Kalyanee Mam is a Cambodian-American filmmaker whose award-winning work is focused on art and advocacy. Her debut documentary feature, A River Changes Course, won the World Cinema Grand Jury Prize for Documentary at the 2013 Sundance Film Festival and the Golden Gate Award for Best Feature Documentary at the San Francisco International Film Festival. Her other works include the documentary shorts Lost World, Fight for Areng Valley, Between Earth & Sky, and Cries of Our Ancestors. She has also worked as a cinematographer and associate producer on the 2011 Oscar-winning documentary Inside Job. She is currently working on a new feature documentary, The Fire and the Bird’s Nest.

Adam Loften is an Emmy- and Peabody Award–nominated filmmaker and producer of virtual reality experiences and podcasts. His films include: Sanctuaries of Silence, The Atomic Tree, Counter Mapping, and Welcome to Canada. His work has been featured on PBS, National Geographic, The Atlantic, and The New York Times.

Ken Pelletier is an entrepreneur, technologist, photographer, musician, and documentary filmmaker focusing on environmental and social justice issues. He serves on the board of directors of the Chicago Media Project and Mother Jones Magazine.

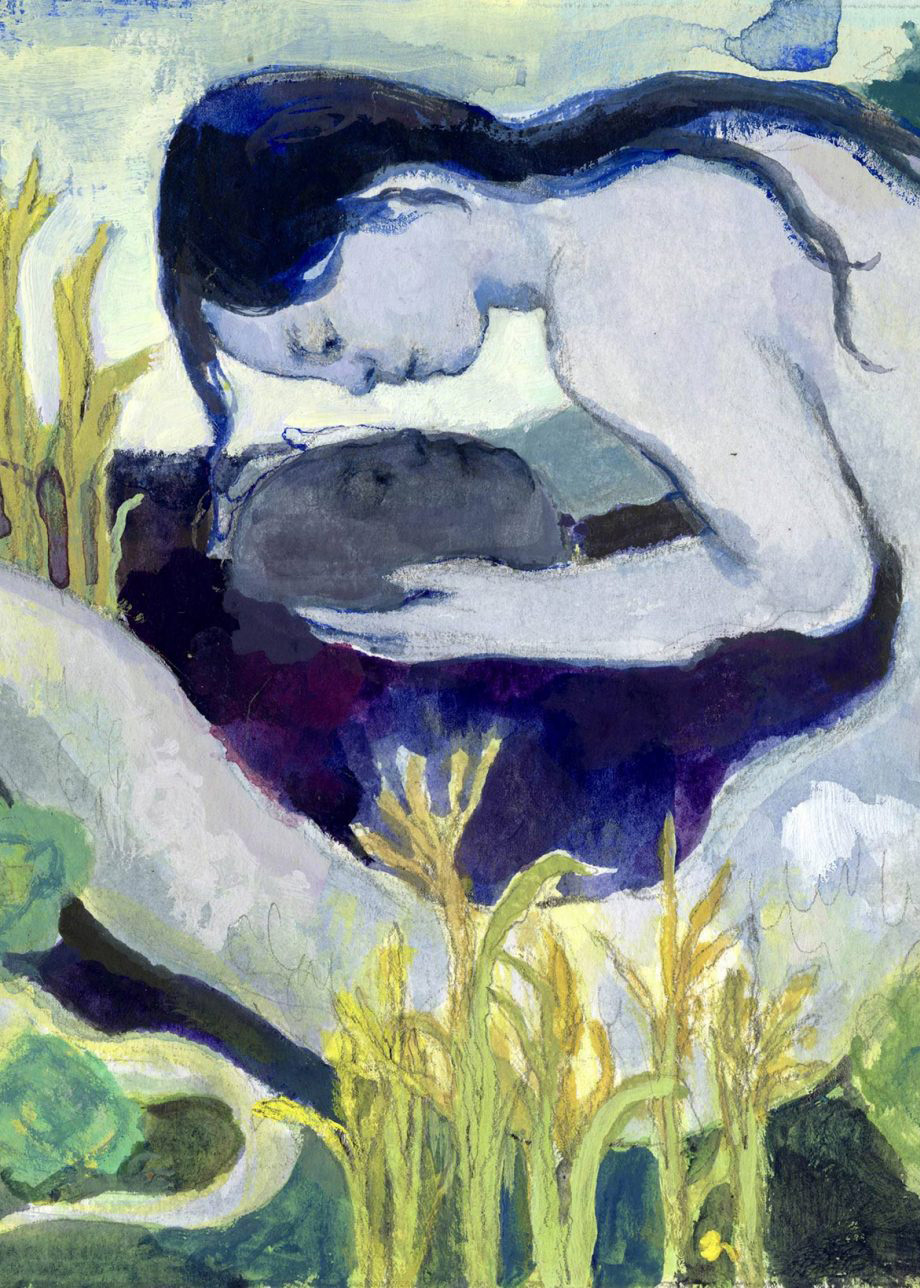

See, Lat, and their three children forage for fish and mushrooms as they try to hold on to their traditional way of life in the Areng Valley of Cambodia.

The hot afternoon sun wanes behind the tall kapok trees, and Reem Sav See looks across the rice fields and into the forest, wondering what she and her family will have for dinner that evening. There are wild rambutan leaves (sleuk sav mav), bitter melon (sleuk m’reah), and sour eggplant (trop chour) growing in the forest not too far from their hut. They just planted rice a month ago, and the field is covered with little green shoots. See grabs her round, flat winnowing basket (chheng-ay) and calls Virak and Phearum to help her. Chenda, only three years old, is determined not to be left out by her two older brothers, who are closer in age and always playing together without her. She cries, begging to join the expedition. See relents, mainly to quiet Chenda. She hands the basket to Virak while picking up Chenda in her arms. Chenda turns her head toward her brothers and flashes them a smug grin—she’s won again.

They trudge into the forest together, emerging not long after with a basket full of silky, green rambutan and bitter-melon leaves and small golden balls of sour eggplant. See grabs lemongrass growing in the rice fields that she planted not too long ago and plucks a few yellow winter-melon blossoms (pka tralach), blooming from the vines. She pleads with Virak and Phearum to pick her a couple of melons, if they haven’t already snacked on all the baby fruits. All of this See throws into a pot with salted fish that her husband, Vann Lat, caught in the Stung Chhay Areng River with the boys a few days before. She crushes the sour eggplant into a paste and adds fish sauce and dried chilies.

The soup is bright and clear, shimmering with dark-green leaves and pale-green chunks of melon. The fishiness of the broth is delightfully balanced by the bitterness of the bitter-melon and rambutan leaves and the sweetness of the winter-melon fruit and blossoms. See cooks all of this on a fire just outside the hut, and Lat helps her, making and tending the fire, stirring the soup and tasting it, offering suggestions to add more salt and pepper if needed. When the soup is done, the pot is carried up to the hut, and See ladles the soup into bowls, which the family shares, spoon by spoon over fragrant rice harvested from the season before.

The family shares not only food but also stories. Earlier that day, Virak and Phearum foraged for wild turtle-nail berries (krachk a ntae k) with their aunt, Doun. Virak is eager to boast how high he climbed the tree. Phearum sits up straight, determined to outdo him, and projects his voice like a megaphone. See and Lat laugh at their exaggerations.

See and Lat and their children live in Areng Valley at the foot of the Cardamom Mountains in southwest Cambodia. During the planting and harvest seasons, they live in a small hut in the middle of the rice fields—a rice oasis surrounded by forest. All of their vegetables come from the forest or the small garden they’ve planted in the rice fields. Their fish come from the river that flows not too far away. The people of Areng Valley have often described the forest as their market, where no money is exchanged; the balance here is kept through respect and gratitude.

Areng Valley is dotted with forests and meadows. During the dry season, the meadows turn a rich golden brown. When the frogs begin their croaking, one knows the rain will come—and, with the rain, the first signs of plenty. Green shoots will cover the ground, flowers will begin to blossom, and small ponds will appear, scattered throughout the meadows. In the ponds will be fish, crab, and frogs that have hatched from eggs buried in the deep, moist mud. At this time, one need only cast a net or dip a fishing basket into the pond to catch enough for an evening’s meal, which is all that has ever been needed before. But with each passing year, the catch becomes more scarce.

The people of Areng Valley are descendants of the Chong, known as Khmer daem, or the “original Khmer.” They have lived in this valley and on this land for over six centuries and have viewed this land as sacred. Here, “sacred” refers not only to the spirits that protect these fields and forests but also to the bountiful food this rich land offers. When See and Lat enter the forest, they remind their children to tread lightly; to not speak ill of the forest and spirits; and—when harvesting fruits, leaves, vegetables, mushrooms, and fish—to seek permission before taking, to never take more than one needs, to give babies and new shoots time to grow, to save today in order to harvest more tomorrow. In this way of life, when one abstains, one is rewarded with infinite gifts from the land. By taking less, one is promised more.

During the Khmer Rouge period, which lasted between 1975 and 1979, Areng Valley, a formerly isolated community, witnessed the first invasion of new ideas. The main village once bordered the forest. When the Khmer Rouge arrived, all of this forest was cut down, including a spirit forest that once housed an old temple. See’s mother remembers what her elders told her: When the trees were cut down, they heard screams coming from the forest. They weren’t sure if the screams came from the trees or from the spirits who lived in this forest. Once the forest disappeared, cattle grazed in the meadows and defecated all over the land. Polluted with dung, the land became sap, meaning, literally, “bland” and “tasteless”—no longer possessing the spirit of its former life; no longer rich; no longer sacred. And once the land and forests were no longer respected and revered, it became possible to cut down more trees and destroy more land and forests.

After the Khmer Rouge fell, Cambodia quickly moved toward an open-market economy. An influx of new people also arrived in Areng Valley, interested in exploiting this land for timber and farmland and imparting new market ideas into the Areng way of life: Cut down the trees. Fish the rivers. Take more before someone else grabs it before you. Use pesticides, herbicides, and fertilizers to ensure a bigger yield. In this way of life and this way of looking at the world, the land becomes finite. There are no ongoing gifts, no gratitude or respect, only resources to exploit and profit from. When one takes more than is needed, these resources become more and more scarce. By taking more, one is promised less.

See and her sister, Touch, prepare their baskets to go fishing in the ponds that form in the meadows not too far behind their homes. They walk out to the meadows and discover that all of the ponds have been emptied of water and only soft, slushy mud remains. They notice a pipe extending out of a dry pond and a motor sitting next to it. They recognize the pipe and the motor. They know these items belong to someone in the village who had been draining the ponds to harvest and sell the fish. All of the fish in these ponds would have fed not one family but an entire village for an entire season. Now no one else can harvest from these ponds, and the natural fish life cycle has ended as well.

In this way of life, when one abstains, one is rewarded with infinite gifts from the land.

See and I often speak about these changes. Nature has its own time and seasons, she says. Like the flow of the river or a wild-mushroom harvest, nature cannot be controlled. Over years of foraging, I’ve come to know and understand place and to develop a way to be with the land. To be with See and her family is to know that this is much more than a search for nutrition.

Through feeling, a forest is revealed. Even in a place far away from Areng Valley and nearer to my home—among coastal redwood trees, bishop pines, Douglas firs, hemlocks, and oaks, where there is rich habitat for chanterelles, black trumpets, yellow foots, hedgehogs, porcini, candy caps, and even the deadly amanitas—there is a silence that suggests touch: The sensation of the mist that seeps through the trees and touches my skin. The cool air beneath the shade of trees. The dense leaves that crunch beneath my feet. The moistness of the soil that crumbles between my fingers. The changes through the year. The whole of the relationship between the ocean and the trees, the moisture and the soil, the trees and the mushroom.

I still remember one of the first meals See shared with me. It was a delicate mushroom soup made with bright-yellow mushrooms she’d harvested from the forest. They came only at that time of year, in May—after the rains and awash in the sun. It was like eating sunlight. The flavor was light but bold, savory with a hint of sweetness. A sweetness I imagine would come from a mushroom nourished by decomposing bark and leaves, moist spring rain, and the day’s sun.