Anna Robinson, who portrayed Aunt Jemima between 1933 and 1951

Bettman via Getty Images

Life Beyond the Bandana

Retiring Aunt Jemima, Uncle Ben, and Rastus—Finally

Michael W. Twitty is an African-American and Jewish writer, culinary historian, and educator. He is the author of The Cooking Gene, which won the 2018 James Beard Foundation Book Award for Book of the Year and was a finalist for The Kirkus Prize in nonfiction, the Art of Eating Prize, and a Barnes and Noble New Discoveries finalist in nonfiction. His blog Afroculinaria explores the culinary traditions of Africa, African America, and the African diaspora.

Chef and food historian Michael W. Twitty responds to the discontinuation of the “Aunt Jemima” brand and reflects on the ways that Black men and women who were forced to work in slaveholders’ kitchens have been represented throughout history.

At the end of the Civil War, there was a collective scream as many white women among the Southern elite lost a guaranteed cook in the big-house kitchen. As a historical interpreter of enslaved cooks from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, I know but a taste of some of the things they endured. Long skirts and aprons meant frequent burns and horrific accidents; cast-iron pots weighed upwards of sixty pounds when they were full of water, and constant exposure to wood smoke meant suffering a lifetime of bronchitis. Mistakes in cooking could mean anything from having to wear an iron mask to losing privileges like seeing one’s family or, worse, being beaten or even killed. For most Black women and some Black men, the separate kitchen out back or elsewhere on the estate was also a place of sexual violation by slaveholders, overseers, and their children. For the privilege of having a meal and a false sense of love and loyalty, a wealthy white person could pay anywhere from $800 to $2,500 for a skilled Black cook; that’s a starting price of around $26,000 in 2020 currency.

If a slaveholder was lucky—which was especially unlikely if they were of the common sort, with ten or fewer enslaved workers—they might inherit a cook. This person trained under another expert cook who could be traced back to the African women who arrived in waves across three or four generations, who were in turn taught by their mothers; and then the cook would be taught by the mistress of the estate, who trusted her to master Western cooking. These women would raise girls and boys who took on the role of the plantation, farm, or urban-estate cook. To survive, cooks would often feign loyalty and commitment to the white family in order to earn mercy and not be sold or separated from their spouses and offspring. White families nicknamed them “Aunt,” “Uncle,” “Mammy,” but as the line goes in Sherley Anne Williams’s novel Dessa Rose, “‘Mammy’ ain’t nobody name.”

Slaveholders appealed to the freedmen to remain and “help out” after slavery. Those who did were mainly destitute and older, with few prospects for employment or survival on their own. Some formerly enslaved cooks were made orphans and widows by slavery and the war. Others got the hell out and found themselves fiercely chided for their ungratefulness and disloyalty to the slaveholding elite. Out of this chaos, the “slave in a box,” to use the term by scholar Maurice M. Manring, was born into American capitalism to assuage the yearning for the coerced Black helpmate so many had grown up around and depended on for sustenance and emotional support—a person they could psychologically, emotionally, verbally, or sexually abuse and still call “a dear member of our family.”

She was never her own woman. She was a gal, then a wench; then, when she was old enough, “Aunt.” He was never a man; he was a boy, then a buck, and then an “Uncle.” Aunt and Uncle were reserved for those deemed too decrepit and harmless to be a threat to white supremacy; only then did they receive one of these “kinship” names. She was never Miss or Mrs., and he was never Sir or Mr. There was never any expectation that they would walk through a front door or eat at the same table with those they served. They were to settle for a gift of a calico cloth or a shine for their worn and tattered shoes at Christmas, and accept it with grace and feigned enthusiasm.

He wore the clothes of a finely dressed domestic servant, from ruffles to kerchiefs to a bow tie to a pearly white servant’s coat that he was never to stain. Never should the appearance of this man betray the myth that he was treated decently, like a favored pet. Her head wrap was nothing compared with the headgear of her African foremothers, but it kept her hair out of the food and the sweat out of her eyes while she worked in kitchens that reached temperatures of over one hundred degrees. In Louisiana and other localities, it also kept with a custom that discouraged Black women from showing their natural hair.

Enter into this setting the mocking of Black men and women through the minstrel show. Black mannerisms, speech, attire, music, and foodways were mocked as “old,” and native European immigrants became white together by gazing and cackling at the Black other. Aunt Jemima pranced across the stage as early as the late 1800s, but by the time Chris L. Rutt, founder of the Aunt Jemima pancake recipe, saw her, she was a third-rate copy. According to the author of Black Hunger, Doris Witt, “she” was a white man named Pete Baker, portraying a German in blackface portraying a minstrel portraying an enslaved woman cook.

Into this world stepped Nancy Green, born into enslavement (please don’t ever again say “born a slave”) on a Kentucky plantation in 1834. After she became a cook for a judge in Chicago, he recommended that she model for a company that was coming up with a ready-to-cook pancake mix and needed an authentic Black southern cook to dynamically demonstrate her kitchen magic at its space at the infamous Chicago World’s Fair in 1893. She charmed them, an artist rendered her, and without her approval, a part of the Black culinary legacy bearing her corrupted likeness was imprisoned on a box for nearly a century.

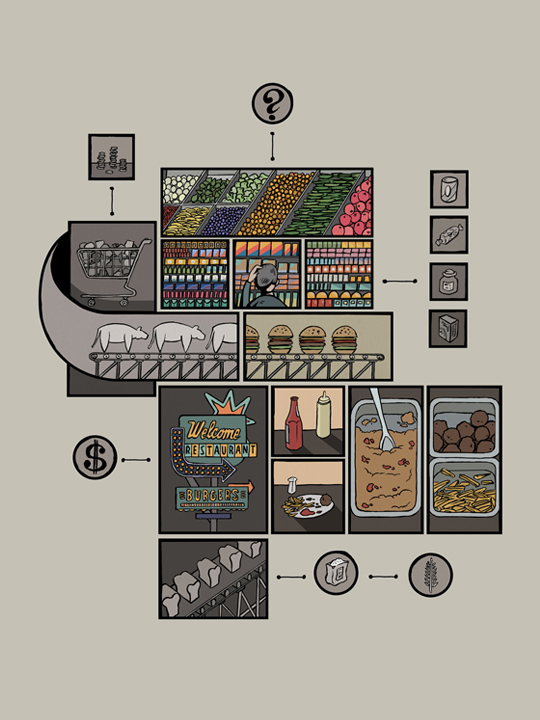

On those boxes, she and “Rastus”—and later, “Uncle Ben”—became symbols of what the product was to the consumer. Quaker Oats, the owner of the Aunt Jemima brand since 1926, was likewise a metaphoric representation. Just as Quakers were considered sound and wholesome, plain and authentic, these “slaves” on boxes represented loyalty, submission, a readiness to serve, and selfless dedication. On another box: somewhere, in a place of land and lakes inspired by the legend of Hiawatha, an Indigenous woman emerges in all of her native garb with her butter, just as simple, organic, and natural as she was, gently and blamelessly placed on a lower rung of the hierarchy of man, a noble savage.

In 1989, in my lifetime, Aunt Jemima emerged anew just in time for her one hundredth birthday: The pearly teeth were decidedly paired with pearl earrings. The red of her calico shifted to a neat collar, and her hair was uncovered, just in time for it to be a polite, steely gray. And yet, by that time, the damage had been done. Aunt Jemima had been background inspiration for an attempted “Mammy memorial” on the National Mall, proposed, perhaps not coincidentally, in 1923, the year Nancy Green died. Then came Gone with the Wind and Imitation of Life and Beulah and radio ads in stylized “Negro dialect.” Aunt Jemima made the lives of pleasant white people more pleasant; she was ready to satisfy their suburban hunger in the 1950s commercials and even had a “kitchen”-type concession at Disneyland, with her grin frozen in time.

Now, in the midst of national turmoil, a reassessment of race in America, after years of side-eyes and grumbles, tired, beleaguered Aunt Jemima and Uncle Ben are on their way out. But not before scholars like Psyche Williams-Forson, Toni Tipton-Martin, Doris Witt, Rebecca Sharpless, M. M. Manring, and others had to deal with her legacy to make room for the real culinary history of African Americans. For Tipton-Martin—a two-time James Beard Award winner, most recently for Jubilee—“the Jemima Code,” also the title of her first signature book, refers to the way that over the generations, the contributions of African American cooks, mainly women, were couched in harmless, subservient, and floral myths of mystical talent that obfuscated their intellect, power, and importance.

As some mock this loss as political correctness gone overboard, an offense to the compassion they extended to their personal enslaved person on a box—a harmless image they suggest is a form of valid Black representation—we don’t share many tears. When I was a small boy, my first “n-word moment” was when two older white kids ran past our porch screaming, “Hey, Aunt Jemima! Hey, Uncle Ben!” at my grandmother and me. She became irate and I became teary. I didn’t understand what I had to do with those people on boxes who did not look like me and reflected back at me a past that I hadn’t even learned about—a baggage, a load, that I was utterly unprepared for; a nasty and singular legacy that, whether I liked it or not, was mine to bear from the cradle to my grave.

Now, as a historian of food, one who dresses in the civilian clothes of early America at a plantation museum, I often have to fight off these demons in front of audiences Black and white. For many Black people, it is hard to detach these traumas of marketing from the idea of a Black person interpreting the foodways or other arts of enslaved Africans. I have been called “Mammy” and “Uncle Tom,” just for being in a field where there is little Black representation. For some white people, it is a welcome symbol that somehow I have accepted without self-critique a caste status that was just a sign of the times. Or, worse, that I sympathize with them because I am willing to plumb the depths of food, interpreting history, via America’s other original sin. When I open my mouth and remove all expectation that I am there to comfort them, I get called a “race-baiter.”

In the face of all this Sturm und Drang, I am not retiring Aunt Jemima, Uncle Ben, or Rastus. I am putting a spell on them, banishing unhelpful myths into the ether. There is no tomorrow for them. I will continue to teach about the roads to freedom, entrepreneurship, revolts, and resistance against enslavement that began in those old kitchens by the hands of Black cooks. I am killing them so the real stories can live, unchained to stereotypes and lies. I will continue to name the actual names of the men and women and children who set the American table in the Eastern Seaboard and Deep South and forged a new way of eating. I will do this because Mammy “ain’t nobody” name; nor was Uncle Ben or Rastus; and sure as biscuits need syrup, Aunt Jemima wasn’t anybody’s name, either.