Michael W. Twitty is an African-American and Jewish writer, culinary historian, and educator. He is the author of The Cooking Gene, which won the 2018 James Beard Foundation Book Award for Book of the Year and was a finalist for The Kirkus Prize in nonfiction, the Art of Eating Prize, and a Barnes and Noble New Discoveries finalist in nonfiction. His blog Afroculinaria explores the culinary traditions of Africa, African America, and the African diaspora.

Stephen Crotts is an illustrator and painter based in South Carolina. He graduated from Winthrop University with a Bachelor of Fine Arts in Visual Communication Design in 2008. After graduating, he worked as an artist-in-residence in New Orleans, LA. He was a founding member of Friday Arts Project.

Recalling his mother’s New Year’s Day black-eyed peas recipe, Michael W. Twitty traces this legume back to the Middle Passage and its roots in Africa, recognizing it as a seed of Black resilience.

When my mother was still here in body, she made a small pot of black-eyed peas every New Year’s Day. The pot was so small, in fact, that it held the volume of only about two cups of cooked peas.

“I thought you loved black-eyed peas?” I asked her.

“I don’t love them; I don’t really even like them. I just eat them because of tradition.”

“That’s a lot for tradition.”

“How else am I supposed to get good luck and change?”

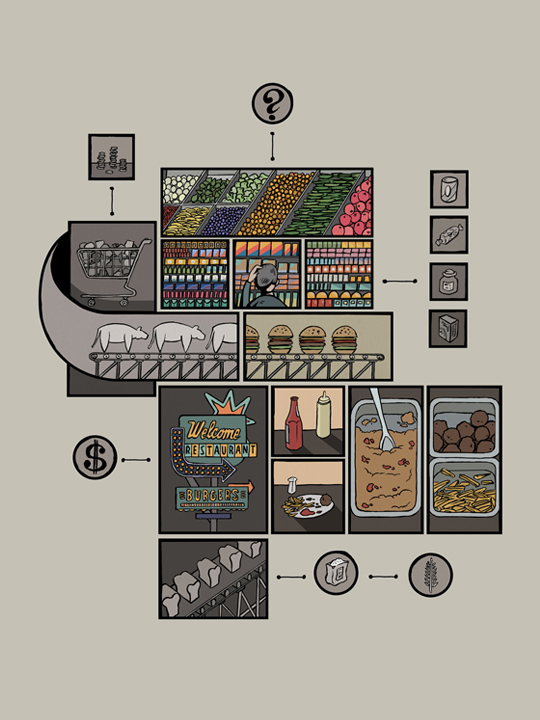

In the South, a mess of black-eyed peas is eaten alongside greens as a good-luck food at the start of the civil year. No book preaches this scripture. It is word of mouth, the process of the heart, a lived text. Both foods were endemic to West Africa and the gardens of enslaved people in the South; their story, no matter what, is bound to the racial caste system of early America.

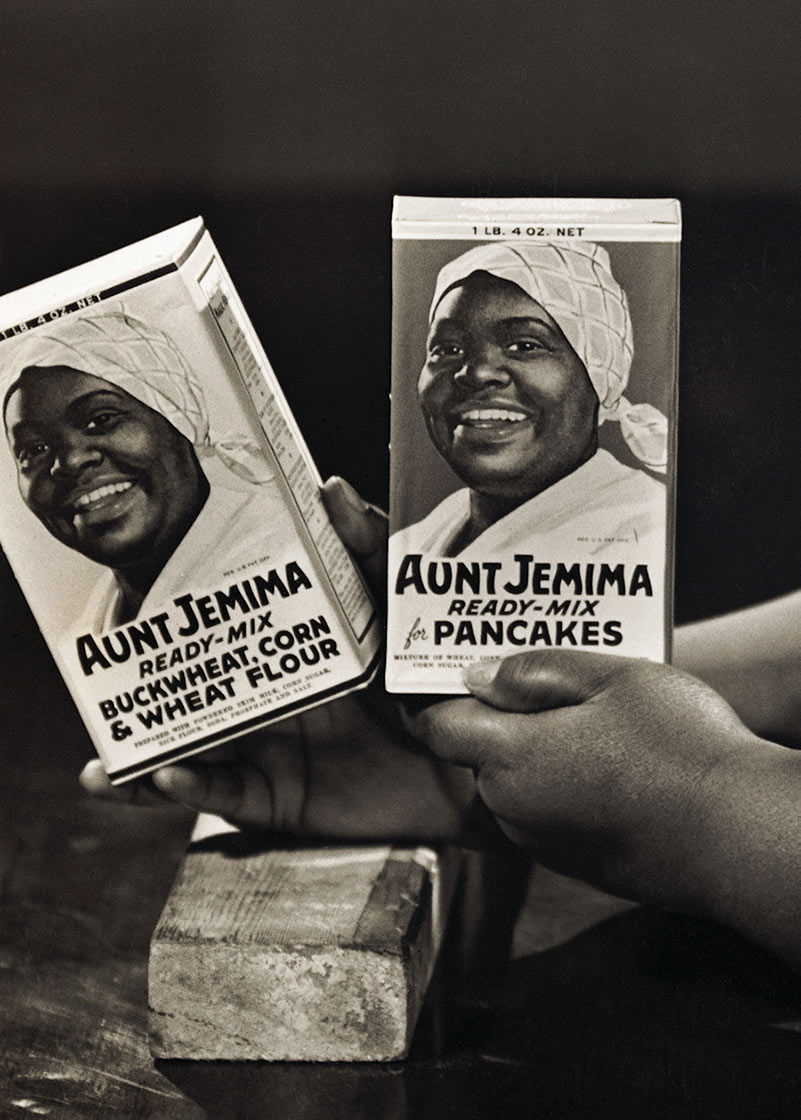

A recent photograph taken at a Southern museum attributed this tradition to white Civil War soldiers. Black-eyed peas were one of many varieties of field pea, also known as cowpeas, that crossed the Atlantic during the transatlantic slave trade. The museum caption, however, associated this Southern tradition with starving, gray-uniformed soldiers forced to consume livestock feed. Indeed, Robert E. Lee called the black-eyed pea “the only unfailing friend the Confederacy ever had.”

The caption had nothing to do with reality or fact. Not even a hint. It was part of another tradition of divorcing the Old South from its Black and African roots. This tradition left little room for me, a Black child, to know myself as an American and to understand my origins and the contributions of our Ancestors. The story of me and the black-eyed pea is how a single ingredient helped me do just that.

Vigna unguiculata (cowpea) is everywhere in the tropical world. The story of this long-podded, viny pea is in hundreds of thousands of families. It has nourished generations across the globe. From its botanical birthplace in sub-Saharan Africa to the Middle East and the Mediterranean, to India, Southeast Asia, Brazil, Mexico, the Caribbean, and the American South—the cowpea’s story is one that is borne by a seed.

Every time I see black-eyed peas, I flash back to one distinct moment in my childhood: seeing the peas soaking within a cool, bowl-bound sea. The clear water shows multitudes of wide, world-absorbing eyes going deep down to the bottom.

“They look like eyes staring back at me.” I am three; my head is resting on my hand, but lazily. My mouth is twisted, and my eyes are troubled. I am watched by my own prospective dinner. My mother and grandmother, famous for telling me that they have eyes in the backs of their heads, have adopted a new tactic: by way of these black-eyed peas, they are spying on me from the soaking bowl and, later, my plate. I am a boy child without free will.

Meat and bones are a matter of horror and delight to the young. Meat can be tasty. Bones are reminders that pieces of meat are not fruits or vegetables. They are our first memento mori, the first guarantees of the inescapable reality of death. Many of us prefer our meat cut from the bone, not just because young fingers fumble, but because we want a divorce from the life-and-death nature of food.

Into the pot went ham hocks and onion. The onion invited you like a trap. So did the smoky smell of the hock. It was years before I knew what made that smell possible. I refused to believe that umami perfume could come from the body part of a dead animal I could not identify.

I didn’t like black-eyed peas and I didn’t like soul food and I didn’t particularly like being Black. It was strange; I genuinely felt white people and the white world to be beyond exotic. They were alien. And yet they were the default. I had to answer to the silence in the world when it came to understanding my day-to-day experiences.

My family worked very hard to undermine the currents of anti-Blackness in my life. Black-eyed peas were not pizza or hamburgers.

I was an immigrant of circumstance. I was the first generation born outside of assumed second-class citizenship on paper. I wanted normality. I wanted to be universal and to be a real citizen of the world around me, not imprisoned by weird folkways I didn’t understand. I wanted fast food, wealth, an easy life, and all the benefits of whiteness I could not yet articulate.

My mother, in her time, shelled whole bags of field peas. Late summer, she and her sisters would get a shelled yield that equaled maybe a store’s bag and a half of seed. My maternal grandfather bought them from hawkers on the streets of Cincinnati. This was her heritage, one of many remnants of the Old South in a Great Migration life. My mother was the child of refugees from Alabama who missed the taste but not the laws and customs passed down from the days of their grandparents, born into the world of slavery.

My family worked very hard to undermine the currents of anti-Blackness in my life. Black-eyed peas were not pizza or hamburgers. They were earthy and alien. Pot after pot, I was drawn into story after story, starting with my mother on a Cincinnati stoop and on to her mother in a Birmingham kitchen, and before her a sharecropper’s shack, and before then the bottomlands of a rural Alabama plantation, and prior, a garden in Virginia or the Carolinas.

On the stroke of midnight every New Year’s, my grandmother handed me dried peas to put in everyone’s wallet or purse. My mother had so many purses, I used up half a bag on her alone. “I don’t have no money, so get them in there.” It was my job. I put a few black-eyed peas in my wallet. My grandmother told me as long as they were in my wallet, I’d keep money around me.

Africa was once remote in this narrative. Now it is not. Vigna unguiculata was born in the heart of West Africa long before the trade was a thought. Books told me this. Research told me that by the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, this seed was in North America. Oral tradition whispered on pages said that seeds were brought in the hair of our Ancestors during the Middle Passage. Everyone said it—from Philadelphia to Savannah to Port-au-Prince to Recife. The cowpea was at the center of yet another tradition: a transnational myth of resilience.

Nobody had seeds in their hair, really; the seeds were in their minds and symbolically in their hearts. We do know that seeds were brought on those ships. It was a particularly useful food. The seeds held up well. They were prolific and could be cooked into the “slabber sauce” served in buckets to my enslaved African ancestors. In Senegal I was told they were used to bulk up the men. Good luck, indeed.

Before we were exiled, they were fritters and puddings. They were wedding foods symbolic of goddesses of fertility. They were charitable food shared with the poor. They were a symbol of the unclosing eyes of the Creator and Ancestors. Our peas were tiny little texts, and we didn’t even know it.

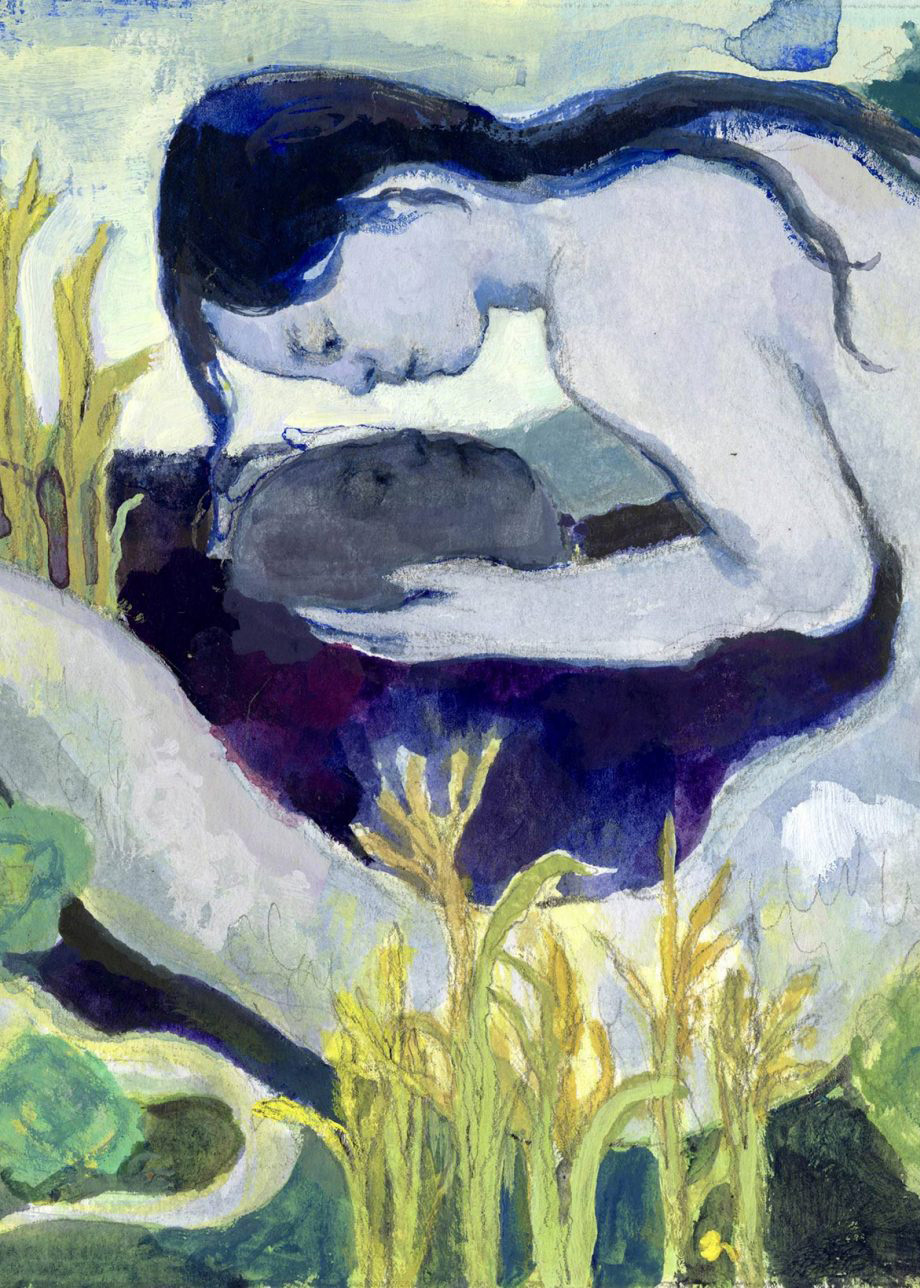

The search for their meaning has, in many ways, been a search for the missing pieces of myself. I went from reluctantly eating one pea at a time to growing my own just before my mother transitioned, and I learned to admire their luxuriant, deep-green vines; pretty white, yellow, and purple flowers; and ample pods. Then I had my first green peas. Then I made them into salads, made fritters, pickled their green pods, ate them with rice per my Carolina blood. I told stories about Oya and Mami Wata and Alabama.

My mother may not have liked black-eyed peas, but her love was undeniable, both for me and for the tradition. Each pot was a bit of our immortality going back millennia. Now this lineage is in my own recipe.

Black-Eyed Peas Soup

Serves 6-8

Ingredients

For the soup

· 2 tablespoons olive oil

· 1 medium red onion, chopped

· 2 garlic cloves, chopped

· 1 small shallot, chopped

· Kosher salt, ground coriander, kitchen pepper,* several pinches of each

· 1½ pounds collard greens, trimmed from the stalk and sliced into thin, very small strips

· 2 cups chopped fresh heirloom tomatoes, or 14-oz. can chopped plum tomatoes

· 2 teaspoons dried marjoram or oregano, or 2 sprigs of fresh marjoram and oregano

· 2 cups cooked black-eyed peas,** or 2 cans black-eyed peas

· 4 cups vegetable stock

(optional ingredients)

· more broth for the cooked black-eyed peas

· protein, such as pork, lamb, or duck bacon; ham hock; smoked turkey; or soy meat products

*For the kitchen pepper

· 2 teaspoons freshly ground black pepper

· 1 teaspoon ground white pepper

· 1 teaspoon red-pepper flakes

· 1 teaspoon ground mace

· 1 teaspoon ground Saigon cinnamon

· 1 teaspoon ground nutmeg

· 1 teaspoon ground allspice

· 1 teaspoon ground ginger

Preparation

**For cooked black-eyed peas

Sort through a 1-lb. bag of black-eyed peas. Look for any stones or “off” peas or stray objects. Soak overnight in cold water or in hot water for just over an hour and drain. In a large saucepan, add the peas and cover with low-sodium vegetable stock and bring to a boil, skimming frequently. Reduce the heat and simmer, covered, for 1¼ hours or until quite soft, occasionally stirring gently. For extra flavor and richness, you can add a protein to the bubbling pot—like pork, lamb, or duck bacon; ham hock; smoked turkey; or soy meat products.

For the soup

In a large Dutch oven, gently heat the olive oil and add the onion, garlic, and shallot. Cook until translucent and fragrant. Add a pinch of kosher salt, a pinch of ground coriander, and a pinch of kitchen pepper. Add the collards and cook for 4–5 minutes. Add the tomatoes and season again with a generous pinch of kosher salt and gentle pinches of coriander and kitchen pepper. Cook slowly until the tomatoes break down into a sauce, about 15 minutes. If using dried herbs, add them at this stage.

Add the peas and vegetable stock to the pot and simmer for 45 minutes. If using fresh herbs, add during this stage, but remember to remove sprigs when it’s time to serve. Add final pinches of kosher salt, coriander, and kitchen pepper.