Crystal Wilkinson is the author of The Birds of Opulence, winner of the 2016 Ernest J. Gaines Prize for Literary Excellence; Water Street; and Blackberries, Blackberries, nominated for the Orange Prize and the Hurston/Wright Legacy Award. She is a recipient of the Chaffin Award for Appalachian Literature and has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize. Her short stories, poems, and essays have appeared in the Oxford American and Southern Cultures, among others. She is an Associate Professor of English in the Creative Writing MFA Program at the University of Kentucky.

Simone Martin-Newberry is a graphic designer and illustrator based in Chicago. She specializes in print layout, typesetting, hand lettering, and illustration, and has worked with The Guardian US, REI Co-op, the Chicago Reader, Wilmette Theater, and many others.

Remembering her grandmother’s jam cake, biscuits, and sweet black tea, Crystal Wilkinson evokes a legacy of joy, love, and plenty in the culinary traditions of Black Appalachia.

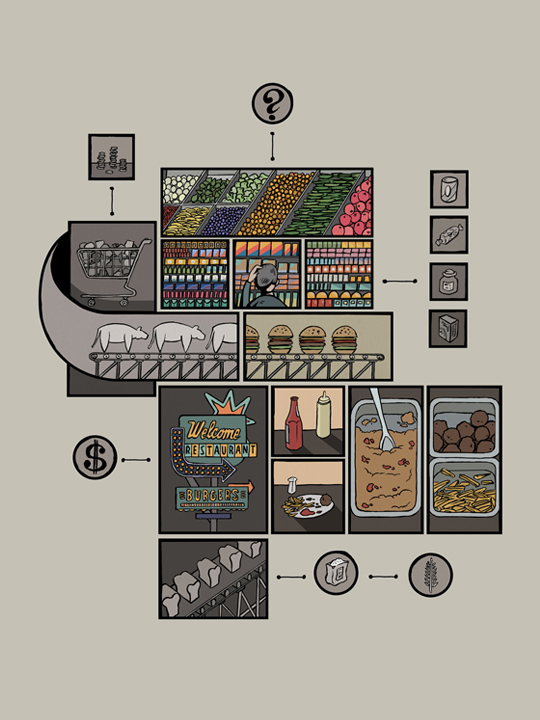

People are always surprised that black people reside in the hills of Appalachia. Those not surprised that we were there, are surprised that we stayed. My family lived in the hills of Kentucky for four generations. My grandmother came from a long line of women who worked hard and cooked well. The long lists of food I’ll describe here will make you think my folks had deep pockets, but they didn’t. Hardworking poor blacks who couldn’t break the barriers of nepotism or racism in education or the workforce, they continued the tradition of farming. Tobacco. Corn. A few head of cattle. A few dairy cows. My grandparents lived primarily off the land. They owned sixty-four acres and had a modest income from the crops they raised. My grandfather prided himself on taking care of his family, his animals, and his land. My grandmother prided herself on making sure her family was fed. I read somewhere once that pride stems from fear. I imagine my grandparents were hungry more than once in their youths, but I never was.

Every morning of my childhood, my grandmother, who stood a little under five feet tall, donned an apron and cooked breakfast. Slow. Precise. Deliberate. She equated food with love, and she cooked with both a fury and a quiet joy.

She fried bacon, sausage, or country ham. She scrambled fluffy yellow eggs with a wire whisk in a ceramic bowl. The eggs came from our chickens. She made biscuits from scratch. The lard was rendered from our pigs. The milk from our cows. She rolled out the dough and threw flour into the air like magic dust. She churned butter, made the preserves from pears, peaches, or blackberries that she had picked herself. We had orange juice and milk. We ate on white plates with blue flowers around the edges and landscape insignia in the center, and more often than not we had brimming cups of sweet black tea that sat in saucers alongside our meal. Our forks clinked musically against our plates. We ate at the kitchen table mostly in silence or quiet conversation.

My cousin Debra calls. She tells me there are green tomatoes at the farmers market. She still lives near our homeplace in Stanford, Kentucky. I live forty miles away in Lexington. Sometimes I drive eighty miles round-trip and buy vegetables sold by my cousin George Alan and his wife Susan, who own a farm, or from other farmers in the area. On the Miller’s Farm Facebook page they post pictures of their bounty, which is as beautiful as any parental brag book. They boast of heirloom tomatoes, cucumbers, cantaloupe, beans, squash, and zucchini. They are carrying on the tradition. Black farmers are nearly extinct.

“Tell me again how you fix greens without fatback?” Debra says.

I tell her:

First you sauté the garlic and onion in vegetable oil in a pot. Then add a pinch of red pepper flakes. Salt. Let the vegetables soften. Wash the dirt from your greens. Slice them longways in ribbons with a butcher knife. Put them in the pot one handful at a time. Cast iron works best. Let them cook down. Sprinkle only a bit of water if they are about to scorch.

I like them with some heft now, not cooked all day.

My grandmother, like many people from Appalachia, called the meal in the middle of the day, dinner. Sometimes she made sandwiches or hamburgers, but sandwiches weren’t likely in our home. I remember chicken and dumplings, pot roast, or peas and pork chops. Sometimes there were brown beans, vegetable soup, or chili. Fried corn fresh from the garden. Sometimes she placed a salad in the middle of the table in a brown wooden bowl. Occasionally new lettuce and onions wilted with bacon grease. There was always cornbread or rolls. There was always pie. She always set the table. My grandfather always led us in prayer.

My grandfather raised pigs and cured hams that hung from the rafters in the smokehouse. My grandmother was a domestic worker. She cleaned houses for white folks. Before and after she went to work, she fetched water from the well. She slopped the hogs. Canned vegetables and stored them in the cellar. Fed chickens. Milked cows. Shucked corn. Sewed clothes for herself and me. Quilted. But still there were always three meals on the table. Precise. Orderly. Delicious.

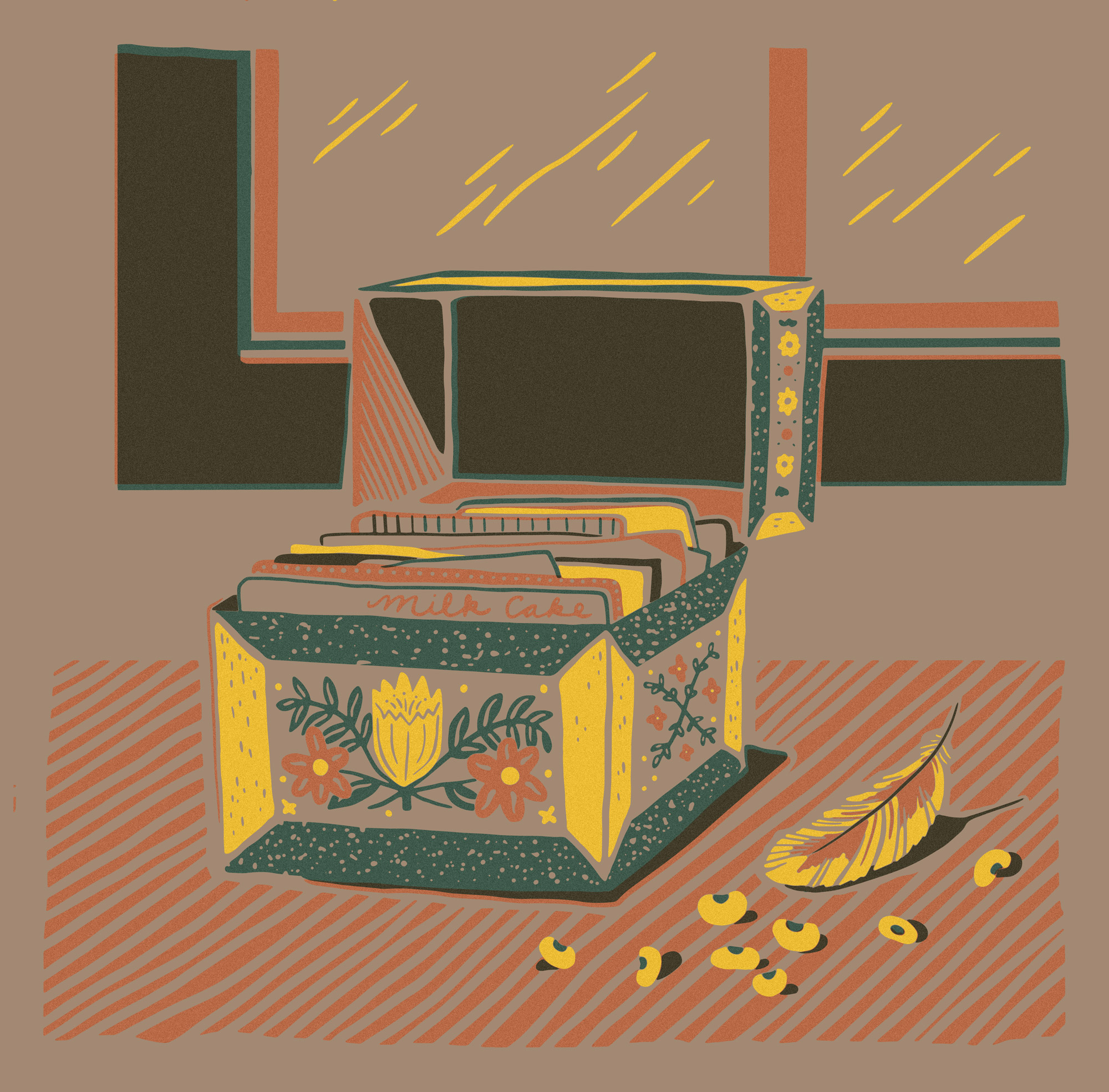

At night, when he’s not working for Toyota, my cousin William is a chef-in-training. Right before Thanksgiving he contacts me on social media and is in need of our grandmother’s jam cake recipe. I send him a photograph of the recipe in her handwriting.

Our grandmother writes in her perfect cursive:

3 sticks of butter, 2 cups flour, 6 eggs, 1 tsp soda, 1 tsp cloves, 1 cup buttermilk, 1 cup raisins, 1 cup pecans, 1 cup peach preserves, 1 cup blackberry jam, 1 tsp cinnamon. Cream butter and sugar well. Add your eggs. Stir soda in buttermilk. Add flour alternately with milk. Flour raisins and nuts (add them last). Add jam and preserves to your butter, sugar, and eggs mixture. Cook two hours in a 350-degree oven.

“On my way to the store,” William says. “I’ll send pictures.”

I still bake her jam cake with caramel icing at Christmas, though no one in my immediate family likes it.

Cinnamon + cloves = childhood.

Every morning of my childhood, my grandmother, who stood a little under five feet tall, donned an apron and cooked breakfast. Slow. Precise. Deliberate.

Supper in my childhood was always on the table by six in the evening. Lamb fries. Frog legs. Fried whiting or catfish. Neck bones. Fried chicken livers or gizzards. Corn pudding. Tall glasses of cold water pulled from the well or sweet iced tea. Biscuits topped with cooked rhubarb, butter, and sugar. After supper, we’d watch TV. Sometimes I ventured out to catch june bugs or lightning bugs in a mason jar. My grandfather nodded in the reclining chair. My grandmother sewed or quilted but always had her eye on something in the oven. Bread. A pie for the preacher or someone who’d lost a loved one. I read a book.

There was always something dead in the kitchen. On occasion a squirrel or rabbit shot and skinned by my grandfather. A bucket of recently caught fish. A chicken with feathers. I remember an entire hog’s head in a galvanized tub, its tongue sticking out. My grandparents hoisted the tub with the hog’s head up on the stove. It covered all four burners. After it cooked all night, my grandmother made souse.

She used a hand-cranked meat grinder to make relish from cucumbers, onions, and green peppers.

By nightfall everything outdoors belonged to nature, but inside we were full and warm and fed.

Last year when I began researching my ancestry for a novel I am writing, I found Aggy, who was my grandmother’s great grandmother. Aggy of Color was born in 1795 into slavery in Virginia. My research indicates she was brought to Kentucky by the Wilkinson family in the early 1800s. She had ten children by Tarlton Wilkinson, who owned her. He is my grandmother’s great grandfather. Aggy remained with Tarlton until he died. As a free woman, she owned land near the place where I grew up. My research ends in 1853 after Tarlton dies. Records documenting her existence vanished, but I imagine her.

I envision her over a large cast iron pot, first in her master’s kitchen and finally in her own. She fed ten children. More than my grandmother’s seven. More than my own three. Did she learn to cook from her mother? Another cook in the heat of the master’s kitchen?

Food rations for Kentucky slaves usually consisted of cornmeal and flour, lard, a bit of fat meat, dried beans or peas, and molasses. If the slave owner allowed it, sometimes the enslaved families grew their own patches of corn, potatoes, turnips, pumpkins, greens, or yellow squash.

From Aggy (3rd great grandmother) to Lizzie (2rd great grandmother) to Lillie (great grandmother) to Christine (grandmother) to Dorsie (mother) to me—we are all the links in this chain.

Patsy Riffe, daughter of Aggy.

Courtesy of the author

After college, when I would return home to the hills, my grandmother would help me settle my three children, then encourage me to climb into my childhood bed and rest while she cooked my favorite foods. I listened to the sounds of her rearranging pots and pans, smelled the aroma throughout the house as she prepared each dish. Sometimes I ventured out to help her and she invited me to sit and talk, but I wasn’t allowed to work. Sometimes she shooed me away and I returned to the bed cozy and nostalgic. Rick James, Prince, and black light posters from my teen years still covered the walls of my bedroom. Sometimes, from the bed, I heard my children laughing through an open window, drunk on the freedom of the farm and the sweets she’d made for them.

Mashed potatoes floating in butter, green beans from the garden swimming in pork fat, chicken fried to crispy perfection, a simple salad with iceberg lettuce, tomato and French dressing. Sweet iced tea in a clear glass decorated with yellow lemons. After I ate the meal, my grandmother brought out my favorite desserts: rice pudding with perfect peaks of toasted meringue or blackberry cobbler with ice cream. A perfect meal for a tired single mother, a lost job, another failed relationship, loneliness.

When my children were young, I cooked a large meal for them every night. Oxtail and sauerkraut; fried chicken. Pancakes and homemade cocoa on weekends. Chili made from the tomatoes my grandmother canned. When I was missing my grandmother, I made pot roast with potatoes and carrots. I fried corn. I hated stewed tomatoes but I made it anyway because she did. Chopped steak with gravy or fried pork chops with new potatoes and shuck beans. For dessert I made strawberry pie or yellow cake with caramel icing. I was a single mother. I worked at Arby’s. I went to college. I cleaned offices at night. I worked as a news assistant at the local newspaper. I worked in public relations. I went to graduate school. I became a professor. I made everything from scratch. My children were grown before I stopped cooking like that. I’ve spent my entire life striving to be a woman worth her salt.

My grandmother never named her cooking method, but I would call it mindful. I’m sure she was thinking of her own mother, her own grandmother, as she prepared our meals. I am not Buddhist, but I’m interested in the practice of mindful eating and cooking. I like this idea of tapping into your emotions before, during, and after cooking. I like thinking about where my ingredients came from. How my grandmother would have prepared the recipe. Who might have grown the vegetables. How much the animal might have suffered. What time the farmer might have gotten up.

My grandmother was married at fourteen. She raised seven children, then she raised me after my mother had a nervous breakdown and was institutionalized. My grandmother attended to my grandfather’s every need, refilling his water cup, bringing him seconds, a plate of cake or cornbread with sorghum. When my twins were little, they were scrawny little girls. She followed them around with a bowl of rice with butter and sugar. “Just take a bite,” she’d plead. She cooked for the church. Big dishes of macaroni and cheese. Large savory hunks of mutton in gravy and mounds of fried chicken. German chocolate cakes. Sweet potatoes. Green beans. She and the other elder women served food out the window of the church dining room for one dollar a plate when the church held basket meetings or revivals. Folks from neighboring churches all around would crowd around her window.

I rarely saw her sit down at any table and eat. She once told me that food didn’t taste as good after she had done all that work. Before a holiday she spent days preparing a meal, but after she served the dinner, she often sat in the corner of the kitchen and ate only a few bites from a small salad plate while everyone else ate in the dining room. Sometimes I would sit with her. I remember the silence. Laughter and talking could be heard from the dining room, but she sat there in her corner savoring her small meal not saying much. I don’t know if she was in meditation or if she was just bone-tired. I wish I’d asked her questions. Sometimes she expressed disappointment. “The rolls didn’t rise right,” she might say; or “too much sage in the dressing.”

As training for mindful eating, I examine a single tangerine. The brilliant shades of orange and green. The small brown indention where the fruit was once attached to the tree. Smell. Run my fingers lightly across the pimply surface. Close my eyes. Breathe. Then peel. Reveal the rind. Bear the fruit. Notice the first squirt of juice and where it lands on my neck and blouse. Section. Masticate. Swallow.

I am always reaching back. Years after our grandmother has died, I call Debra to ask if she remembers the gingerbread sauce. “It had raisins in it,” I say. “It was simple but so good.” Debra calls her mother, Aunt Lo (my grandmother’s daughter-in-law). Our grandparents are dead. Aunt Lo is eighty-nine. Uncle Bub, her husband, is dead. Aunt Lo and Uncle Bub spent the early years of their marriage living with my grandparents. Aunt Lo remembers.

She says:

1 cup of sugar, ¼ cup of butter, 2 cups of water, 1 tablespoon of cornstarch, 2 teaspoons of vanilla. Raisins to taste.

I don’t allow my cousin to tell me how to mix the ingredients. I want the muscle memory in my body to guide me back across the back roads of Kentucky to Indian Creek into the screen door of our grandmother’s kitchen. I can feel it when I catch the right rhythm. I stir. Let the sauce simmer until it is thick. I slice a block of gingerbread into a ceramic bowl. I spoon on the sauce. Taste. Remember.

Lamb fries. Frog legs. Fried whiting or catfish. Neck bones. Fried chicken livers or gizzards. Corn pudding.

A few years ago, I was asked to lead a food presentation in Hindman, Kentucky, at Dumplins and Dancin’, a gathering of farmers, dancers, chefs, and food activists committed to the preservation of Appalachian foodways and music traditions. I was asked to demonstrate (Food Network–style) my grandmother’s chicken and dumplings. As a writer my first inclination was to just write something and read it. But mountain people are stubborn. They insisted. Nervous, I came armed with history.

I hang a dress my grandmother had sewn and wore on the door of the kitchen. I place her photograph on the prep station, and I begin. I heft the heavy stock pot, add chicken, water, and salt. My grandmother used pieces cut from a whole chicken. I just use the breast. While the chicken is boiling, I make dumplings. Two cups of self-rising flour, a half cup shortening, one cup of milk. I cut the shortening into the flour, add the buttermilk. Sprinkle flour on the table. Roll out the dough, then cut the dough in one-and-a-half-inch squares with a knife. The steam in the hot pot rushes across my face. Once the chicken is done, I reduce the broth. I let the chicken cool, shred it into bite-sized chunks. Add the dough squares to the boiling stock. Reduce the heat and let it thicken. Add the chicken. The pieces of tender meat float in the bowl with swirls of yellow fat and fluffy dumplings. I serve the dish with a pone of cornbread. I smile at my grandmother’s photograph. See her as a kitchen ghost. Thank her for being there.

Last month while my cousin Darlene was babysitting her grandchildren for the week in Lexington, she calls me and asks where she can buy fresh vegetables. I point her in the direction of every farmers market I know. And of course this leads us into a discussion of our heritage. “You’re doing it,” I say. “Like Granny and Aunt Lo did.”

“I need to get back home and tend it,” she says proudly of her garden. “Need to do my canning.”

She tells me that along with the vegetables she cans chicken.

“Chicken?” I say. “In mason jars?”

I don’t remember our grandmother canning meat, but we are the kitchen ghosts of the future, morphing, changing the way things are done. Darlene is not satisfied with the produce she finds in the city. Not the prices. Not the quality. We talk about the value of a vine-ripened tomato from down home. A little bit of jealousy rises up in me when she talks about her garden. Simple. Ancient rituals in the path of our ancestors’ footsteps. She hoes and bends and weeds and harvests. She serves her own food on the table. She is innovative and lively in her kitchen, looking for ways to blend our old ways with the new.

Years ago, when I left my grandmother’s house, she filled my car with rations: Jars of bright red canned tomatoes for soup. Paper sacks of dried apples for making fried pies. Recipes. Whole cakes. Jars of relish and green beans.

A jar of green beans she canned still sits on my counter. I refuse to use it because it is the last one she gifted me before she died. I rearrange the mason jar on the counter so that it is in my line of sight while I cook. I have some of my grandmother’s pans and serving dishes. Cooking for me is part anxiety, part meditation. I invite each kitchen ghost in with open arms. I take up the knife. They watch. I take up the spoon and the knife. I slice. I pour. I begin.

My grandmother nursed my fevers, kissed my bruises, encouraged my dreams. She filled first her pots and then our bellies in the same way that her mother and grandmothers had for generations. Through slavery. Through manumission. Through the Great Depression. Through wars. Through poverty. Through segregation. Through the Civil Rights Movement. Through racism. Women of this ilk always find a way.

I want the muscle memory in my body to guide me back across the back roads of Kentucky to Indian Creek into the screen door of our grandmother’s kitchen.

At my house I have my go-to stash of recipes memorized. When we eat vegetarian I make a mean baked tofu that my husband Ron swears tastes like fried fish. When we were on our way to becoming vegan, I developed a recipe for vegetarian breakfast sausage that I prepped each Sunday for the following week. When we are carnivores (as we are currently), one of my specialties is meatloaf, mashed potatoes, and fresh collard greens sautéed in garlic. It’s rare that I cook anything experimental or extraordinary, but I do have a few “invented” dishes that I’ve been cooking for twenty years. My adult children refer to them as the corn and cream stuff or the rice and tomato and beef thing. And of course there are the classics.

Even after twelve years of bliss, after every meal I cook I always ask my partner, “How was it?” Was it good for you? If my husband says he doesn’t like the meal or is nonchalant about it, tears well up in my eyes. Sometimes I become angry. “Baby, it was fine,” he says, when he sees me grow sullen. But is it just fine? My grandmother didn’t teach me how to cook so that my meals would garner such a lackluster response. Women from this family know how to burn.

You put your foot in it!

I’ve died and gone to heaven!

I’m foundered!

All appropriate responses that my city man knows nothing about.

Even if he closed his eyes and rolled his head back in satisfaction or a gravelly moan escaped from his lips, that would satiate me. Something that confirms: Yes, there is a god, and god touched the woman who made this food!

When I call Debra, we talk about the photographs that my cousin William posts on his Facebook page of the meals he’s learning to prepare in culinary school. We make ourselves hungry just talking about them and laugh. We talk about each other’s children, work, and the extended family. Our conversation is populated with laughter and nostalgia and love. She tells me what she is cooking for supper.

I tell Debra about the hot milk cake.

“I don’t think Granny made that,” she says.

“I think it was Aunt Edith Patton who gave me the recipe,” I say. “Remember her?”

We talk about Great-Aunt Edith’s long white hair. Her walk. Her face. I tell her about the venison I ate at Aunt Edith’s table once.

“I never heard of hot milk cake,” Debra says.

I marvel at its simplicity.

“It’s delicious,” I say. “Do you remember that peach upside-down cake Aunt Lo use to make?”

I think of Ma Aggy held in captivity as a slave when I make the cake. It’s something she could have made by combining her own rations with a few items taken from the plantation kitchen.

½ cup butter, 1 cup milk, 2 teaspoons vanilla, 4 eggs, 2 cups of sugar, 2 cups of flour, 2 teaspoons of baking powder, 1 teaspoon salt

Melt butter in a pan then stir in a cup of milk, heating until bubbles form. In a bowl beat eggs and sugar until they triple in size. Alternate dry ingredients with the wet. Pour in a greased skillet. Bake at 325 degrees until a broom straw comes out clean.

I know that women in my family have been kitchen ghosts for centuries.

Two weeks ago when we invited friends over for couples night, my partner cooked his famous fried cabbage. Cabbage, onions, a generous amount of butter, and smoked sausage. I can’t recall my grandfather ever cooking a meal, but Ron has his specialty and often cooks breakfast in our house. He washes all the dishes.

I talk to our friends while he cuts the cabbage and assembles the other ingredients in the skillet. In our twelve years together, I have grown toward an understanding of shared responsibility and welcome him into what was previously my domain.

Suddenly the smell of cabbage cooking blossoms inside me a need for cornbread. I recognize the memory easily as soon as it wells up. I spring up from the couch, and my partner and I move around each other in the kitchen like we were dancing. Slow. Methodical. A meditation. We have a rhythm between us. I mix the eggs and milk. Add the cornmeal and pour it into a hot skillet. I make the cornbread. We eat in silence, our forks tink gently against the plates.

One hot night in Florida while on a writing fellowship, I woke up crying with Ma Aggy’s voice coming through me loud and clear. Though she has been gone for more than 250 years, I could hear her voice—urgent and persistent. I headed to my writing desk and wrote of her life in 1808 as a Kentucky slave.

We slept in the corner of the kitchen. The kitchen smelled of fried meat, copper, and salt, and in the corner where we slept the air was so humid I felt nauseous. In the wee hours of the morning, before the plantation stirred, I lay half asleep swiping at gnats swarming at the corners of my eyes and sweating through my dress. It was in those minutes between sleep and wake that I heard my mother singing my name, though she wasn’t calling to me in your language. The sound of her voice floated into the window like a feather and then took wing like a bird and flew in a circle around my head before it disappeared up toward the rafters while I lay there in the dark.

We take the buckets and draw water from the well. We empty the slop jars. We gather eggs from the hen house and a bit of jowl from the smokehouse. We render fat for the biscuits and for the soap. We gather stored ashes and make lye soap. We sew Missus a dress but she wants one more fine, so we give a knapsack to David to take down to the Bowman’s place for Sally to fix. We draw more water from the well and build a fire in the backyard for washing. We boil the clothes in lye soap. Hang the clothes on the line. We cook the hog and the corn. We fold the clothes. We pick vegetables from the garden. We pick worms off the tobacco before Marse Bowman sends his field hands to help. We milk the cows. We churn the butter. We feed the chickens. We slop the hogs. Up in the night we pick a mess of beans from our little garden, fry up some hoecakes from our own rations, and eat a little bit for ourselves. We share our food.

We share our food.

I know that women in my family have been kitchen ghosts for centuries. Peeping over the shoulders of our daughters and granddaughters and sons and grandsons. Saying:

Just a little bit more.

Turn your fire down.

Not too much salt.

Please have some, we have plenty.

And I imagine myself many years from now, standing in my great grandchildren’s kitchen, nodding my head as they work, whispering in their ears, “That’s right. Keep it up. We will always have plenty.”