Reseeding the Food System

Rowen White is a Seedkeeper from the Mohawk community of Akwesasne and an activist for Indigenous seed sovereignty. She is the director and founder of Sierra Seeds, an organic seed cooperative focusing on local seed production and education, based in Nevada City, California. She teaches creative seed training immersions around the country within tribal and small farming communities.

Emmanuel Vaughan-Lee is an author, Emmy- and Peabody Award–nominated filmmaker, and a Sufi teacher. He has directed more than twenty documentary films, including Taste of the Land, The Last Ice Age, Aloha Āina, The Nightingale’s Song, Earthrise, Sanctuaries of Silence, and Elemental, among others. His films have been screened at New York Film Festival, Tribeca Film Festival, SXSW, and Hot Docs, exhibited at the Smithsonian Museum and London’s Barbican, and featured on PBS POV, National Geographic, The New Yorker, and The New York Times Op-Docs. His first book, Remembering Earth: A Spiritual Ecology, is forthcoming from Shambhala in summer 2026. He is the founder, podcast host, and executive editor of Emergence Magazine.

In this in-depth interview, Rowen White shares what seeds—her greatest teachers—have shown her: that resilience is rooted in diversity, and that all of us carry encoded memories of how to plant and care for seeds.

Transcript

Emergence MagazineWell, it’s a real pleasure to talk with you this morning, Rowen. I wanted to start off by getting a sense of what your relationship with food, and farming, and seeds was like growing up.

Rowen WhiteFirst and foremost, as a Mohawk woman, culturally we’re intimately connected with food and farming because of our ancestral traditions, and our cosmologies, and our stories. But unfortunately, due to the impacts of colonization, acculturation, and displacement of our people, when I was growing up, the last people that I knew who farmed and gardened as a livelihood were my great-grandparents. My grandparents grew up on a farm, but they were all part of what we call the boarding school generation.

They were taken away from their families, and the connection to the land—and the connection between food and seed, from a cultural perspective—was really severed. So I was always curious, always pounding rocks and getting my hands in the earth. My mom had a little garden out back and I used to grow these little pumpkins. Everybody always used to say that I have two ancestors in my lineage—my great-grandfather, Alex White, and my great-grandmother, Anna Jacobs—and that there was some of them coming through in my curiosity and fascination with the natural world and with food and growing things.

When I was seventeen, I found myself on an organic farm in western Massachusetts, and the magic of seeds, the magic of biodiversity, and this whole doorway of inquiry opened up for me as a young woman. I was tasked at this particular farm with growing heirloom tomatoes. And at that point, as a Mohawk woman who had grown up eating a lot of canned food and a lot of processed food because of some of the gaps in traditional foodways knowledge, I didn’t realize that tomatoes came in any other color but red.

So, I was growing these tomatoes that were purple, and orange, and fuzzy, and this whole prism and rainbow of color and diversity. I was so fascinated by that particular discovery. And I realized that not only did these seeds have places where they originated from—homelands that were oftentimes written in the descriptions on the seed packets or in these seed catalogs—but they also had people who they had been intimately connected with throughout time. People had been in these intimate and very connected relationships to these seeds.

Equal to my joy in that moment—being on that farm and learning about all of these tomato varieties that we were planting in the greenhouse, that was a cornerstone moment—I remember, sitting on this dusty farmhouse floor in New England, that palpable feeling of grief at the same time, of this longing, of saying: What were the foods that fed my ancestors? What were the seeds that fed my ancestors? There was this joy and grief mingling together, and at that moment I told myself, I want to find out the foods and seeds that fed my ancestors.

That was twenty-three years ago, and I’ve been on a path of inquiry ever since—going back to my home community, asking elders and family members, What foods do you remember eating as a kid? What did they look like? I found some really unlikely allies along the way. It has definitely helped me: looking at this modern world and who I was as a Mohawk woman, the foods and seeds really helped me to reclaim a sense of identity and find my way home, to find that purpose and help me to restore a sense of connectedness—a restory-ing of my life through food and seed.

They’ve been very impactful. And I always tell folks along my road that the seeds have become my teacher. They brought me through a very unconventional rite of passage, to learn who I was as a young woman. I didn’t necessarily have a ceremonial rite of passage, but those seeds and foods became my aunties and my grandmothers, teaching me what I needed to know along that pathway towards self-discovery as an Indigenous woman living in this modern world. They helped me to find meaning and purpose in my life, and so I’m forever indebted to them for helping me in that way.

EMSo, your relationship to seeds, which really blossomed on that farm, led to reclaiming and reconnecting to a culture that you were distanced from?

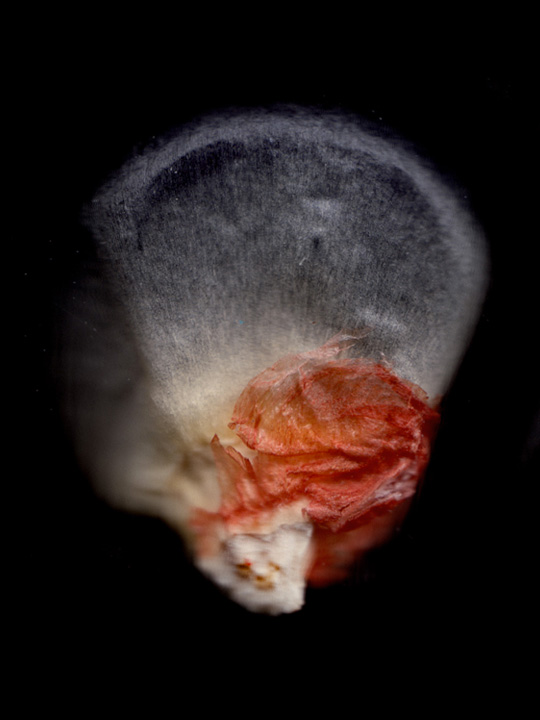

RWYes, there was definitely a reclamation and a restoration of relationship that was necessary, because, for many Indigenous peoples who live on Turtle Island in North America, our foodways were violently dismantled for very specific reasons: to disempower and control us. A lot of my inquiry in the last many years has been around this inextricable link between cultural revitalization and the restoration of our traditional foodways. There are inherent memories, and inherent knowledge and wisdom, encoded in those foods and seeds: like the corn that I have here in my hand. They’re a way in which this memory has been encoded since time immemorial, of all these teachings, of all these ways of being.

When we, as Indigenous peoples, begin to reclaim our culture and restore relationships to the land and to all our relations around us, I think these foods and seeds have a really important role to play in that revitalization of culture.

EMWhat was it like for you, as a young woman, being opened up to this whole world through the seeds you held in your hand? Personally, what did it reveal to you and change?

RWI think it gave me renewed hope. As Indigenous people, growing up in a time and space where we have to oftentimes walk in two worlds, there are a lot of conflicting messages that we get. On one hand, you have this identity as an Indigenous person, but you’re walking in a world that is very colonized and isn’t always a safe space to express those parts of yourself. [Since I was a] young woman, these seeds have given me a trellis of hope—in a time when there’s a lot of despair in the communities we live in, there’s a lot of intergenerational trauma that’s unresolved, there’s a lot of unresolved grief that comes from the imposed shame from colonization and acculturation. These seeds and foods have become my trellis of hope in a lot of ways. They gave me renewed focus and purpose at a time in my life, as a young woman of sixteen, seventeen—at that time in our lives and that stage of our development as humans when we’re always [asking]: Why did we come here? What is our purpose here on Earth?

I feel like they’ve been the ones who’ve given me purpose. Everyone, along their path, hopefully at some point in their life, finds something they feel passionate about. I feel like seeds were my first love, in a way—something that I fell so deeply enamored with, just in terms of their beauty, the way that I feel when I look at them, the ancestral memories that they recall inside my body. In some ways, over the years, I’ve grown to know that they’re just rehydrating in my blood and in my bones these original agreements that my ancestors made with these foods a long time ago. It’s a natural thing that so many of us have forgotten, and we’ve forgotten that we long for that relationship to our food.

Over time, I’ve learned that the joy that I feel, the passion I feel, is the restoration of these long forgotten original agreements that I have in my blood and my bones. It’s a good feeling, to feel like they’re coming back to life, and that they help inform me as I walk in the world. They offer a set of guiding principles and offer a set of core values that really guide the way in which I move in the world, which is vitally important at a time when there’s so much disconnection, and there’s so much confusion on the Earth. I think so much of the current predicament that we’re in, as a society at large, is that there is a lot of grief of disconnection. I don’t think any one of us is untouched by that grief of disconnection.

I think that there are many ways to find our way home, so to speak, to feeling more at home inside our bodies and at home on this Earth that we inhabit here. My pathway home has been through finding meaning in this food and being one person of many who can nourish and make people feel really healthy and good from the very core.

EMYou’ve spoken about the dangers of our experience in relationship to food being disconnected or disassociated from seeds. And that really struck me, for as much as people seem to be more aware of the importance of a healthy food system, you don’t hear seeds mentioned very often. Why do you think this is the case? And what happens when this relationship becomes severed?

RWThat’s a great question. Again, through a multitude of variables over the last many decades, and centuries even, there is a way in which we’ve abdicated our relationship to seeds, [leaving it] to somebody else. We’ve been disempowered from understanding the very intricacies of how food even comes to be on our plate. So many children these days have no idea that so many of the foods that nourish them every day trace back to the generosity of a seed; that at the heart of all of the foods that come onto our plates, all the multitude of foods that nourish us, [are] seeds.

I do think there has been a manufactured disconnection within our food system to disempower people. I think part of my mission—and part of the seeds’ mission that comes through me, I guess is a better way of saying it—is that we need more seed literacy in our food systems, and in the way that we make change in our food systems. What that comes back down to is an honoring of origins, an honoring of what I call intimate immensities. A seed is so big and so small at the same time. I think the more that we can continue to advocate for seeds and the multitude of varieties that make up our food system—the more that we can create more literacy, cultivate more literacy, and advocate for [seeds]—the healthier and more durable our food system will be.

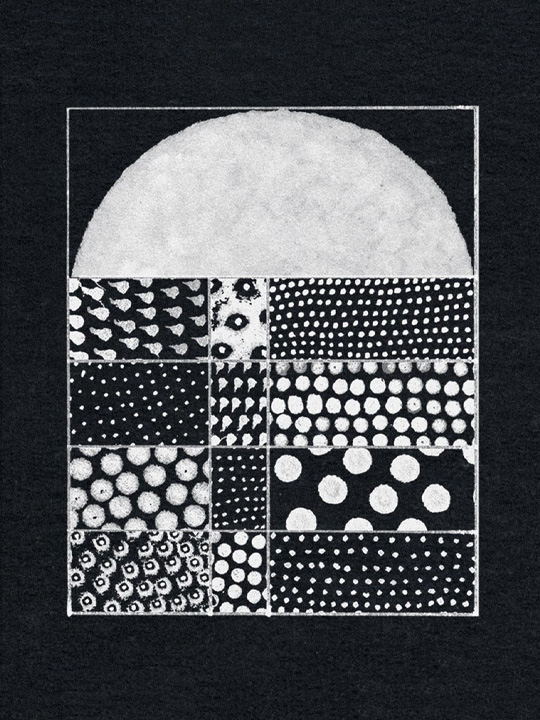

What I’ve learned along the way is that our resilience is rooted in that diversity. The reason why humans have been able to adapt and evolve to the ever-changing face of our Mother Earth is because of that biodiversity, and being able to be resilient in the face of that change. Seeds adapt so quickly in the face of that change. And what concerns me is that much of our food system rests upon a very narrow bottleneck, or a narrow pinnacle, of just a handful of varieties.

The genetic erosion that has happened over the last several decades—from a time when there was a multitude of different varieties of all different types of crops that fed and nourished people, now down to just a handful of varieties that make up the food that ends up on our plates—that’s troubling to me, because it means that our food system is less resilient. I feel like the key to resilience in our food system is dependent upon the diversity that’s inherent in the seeds that are the foundation of that food system.

A big part of my work is to advocate for people to not forget about the seeds, and not forget about our relationship to them. When I go into spaces to teach or to share story, I oftentimes bring seeds and food with me, and there is a palpable sparkle in people’s eyes and a joy that people get when they gather up a handful of these beautiful seeds. I think it reminds them of what’s possible, of the beauty that’s possible in our food system, and also a food system that’s rooted in a culture of belonging.

If you look at the seed that I’m holding in my hand, it’s this Navajo Robin’s Egg corn; and the corn herself has these blue speckles on this white corn. What they say is that this is reminiscent of rain on dust, that this is reminding us of how important the rain that falls on the Earth is. It’s so vital to our survival as humans. Encoded in these seeds are ceremonies, and seed songs, and stories and lineages, and migration stories. So when we have a relationship to these seeds, and know them by name, and eat them at our kitchen tables, then we begin to call that back into our lives again—all of that richness that those memories bring; that we would have ceremonies, and songs, and dances that honor the food that makes it to our table; and that we would have a food system that embraces deep story and deep connection at its very heart.

EMYou’ve talked a lot about how seeds carry much more than the blueprint of the plant that they can become. They are much more complex and intertwined with humans and our story than we realize. As you just described, they carry stories, or they tell stories. You said they hold lineages of relationships, and earlier you also talked about how those relationships hold trauma and grief, as well as joy. Could you talk a little bit about this?

RWAbsolutely. We are all indigenous to somewhere, and we’re all called in this time to be in inquiry about decolonizing ourselves and our relationships; and that process is multisensory. We can’t just think our way out of the predicament that we’re in. It really requires us to reimagine the way in which we engage with the world from a multitude of senses. In some ways, when we eat this corn or eat these traditional seeds, they go inside of our bodies, and rewire us, and reconnect us in ways and places that we can’t even think into. We don’t even know that there are places that need to be healed inside of ourselves. The seeds and the foods have the capacity to do that.

We had a beautiful gathering around the central fire of the Haudenosaunee people. As a Mohawk woman, I am part of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, and we had a gathering to really honor the seed keepers and the seeds of our confederacy in 2016. We gathered around with that particular purpose—to really look, as a nation and as a gathering of nations, to say, what are we going to do to keep the seeds alive for the generations yet to come?

This elder talked about how the seeds were the reflection of the people, and when the people are suffering or when they’re being challenged in the world, the seeds are also suffering. When we strengthen the seeds, we start to focus ourselves on the seeds or on the foods. You could replace seed with a buffalo, or a salmon, or whatever particular traditional food is at the center. When we begin to strengthen the seeds, the people inherently become strengthened themselves.

As I went away from that gathering, I was driving across the heartland, the middle of this country. What we know about the middle of this country is that there’s endless fields of genetically modified corn seed and soybean. I remember driving across—it was in May, so everything was just a beautiful sprout—and I remember driving across those roads, and the fields were just sprouting. I remember seeing the beauty in those fields and singing seed songs to those fields, and then I remembered in my mind that they were GMO seeds. So many of us villainize the seeds, but really, those seeds have been so exploited themselves by the larger capitalist system.

I remember thinking that thought, which had been seeded to me by my elder, about how the seeds were a reflection of the people. I remember driving through those cornfields and thinking, these seeds are a reflection of the American people. These seeds are a mix of tattered origins that have been cut and spliced together. In my mind, I said, these are brokenhearted seeds being planted by brokenhearted people who have no idea of who they are and where they come from; so they make seeds that look like themselves. I’ve shared that sentiment with a lot of people, and people find a lot of truth in that way of looking at things. How can we restore a food system that has inherent, whole seeds at the center, that restores a sense of pride and resilience and a sense of identity to the people in this country? I feel like that is how we are going to address the syndrome. I think it’s a syndrome of genetic modification.

It’s actually a symptom, I guess, of a deeper syndrome, which is a people disconnected from who they are and where they come from. And there are a lot of us, many of my elders and teachers, who speak of a time where we need to reseed the people. We need to reseed not only the physical seeds, the good seeds that create the foundation of our food system, but also those songs and those stories and that sense of reverence, that sense of love and connection to the food that ends up on our plates. Otherwise, we create a system of exploitation that continues to look at food and seed as dead, inanimate objects. Whereas in my world view, and in many of our Indigenous world views, these seeds are our relatives. We are direct lineal descendants of these seeds and foods, so it’s our responsibility to care for them and protect them.

EMYou’ve talked a lot about that challenge to the dominant Western world view of seeds as an inanimate object, but as you’re describing them, they come alive as if they’re relatives and as if they’re kin. And just as we’re seeking to reconnect to seeds and food in a meaningful way, it seems like you’re talking about how seeds themselves are yearning for human relationship, and that they were left behind as people moved away from a direct relationship with growing food. How have you experienced seeds communicating this yearning? How are they talking to you about what’s been happening to them?

RWI feel very humbled and very honored to have seeds be one of my great teachers in this life, and I sit in circle with a number of Indigenous seed keepers who feel the same way. It feels like we’ve become vessels and voices that speak on their behalf in this time when so many people have forgotten the immensity of a seed and the power of a seed. I’ve seen and heard stories of corn dances and songs coming back through young people who’ve been immersed in community gardens, where these old forgotten ways are coming back again through the hearts and intuitions of these young people.

These songs and these dances that were perhaps thought to be extinct or forgotten have been returning, because we’ve been restoring our connection and relationship to seed. As a Haudenosaunee woman, a Mohawk woman, our connection to these seeds draws back all the way to our original creation story, where these seeds and foods emerged from the dying body of the daughter of Original Woman. They came from her body as a gift to her twin sons, so we would forever be nourished by these foods and seeds. Therefore, it was our responsibility to acknowledge that we were bound in a reciprocal relationship to them, that they were our relatives, that we were to take care of them, and that part of their duty was, in some ways, to lay themselves down in sacrifice for the nourishment of the human relatives.

As we begin to remember—I always think about “remember” as meaning “to put things back together.” You’re re-membering; you’re putting things back together again. As we begin to put the pieces back together of our food, of the way that we feed and nourish ourselves, I think that the seeds have a lot of ways in which they’re animating us—and animating our hands, and hearts, and bodies—to grow a way of nourishing ourselves and sustaining ourselves on the land that honors the grand lineage of ancestors, human ancestors and non-human ancestors, who went through so much adversity, and joys, and all of what it means to be human, so that we could have food and seed here today.

I think a lot of us in this movement make our lives love poems and honoring songs to ensure that we’re not that generation that forgot, that didn’t keep that chain of stewardship and lineage alive for those yet to come. It was told to our elders, as Mohawk people, that the seeds came from the Sky World, which is where we came from before we came here to this world. And if we were to continue to abdicate our relationship to those seeds and foods, then those foods and seeds would go away, back to where they came from. Many elders and people from our community made a lot of ceremony, and a lot of prayer, and a lot of offerings to ensure that those seeds were reminded that we didn’t forget about them.

We make renewed commitment in this work that we do to make sure that we don’t forget, and to ensure that we have a bundle of seeds that’s in better shape than when we received the bundle. That’s kind of the inherent lesson. In our culture, we believe that we don’t own the seeds, but we borrow them from our children, and it keeps us in a really good mind to remember that these aren’t ours. We borrow them from those yet to come, so it’s our responsibility to make sure they’re in really good hands and in good shape for when those next generations come to this Earth.

EMEarlier you spoke about agreements that were made between your people and the seeds—between seeds, plants, and humans. You’ve said that these stories, these agreements, have mostly been forgotten, and that there is a correlation between this and the problems we’re experiencing in our food systems. I’m curious to hear, what are these agreements that you’re speaking about?

RWI think so many of us have agreements. I like to remind folks that there was a time on Earth when agriculture didn’t exist. There were wild plants and animals, and people have always been in relationship to them. And I think agriculture as a current concept looks very different in lots of ways. We humans have been shaping the landscape since time immemorial and have been in collaboration with all manner of different wild plants and animals for a long, long time. But there was a time in history (some people say it was around 10,000 years ago, although you never know) when there were wild plants—I feel like it was an invitation from the wild, and this is how it’s been told to me—there were wild plants who could see the potential of being in a different sort of relationship with humans, and they invited us into this co-creative dance that we call agriculture.

The plants gave up a little of their wildness, and we humans gave up a little of our wildness too; and we came into this covenant, this sacred covenant or this marriage. In some cultures, it’s spoken of as a marriage. We came into this relationship, and part of those agreements were to take care of one another. We were going to be bound in this reciprocal relationship, to care intimately for one another as we move forward. So the foundation of those agreements is that understanding of reciprocity, understanding that when you do well, I do well, and that it is a courtship too. There’s an aspect of wanting to ensure that they’re well taken care of, not just because it means nourishment and food for us, but because there’s a deeper sense of love and relationality in that connection.

Then there’s a multitude of agreements—that I think is different for every culture in terms of what caring for a seed looks like. What are the systems? What are the ways that we grow? What are the ways that we cook? What are the protocols? For instance, as a Mohawk woman, there are agreements that I can’t speak unkind words around seeds. Part of the cultural bundle that we have is that we’re supposed to keep a good mind when we’re around seeds, because they’re very sensitive. If they hear us speaking harsh and unkind words to one another around them, they become brokenhearted, and they don’t have the vitality to grow. Part of that agreement that we have with them is that we keep a good mind, a good heart, around them.

There’s a multitude of layers of agreements. Some of them are around our ceremonies. There’s a need in this time for us young people to step up and look to our elders and say, “We’re here. We don’t forget. We understand how important our memory of these ways is to the survival of our people.” Because as Mohawk people, our ceremonial cycles, our ceremonial calendar, is an agricultural calendar. If you look at the cycles in which we pray and make offerings, all of this is in direct alignment with the seasonal cycles, as it relates to how we feed and nourish ourselves. So, if we are no longer feeding and nourishing ourselves through the act of co-creating with the land and with the seeds in this way, then the process of going through those rituals and ceremonies becomes just a husk. The germ is no longer there. The heart of the purpose of why we do that is no longer there, if people aren’t engaging in meaningful relationships to those foods and seeds.

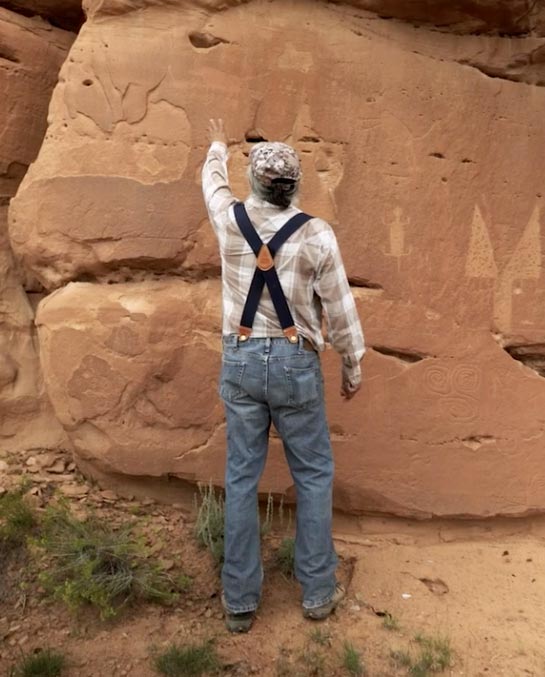

EMOne of the strands of your work focuses on returning seeds to their original keepers, birthplaces, and lands. Can you talk about why this is so important?

RWFor a multitude of reasons, many seeds have moved from their lands of origin, from tribal communities outward. We know that seeds move and migrate. It’s naturally a part of a seed’s journey to want to move along kinship routes and trade routes. Corn, herself, moved from a very fertile valley in Oaxaca to all regions of the globe, through trade and through kinship routes.

But during the time of immense colonization, and displacement, and acculturation in the last several centuries in North America, there have been some disconnections between people and their seeds, and also people and their ancestral lands. Through things like the Long Walk and the Trail of Tears, people have been relocated forcefully to other places, sometimes carrying those seed bundles with them. And then sometimes those seeds were traded out, but they didn’t stay alive in their communities of origin; and they found themselves in places like the USDA seed bank and public access seed banks, like Seed Savers Exchange in Iowa, and the Field Museum in Chicago, and the University of Michigan—many places, where these seeds have found themselves away from their communities of origin.

As we’ve been working with the Indigenous Seed Keepers Network, as a part of the larger Indigenous food sovereignty movement in North America, one of the key questions and key challenges or problems that we’ve seen is that tribal communities are needing access again to culturally significant seeds, that some of these seeds are no longer available in their communities because of those eras of transition. So many people are familiar with the word “repatriation,” which oftentimes is used when Native communities are reclaiming funerary objects or objects that have been stolen or removed from tribal communities, and also ancestral remains—when those are being returned from institutions outside their community back to their community.

This is a really different and interesting piece—we call this movement “seed rematriation,” because these seeds are alive when they’re coming back home. They’re living relatives, having come home after a long stint away, back to their motherland, back to their mother community. So, the rematriation is harkening to that maternal connection. In many of our communities, there’s a matrilineal connection to Earth. In many of our communities, the bundles of seed are carried by the women, and the ways in which these seed songs and ceremonies are kept alive is in the hands and hearts of women. So, we’re rematriating these seed bundles from institutions back to tribal communities.

Honestly, in all the work that I’ve been doing over the last twenty-plus years, this work of seed rematriation is some of the most impactful work that I’ve seen, in terms of how healing it is. When an Indigenous community works together in collaboration with an institution, or an organization, or a group of people that ancestrally were their adversaries—when they work together with seeds at the center, there is an immense amount of intergenerational healing that happens. When we choose to sort of lay the wounds to the side, and lay our war axes to the side, and work together to grow a garden, to restore these seeds to their rightful places, there is an immense amount of healing that comes with that.

I think in this time that we live in—especially in the political climate that we live in, that speaks so much to division, and to borders, and segregation of people—I think that the message that these seeds are carrying is a message of reconciliation and reparations, of people working together cross-culturally to heal wounds that feel almost impossible to heal.

There are some incredible stories of communities that we’ve been working with, where there’s the generosity of the Indigenous peoples to be willing to trust these allies, and then the allies coming forth with land and resources that help make the restoration of these seed varieties back in their tribal communities possible. I just think that there’s so many messages of hope that come from this movement to rematriate seed.

EMI guess rematriation is almost a broader way of looking at restoring the feminine back into our lives through our food systems, and also recognizing that our industrial food system, at its root, is very patriarchal.

RWIt’s interesting, because I think it’s not just seeds to people, but it’s people to land. It’s restoring that very sacred, maternal connection that people have to the land herself. There are some incredible stories, like the Pawnee returning home after being away from their ancestral homelands in Nebraska, removed through that Trail of Tears era to Oklahoma, coming home to this land that fed their ancestors for a long time and growing those sacred seeds in that land, and the land remembering, and the land calling the Pawnee people home and reminding the settlers that this is not their land. The land actually has been inhabited for many, many, many more years by these Pawnee people and Ponca people. It’s just really beautiful to see how we’re seeding a new vision of what’s possible as we move forward.

EMYou said that seeds need to be held within a living context that is connected to their stories and web of relationships, which you’ve just beautifully described. But this is very different from storing seeds in a seed bank, which has really taken off, and you’ve got the plans for dealing with an apocalyptic future taking root in different parts of the world, especially in some of these most famous seed banks, in the Arctic, for instance. But what you’re talking about seems so different than that. It doesn’t seem like you’re putting it in a climate-controlled storage facility. You’re talking about putting it in the land and connecting it back to people, and culture, and traditions.

RWWe need a restoration of those living systems that nurture and nourish those seeds into the future, and that’s the true sustainability. Everybody’s always kept a cache of seeds, in clay pots or in little boxes stashed in certain places, because we know that life is uncertain, and we know that Mother Earth’s mood changes from season to season, and sometimes there is crop failure. I think farmers have always had that inherent wisdom to keep some seeds back, which I think is part of those big seed banks’ mentality, that risk management and making sure that there’s some seeds for a time in the future. But what I think that we’ve missed is that we’ve become too reliant on these gene banks, which is what they call them. That name itself indicates the world view, that these seeds aren’t really seen as whole seeds, they’re seen as sort of a mix and match of genes that could be combined and cut and spliced into new variations.

In this movement, we advocate for communities to have seed banks where there’s a backup of the seeds. But so much of the importance of seed restoration—people want to call it conservation, but it really is restoration, because seeds are always changing. They’re forever changing, and humans are one part of helping those seeds to adapt and change to the ever-evolving Earth that we live on. They’re dynamic. They’re ever-changing. So, the seeds need to be a part of our daily lives, because they’re forever adapting, not only to the external conditions of the world around us, but they’re shaped by our hands, and by our aesthetics, and by our creativity as humans. We’re continuing to shape and change them, and they’re continuing to shape and change us. I always laugh when I talk about my work with seeds and work in the garden, and I say, “I always think that I’m growing corn, but I think that the corn is growing me.” How are these foods and seeds shaping us as humans?

So we need to be in that dynamic relationship, season in and season out. If we look at the challenges that lie ahead for our children, in terms of climate change, and all these things that we think about, seeds do have the capacity to help carry us through those uncertain times. They have the capacity to adapt to uncertain futures. But the only way that they’ll be able to do that is if they’re continuing to be grown every day in our lives and adapting season after season. If we store them away in a cold vault for future generations, they’re no longer responding to all the nuances from season to season. When we pull them out of the vault fifty years from now, it’s going to be a very different world from when they went into that vault.

I think the importance of this living context of seed restoration and conservation is so vitally important. I think that those seed banks and gene banks served a purpose in their time, because it was a triage situation, where there was a response to an incredible erosion of genetic diversity. But what gives me hope is working with public access seed banks, like Seed Savers Exchange, that recognize the importance of seeds being a part of our everyday lives and are working towards implementing programs and ways of distributing these seeds back into the communities so that they can be saved as a part of our everyday lives. Wendell Berry always says—I love this quote—“You exploit what you merely value, but you defend what you love.” One of my life’s biggest missions or goals is to get people to love seed and food like they’re our mothers, because when you begin to restore those relationships to food and seed in that way, then you will defend them against all odds. It really does change the face of how we envision sustainability in our food system, moving forward.

EMI really like that, because “food sustainability” is a term that seems to lack any real meaning anymore. It’s thrown around in so many different ways. It’s on packets of everything. And you talk about how it needs to engage the heart, it has to be about love, and also that there needs to be a recognition of the layers of the spiritual and cultural connection that’s present in our relationship to food. That is part of where the evolution of the food sustainability movement needs to go, not just about understanding seeds, but in a broader sense…

RWI think at the heart of what we now see as the organic food movement—so many of the people who revived that idea in this modern context are no different from me, in the way that we approach the work. They were passionate. A lot of those original hippie people who were seeding the organic food movement did it because they had a passion. They had a spiritual connection to the land. They had longing to have more heart engagement, to have that connection to the land. And so what I think has happened is this capitalist co-optation of a movement that made it more about economic sustainability and ecological sustainability in this really intellectual and cerebral sense.

But I guarantee you that a lot of the people who grow our food, who have their hands in the earth, they do it because they care deeply. They wouldn’t be willing to get up day in and day out, to labor under the hot sun, and to do the work that they do if they didn’t love it deeply. I’m always moving in spaces, in conferences and other settings, to open up the door for that to be an acceptable conversation to have, so that we can speak from our heart and we can speak about our passion for this work from a spiritual and cultural level without risking invalidation from the scientific community or from the rational community. Maybe by me being courageous enough to speak in those spaces where that’s not always talked about, maybe it opens a door or gives agency or courage to other people to say, “I have this yearning and this longing to infuse and to weave my spiritual connection and my cultural connection into this work.” I feel like the more of us who can do that and say that this is okay, and this is what we want—I feel like we will then see food systems change in the direction that we all really want it to go.

Vandana Shiva said this to me one time: “Are we feeding the world? Or are we nourishing the world?” There’s a difference there. There’s a difference when we look at what we are doing in this world to nourish the people in our community. And nourishment takes many forms. It’s not just calories. It’s not just protein and vitamins. All of us understand there’s a deeper layer to nourishment and what a good meal feels like when it’s cooked with love, with intention, with meaning. And that’s something I always strive for: to think about how we can continue to make food systems change so that they have that sense of deep nourishment from a multitude of levels, whether it’s spiritual, physical, cultural, or emotional at its core. That’s possible. Yes, it is possible.