Rampart House, 1920

Public domain

The Dissolution

Bathsheba Demuth is an environmental historian, specializing in the lands and seas of the Russian and North American Arctic. She is the author of Floating Coast: An Environmental History of the Bering Strait, which was named a Nature Top Ten Book of 2019, listed as a Best Book of 2019 by NPR, Nature, Kirkus Reviews, and Library Journal, and winner of the 2020 George Perkins Marsh Prize. Her other writings can be found in The American Historical Review and The New Yorker.

Environmental historian Bathsheba Demuth observes the spread of COVID-19 while researching the 1911 outbreak of smallpox among the Vuntut Gwitchin of the North Yukon and ponders waiting, isolation, and the dissolving partition between world and self.

These are my memories of the dissolution. You might also call it February 2020.

In February the sun would be just rising when I left for the 8:46 Fairbanks municipal bus. The light was palest pink at the horizon, lifting into azure where the moon hung. It was not possible to look at these colors and breathe fully. The poplar and aspen and spruce all wore shadow limbs of snow on each branch, their trunks thickened where the north wind had packed six-inch drifts up their sides. Every tree itself, but also a crystalline second self. It was cold in the old way, –20°F, –25°F, sometimes –30°F as I danced from foot to foot at the bus stop, listening to news broadcasts on my headphones. Any vulnerable margin of the body—the inside of my nostrils, lip corners, the tender skin rimming my eyes—tightened and chilled, caught between the warmth within and cold without.

The bus—a blast of warm air, hello from the burly driver—carried me toward the hilltop campus of the University of Alaska Fairbanks. The ticking blur of the news in my ears: The president had been impeached. Something about the Super Bowl halftime show. The Iowa caucuses: who won? The Nasdaq Composite Index gained 63.47 points. The Chinese city of Wuhan was on lockdown for a second week because of a novel coronavirus. The S&P 500 rose 5.66 points. Parasite won best picture at the Academy Awards. Antarctica reached a record 68 degrees. The Dow Jones Industrial Average gained 115.84 points. The world arrived in encapsulated narratives, politics divided from culture divided from health divided from the environment. Somewhere in every newscast was the economic report, gnomic incantations of rising, gaining, closing above, like proclamations of a vital sign.

Off the bus, I paused to look toward the slopes of the White Mountains, their blue-shadowed peaks lost in the glimmering dim of ice fog. Then the daily plunge into the library: industrial carpet, humming lights, students clustered over laptops. Down the flights of stairs to the basement home of the Alaska and Polar Regions Collections and Archives. At the threshold I ceded present for past and turned off the news.

The past waited on a cart arranged by the archivist: sometimes large rectangular boxes, sometimes smaller files or reels of microfilm that smelled vaguely like a darkroom. I was in the earliest days of learning to write about the Yukon River. At this stage, a book is not chapters or even sentences, but immersive incoherence in the raw stuff of the story. Some of that material was in this archive, a repository that like most was not indexed by theme or place, but where pieces of the larger whole were seeded across thousands of pages. One morning I might be reading miners’ letters from the Klondike in the 1890s and by afternoon would be bent over twentieth-century salmon fishing regulations. The process both permeated and ruptured: the lint of old paper under my nails, lungs cloggy with dust, the fleshy pads of my fingers split by papercuts, even tears, one afternoon, at the impossible slowness of deciphering two century-old longhand Russian letters. Trying to find some narrative line, a distinct theme, made my eyes blur. I imagined my brain overheating like a dog sprinting in August.

What made facing this thronging confusion possible was running. At 4 p.m. the archive closed, and I was free to loop and wind through the small wildlife refuge near where I lived, for as long as I could stay warm. The trails were packed snow and springy underfoot, twisting through open marshes and stands of birch, some bent double under the weight of the miniature drifts on their branches. I did not run with headphones. There was just the whisper of snow blown gently from the trees, the long, blue, gold-crested shadows of the afternoon sinking into twilight. These runs were as near to flying as I have ever come. And cold. By the time I turned for home, I could not feel the line where my limbs ended and the air began.

In my headphones, by late February: COVID-19 in South Korea. Super Tuesday was soon: who would win? Cases in Italy. Community spread in Washington State. How to wash your hands. The S&P 500 lost 0.4%, but the Nasdaq Composite gained 0.2%. The vital signs were unstable.

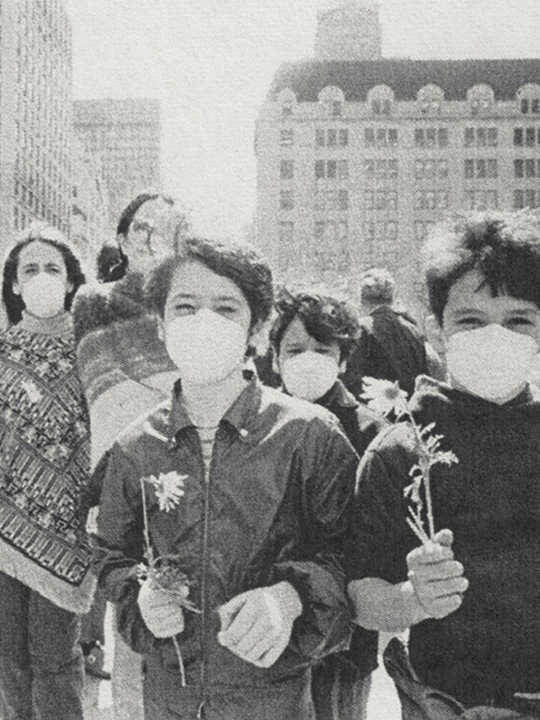

In the archive, time and place eddied and mixed. Sometimes I would catch something on the current: a name I’d seen in an earlier file, the third mention of an event. One morning—a morning when I heard COVID-19 compared to the 1918 influenza pandemic—my reading came to a known place. It was hiding in a bland-looking document, The Joint Report upon the Survey and Demarcation of the International Boundary Between the United States and Canada along the 141st Meridian—an account of the team that marked the border between the Yukon Territory in Canada and Alaska just over a century ago. Sixty-three pages in, the barge hauling the surveyor’s supplies “had managed to get one load as far as Rampart House.” I knew Rampart House. It was an abandoned trading post on a tributary of the Yukon River called the Porcupine. I had lived, two decades ago, about twenty-four bends upriver, in the Vuntut Gwitchin village of Old Crow.

The report described the work of hewing a border from the Arctic land: moving people by horses and boats, cutting sightlines into the black spruce forest, setting markers, calculating latitude and longitude. There were mentions of the weather and river ice. Then, very briefly in 1911: “a physician … discovered an Indian girl at Rampart House suffering from what he diagnosed as smallpox.” The boundary team sent word to the nearest town, Dawson City, which dispatched a Royal Northwest Mounted Police constable to establish quarantine. “The necessity of keeping the survey parties away from Rampart House complicated matters somewhat,” the report noted, “but fortunately not one member of the survey contracted the disease.”

My breath caught. I knew about this epidemic. In Old Crow, I’d heard stories about the fall and winter after the constable came, after a doctor ordered almost a hundred Gwitchin onto an island in the middle of the Porcupine. The police burned everything left on shore, the canvas tents where people had lived, their caches of dried meat and fish, the harnesses for their sled dogs and the sleds. On the island, people lived in a hastily-built infirmary. Almost half fell ill. One infant died. And one was born. Ellen Bruce, whom I passed some time with when she was ninety, took her first breaths on Hospital Island.