The Myth of Progress

Paul Kingsnorth is a writer living in rural Ireland. In 2009, he created and launched Dark Mountain Project, a writers’ and artists’ movement designed to question the stories our culture is telling itself in a time of ecological and social unraveling. Paul has won various prizes for his poetry, including the 2012 Wenlock Prize. His first novel, The Wake, was longlisted for the Man Booker Prize and won the Gordon Burn Prize and the Bookseller Book of the Year Award. Paul’s second novel, Beast, was shortlisted for the Encore Award for the best second novel. The third, and final, installment in this trilogy, Alexandria, is forthcoming. Paul published his first collection of essays, Confessions of a Recovering Environmentalist, in 2017, and his most recent nonfiction book, Savage Gods, was released in 2019.

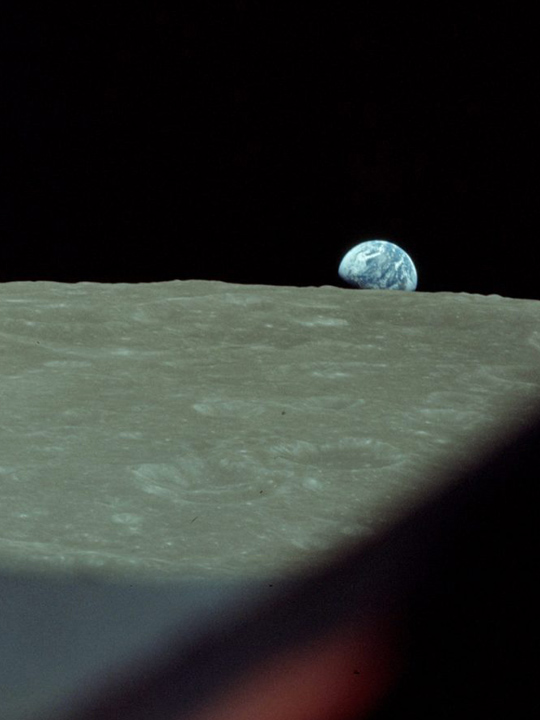

Emmanuel Vaughan-Lee is an author, Emmy- and Peabody Award–nominated filmmaker, and a Sufi teacher. He has directed more than twenty documentary films, including Taste of the Land, The Last Ice Age, Aloha Āina, The Nightingale’s Song, Earthrise, Sanctuaries of Silence, and Elemental, among others. His films have been screened at New York Film Festival, Tribeca Film Festival, SXSW, and Hot Docs, exhibited at the Smithsonian Museum and London’s Barbican, and featured on PBS POV, National Geographic, The New Yorker, and The New York Times Op-Docs. His new book, Remembering Earth: A Spiritual Ecology, is forthcoming from Shambhala in summer 2026. He is the founder, podcast host, and executive editor of Emergence Magazine.

In this interview, writer Paul Kingsnorth discusses some of the central themes explored in his work. The conversation centers on the “myth of progress,” the failure of technology to deliver the “good life,” and how both have led us into the environmental crisis. He describes how old myths offer a way to be with the uncertainty embedded in our time, and how we can listen for new stories.

Transcript

Emergence MagazineI wanted to start with a more general question to help frame our discussion today, and that’s really the question of: What role do stories have in helping us to understand the environmental crisis we are now living through?

Paul KingsnorthI mean, in one sense, everything we do is a story, everything we think is a story, and everything we tell ourself about the world is a story. Every culture has its own stories, which is why cultures end up being so different from each other. We tell ourselves a story about, for example, our relationship with the rest of nature. So, if you were to talk about modern Western society, you could say that the story that it tells itself about its relationship with the rest of life on Earth is that there is something out there called “nature” that is rather different from humans. We’re either above it or we’re separate from it, and we have a relationship with it really based on extraction.

One of any number of indigenous cultures around the world would tell a different relationship. A lot of those cultures don’t have a word for nature because they don’t see it as anything separate from themselves, which is true of most premodern cultures.

It’s my feeling that we’re living in an age of global crisis. It’s more than a feeling—much of that is measurable. We know about climate change, we know about extinction, and we know about deforestation and all of the other horrors of what industrial society is doing to the Earth.

It’s my suspicion that much of that has to do with having told ourselves the wrong stories about the relationship that humanity has with the rest of the Earth. If you are a society that tells itself a story that human beings are separate from the rest of nature—that human beings are really the center point and the centerpiece of the planet, that life is primarily measurable through economics and science—then you end up with a relationship with the rest of the Earth and with the rest of life where you see both largely as material goods to be exploited.

That’s a story, and it’s a damaging story. I think that the story of our separation from nature and our superiority to it is probably at the heart of the ecological crisis that we’re unleashing on the world. The question that interests me at that point is: what stories could we tell instead that would give us a healthier relationship with the natural world?

EMYou talk about a “crisis of stories.” Could you talk a little bit more about that and what that means?

PKWhen we look at the ecological crisis, we tend to look at it through the lens of economics or politics or science or culture. So, we might say that the problem is that we’re using the wrong technologies, that we’re burning fossil fuels and putting gases up into the atmosphere, and that we need a different kind of energy source. We might say that we have political systems that don’t work, as they are not allowing nations to cooperate with each other in a way that can protect the planet properly.

We might say that it’s an economic problem. We might say, for example, that because we don’t put a price on nature, that means that we don’t value it properly, and that we could use economics to value the natural world properly. While all of that may be true, and all of those points are maybe worth making, I think that the deeper problem is a problem of relationship, which is maybe another way of talking about stories.

We have in our culture a particular relationship with the rest of life which, I think, is based on the notion that we’re separate from it, and that we can either protect it or exploit it. That it’s really something “out there” that is different from us. It’s not something that we are equal to. That to me is a kind of human chauvinism, and that’s an incorrect story. You can see it’s an incorrect story by looking at the damage we’re doing externally. You can also look inside yourself and ask yourself if that story seems satisfying to you on a spiritual level, which I don’t think it does to a lot of people.

So, what story would you tell instead? How would you tell a story in which we were not separate from the rest of life, but connected to it? How could you tell that story in a way that has meaning for people? Can you do that in a society like this in which we are so disconnected in everyday life? I don’t know. But that’s the big question for me.

EMIf you had to name the most powerful story or myth that tells this story of disconnection from nature, what would it be and what name would you give it?

PKProbably the central story of our culture—which I think has replaced a lot of the religious stories that used to be at the heart of our culture—is the story of progress.

What we say is: it is possible, through human ingenuity, to create a utopia. We have a story that tells us that human beings started as ignorant savages and are moving through a series of progressive steps, in which, at every point, they get cleverer, they get richer, they get smarter, they develop technologies which allow them to live longer, they learn more. Eventually, that ends with us probably leaving the planet and colonizing the stars, or living forever, or downloading our brains onto silicon chips. It’s a kind of technological rapture that sees time in a linear fashion rather than in a cyclical fashion.

It sees an endless series of steps, every one of which improves things in the material sense from the one before. I don’t think it’s historically true. Actually, what happens is that things tend to rise and fall in cycles. But it has an enormously powerful grip on us, and it informs everything from our view of the past, which we increasingly believe was a savage place in which our lack of technology and science drove us to a sort of misery and poverty, to our view of the future, in which we assume that more technology and more scientific focus and more centralization will take us to a kind of paradise.

And so we have this story that we believe in which everything continues to get better every generation, and our job is to keep that process going. I think once you believe that, then you are stuck in a very linear narrative. You are unable to see, you are unable to learn much from the past on your own, and you are probably unable to learn much from the mistakes of the present as well.

EMWould you say then that that story—if you believe it, or if you’re striving to be a part of it—then gives you permission to abandon stories and myths that you may have believed to be true, or that are a part of your cultural conditioning, or that you are a character in?

PKOne of the dangerous things about the story of progress is that we don’t think it’s a story. We think it’s the truth. We think it’s real, rather than that it’s simply an interpretation of the world which we have chosen to believe. I think that all of us believe it in some way because it’s how we were brought up. It’s just what we think is happening. In every generation, things are getting better and better through the use of technology and science. And so, if you can improve people’s lives generation upon generation, then they can start to believe that that’s an endless process that will go on forever.

But we’re only managing to do that by stripping away the life support systems of the planet. And so, at some stage, you start to reach a reckoning. If we start getting two or three or even four degrees of climate change over the next century or so, then the material benefits, the short-term benefits that people are getting at the moment from that process, start to look pretty hollow. That’s what’s starting to happen now. We can see the ecological limits being hit, and we can see all sorts of pain and difficulty emerging from that. But it hasn’t hit enough people in the wealthy world for that to be a process that really makes people think differently about this notion of progress and modernity.

EMWould you say the myth is unraveling? This story is unraveling?

PKThe thing about progress, as a notion, is that if things don’t continue to get better for most people generation upon generation, then it’s not possible to believe [in progress] anymore. That’s starting to happen. If things get really considerably worse ecologically, then it will happen considerably faster. Then it will be something impossible to believe. At that point you’ve got a lot of chaos coming down the line, because when your stories fracture, the things that you believe to be true stop being true.

EMPeople are increasingly realizing, through personal challenges in their own lives, that they can’t have the same lifestyle as their parents, that they can’t buy a house and so forth. The social and political upheaval that’s starting to become apparent in the West reveals that there is a challenge with this story we have. How would you go from removing yourself from that story to being part of a new story, which, as you were saying earlier, is more about living in relationship with the Earth, and is connected to an older story? It seems like a big leap in some ways to make.

PKI think it is a big leap. I don’t think it’s a leap that you can consciously make. I don’t think we are in a situation where we can sit down and say, “Right, we need a new story and a new way of seeing.” People’s worldviews and their stories and their myths develop out of their circumstances. That’s true of any culture. From the smallest tribe to the biggest civilization, people develop a story that fits with their practical experience. While we’re all still wealthy and sitting around having middle class lifestyles, the story of progress makes perfect sense. It will only change when those things fall away.

When we hit a wall and it’s impossible to believe that this is working anymore, when things are getting considerably worse for most people, then we’ll start thinking about the world differently. New things will emerge from that, but that’s a long process. It’s not something that can be consciously constructed. I think we are making a mistake if we think we can sit down and draw up some sort of monomyth or new way of seeing that everyone is supposed to buy into. We will believe what appears to be true. For some people in the world today, it appears to be true that things continually progress in a sort of upward direction. There are a lot of other people for whom it doesn’t look true.

EMWhat made you shift from thinking that you could create new stories, tell new stories, and share new stories that would shift people’s perspectives, to this idea you have now in which these perspectives will shift in their own time in response to people’s circumstances?

PKWell, I think I can still do that in a way. It’s what I do when I write, although I don’t necessarily do it consciously. But the act of writing an essay, or the act of writing a novel, or the act of telling any kind of story are very small ways of telling different stories and challenging things. I think actually that that’s what the work is—people doing things at really quite a small level—at a personal level—doing their small work.

I think that what I used to believe (arrogantly, probably)—that we could work together to create some grand new story for humanity—was just foolish. But that doesn’t mean that lots and lots of small stories don’t come together to form something bigger, which I think is probably how it always works. If enough people are questioning the way the world works and the values we have and the stories we tell ourselves, then what they will start to do instead will start to add up to something. This is really what we have been trying to do with the Dark Mountain Project for nearly ten years.

EMYou spoke earlier about old stories that have been around in different forms and representing different cultures for as long as we’ve been around. Could you talk a bit about the role of these older stories in helping us understand the crisis of our current situation, and what role they play as we, in all the different ways we are telling them, honor or take into account that knowledge that was present before?

PKIt seems to me that a lot of the stories that we need are there already, and that what we’re looking at here is not a process of creating a new story that we somehow all have to live by, but rather of paying attention to older ones that we’ve forgot. That might mean stories from indigenous cultures, it may mean fairy tales, it may mean old myths, it may mean stories in some of the old religious books. But a lot of the stories that we need, in terms of giving us an indication of how we can live well with the rest of the world, are probably out there already.

One of the problems in our culture is that we don’t quite know how to hear these stories anymore. We tend to want to rationally analyze and imagine that we can intellectually grasp and understand every aspect of something that we hear in order for it to make sense, but that’s not necessarily the case. A lot of the older stories and the myths work on you on a level that isn’t necessarily rationally measurable, but you can still see what’s going on. They come from a time when people were still living in a broadly oral culture and were hearing stories in a communal setting. These stories gave them a relationship between people and places and landscape.

[Stories] start to work on you, and they change the way that you see the world—that’s been my experience of them—in a way that no amount of argument and no number of rational cases ever could. You start to see the kind of symbolism and the meaning beneath a lot of everyday stuff.

EMThis theme of relationship that you mentioned is almost a replacement for the word “story.” Could you talk a bit more about how relationship was present in these older stories between people and landscapes and places, and how that can offer an example of how to lead us into these tellings of newer stories?

PKIn European fairy tales, very often the landscape is alive with magic and strangeness. There’s another world that is in a constant relationship with the material world we live in. Most of that stuff in those fairy tales is treated very casually. An old woman will walk out of a tree and deliver a message to you, and there will be fairies and demons in the woods. People can talk to animals, and animals can talk to them. This is not necessarily meant to be taken literally, in the sense that you will walk into the woods and a deer will talk to you or offer you a secret. But there’s this constant notion of an endless exchange in language between humans and the rest of nature, which you also find in many indigenous cultures, too: that you are just in a conversation with the rest of nature. Whereas, in our society, we’re not in a conversation with the rest of nature. We have forgotten how to hear it. We don’t talk to it: it’s a resource. We either protect it or we exploit it. We don’t really feel threatened by it; we don’t feel we have to give much to it.

If you close that door between the human world and the other world—the world of humans and the world of the forest—if you put a great fence between the village and the forest, then you’re in for some big trouble. Stories that can break that wall down or can open that door again—take us out into that strange, almost supernatural exchange between people and the rest of life—are stories that we need now. They are stories I have ended up writing in my fiction as well, not even necessarily intentionally. I find in the fiction that I write, the places, the landscape, and the natural world are as much characters as the humans. Often [these characters] have a voice and they’re in an exchange with [the humans], which isn’t always necessarily a pleasant exchange or a benevolent one.

But you’re in a conversation with the landscape, in a conversation with the natural world and with other things. We just don’t really know how to do that anymore. I think it’s something we could be relearning, clumsily. I think it’s what we need to fumble towards. How do we get that conversation going again? For me, that’s the big question now.

EMTalk to me more about relearning. That doesn’t seem to be a very Western concept. As we think about responding to problems or creating something new or dealing with challenges, we’re usually focused on: solution, execution, an approach that feels very different from relearning.

PKSure, well, I mean, what if there’s something we have forgotten? What if we’ve forgotten how to speak to and to listen to other things that live? I think it’s a question of shutting our mouths for a while and being a bit humble and going outside and listening and learning again.

I think that one of the things we are really good at as a society is identifying a problem and proposing a solution to the problem, then going off and putting that [solution] into place. That’s been our kind of special genius as modern humans, which is why we’ve got so much technology and so much power.

But we’re very, very bad at listening to what everything else has to say. We don’t really believe any of it is alive. I think that learning from old stories, listening to them, listening to storytellers, paying attention to indigenous ways of seeing, and just going out and listening and paying attention to things does start to subtly change your worldview. It certainly happened to me; and I couldn’t point to any enormous instantaneous change that has happened to me, but certainly over the last ten years, this notion—that I don’t really know everything and that I’ve got a lot to learn, rather than a lot to teach, and that there is a conversation I don’t know how to have, that I’d like to learn how to have—has been a constant for me, and it’s changed me subtly.

There’s still a lot I’d like to do and a lot I’d like to learn, a lot I’d like to know. I think that’s increasingly such an important task: just to learn how to listen, to relearn what we’ve forgotten. I don’t think there is any easy sort of ABC curriculum for it. There’s a lot of work you can do.

EMThis notion of listening is actually very challenging for people to understand. Most people having a conversation are thinking about what they are going to say next rather than listening to what the person or the landscape or the non-human presence is offering. What does it mean to listen and how can we listen?

PKI think that stories come from people connected to landscapes. Again, the old fairy tales and myths work because they are told by people who really have paid attention to the forest and the creatures in it. I just think it’s very hard for us to listen. Last year I spent four days sitting in a wood with no food on a wilderness vigil—a rite of passage, if you like, a vision quest—in which you choose a spot to sit in, you make your little circle of fifty feet around you, and you don’t move out of that for four days. You don’t eat anything, you just drink. You just sit there and pay attention and see what happens, not necessarily with the expectation that anything spectacular will happen. It’s very hard work, actually, to get yourself out of your head and your own expectations—to not get impatient, to want to do something, to want to walk off and do something productive. I think that’s the society that we’ve found ourselves in. It’s very hard to sit still and pay attention. But after about three days of being forced to do that, you do realize that it is possible, and you end up just sitting there and listening.

It’s just a fascinating process. You notice the sounds of the forest in a way that you wouldn’t have noticed them before. You notice the touch of the wind on your skin. You can hear music that you didn’t think you could hear before. Your relationship with the land has deepened in a way that you can’t quite put your finger on.

You start to see, even if you just do that for a few days, how somebody who’d grown up in a culture that just lived in a forest and relied on it for their lives would have a completely different relationship with that landscape. Totally different. Like I say, I think that process of relearning how to listen is so important. We’re either going to do that successfully, or that’s gonna be the end of this particular cultural experiment that humans are on. It’s just not sustainable in any sense to be a culture that just takes, and just passes by and just walks through and doesn’t listen.

You can’t create stories unless you’re listening to something. You can’t create stories that have any meaning unless the rest of nature can speak to you in some way, or unless you can hear what it’s got to say. Unless there’s an exchange, you’re just humans talking to other humans about humans in a human world. That’s a broken world, actually. If it’s just got people in it, if it’s got nothing else, if there’s no exchange with anything else outside our bubble, then we haven’t got any story to tell that’s real.

EMI’m very much in agreement with you. At the same time, the majority of people live in cities, and the majority of the people who are currently living in rural parts of the world are most likely going to be moving to cities in the next twenty years. How does that play into the story of learning how to listen, when the reality is that most people are not going to be in places where they will be able to listen, because their physical environment does not even allow listening?

PKWell, that’s part of the crisis, isn’t it—which is only going to get worse before it gets better. All I can say to that is that those people who are in a position to pay attention, to listen, to try and write or create new ways of seeing, have a responsibility to do that. They probably also have a responsibility to protect what remains of older societies of indigenous cultures, who are still endlessly suffering colonization, land theft, extinction, and annihilation. I do increasingly think that a lot of the really important work around the world is going on in indigenous cultures, and they continue to be pushed out and destroyed by settled cultures and city-based cultures. If we can’t protect them and the stories that they carry and the knowledge that they have, then we’re in some trouble.

I always come back to the same answer, which is that those of us who can do what we can should just do it without any expectation that it’s going to lead to a quick world-changing solution, because I don’t think it is. It’s more a sense that—those of us who can, building refuges, protecting what we can protect, telling the stories we can tell, trying to look for truth—if that’s what we’re doing—and hoping that that can be passed down generations as things go on. It’s a long process. I think Gary Snyder said something like “we’re in a two-thousand-year or maybe even a five-thousand-year process of trying to live well on the Earth.”

I don’t think that this is something that we are going to turn around in a generation or two. I think it’s just slow work, so we will just do what we can do.

EMIt seems, at least from my reading of the trajectory of your work over the last decade or so, that you’ve been exploring more concepts that could be described as spiritual or sacred in relationship to place and people. Those ideas of things being spiritual are often dismissed by mainstream culture, yet they seem to have an important role to play in the telling of these new stories, or just in listening to what was present in the older stories from that perspective.

PKIncreasingly, it seems to me that the kind of spiritual void, if you want to use that word, at the heart of our culture is the essential thing. If you don’t hold anything sacred at all, if you don’t believe as a society or as an individual that there is anything greater than you, whatever that thing is, then everything is about you. If you have a society that doesn’t believe anything is greater than itself, then it becomes—what we’ve become I think—narcissistic and materialistic, really almost a society of what Buddhists would call “hungry ghosts,” wandering around and eating the world.

I’ve written a little bit about this. I was always very struck with the meaning of the word “holy.” It is an Old English word—the original word is hālig, which also meant whole, as in not separated, not divided. If you see the Earth as whole, you have a very different relationship to it than if you see the Earth as a collection of separate parts which you can use and manipulate. I think that we as a society don’t hold anything sacred anymore, and, as you say, even using words like sacred or spiritual will invite derision in a lot of quarters. We’ve convinced ourselves that everything that matters can be measured.

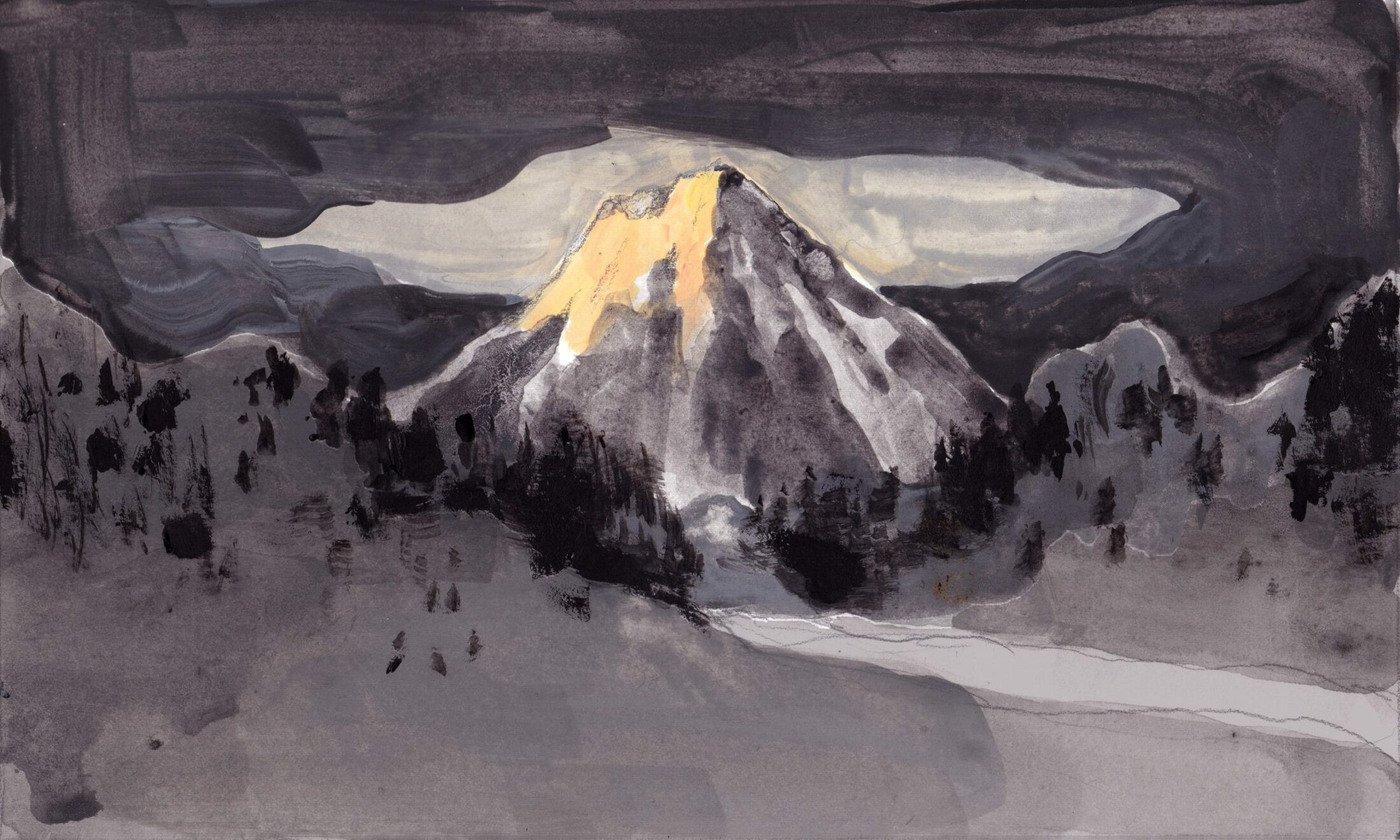

I think that’s the heart of the crisis that we have. The way that we react to a beautiful forest, or a sunset on a mountain, or a whale breaching in the ocean, the way that way we personally react to that is always hugely emotional. You know, you have a deep emotional connection to that, it stirs something in you. That’s not something that can be put into words very often. It’s very real, but because you can’t put it into words or measure it, we treat it as if it isn’t real. That old animal, emotional, spiritual connection to the natural world—we just pretend it isn’t there anymore, or that it’s just a kind of bit of fluff that doesn’t really matter, but it does. I think it’s the heart of things. If you don’t acknowledge that sense of specialness, holiness, otherness, wonder, and beauty in the natural world, then you haven’t got anything. You’ve lost one the most central parts of being human, and the stories you tell are always going to be empty.