Wendell Berry is a farmer, teacher, and the author of more than forty works of fiction, nonfiction, and poetry. He is the recipient of numerous awards and honors, including a Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship, a National Institute of Arts and Letters award for writing, the American Academy of Arts and Letters Jean Stein Award, the Lyndhurst Prize, and the Aitken-Taylor Award for Modern American Poetry from the Sewanee Review. He lives and works with his wife, Tanya Berry, on their farm in Port Royal, Kentucky.

Alice Waters is a chef, author, food activist, and founder and owner of Chez Panisse Restaurant in Berkeley, California. She is the founder of the Edible Schoolyard Project and co-created the Yale Sustainable Food Project. Her honors include an American Academy of Arts and Sciences fellowship; Harvard Medical School’s Global Environmental Citizen Award; and induction into the French Legion of Honor. And in 2015, she was awarded the National Humanities Medal by President Obama. Alice is the author of sixteen books, including her critically acclaimed memoir, Coming to My Senses: The Making of a Counterculture Cook.

Studio Airport, founded by Bram Broerse and Maurits Wouters, is an interdisciplinary design studio that ventures out into the cultural ether to forage for anomalies, creating work that spans art, culture, science, and ecology. In addition to Emergence Magazine, their creative partners include the Design Museum, See All This Art Magazine, Slowness, Normal Phenomena of Life, and Sapiens Magazine. They serve as master tutors at the Design Academy Eindhoven and were recognized as European Agency of the Year 2024 by the EDA.

When I first read Wendell Berry’s essay The Pleasures of Eating nearly thirty years ago, it electrified me. Wendell launches the essay with that brilliant line of his: “Eating is an agricultural act.” That statement reverberated deeply and articulated for me a fundamental truth about how I want to live my life.

At the time this essay was published, I had been running Chez Panisse for about eighteen years. I had started the restaurant as a little place to feed my friends in the counterculture—a place where we could gather around the table, eat delicious food, and discuss the politics of the time. We didn’t set out with food activism in mind. Instead, it was our pursuit of taste that brought us to the doorsteps of the small, local organic farmers. As we developed relationships with those producers—men and women who were growing flavorful heritage crops and farming in traditional ways that protected the land—we realized how dependent we were upon them, and they upon us. Over the years, that local network of organic suppliers came to define the food and philosophy at Chez Panisse. We realized how much our lives were enriched by the values they brought into the restaurant. We were experiencing a dawning awareness that our everyday food choices were agricultural—were, indeed, political—and that we could either choose to strengthen the global industrial food system or choose to participate in an entirely different local, rural economy.

In these three intervening decades, I have come to fully understand the astonishing, uncanny prescience of Wendell Berry’s vision. Here, he outlines the entire dysfunction of our current industrial food system: namely, how the food industry divorces us from the land, and in doing so, pulls the wool over our eyes about the wrongdoings taking place within that system every day. Wendell shows us how we are all victims of fast food culture, made passive and dependent by the multinational industrial food conglomerates. We have all been indoctrinated by the values of this fast food culture, told that cooking is drudgery; that food should look and taste the same all year round, wherever we are in the world, no matter what the season; that time is money, and speed should be cherished above all else; that our choices, food-related or otherwise, have no consequences.

These are, of course, a series of falsehoods, and Wendell exposes them all with piercing clarity. These falsehoods resonate even more today in the face of imminent climate chaos. But Wendell’s is also a message of hope: here he guides us with seven practical, succinctly presented suggestions for how we can lead our lives more humanely. These proposals are simple. They make sense. They connect us to the land and to the traditions that have sustained us since the beginning of civilization. And they are pleasurable.

Pleasure, to Wendell, is essential. This essay is a warning, but it is also a reminder of the joy that comes when you live in tune with the natural world. In this manner, too, Wendell could see into the future. He saw the potential for a powerful counterforce to fast food culture, one based around those earthbound values that knit us together as human beings on this planet.

Wendell Berry was more than just prescient. He wrote in such a lucid, lyrical way that we have as much to learn from him now as we did then—more perhaps, now that we need so desperately to hear his hopeful message. Thirty years later, I believe we are ready for Wendell.

Many times, after I have finished a lecture on the decline of American farming and rural life, someone in the audience has asked, “What can city people do?”

“Eat responsibly,” I have usually answered. Of course, I have tried to explain what I meant by that, but afterwards I have invariably felt that there was more to be said than I had been able to say. Now I would like to attempt a better explanation.

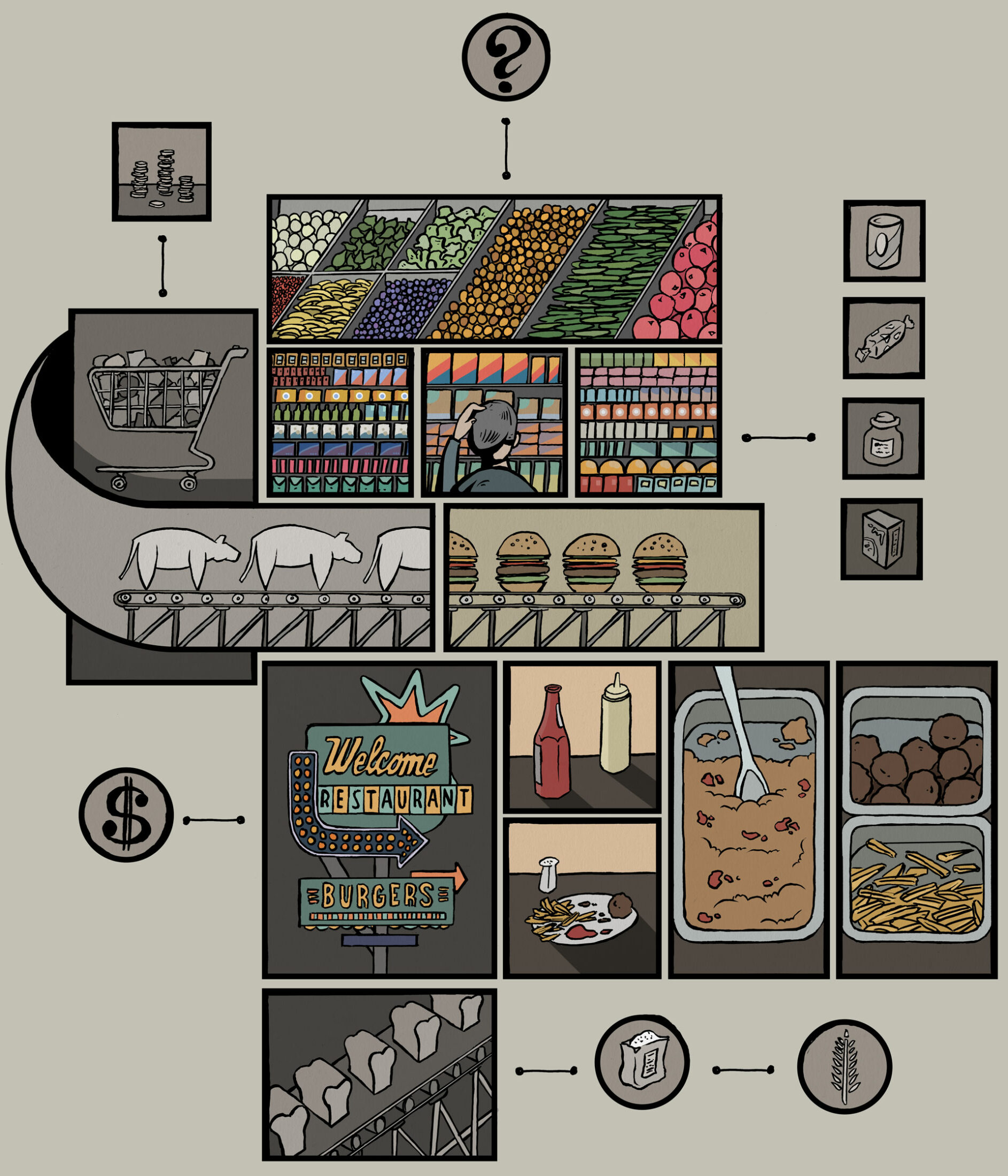

I begin with the proposition that eating is an agricultural act. Eating ends the annual drama of the food economy that begins with planting and birth. Most eaters, however, are no longer aware that this is true. They think of food as an agricultural product, perhaps, but they do not think of themselves as “consumers.” If they think beyond that, they recognize that they are passive consumers. They buy what they want—or what they have been persuaded to want—within the limits of what they can get. They pay, mostly without protest, what they are charged. And they mostly ignore certain critical questions about the quality and the cost of what they are sold: How fresh is it? How pure or clean is it, how free of dangerous chemicals? How far was it transported, and what did transportation add to the cost? How much did manufacturing or packaging or advertising add to the cost? When the food product has been manufactured or “processed” or “precooked,” how has that affected its quality or price or nutritional value?

Most urban shoppers would tell you that food is produced on farms. But most of them do not know what farms, or what kinds of farms, or where the farms are, or what knowledge or skills are involved in farming. They apparently have little doubt that farms will continue to produce, but they do not know how or over what obstacles. For them, then, food is pretty much an abstract idea—something they do not know or imagine—until it appears on the grocery shelf or on the table.

The specialization of production induces specialization of consumption. Patrons of the entertainment industry, for example, entertain themselves less and less and have become more and more passively dependent on commercial suppliers. This is certainly true also of patrons of the food industry, who have tended more and more to be mere consumers—passive, uncritical, and dependent. Indeed, this sort of consumption may be said to be one of the chief goals of industrial production. The food industrialists have by now persuaded millions of consumers to prefer food that is already prepared. They will grow, deliver, and cook your food for you and (just like your mother) beg you to eat it. That they do not yet offer to insert it, prechewed, into your mouth is only because they have found no profitable way to do so. We may rest assured that they would be glad to find such a way. The ideal industrial food consumer would be strapped to a table with a tube running from the food factory directly into his or her stomach.

Perhaps I exaggerate, but not by much. The industrial eater is, in fact, one who does not know that eating is an agricultural act, who no longer knows or imagines the connections between eating and the land, and who is therefore necessarily passive and uncritical—in short, a victim. When food, in the minds of eaters, is no longer associated with farming and with the land, then the eaters are suffering a kind of cultural amnesia that is misleading and dangerous. The current version of the “dream home” of the future involves “effortless” shopping from a list of available goods on a television monitor and heating precooked food by remote control. Of course, this implies and depends on a perfect ignorance of the history of the food that is consumed. It requires that the citizenry should give up their hereditary and sensible aversion to buying a pig in a poke. It wishes to make the selling of pigs in pokes an honorable and glamorous activity. The dreamer in this dream home will perforce know nothing about the kind or quality of this food, or where it came from, or how it was produced and prepared, or what ingredients, additives, and residues it contains—unless, that is, the dreamer undertakes a close and constant study of the food industry, in which case he or she might as well wake up and play an active and responsible part in the economy of food.

There is, then, a politics of food that, like any politics, involves our freedom. We still (sometimes) remember that we cannot be free if our minds and voices are controlled by someone else. But we have neglected to understand that we cannot be free if our food and its sources are controlled by someone else. The condition of the passive consumer of food is not a democratic condition. One reason to eat responsibly is to live free.

But if there is a food politics, there are also a food esthetics and a food ethics, neither of which is dissociated from politics. Like industrial sex, industrial eating has become a degraded, poor, and paltry thing. Our kitchens and other eating places more and more resemble filling stations, as our homes more and more resemble motels. “Life is not very interesting,” we seem to have decided. “Let its satisfactions be minimal, perfunctory, and fast.” We hurry through our meals to go to work and hurry through our work in order to “recreate” ourselves in the evenings and on weekends and vacations. And then we hurry, with the greatest possible speed and noise and violence, through our recreation—for what? To eat the billionth hamburger at some fast-food joint hellbent on increasing the “quality” of our life? And all this is carried out in a remarkable obliviousness to the causes and effects, the possibilities and the purposes, of the life of the body in this world.

One will find this obliviousness represented in virgin purity in the advertisements of the food industry, in which food wears as much makeup as the actors. If one gained one’s whole knowledge of food from these advertisements (as some presumably do), one would not know that the various edibles were ever living creatures, or that they all come from the soil, or that they were produced by work. The passive American consumer, sitting down to a meal of pre-prepared or fast food, confronts a platter covered with inert, anonymous substances that have been processed, dyed, breaded, sauced, gravied, ground, pulped, strained, blended, prettified, and sanitized beyond resemblance to any part of any creature that ever lived. The products of nature and agriculture have been made, to all appearances, the products of industry. Both eater and eaten are thus in exile from biological reality. And the result is a kind of solitude, unprecedented in human experience, in which the eater may think of eating as, first, a purely commercial transaction between him and a supplier and then as a purely appetitive transaction between him and his food.

Our kitchens and other eating places more and more resemble filling stations, as our homes more and more resemble motels.

And this peculiar specialization of the act of eating is, again, of obvious benefit to the food industry, which has good reasons to obscure the connection between food and farming. It would not do for the consumer to know that the hamburger she is eating came from a steer who spent much of his life standing deep in his own excrement in a feedlot, helping to pollute the local streams, or that the calf that yielded the veal cutlet on her plate spent its life in a box in which it did not have room to turn around. And, though her sympathy for the slaw might be less tender, she should not be encouraged to meditate on the hygienic and biological implications of mile-square fields of cabbage, for vegetables grown in huge monocultures are dependent on toxic chemicals—just as animals in close confinement are dependent on antibiotics and other drugs.

The consumer, that is to say, must be kept from discovering that, in the food industry—as in any other industry—the overriding concerns are not quality and health, but volume and price. For decades now the entire industrial food economy, from the large farms and feedlots to the chains of supermarkets and fastfood restaurants, has been obsessed with volume. It has relentlessly increased scale in order to increase volume in order (presumably) to reduce costs. But as scale increases, diversity declines; as diversity declines, so does health; as health declines, the dependence on drugs and chemicals necessarily increases. As capital replaces labor, it does so by substituting machines, drugs, and chemicals for human workers and for the natural health and fertility of the soil. The food is produced by any means or any shortcut that will increase profits. And the business of the cosmeticians of advertising is to persuade the consumer that food so produced is good, tasty, healthful, and a guarantee of marital fidelity and long life.

It is possible, then, to be liberated from the husbandry and wifery of the old household food economy. But one can be thus liberated only by entering a trap (unless one sees ignorance and helplessness as the signs of privilege, as many people apparently do). The trap is the ideal of industrialism: a walled city surrounded by valves that let merchandise in but no consciousness out. How does one escape this trap? Only voluntarily, the same way that one went in: by restoring one’s consciousness of what is involved in eating, by reclaiming responsibility for one’s own part in the food economy. One might begin with the illuminating principle of Sir Albert Howard’s The Soil and Health, that we should understand “the whole problem of health in soil, plant, animal, and man as one great subject.” Eaters, that is, must understand that eating takes place inescapably in the world, that it is inescapably an agricultural act, and that how we eat determines, to a considerable extent, how the world is used. This is a simple way of describing a relationship that is inexpressibly complex. To eat responsibly is to understand and enact, so far as one can, this complex relationship. What can one do? Here is a list, probably not definitive:

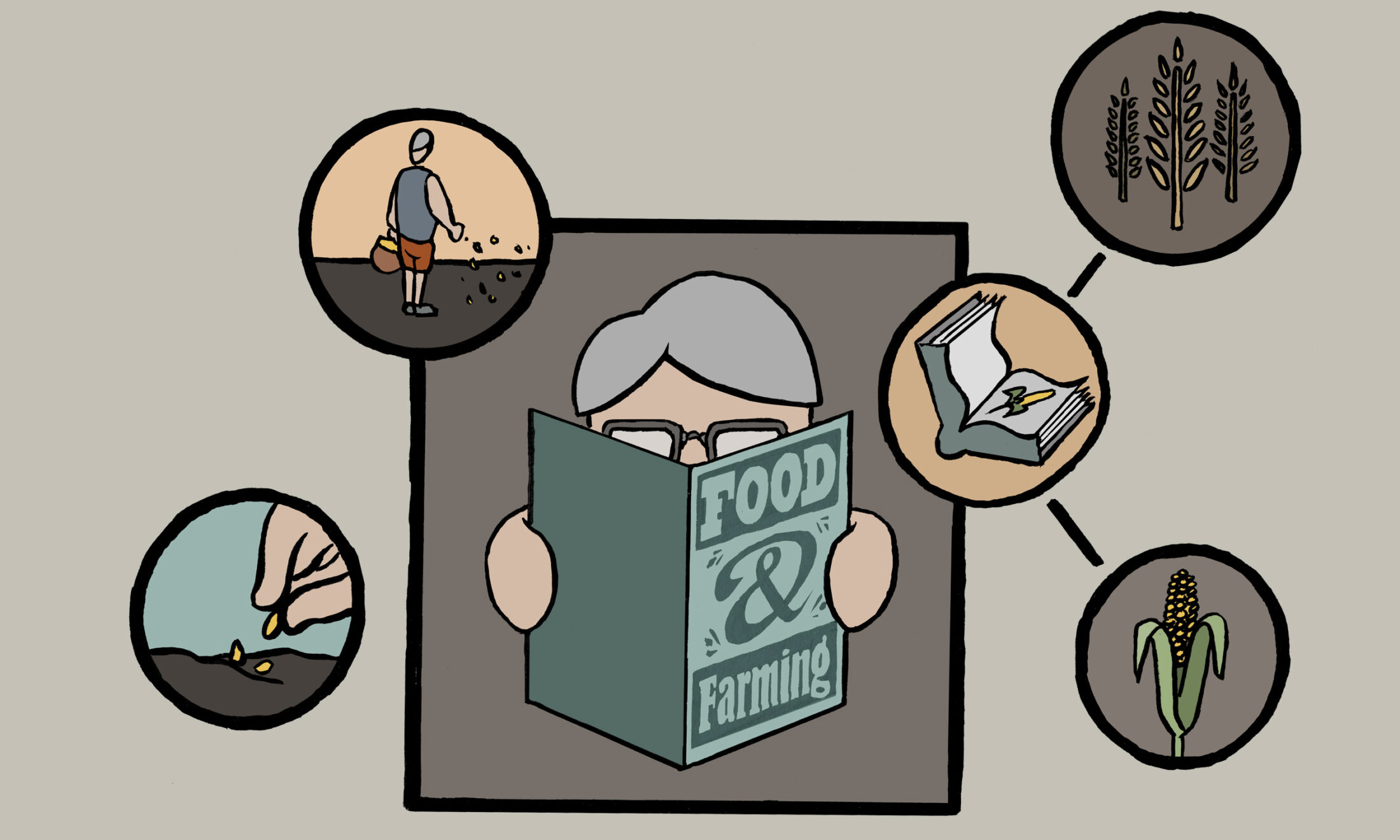

1. Participate in food production to the extent that you can. If you have a yard or even just a porch box or a pot in a sunny window, grow something to eat in it. Make a little compost of your kitchen scraps and use it for fertilizer. Only by growing some food for yourself can you become acquainted with the beautiful energy cycle that revolves from soil to seed to flower to fruit to food to offal to decay, and around again. You will be fully responsible for any food that you grow for yourself, and you will know all about it. You will appreciate it fully, having known it all its life.

2. Prepare your own food. This means reviving in your own mind and life the arts of kitchen and household. This should enable you to eat more cheaply, and it will give you a measure of “quality control”: You will have some reliable knowledge of what has been added to the food you eat.

3. Learn the origins of the food you buy, and buy the food that is produced closest to your home. The idea that every locality should be, as much as possible, the source of its own food makes several kinds of sense. The locally produced food supply is the most secure, the freshest, and the easiest for local consumers to know about and to influence.

4. Whenever possible, deal directly with a local farmer, gardener, or orchardist. All the reasons listed for the previous suggestion apply here. In addition, by such dealing you eliminate the whole pack of merchants, transporters, processors, packagers, and advertisers who thrive at the expense of both producers and consumers.

5. Learn, in self-defense, as much as you can of the economy and technology of industrial food production. What is added to food that is not food, and what do you pay for these additions?

6. Learn what is involved in the best farming and gardening.

7. Learn as much as you can, by direct observation and experience if possible, of the life histories of the food species.

The last suggestion seems particularly important to me. Many people are now as much estranged from the lives of domestic plants and animals (except for flowers and dogs and cats) as they are from the lives of the wild ones. This is regrettable, for these domestic creatures are in diverse ways attractive; there is much pleasure in knowing them. And farming, animal husbandry, horticulture, and gardening, at their best, are complex and comely arts; there is much pleasure in knowing them, too.

It follows that there is great displeasure in knowing about a food economy that degrades and abuses those arts and those plants and animals and the soil from which they come. For anyone who does know something of the modern history of food, eating away from home can be a chore. My own inclination is to eat seafood instead of red meat or poultry when I am traveling. Though I am by no means a vegetarian, I dislike the thought that some animal has been made miserable in order to feed me. If I am going to eat meat, I want it to be from an animal that has lived a pleasant, uncrowded life outdoors, on bountiful pasture, with good water nearby and trees for shade. And I am getting almost as fussy about food plants. I like to eat vegetables and fruits that I know have lived happily and healthily in good soil, not the products of the huge, bechemicaled factory-fields that I have seen, for example, in the Central Valley of California. The industrial farm is said to have been patterned on the factory production line. In practice, it looks more like a concentration camp.

The pleasure of eating should be an extensive pleasure, not that of the mere gourmet. People who know the garden in which their vegetables have grown and know that the garden is healthy will remember the beauty of the growing plants, perhaps in the dewy first light of morning when gardens are at their best. Such a memory involves itself with the food and is one of the pleasures of eating. The knowledge of the good health of the garden relieves and frees and comforts the eater. The same goes for eating meat. The thought of the good pasture and of the calf contentedly grazing flavors the steak. Some, I know, will think it blood-thirsty or worse to eat a fellow creature you have known all its life. On the contrary, I think it means that you eat with understanding and with gratitude. A significant part of the pleasure of eating is one’s accurate consciousness of the lives and the world from which food comes. The pleasure of eating, then, may be the best available standard of our health. And this pleasure, I think, is pretty fully available to the urban consumer who will make the necessary effort.

I mentioned earlier the politics, esthetics, and ethics of food. But to speak of the pleasure of eating is to go beyond those categories. Eating with the fullest pleasure—pleasure, that is, that does not depend on ignorance—is perhaps the profoundest enactment of our connection with the world. In this pleasure we experience and celebrate our dependence and our gratitude, for we are living from mystery, from creatures we did not make and powers we cannot comprehend. When I think of the meaning of food, I always remember these lines by the poet William Carlos Williams, which seem to me merely honest:

There is nothing to eat,

seek it where you will,

but of the body of the Lord.

The blessed plants

and the sea, yield it

to the imagination

intact.