my heart, the peace and tranquility of my father’s birth name, and the wisdom of our ancestral stories.

Pickled Limes

During the Khmer Rouge regime in Cambodia, Kalyanee Mam’s mother nourished and sustained her family with umami soups, chicken rice, and fried noodles. Years later, as Kalyanee cooks for her husband and mother-in-law who have fallen ill during the pandemic, she reflects on food as a conduit for healing and love and shares her mother’s recipe for Pickled Lime Soup.