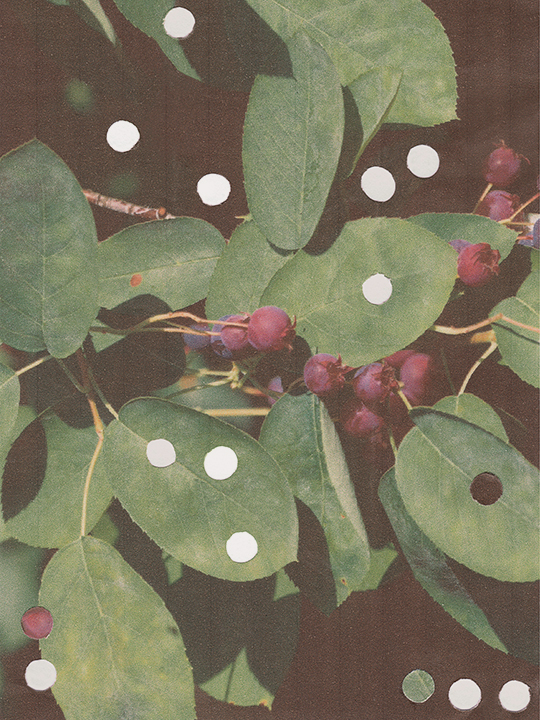

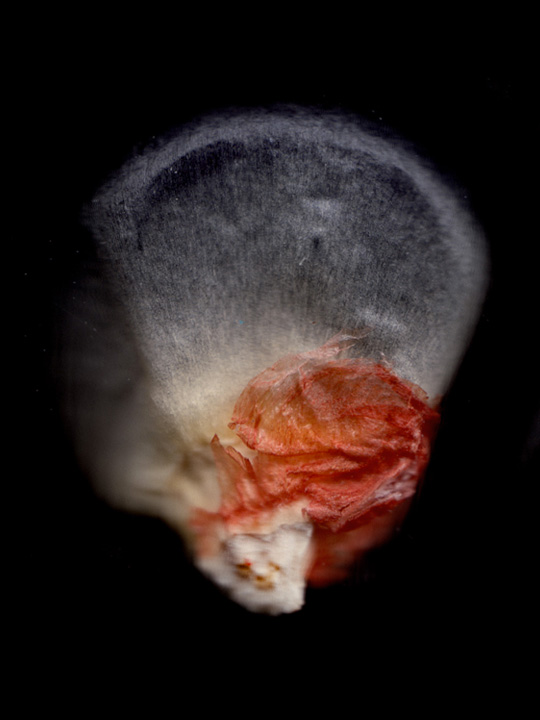

Artwork by Tony Drehfal

Skywoman Falling

Robin Wall Kimmerer is a mother, scientist, professor, and enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation. She is the author of Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants and The Serviceberry: Abundance and Reciprocity in the Natural World. Robin is a MacArthur Fellow and was awarded the National Humanities Medal. She lives in Syracuse, New York, where she is a SUNY Distinguished Teaching Professor of Environmental Biology and the founder and director of the Center for Native Peoples and the Environment.

Tony Drehfal is a wood engraver, printmaker, and photographer. He lives and works in Wisconsin, where he has been making wood engravings since 2002, often inspired by the lakes and woodland landscapes north of his home. Tony is also the editor for Block & Burin, the newsletter of the Wood Engravers’ Network.

In this excerpt from the new introduction to her acclaimed book Braiding Sweetgrass, Robin Wall Kimmerer draws upon the creation story Skywoman Falling and the wisdom of plants to guide us through our present moment of deep uncertainty. Her words of hope, transformation, and courage feel especially poignant at this moment as we look to find ways to heal and address the monumental challenges that lie before us.

I began writing Braiding Sweetgrass in what seems, from this moment in the midst of a global pandemic and the upheavals it has generated, a more innocent time, when climate catastrophe was a hot glow on the horizon. We could smell smoke but our home was not yet engulfed in flames. There was guarded optimism for leadership on climate change and justice for land and people, human and otherwise.

A lot has happened since in climate urgency, with the political pain of vile Windigos come to office and all the wounds they have inflicted. I don’t need to say more. This evidence might suggest that the medicine of plant stories has not worked very well to heal our relationships with land and each other. The powerful purveyors of destruction are still in power, the skies darkening. But as always, I take my guidance from the forests, who teach us something about change. The forces of creation and destruction are so tightly linked that sometimes we can’t tell where one begins and the other leaves off. A long-lived overstory can dominate the forest for generations, setting the ecological conditions for its own thriving while suppressing others by exploiting all the resources with a self-serving dominance. But, all the while it sets the stage for what happens next and something always happens that is more powerful than that overstory: a fire, a windstorm, a disease. Eventually, the old forest is disrupted and replaced by the understory, by the buried seedbank that has been readying itself for this moment of transformation and renewal. A whole new ecosystem rises to replace that which no longer works in a changed world. Braiding Sweetgrass, I hope, is part of that understory, seeded by many thinkers and doers, filling the seedbank with diverse species, so that when the canopy falls, as it surely will, a new world is already rising. “New” and ancient, with its origins in the Indigenous worldview of right relation between land and people. What the “overstory” of colonialism tried to suppress is surging. It is the prophesied time of the Seventh Fire, a sacred time when the collective remembering transforms the world. A dark time and a time filled with light. We remember the oft-used words of resistance, “They tried to bury us, but they didn’t know we were seeds.”

It’s as if we can see the world we want to live in just over time’s horizon; the question is how do we get there? It’s a question familiar to Sweetgrass, unable to leave one place and travel to a better one by seed. Ki* relies on humans to carry rhizomes, the ones who can easily cross distance and boundaries, who know that whatever we wish to see on the other side of the narrows of this ecological and cultural crisis, we must pass lovingly from hand to hand.

The mythic story of Skywoman Falling is the heartbeat of Braiding Sweetgrass, both an opening and a closing, enfolding the stories between. The version shared in the first edition is the most widely told account of the epic, but it is not the only one. There is always the deep diving Muskrat and the earth on Turtle’s back. The rescue by the Geese and the gifts of the animals are a constant, as are the seeds Skywoman brings, initiating the covenant of reciprocity between newcomer humans and our ancient relatives. The detail that varies from one telling to another is just how Skywoman finds herself falling from one world to the next. The common version is that she slips, the earth giving way at the edge of the hole in the sky where the great Tree of Life had fallen. It is an accident, with mythic consequences—and so it begins.

But in other tellings, this was no accident. In one version, she was pushed. In another she was thrown—not from malice but because she was needed for the sacred task and needed “help” in leaving her beloved home for the next. In every version I’ve ever heard, Skywoman was an accidental and possibly an unwilling traveler to the next world, like a seed on the wind.

As I look around at the strong women I know, Indigenous and newcomer, survivors and thrivers, teachers, artists, farmers, singers, healers, mothers, nokos, aunties, daughters, sisters holding together families and communities and leading the way to a new world, I have a hard time seeing our Skywoman as an unknowing and passive emissary. No. I see her standing at the edge of the hole in the sky, her belly planted with new life, looking down into the darkness. Guided by the shaft of dazzling light shining through, she catches a glimpse of the world that waits for the seeds she carries, plucked from the Tree of Life. With all humility and respect for the teachings of this sacred story, I cannot help my imagining forward to this moment on the circle of time. What if, with full agency, she spreads her arms, looks over her shoulder, feels her child stir within and then—what if she jumps?

She is a woman with a duty to safeguard life. Just as women have done throughout our painful history, carrying life through times of starvation and disease, on the long walks of removal, hiding children from the boarding schools and embracing the ones who came back, fighting pipelines, protecting water, saving the seeds, learning the language, holding the ceremonies, honoring the earth… Skywoman’s descendants are not women who would step away from the edge, if it meant the protection of life.

As a society we stand at the brink, we know we do. Through the hole that opens at our feet, we can look down and see a glittering blue and green planet, as if from the vantage point of space, vibrating with birdsong and toads and tigers. We could close our eyes, keep breathing poison air, witness the extinction of our relatives and continue to measure our worth by how much we take. We could cover our ears to our own knowing, back away from the edge and retreat to the gray decline.

In this time of transformation, when creation and destruction wrestle like Skywoman’s mythic grandsons, gambling with the future of the earth, what would it take for us to follow Skywoman? To jump to the new world, to co-create it? Do we jump because we look over our shoulders at the implacable suffering marching toward us and jump from fear and portent? Or perhaps we look down, drawn toward the glittering green, hear the birdsong, smell the Sweetgrass and yearn to be part of a different story. The story we long for, the story that we are beginning to remember, the story that remembers us.

What does it take to abandon what does not work and take the risks of uncertainty? We’ll need courage; we’ll need each other’s hands to hold and faith in the geese to catch us. It would help to sing. The landing might not be soft, but land holds many medicines. Propelled by love, ready to work, we can jump toward the world we want to co-create, with pockets full of seeds. And rhizomes.

This op-ed is excerpted from Robin’s new introduction to the hardcover special edition of Braiding Sweetgrass, available from Milkweed Editions.