Camille T. Dungy is the author of four collections of poetry: Trophic Cascade, Smith Blue, Suck on the Marrow, and What to Eat, What to Drink, What to Leave for Poison. Her debut collection of personal essays is Guidebook to Relative Strangers. Camille edited Black Nature: Four Centuries of African American Nature Poetry. Her honors include an American Book Award, two Northern California Book Awards, two NAACP Image Award nominations, a California Book Award silver medal, and she was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2019. She is a professor in the English Department at Colorado State University and the poetry editor at Orion Magazine.

Studio Airport is Bram Broerse and Maurits Wouters. Together with a small team of creatives, they run a design practice based in Utrecht, the Netherlands. The studio has been recognized with national and international awards, including the Agency of the Year Award and Best of Show at the 2024 European Design Awards. Past projects include Hart Island Project (New York), Amsterdam Art Council, and Greenpeace International.

Rejecting the refrain “there are no words,” Camille T. Dungy reaches for a language to encompass the experience of loss, extinction, and loneliness.

What we need are tear leaders, not cheer leaders.

We need tear leaders to teach us how to mourn.

—Allison Adelle Hedge Coke

I think of my friend’s mother, dying forty years before she imagined she was due to die. We stayed in a spacious house in the Oregon countryside, rented by my friend so there would be room for her mother’s small herd of visiting stepchildren, relations, friends. In those days, my friend was hardly ever alone with her disappearing mother.

A group of us deliberated around the dining table. These were the days of the Occupy movement, when activists renamed Frank H. Ogawa Plaza in Oakland—who remembers what that was about?—calling it Oscar Grant Plaza instead. It was necessary, some of us believed, to highlight everyday—modern-day—catastrophe: the unjust death of yet another young black man. Others believed that erasing a survivor of US internment camps from our collective memory might, in the end, do more harm than good. What was the use of having an immediately accessible reference like Oscar Grant if we didn’t acknowledge this country’s long history of marginalizing and jeopardizing particular lives? Was it violence upon violence to memorialize Grant while disappearing Ogawa? And what will happen when we forget the history attached to Grant’s name, too?

I don’t remember if there was a satisfactory conclusion to this debate. I do remember that I’d taken charge of cooking part of our lunch. I used a recollected pasta recipe that promised a delicious and easy meal for six to eight, but the red sauce I served proved bland and watery; the noodles, a mush.

Possibly, no one else much remembers the quality of that afternoon’s meal, though it is a culinary failure that still nags me nearly a decade after the fact. Has such a thing ever happened to you? It had been my ambition to share a perfect bowl of pasta with the table, but it wasn’t perfect, and folks said that it didn’t matter, and I still can’t let it go.

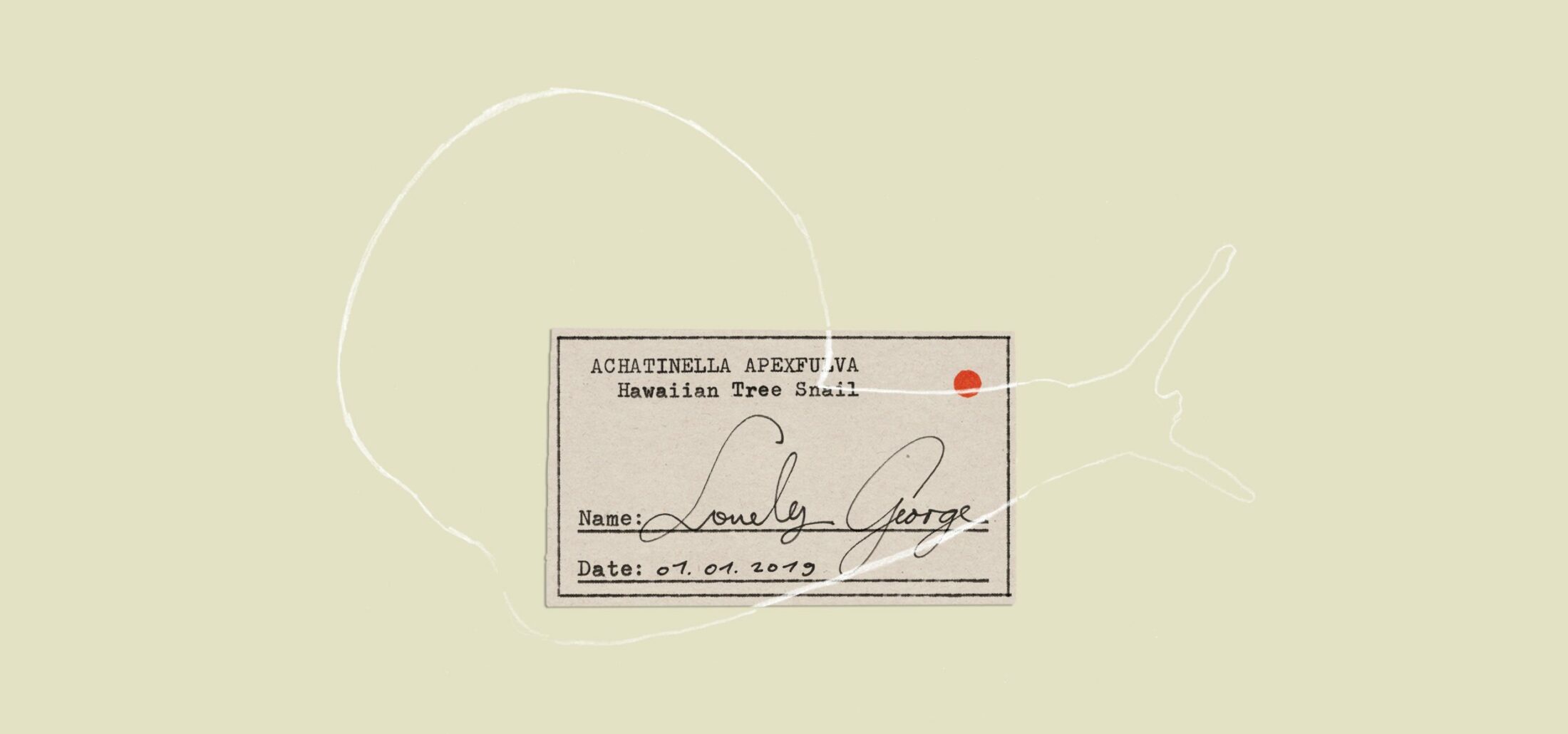

Lonely George died on New Year’s Day 2019. He was a Hawai‘ian tree snail.

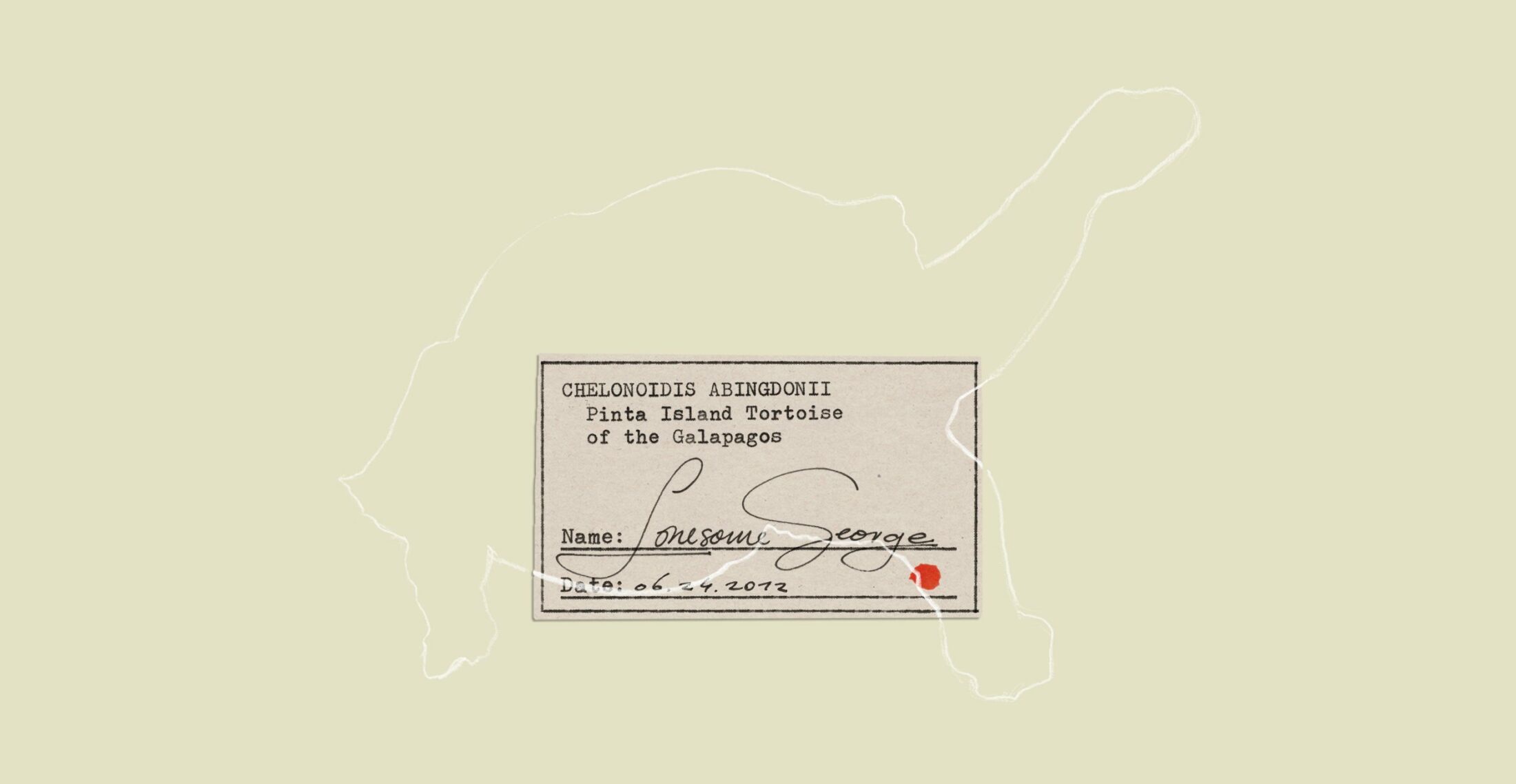

His name echoes that of Lonesome George, the Pinta Island tortoise of the Galápagos Islands who died in 2012. Like Lonesome George the tortoise, Lonely George the tree snail had no one with whom to mate. These tree snails can live more than twenty years in the wild. Lonely George, part of a captive-breeding program, survived for fourteen years. He had outlived the rest of his kind by nearly the entire measure of his solitary life.

Unlike Lonesome George, Lonely George wasn’t really the last male of his species. These snails are hermaphrodites. The last Achatinella apexfulva was neither completely a he nor solely a she. But we don’t have much of a way in our language to name gender fluidity. To accommodate our bias toward gender binaries, even among species for whom such binaries are misleading and perhaps patently untrue, the last representative of what was the first species of Hawai‘ian tree snail described by Western science—thanks to shells in a lei presented to Captain George Dixon in 1787—we call Lonely George.

I remember how heated our conversations became in the big house that weekend. As if our futures depended on everything we discussed, even when the conversation drifted to matters of little value. We argued about where in New York City you could find the best bagels, naming specific delis and bakeries and arguing over the relative chewiness of one’s bread or the creaminess of another’s schmear, until Carolyn—that is the dead woman’s name—silenced us.

She would never eat a New York bagel, she said. She spoke in the matter-of-fact way a docent might name the pattern on a set of everyday dishes. She said, “There are so many things I’ll never have a chance to taste.”

I shipped an express order of bagels and toppings to the house in the country later that week, after I returned home. By that time, Carolyn was hardly eating. I doubt she had a chance to enjoy any of it.

In the condolence card I sent my friend, I may have used a phrase I was taken with at the time: “There are no words.” I used to write this when someone I loved had lost someone they loved, because it made a sort of sense.

I don’t perceive this statement as consolation any longer.

There are words—about pain and the deepest kinds of sadness, about being orphaned and lonely and feeling bereft. There are words—about the inability to hold and, by that holding, to sustain another heart. There are words—and they matter—about the erasure of one particular light, of one particular life, and, with that life, all the lives that link with it, all the darkened histories that light—that life—once revealed.

These are difficult words to reach for in my language.

There is no way to describe what it means to acknowledge the erasure of a life.

We are likely doing the Achatinella apexfulva a disservice—even as we work to honor the memory of the species—by giving the last of its kind such an incomplete name. Maybe when we say, “There are no words,” we mean there is no way to describe what it means to acknowledge the erasure of a life around which so much language might have been created.

“George,” we say, because we have little room in our language to name a being who is neither he nor she but is something larger.

Apexfulva, the latter of George’s binomial names, speaks to the yellow tip of the snail’s shell, the coloration pattern that made the species attractive to collectors. In the days before the arrival of Europeans, George’s kind looked good in leis made for people of high standing. In later years, George’s kind looked good on souvenirs.

The name “George” speaks of the first white man to hold such a creature. Or, truly, to hold the shell from which the living creature had disappeared.

The name “Lonely George” speaks of another shelled being, one who was already lost before many of us found him. It was solitude and peril, their status as the last hope for their species, that made these lone survivors recognizable enough—and, therefore, important enough—to earn these English names.

Oh, but why are the names we use to recognize another so often harbingers of death? Lonely George. Lonesome George. Before their near eradication, and then eradication, the Achatinella apexfulva and the Chelonoidis abingdonii were set apart—for us—by their binomial nomenclature as well as by the functional descriptions (“Hawai‘ian native land snail” or “Pinta Island tortoise”) that mark their existence as life forms separate from us. Only when we’d almost lost the last did we bestow on them the familiar name “George.”

Pūpū kuahiwi (mountain shell), kāhuli (land shells), kani ka nahele (“the sound of the forest”), pūpū kani oe (a phrase I’ve seen translated as “shell that sounds long,” which speaks to the whistling sound of the snails): these are some of the Hawai‘ian names for members of the family Achatinellidae. Lonely, we say now, because though the forests of Oahu once resounded with the songs of tens of thousands of snails, all we have left are the rattles of empty shells.

I’m not at home as I write this. My family and I have been living, since the new year, in another state. The weather is different here, and we don’t know how to describe it. “It’s cold,” we tell our friends back home. When they ask for a number and we tell them a number, they sound confused. The numbers on the thermometer don’t seem to register the truth as we feel it.

I’m not sure if it’s the cold-trapping dampness of this region that keeps us shivering or that we’re acutely aware of all the familiar things that no longer surround us.

We are lonely. It has taken me nearly a month to put words to the feeling, but that is it. We are lonely. We are raw and alert.

The wind sounds different in this new house. The trees don’t look the same.

In the big house in the country, sometimes, my friend once told me—even with all those people around, and even though she knew that on the grand scale of existence, the cause of her suffering was part of the natural order—she would go into her room to be by herself and cry because of the magnitude of all she was aware she was losing: everything, everyone, for which there is not enough time.

Sometimes this is what it looks like to be lonely.

As was also true for Lonesome George, the eradication of all of Lonely George’s eligible mating partners and, with them, the potential for the continuity of a species is largely the fault of human beings. We can also lay blame on the rats we carry with us. Ships that brought the attention of Western science to the Achatinella apexfulva—the yellow-tipped tree snails of Oahu—also brought rats, who like to eat snails. When we say “rat” and mean one who betrays us, it is perhaps with stories like this in mind.

Agricultural practices that relied on goats, cattle, and pigs disrupted native ecosystems on Oahu. We can also name logging as a culprit. And plantation-based pineapple production. And the housing and resort developments that require landscaping that is not the landscape native to the island that creatures like Lonely George evolved to survive. We can name rats, goats, cattle, landscaping, pigs, but we humans are the common denominator.

In 1936 some person brought a few giant African tree snails to Hawai‘i because they wanted tasty snacks for humans and livestock. Giant African tree snails are among the largest snails in the world. As a result of their size, they consume great quantities of Hawai‘i’s lush island foliage, threatening native and agricultural vegetation alike. In a bid to control this voracious threat, in 1955 a new set of people introduced the carnivorous rosy wolfsnail (Euglandina rosea) to the islands. The outcome did not turn out as they intended. Is the outcome ever as intended in stories such as this?

The rosy wolfsnail has done relatively little to reduce the population of giant African tree snails, preferring to devour members of the eleven families of native snails that once existed on the Hawai‘ian Islands in abundance. “The extinctions have just been horrendous,” University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Professor Emeritus Michael Hadfield told CNN in a story about the death of Lonely George.

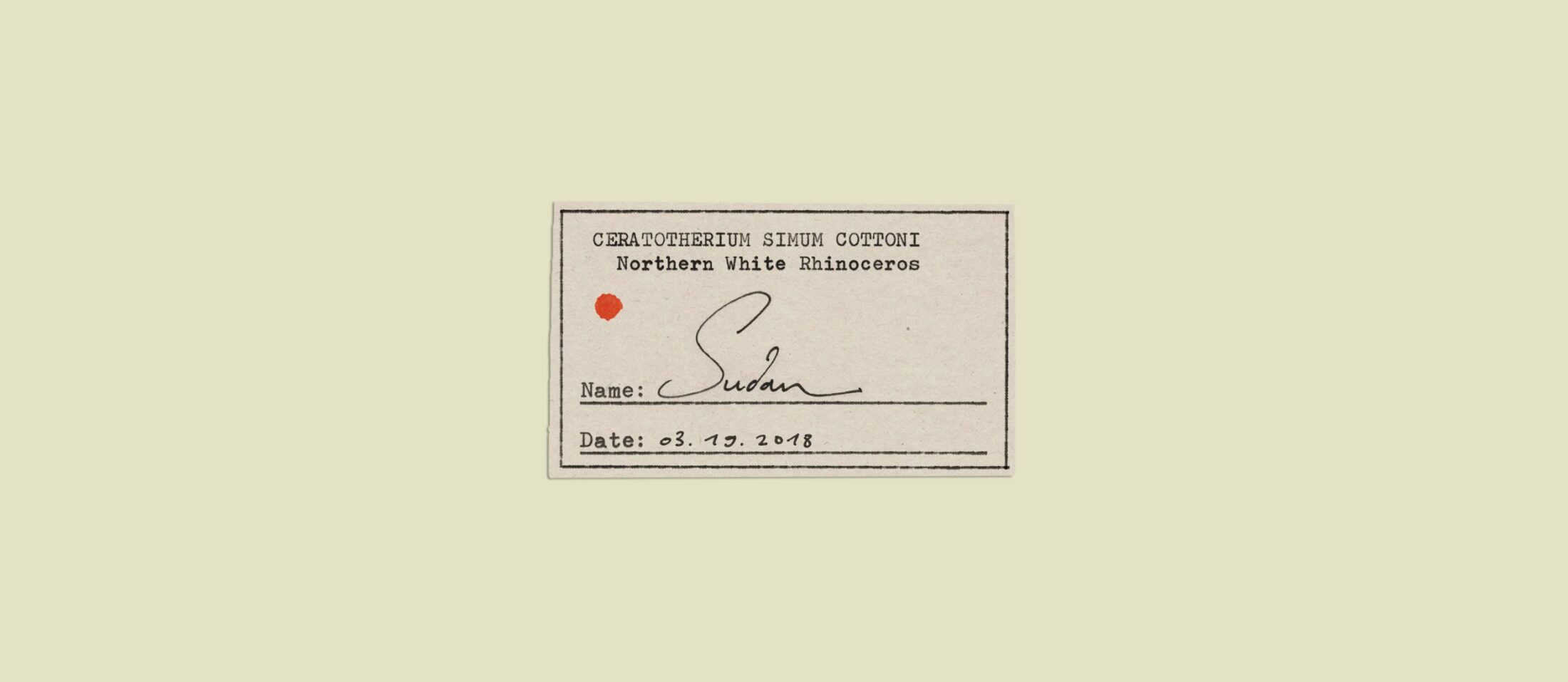

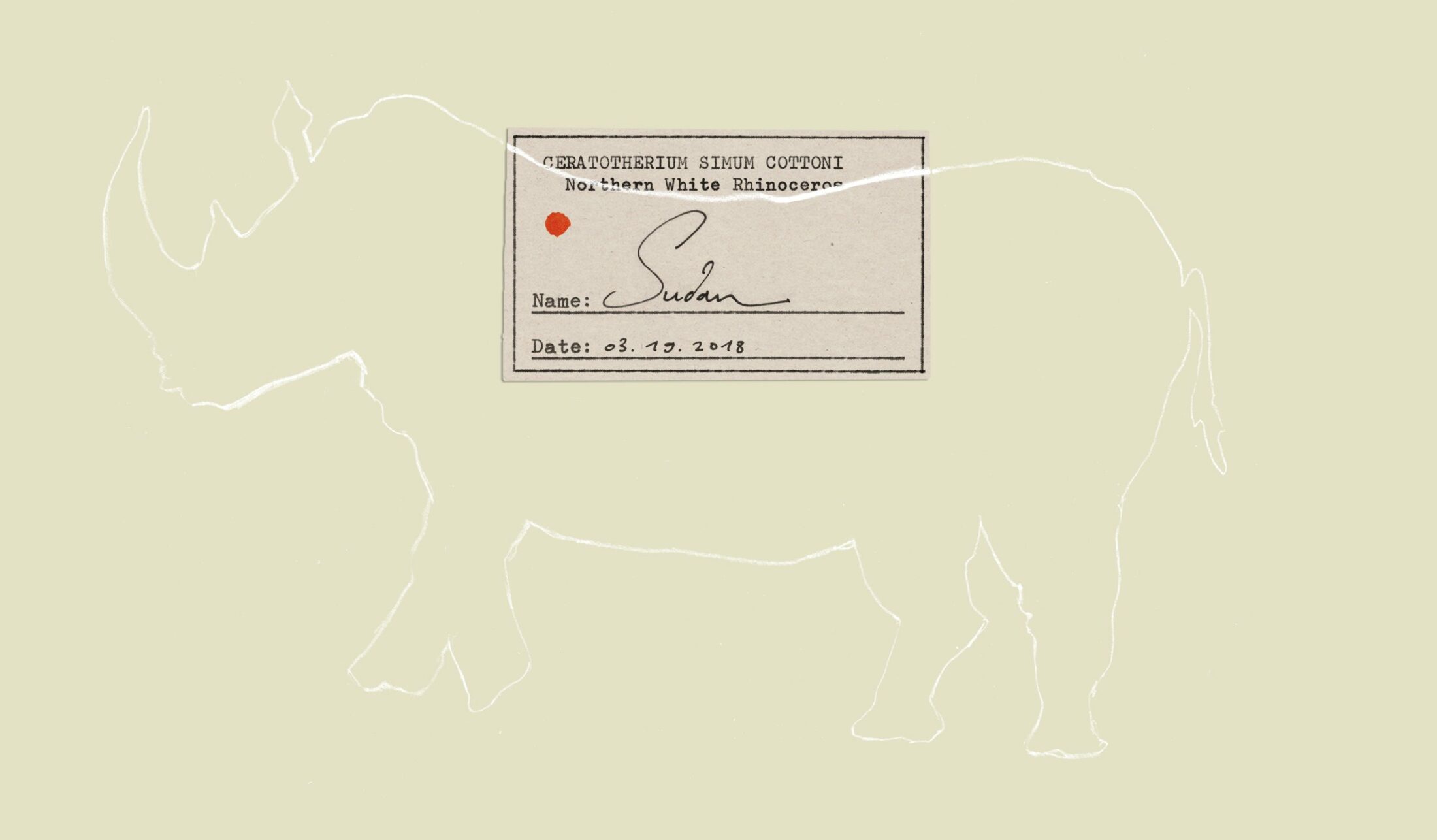

Sudan, the last male northern white rhinoceros on the planet, left the planet in March 2018.

Born wild in the Sudanese savanna some forty-five years earlier, he was captured young and spent most of his life in a Czech zoo. It can be cold in that country. Far colder than more than a million years of evolution prepared pachyderms to bear. Hoping that a more hospitable climate would support the longevity of the critically endangered species—there were only eight left in the world at the time, down from an estimated 1909 count of two to three thousand—in 2009 conservationists transferred Sudan to a Kenyan preserve. There he grazed under twenty-four-hour guard.

Why the guards? Again, the names we’ve chosen to speak of Sudan’s life seem also to name his loss. The ivory that earned him the name “rhinoceros”—meaning “nose horn”—can sell on the black market for as much as $30,000 a pound, though rhino horn is built of the same stuff as human nails. As was true for both the snail and the tortoise Georges, humans (horn poachers, not shell poachers, this time) are largely to blame for the fact that the last male northern white rhino is survived by only two females: Sudan’s daughter and granddaughter—Najin and Fatu, respectively—both beyond breeding age.

Think of this: though Najin and Fatu are surrounded day and night by guards set to prevent their disappearance from the Earth, every other rhinoceros who has ever been related to them has already died. That is a kind of loneliness for which we don’t have adequate language.

In the Oregon house, where Carolyn was dying, the rest of us talked and talked, without really listening to one another. The Occupy movement was in full swing. I’m using that language intentionally. According to Dictionary.com, the phrase “in full swing,” “dating from the mid-1800s, alludes to the vigorous movement of a swinging body.” There seemed to be so many people involved in the Occupy movement at the time. From our vantage points in cities like Oakland, Portland, and New York, where Occupy encampments housed hundreds of activists, it seemed that there was a vigorous movement, a swinging of the body politic in a new direction. None of us who’d gathered to say goodbye to Carolyn were particularly young, but maybe we were dumb. We were full of hope and the language that comes along with hope. We believed that substantial and sustainable global change was on the horizon. So, yeah, we must have been dumb.

Was that silly of us? Maybe it was silly of us. Who of us hasn’t ever been fueled by folly? Though Carolyn’s imminent death brought us together, we didn’t consider the possibility of irrevocable loss on a national, even planetary, scale. We passed pasta around the table and continued to babble—until Carolyn reminded us of the things we could miss in this world.

Rhinos are an umbrella species, by which term conservationists mean that the presence of the animals—and their protection—shelters many lives in a shared habitat. Save the rhinos and you might also save some of the birds and zebras, the invertebrates, the flora, and the fish that share the same ecosystem.

Consider the oxpecker—the tick-eating bird known as the askari wa kifaru, or “rhinoceros guard,” in Swahili—who makes meals of the ticks and other parasites that burrow in rhinos’ thick-skinned hides. Consider the cattle egret, whose taxonomic name is Bubulcus ibis and who is sometimes called the rhinoceros egret because it is known to follow the huge pachyderms in order to eat the bugs and tiny critters disturbed by those enormous feet. See the rhinos go, and with them the status of these lives will be altered as well. See the rhinoceros go, and the sounds, the songs, of the savanna will change.

I appreciate the word “umbrella” because I understand what the umbrella is meant to do: protect us from inhospitable weather. I also understand the umbrella’s limitations—woe betide the ones under an umbrella if a particularly windy storm sets in. Woe betide the ones too tall or too small to benefit from an umbrella claiming one size fits all. The word “umbrella” reminds me that some of us can engineer survival, but the survival of only some.

Studies suggest that there were once more than 750 species of native land snails on the Hawai‘ian Islands. Studies also suggest that the Hawai‘ian Islands once boasted more varieties of snails than almost any other place in the world. Experts now believe that, largely as a result of several human-driven interventions, more than 90 percent of those populations are gone forever.

I have no words. This is what I used to say when someone died and I didn’t want to sound insensitive, or when someone died and I didn’t want to make an insufficient gesture of condolence, or when someone died and I was so broken up by empathic grief, I didn’t know how to put my feelings into words. When I learned more about the rapidity with which human actions have driven these species to extinction, for a long while, I had no words.

We are lonely. It has taken me nearly a month to put words to the feeling, but that is it.

Folklore of the Hawai‘ian Islands says that once, the island forests were filled with the song of snails. We have no words in our contemporary language to explain this.

One researcher claims that when the people of the islands first heard a piano, they said that it sounded like the singing of snails. This tells me something about the timbre of the snail song, but not much more than that. What song did the pianist play? At what tempo and in what key? I’ve read transcriptions of some Hawai‘ian songs that feature kāhuli, the tree snails. The words to these songs are lovely, but I am sad not to know their melody.

Some speculate that the sound people called the song of the snails was the munching of all those snail mouths on the leaf fungus that fed them.

Some speculate that the sound people called the song of the snails was the squeaking of snail mucus on the leaves of so many trees. No one has verified this, and I resist the theory. There is very little magic in the thought of all that mucus.

Some think the Native Hawai‘ians were simply mistaken, that what they actually heard singing in the forests were birds. This assessment is insulting to the intelligence of Native Hawai‘ians. Also, if it really were the case, why don’t we hear the birdsong anymore?

It is true that by 2018 the poʻouli—also called the Melamprosops phaeosoma or the black-capped honeycreeper, who eats the native snails and worms and insects on another Hawai‘ian island, the island of Maui—was thought to have disappeared from the planet. With the loss of the snails, have we also lost the songs of many a bird?

It is likely that Carolyn died because of the nuclear toxicity in the New Mexican desert she loved to call home, though the simple name for what killed her is “cancer.” Carolyn has been haunting this essay because I mourn the loss of her. She died nearly ten years ago. By the measure of her family’s longevity, she should still have been with us at least another thirty years.

I was lucky to have known Carolyn at all. An accident of my life crossing paths with her daughter’s. I could have missed knowing that either of them existed altogether. I had never even heard of the Achatinella apexfulva or the song of the once-abundant, long-lived land snails of the Hawai‘ian forests until all of them and all of their songs were already gone.

Lonely George. Lonesome George. Sudan. The white rhinoceros’s solitary offspring, Najin and Fatu, too. Carolyn. My friend is lonely now, without her mother.

Sometime during my weekend at the big house in Oregon, my friend and I took a long walk. I wore the barefoot shoes that keep my luggage light. In my California home, where the temperature rarely dropped below fifty-five, those shoes worked perfectly well. They gave me traction, flexibility, and protection while allowing me to stay in close touch with the feel of the earth. But the weather in Oregon was colder than I’d anticipated.

As we walked, my feet grew more and more uncomfortable. The blood that should have been warming my fingers also began to rebel. Carolyn was dying inside, though, so it seemed selfish to complain about the weather.

What I’m trying to say is that most of the time, I am overwhelmed by the feebleness of language. Some current experts suggest that we lose a species every five minutes. Earthday.org estimates that, at our present rate of extinction, each year between 10,000 and 50,000 species will disappear from the planet forever. My fancy shoes and the bulldozed path on which I wore them, and the trees cut down for the box that boxed that disappointing pasta, whose calories my walk was meant to counteract—all are partly to blame.

If shame isn’t the reasonable response to all this loss—or even sadness—perhaps I ought to feel something closer to the matter-of-fact assessment Carolyn made. Maybe I need to find language to directly name how many things there are in this world I will never know.

Trying to find a way to speak to all these losses feels like walking around a denuded arboretum disappointed in myself—and a little panicked—for not being able to picture the trees in full leaf.

Two years before Lonely George died, researchers at the University of Hawai‘i sliced two millimeters from the snail’s foot. The sterile specimen is stored in hopes that one day, by mapping Lonely George’s genome, future scientists might clone another Achatinella apexfulva. Similar laboratories protect the genetic codes of Lonesome George, the Pinta Island tortoise, and the northern white rhinoceros, or Ceratotherium simum cottoni, known familiarly as Sudan.

That’s the sort of drive that found me online ordering bagels and cream cheese after returning home from Carolyn’s hospice house. A drive that pushes against the eradication of all the world could offer.