Potato Travelogue

A month-long journey into the flavors and traditions of Peru’s favorite food

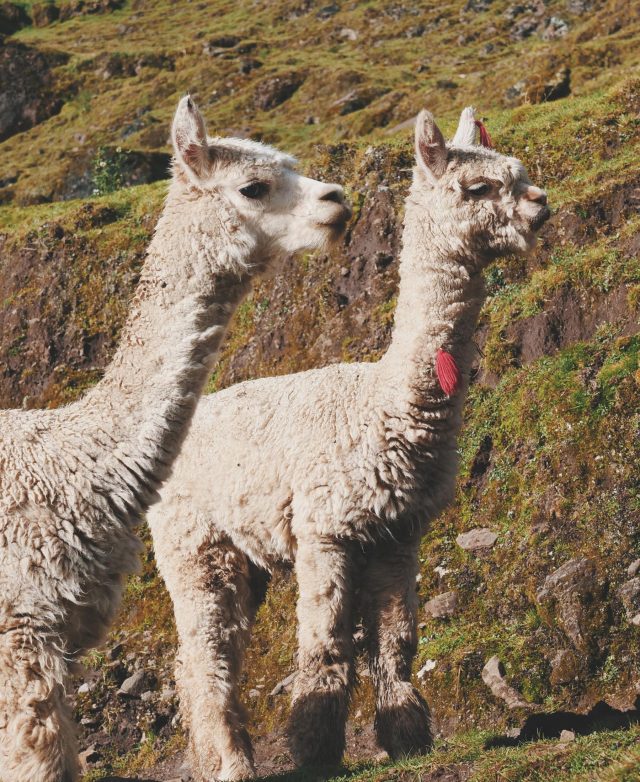

PapasNativas

Approximately 8,000 years ago, the first wild potatoes were harvested from the high-altitude soils surrounding Lake Titicaca at the foot of the Andes Mountains. Since then, more than 4,000 varieties of native potatoes—known in Peru as papas nativas—have been cultivated in the Andean highlands. On a month-long journey through Peru, we encounter the diverse flavors, cultural significance, agricultural challenges, history, and daily uses of papas nativas.

Laguna Willkaqucha

The Andes mountain range is the western “backbone” of South America. Stretching from Venezuela in the north to Chile and Argentina in the south, it reaches heights of nearly 23,000 feet above sea level. We begin at 10,000 feet in the town of Huaraz, nestled in the Callejón de Huaylas valley in the north-central highlands of Peru. We set out along a steep road, past adobe homes and small farms, struggling to catch our breath in the thin air. After several slow hours under a strong sun, we reach Laguna Willkaqucha, or Lake Wilcacocha. In Quechua—the primary language of the Inca Empire, still spoken by eight million people in the Andean highlands—willka means both “grandchild” and “sacred.”

Here at 12,000 feet, with Peru’s highest mountains towering above the horizon, we have arrived at the native habitat of papas nativas.

Adapting to the Andes

For thousands of years, Andean communities have adapted to harsh high-altitude conditions: low oxygen, frigid temperatures, strong sun, and astonishingly steep grades of land. The same is true for Peru’s native potatoes. Where most crops cannot survive the stark climate, papas nativas thrive at heights ranging from 11,000 to 14,000 feet. Thus, through many civilizations, it has been the potato that has provided critical sustenance and nutrition to the people of the Andean highlands.

French Fries from the Andes

At the end of a long day—sunburned, sore, and suffering from mild altitude sickness—we find the closest restaurant to our guesthouse and, though they don’t serve papas nativas specifically, we devour our first Peruvian potato meal: greasy french fries served with chicken, smothered in hot green chili sauce. Though it satisfies our hunger, it neither feels healthy nor tastes all that different from potatoes we’ve eaten in other places around the world.

Chahuaytire

From Lake Wilcacocha, we head south to Willka Qhichwa, the Sacred Valley, where we visit the six Indigenous Quechua farming communities that make up Parque de la Papa, or Potato Park. Here, farmers known as “potato guardians” grow 1,300 varieties of papas nativas across 15,000 acres of sustainable farmland. Collectively, these communities are combining deeply rooted traditional knowledge with science in order to preserve the agricultural diversity and cultural traditions that have sustained them for centuries.

The first potato was domesticated by early Andean people around 8,000 years ago. The tradition of careful and patient cultivation of the plant is visible in the work of the Quechua farmers across the Parque de la Papa in the way they select for size, taste, and different climates. Today, there are thousands of varieties of papas nativas that differ in shape, color, texture, and nutritional value.

In the village of Chahuaytire, we meet farmers Ernesto and Martina. They are cultivating sixty varieties of papas nativas on their land, which feed their family year-round and are honored as an ancestral heritage.

Health and Nutrition

Over many generations of cultivation, papas nativas reached a high level of nutrition. Almost all varieties are a good source of starch, vitamin C, and calcium. Others are high in protein, vitamin K, or phosphorous. The potatoes that Ernesto and Martina grow organically, without any agrochemicals, have far more vitamins and amino acids than the common white potatoes we find at home in the Netherlands.

Papas nativas also have many uses beyond cooking. Ernesto and Martina use them for their health benefits, applying or ingesting the juice of the potatoes to treat skin rashes, kidney stones, or headaches. Papas nativas are believed to offer a wide range of other medicinal benefits, with different varieties containing properties that are known to boost the immune system, prevent cancer, aid in the treatment of osteoporosis, and more.

Ernesto & Martina

Standing in one of his potato fields, Ernesto describes the different varieties of papas nativas that he grows for his family.

“Papas nativas have applications for everything; that’s why we can’t lose them. We need to keep them around.”

Taste and Texture

Ernesto and Martina invite us to share a meal with their family. Alongside a healthy slab of goat cheese, they serve two varieties of papas nativas. One looks similar to the potatoes we eat at home but tastes far richer and more complex. The other, cooked in a pot atop a bed of straw, is small with coarse skin, a bitter taste, and dry texture. Martina tells us this is the chuño—the river potato.

Chuños

The chuño, also called tunta or moraya, is a type of papa nativa that has been dehydrated through a process that dates back to the Tiahuanaco culture, which flourished near lake Titicaca around 800 CE. The same process is used today: Once the papas are harvested—usually in June and July—a farmer selects some of the smaller potatoes to be made into chuños, which can either be black or white in color, depending on which dehydration process is used. Black chuños are made by leaving the potatoes out in the freezing Andean air overnight. They are then crushed to remove any liquids. If a farmer wants the chuños to be white, she will soak them in a mountain stream and then sun-dry them. Whatever the color, the chuños are essentially freeze-dried and can be stored for up to a decade.

Amaru

We continue to the nearby village of Amaru, where we hope to find the man called Técnico de Andes, the “Technician of the Andes.” After his son calls him down from the fog, we meet Adrian Cipatakuri—an expert on the ecosystems and climates of the Andes. He invites us into his greenhouse where he has conserved 770 varieties of papa nativa seeds, protecting them—as well as any seed bank would—from disease, worms, contamination, and frost. His successful cultivation and careful preservation of papas nativas relies not just on scientific knowledge, he says, but on spiritual knowledge as well: the phase of the moon, the mountain spirits, and signals from the ancestors.

A Limited Crop

Growers of papas nativas are almost entirely subsistence farmers, growing only what’s needed to feed their own family. For most of them, it is not practical to produce these crops at a larger scale: this is, in part, because it is so labor-intensive to forego commercial pesticides and fertilizers; but there is also little demand for these native potatoes, even within Peru.

“We work with Pachamama and the Apus (mountain spirits). We also look for certain flowers and listen for the cry of certain animals. That’s how we know when to plant the potatoes.”

Adrian Cipatakuri

Adrian Cipatakuri discusses the diversity of papas nativas as an ancestral heritage and his process of saving seeds in his greenhouse.

More Than a Beautiful Flower

The potato fields that we encounter in Chahuaytire and Amaru are a sea of purple, white, and pink flowers. Each color—and the varying shades of that color—indicate different varieties of papas nativas growing belowground.

The potato, Solanum tuberosom, is an herbaceous annual: it sprouts, flowers, produces tubers, and dies in a single growing season. The ambolocoto, or stamen, of the flower carries the seeds of the plant, which enable it to reproduce through pollination, but farmers reproduce the next year’s crop of potatoes vegetatively—planting tubers from last year’s harvest.

Potatoes and Rice

As we travel by bus across the country, we eat at many roadside family restaurants. Potatoes are on the menu at all of them. The food is tasty and plentiful and there’s no risk of going hungry. Soup is served first with a side of potatoes, followed by the main course, also served with a side of potatoes, and often rice. While modern diet fads may discourage so many carbs, from the Peruvian perspective, the potato is a nutritious staple.

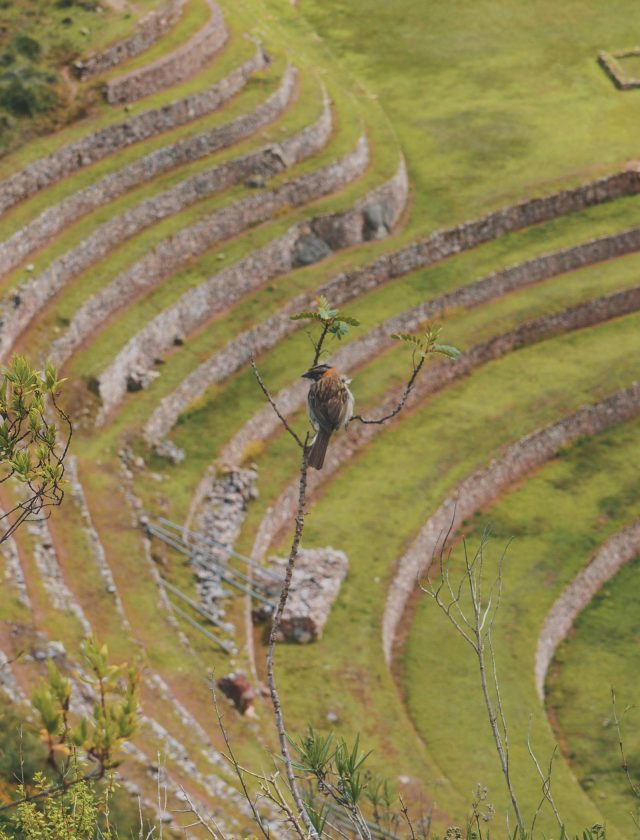

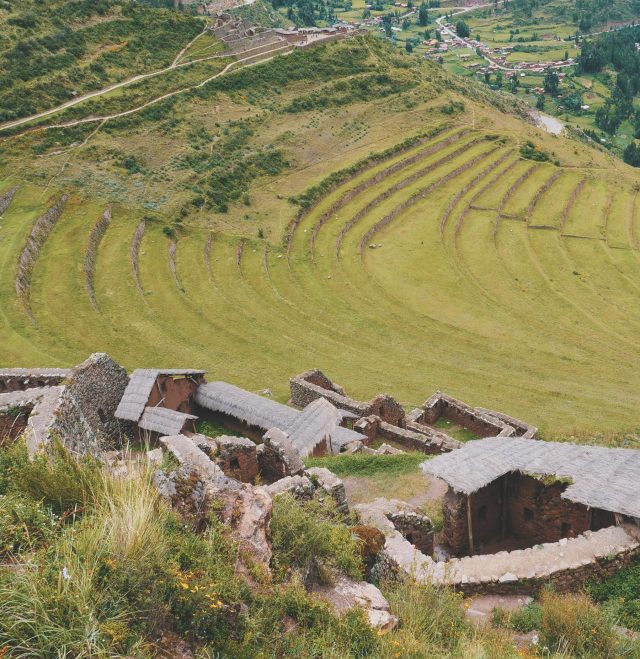

Moray

Cultivating papas nativas is part of an ancient agricultural practice that dates back to the Inca and pre-Inca people who worshipped Pachamama, or Mother Earth.

On February 22, we arrive at Moray, an ancient agricultural laboratory built by the Incas in the Sacred Valley. Seated at 11,090 feet, Moray is a series of enormous circular stone terraces with different soils at every level. These soils are believed to have been imported from different parts of the Andean region. Studies suggest that the Inca observed the crops planted in each terrace, helping them determine which varieties were best suited for the varying climates across their civilization.

In Moray, we see an ancient understanding of the land and climate that is still present in Andean communities today. Thousands of varieties of papas nativas are a testament to the continuing success of traditional, localized knowledge.

Because of differences in depth, orientation toward the sun, and wind patterns, the temperatures can vary up to 60 degrees Fahrenheit between the top and the bottom terrace, creating a unique microclimate for each circular layer of soil.

Potatoes on Top

In the evening, we indulge in street food from the local carts and stalls: salchipapas (sausage and french fries), papas rellenas (fried stuffed potatoes), and anticuchos (grilled beef heart) with a boiled potato on top. Despite the food being delicious, we learn that none of the vendors cook with papas nativas: almost all of them use Canchán, Yungay, Andina, Perricholi, or Única—the most common potatoes grown in Peru, often grown with chemical fertilizers and adapted to be mass-produced at the expense of crop diversity and nutrition.

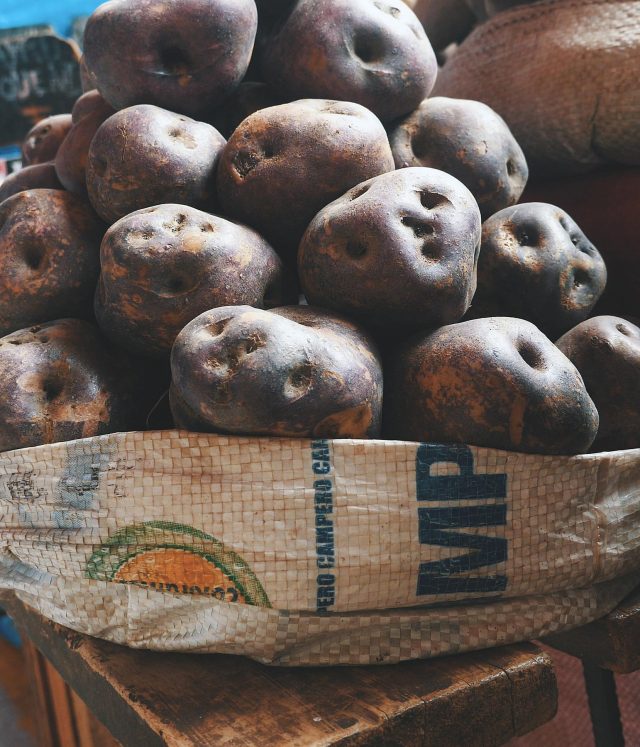

Mercado San Camilo

From the Sacred Valley, we take a bus further south to Arequipa, Peru’s second-largest city. Encircled by three volcanoes, Arequipa is known as La Ciudad Blanca, The White City, as many of the structures are built from sillar, a white volcanic stone. Venturing through the city streets, we encounter potatoes on every street corner, in food stalls, and on the backs of trucks. Here too, most of the potatoes we see are not papas nativas. At a large market in the heart of the city, only a few stands sell native potatoes, highlighting their scarcity in mainstream markets.

4000 Varieties

Different communities across the Andes have different preferences for the varieties of papas nativas that they cultivate, based on local history, social values, and climate. Though most of the potatoes never make it to any market, they are traded between highland and lowland communities, given as gifts for weddings and other special occasions, and, of course, eaten throughout the year by the families who grow them.

“Ser mas Peruana que la papa.”

“Be more Peruvian than the potato.”

Peruvian Pride

As the story goes, when the ancient Andean people first encountered potatoes growing in the ground 8,000 years ago, they took them to be gifts from the gods. Archaeological studies show that the Incas later came to worship Acsumama (acsu for potato, mama for mother). Potatoes continue to hold a central place in both the Peruvian diet and mainstream culture: “Be more Peruvian than the potato” is a common saying, restaurants advertise themselves through the quality of their potato dishes, and images of potatoes line the streets.

Restaurante Hatunpa

The average Peruvian eats potatoes for breakfast, lunch, and dinner and consumes around 330 pounds of potatoes per year. May 30 is celebrated as National Potato Day, and many other smaller festivals throughout the year honor this crop.

While papas nativas remain a dietary staple among many Andean communities, they account for a very small percentage of Peru’s national potato consumption, despite their renowned nutrition and flavor. But we also meet a few people in the city—like the chef at Hatunpa, a restaurant in Arequipa—who are trying to reintroduce papas nativas to mainstream food culture. At Hatunpa, papas nativas are the central ingredient on the menu.

Cecilia Guerra

Cecilia Guerra, the chef at Hatunpa, speaks about the myths, history, and present-day significance of the potato in Peruvian cuisine.

Preparing Papas Nativas

Regular potatoes are often fried, mashed, mixed, stuffed, baked, and dressed with sauces and cheese. Papas nativas, on the other hand, are most often simply boiled or steamed in their skin, enabling them to retain their nutrition and natural flavor. There’s great pride in the fact that they need only a bit of boiling water to be delicious and healthy. Consistent with this tradition, the papas nativas at Hatunpa are cooked and presented with an ethic of simplicity.

Dulce de chuño

Papas nativas are not only used for savory dishes. A popular dessert is dulce de chuño—a freeze-dried potato served like a sweet porridge with cinnamon, anise, cloves, and sugar.

CIP

Having sampled papas across Peru, we arrive at our final destination of the trip: Centro Internacional de la Papa (CIP) in Lima. This organization promotes international food security and sovereignty through root and tuber agricultural systems, housing a collection of 4,354 native, and cultivated potato varieties from seventeen countries. Their gene bank includes specimens from about 3,000 potato clones of breeding research 7,000 potato varieties.

CIP works with farmers and seed savers like Ernesto, Martina, and Adrian in Peru and other Latin American countries to collect seeds and tubers of different varieties of papas nativas. In a process called repatriation, CIP then cleans the tubers of viruses and returns them to the farmers, who plant them and monitor their growth and adaptability. Together, Indigenous farmers and scientists are working to ensure the sustained diversity of papas nativas, especially as the climate of the Andes is rapidly changing.

International Potato Center

Ana Panta, a scientist at CIP, tells us about the importance of preserving the genetic diversity of papas nativas in a time of ecological crisis.

Seed Sharing

More than one billion people worldwide rely on potatoes as part of their diet. But like any industrialized crop, monocrop potatoes have lost much of their original nutrition and are susceptible to blight.

CIP has scientifically documented the high nutritional value and wide adaptability of papas nativas, and this research has confirmed their belief that native tubers constitute a reliable and sustainable source of sustenance, especially in communities that are more likely to face food scarcity. Through the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture, CIP distributes potato seeds internationally—particularly to farmers in developing countries—offering varieties that are healthy, disease-resistant, and able to withstand harsh climate conditions.

With Andean farmers carrying on the ancient practice of planting papas nativas in their native landscape, and a growing number of small-scale farmers around the world planting them in new soils of diverse climates and communities, the unique heritage of this Peruvian crop continues its 8,000-year journey.

Peruanita, Tuqra Papa, Yuraq, Puka Chunya, Witqi Suytu, Ajo Suytu, Suytu Oca