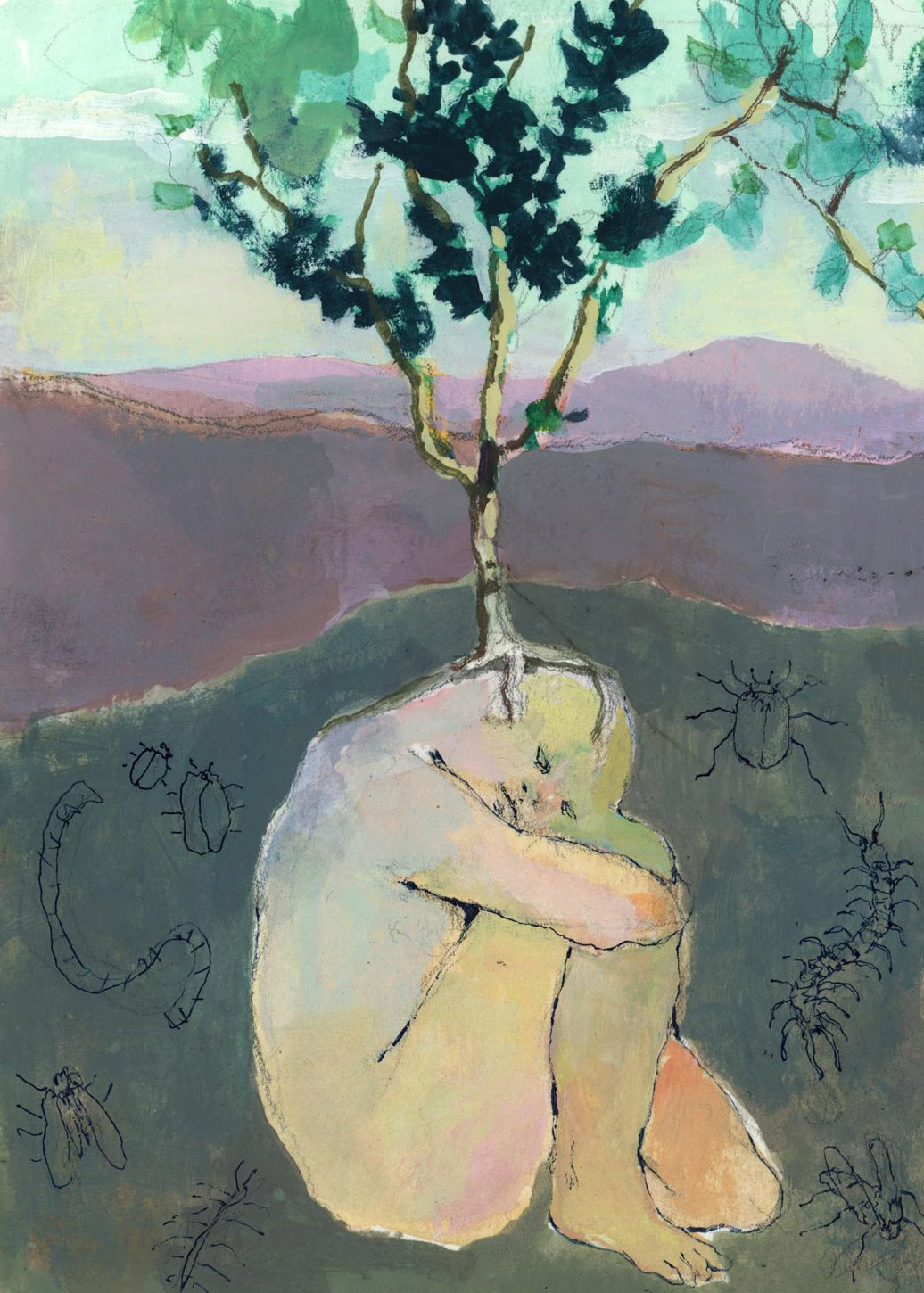

Buddhist monks ordain trees to protect them from logging in one of Cambodia’s “monks’ community forests.”

Photo by Chantal Elkin, courtesy of ARC

Hallowed Ground

by Chelsea Steinauer-Scudder

Chelsea Steinauer-Scudder is a writer based in northern New England whose work explores the human relationship to place. Her essays have been featured in Crannóg Magazine, Inhabiting the Anthropocene, and EcoTheo Review. Her forthcoming book is Rebirth: Mothering Through Ecological Collapse.

The roots of religious belief and the sacredness of nature were once closely entwined: the ancient yew grows in the churchyard; the forest monks of Thailand follow the Buddha’s example of meditating beneath trees. Chelsea Steinauer-Scudder profiles theologian Martin Palmer and his work to engage faith-based communities in recovering narratives of love and care for local ecologies.

The yew, Taxus baccata of the family Taxaceae, is a conifer native to the United Kingdom. Growing up to twenty meters (sixty-six feet) tall, and sometimes taller, with peeling auburn bark and small, straight needles that grow in two dark-green rows, yews provide habitat for the goldcrest and other small birds. Every part of the yew is poisonous, with the exception of the bright-red, fleshy arils that encase the seeds, food for the blackbird and the mistle thrush. Yews are the oldest living things in Britain, considered ancient only when they reach the age of nine hundred. Some are believed to be at least five thousand years old. Yews carry an air of the secretive, and their age is notoriously difficult to determine because of their ability to withstand extraordinarily long periods of dormancy and then mysteriously decide that the time is right for new growth. Some of Britain’s oldest yews have witnessed Roman expeditions led by Julius Caesar, ancient Celtic ceremonies, Anglo-Saxon conquest, and the Black Death.

The Fallen Giant is one of the ancient yews of Druids Grove in Norbury Park, south of London. It was partially uprooted in 1720, and for the next three hundred years it lay still: “coiled up as in mortal agony,” according to an 1842 edition of the Athenaeum journal. Fresh green needles did not emerge from its twisted branches. Around it, histories unfolded. Religions waxed and waned. A modern world sprang from the ground in every direction. All the while, the Giant’s kin stood nearby—the Horse and his Rider, the King of the Park. Trees old enough to be recognized, given names.

In 2018, after three centuries of silence, the Fallen Giant put out a new branch.

Ancient yews, ghastly looking beings, were respected and feared by the Druids, the Celts, then the Christians, for this tree can at once be dead and reborn: new shoots can grow round a hollow, decaying trunk. The yew’s deadly toxicity, its ability to return to life from apparent decay, and its longevity have granted the tree a complex symbolism. In ancient Greece, yews were associated with Hecate, the goddess of witchcraft and necromancy. The Druids used the yew in death rituals. In Celtic traditions, yews symbolized both death and resurrection. Christians buried yew shoots with the deceased and used boughs of the tree as “palms” at Easter. One will almost always see yews growing on the southern or western sides of a church—where the dead are buried.

A number of these long-lived beings still stand today. Many of the oldest yews in Britain survive because churches were planted alongside them. The presence of the churchyard protects the yew, or the presence of the yew drew the church to hallowed ground. It is not often known which was there first; sacred roots intertwine. The ancient relationship between the churchyard and the yew is often forgotten in a modern world. Not dead, perhaps, but, for now, dormant.

Two yew trees grow on either side of a door at St. Edward’s Church in Stow-on-the-Wold in Gloucestershire, England.

Photo by Steve Taylor ARPS / Alamy

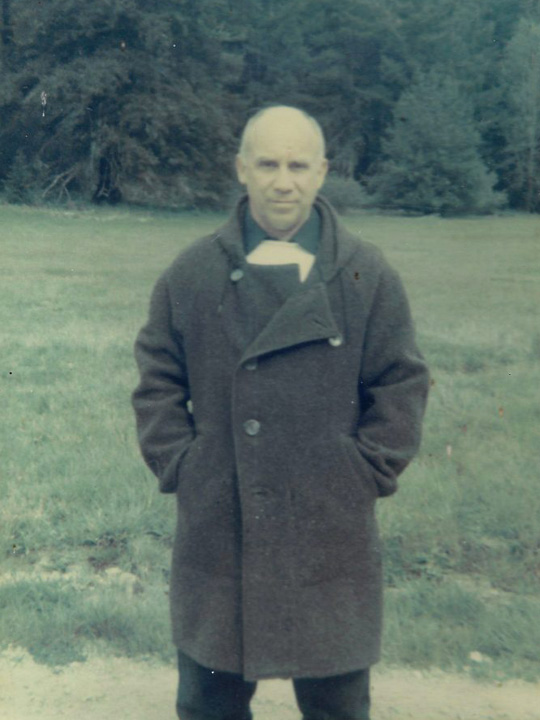

I am waiting to meet Martin Giles Palmer—theologian, Taoist scholar, radio personality, and secretary general of the Alliance of Religions and Conservation (ARC)—at the porch of the Bristol Cathedral, England’s most acclaimed medieval hall church, on the College Green. The church is beautiful, imposing—embellished with such elaborate detail that it is impossible to take in with a casual glance. One could spend an entire day simply gazing at the exterior: four somber, laconic men carved in weathered stone, a panel of the Virgin Mary and child resting above the entrance. Thousands of intricate details represent decades dedicated to carving and assembling stone. But few passersby on this muggy and overcast day in June pay the twelfth-century building any attention; far fewer enter. I loiter outside long enough that a hopeful woman pokes her head through the door, assuring me that it’s okay to come in. On another day, I would have welcomed an afternoon of being overtaken by the soaring aisles with ceilings that rise to the same height as the vaulted nave, the starburst recesses, the uncanny, delicate light of stained glass. But just then, Martin appears, a sprightly man in his midsixties. An intellectual in a pink shirt and trim beard. The sort who, even when holding still, manages to appear busy, as if he’s five steps ahead of himself.

I’m to accompany him for two “readings” of the sacred layout of Bristol’s Old City: one based on medieval Christian theology and one on the ancient Chinese tradition of fêng shui. Martin—whose work with ARC focuses on connecting faith communities and their teachings to their landscapes, environment, and sacred histories—can trace his own family’s religious history back five hundred years to Bristol’s time as a lively pilgrimage port. “I’ve always been fascinated in the history of my land—the burial mounds, the stone circles—as much as in the churches and the cathedrals,” says Martin, “because for me they were all about the fact that the questions ‘Why are we here?’ and ‘What happens after death?’ have been asked in this land, as they’ve been asked everywhere, for thousands of years. And these places were where people found some way of articulating their answer, or at the very least their questions.”

Cities like Bristol were originally laid out as physical models of humanity’s place in the cosmos. The Christian theology of the medieval Normans can still be seen here, nestled into walls and hidden in corners of this modern city, buried beneath cafés and restaurants and pavement. As we set off across the College Green, Martin begins turning over the stones of history, dusting off sacred stories like an archaeologist with familiar relics. The central crossroads of the Old City, today the intersection of Corn and High Streets, is laid in the shape of the Celtic cross, with the circle formed by the old wall and the Rivers Frome and Avon, symbolizing the love and unity of God. The particular curve of a small road near the top of the cross depicts the head of Christ at the moment of his death. North is the direction of danger, from which Saint Michael threw Satan from heaven. East, toward the rising sun, is the direction of paradise.

Different churches, built for various saints, are set into the symbolic landscape. St. Nicholas Church, named for the guardian of sailors, overlooks the river and Bristol’s original bridge. Saint Stephen—the first Christian martyr, stoned to death outside the city walls of Jerusalem—accordingly has his church located just outside the walls of the Old City. St. Peter’s, Holy Trinity, the list goes on. Every cornerstone was once an intention; each holds meaning in the layout of the city. Whether or not residents and tourists know it, we are all walking through the stories of a sacred map—stories that we in the West have largely forgotten, that speak to our connection to what we once understood as the foundation of a sacred reality: the world around us. Far beyond the walls and central cross of Bristol are rivers, hills, stones, and wells that were once alive in our understanding.

“You take out sacred things at your peril,” Martin says. “You’re changing the map of where you live.”

Far beyond the walls and central cross of Bristol are rivers, hills, stones, and wells that were once alive in our understanding.

There are Theravada Buddhist monks in Thailand who follow the Buddha’s example of meditating in natural settings, particularly beneath trees; they have a practice of going into the forest during the rainy season of Phansa and building small huts, where they remain for several months to meditate. Traditionally, when the huts appeared, it was understood that human beings were not to disturb or damage the surrounding forest; it became an extension of the monks’ prayers and practice: sacred land.

Thailand and Cambodia have seen some of the most devastating logging and clear-cutting in a world where 18.7 million acres of forest across the globe are lost to deforestation annually. Between 1961 and 1998, an estimated two-thirds of Thailand’s remaining forest was destroyed.

In the 1980s, the logging effort increased and entire forests began to disappear, sometimes in the course of a single day. In 1988 the excessive deforestation of a mountainside led to a landslide, exacerbating floods and killing over three hundred people. The monks saw the land suffering and the people suffering as a result. A small number of monks began to reexamine Buddhist scriptures, seeking ways to protect the forests through traditional rituals and teachings. The Buddha taught that all things are interconnected, that the health of the whole is bound to the health of every sentient being. If you harm rivers, trees, animals, soil, you harm yourself. Some of the monks began to intentionally seek out threatened and illegally logged forests for their Phansa meditation, but it became increasingly dangerous for them. Some were assassinated.

And then one monk began a practice of ordaining trees. After locating the oldest and largest trees in a forest, he—in the presence of members of his surrounding lay community—recited the appropriate scripture and then wrapped the trees in traditional orange robes, just as is done for a novice monk. The practice has spread across Thailand and into Cambodia.

Most loggers will not commit the taboo of harming a monk, even if that monk is a tree.

A Buddhist monk patrols one of Cambodia’s “monks’ community forests,” protecting it from poachers and developers.

Photo by Chantal Elkin, courtesy of ARC

“We are a narrative species. The faiths are successful because they tell bloody good stories and they adapt them as they go along,” Martin is telling me over a coffee break in Bristol. “So all across Southeast Asia, there are these trees that have been ordained as monks, and that means that within a sort of half-mile penumbra of that, it’s sacred. There’s no way a Cambodian or a Thai is going to cut down a monk tree.” ARC has worked with monks in Thailand and Cambodia to set up environmental-education centers, trainings, and awareness campaigns. It helped to found ABE, the Association of Buddhists for the Environment, a network of Cambodian monks and nuns grounded in Buddhist teachings and traditions. “It’s been very local, very specific [work]. And most of it is built on the fact that, whatever else is gone, a sense that a sacred place is something other still remains.”

It’s this sense of sacred place and the stories that go along with it, Martin says, that can become catalysts for change. When it comes to addressing ecological degradation and potential collapse, most of us have not been telling the right ones. A transformative story, when told at the right time in the right place, has the ability to alter the course of things. “There’s only two things that have ever done that successfully in history: art and religion. And for most of history, they’ve been synonymous,” Martin says. ARC works with Jains in India, Shintōists in Japan, Taoists in China, Jews, Muslims, Zoroastrians—operating on the belief that religion has consistently told humanity’s most enduring stories, that parable can be more effective than science, that myths are more powerful than data.

As we wend our way through the city, I’m beginning to picture Martin as a real-life, intellectual version of Roald Dahl’s BFG: a lanky, well-intentioned giant who roams the globe, but instead of collecting dreams and delivering them to sleeping children, he is collecting stories. Fables and myths, parables and songs. His life’s work has been to pull forward or uncover narratives from traditions and texts, and support local faith communities in doing the same.

“You take out sacred things at your peril.”

Martin grew up in a middle-class family in a housing project on the outskirts of Bristol, far outside the now hidden walls of the Old City. His godmother would take him on walks across the Quantock Hills, pointing out fairy circles, reading old churches, narrating battles between giants and serpents. His father was an Anglican priest. His mother was a psychotherapist and conservationist who planted trees and was the sort to stand between teenagers and the pigeons they were throwing stones at. She was an atheist until she met Martin’s father and then became a “sort of” Christian.

When he was fifteen, Martin himself became an atheist—“You have to if you grow up in a vicarage; otherwise you’ve got no self-respect”—but returned to his faith while studying theology, when assigned to do a literary and historical criticism of the synoptic Gospels. “I went into it as an atheist thinking, right, I’m going to demolish this, going to show there’s nothing here, you know, rip it apart. And I ripped it apart, and there was still something there I couldn’t dodge. I’m still trying to dodge it.” Today Martin, though not a priest, leads services at his local Anglican church. “Ever since I became a Christian with this deep history of ancient Britain behind me and walking the landscape … I’ve known that there are many different stories. And for me, the Christ story makes more sense of the good, the bad, and the ugly of human life than any other story I know. But it’s not the only story.”

When he was eighteen, Martin went to work at a children’s home in Hong Kong. He lived with an Anglican family; every night at chapel, they would sing from a thick hymnal, published in Chinese. Slowly, Martin began to decipher individual words, and then entire songs. “I learned to read classical Chinese from a hymn book.” It was the beginning of a lifelong fascination with Chinese culture, religion, and thought. “My Christianity is deeply shaped by my Taoism.”

The sacred layout of Bristol, he tells me as we continue our tour, can be just as easily read in Chinese terms. The Frome and the Avon, a fast and a slow river, are yin and yang. North is the direction of danger in this cosmology as well. That the city makes sense both through Chinese fêng shui and Christian theology is not a coincidence, says Martin. Religious stories are often different articulations of the same questions. Faith, more than anything else, has determined the human understanding of place throughout history. If one knows the teachings and narratives of a local religious tradition, one can almost always find traces of them in the landscape.

But such traces are increasingly just that: echoes of sacred sites obscured by a secular world. Indeed, to the present-day observer, modern Bristol does not feel like a flourishing center of spirituality. “Northwest European exceptionalism [means] that secularism is rampant, that religion is considered a private matter of very little significance,” says Martin. “Whereas in the rest of the world, religion is just how you live, it’s who you are. It’s not something to be … stuffed away and brought out on a Sunday. It shapes everything. And so our problem is that in Europe—especially northwest Europe, which is Protestant, of course—we stripped out our holy wells, our sacred rivers, our sacred mountains.”

“The municipal sacred,” Martin remarks, glancing around at the structures and facades that take precedence in the layout of modern cities: shops, banks, advertisements, pubs. Around us, these are the entities that seem to guide the movement and direction of Bristol’s crowds. “Does it transcend or does it just replace? … This doesn’t take you anywhere.”

A map of Bristol’s medieval Old City.1

Intensive agriculture, development, and the ongoing impacts of climate change have depleted ecosystems across Britain, where the majority of native species are in decline and one in ten is faced with extinction. Hedgehogs, bees, hoverflies, and birds are losing habitat. Biodiversity is on the decline, though this is not at all unique to Britain. The loss of pollinators in particular could cause humans to lose the habitats and ecosystems that we, too, depend upon.

But there are plots of land all over Britain, in nearly every city, town, and village, where one is almost always able to find a small patch of green space, often with native flora and fauna: churchyards and cemeteries. The presence of churches, often simply by default, protects attached grasslands and meadows, woodlands and shrubs, even rare lichen species on gravestones. The Living Churchyards project, launched with the assistance of ARC in the nineties, encourages parishes to protect these spaces intentionally: God created the world, and we must honor that creation. The project has taken on a momentum and life of its own. Local environmental organizations like the Dorset Wildlife Trust have partnered with parishes to manage churchyards as havens for wild plants and animals. Across Britain, more than six thousand churches now manage their connected lands and lawns as living churchyards, with no pesticide use, limited mowing, and education of their parish and congregation.

“Part of our work has been to find the people who have the authority, the power, the budget, and the structures to deliver. So it isn’t just lovely words that we can all sit and meditate on—that’s part of it, but it’s not going to change the world. It’s actually showing that you can do something locally, like the living churchyards,” says Martin.

ARC was in its infancy at the time of the Living Churchyards project. Previously, Martin and Prince Philip had been working with the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) on proto-ARC projects, getting WWF involved with faith communities on environmental issues. When the two decided to break away and launch ARC, Prince Philip’s involvement gave the organization legitimacy and a greatly extended reach. Martin by then was well connected in China, appearing on Chinese TV and radio programs and locally on the BBC as a scholar and theologian. ARC was primed for success, but in an increasingly secular world that had little interest in what religion had to say.

But Martin has witnessed a shift. “Up until maybe as little as four or five years ago, possibly even slightly less, if you talked to people about a relationship between religion or spirituality or faith and environment or development or sustainability, people looked at you as though you’d escaped from some lunatic asylum,” he says. The great disappointment that was the climate agreement at Copenhagen in 2009—after which the Guardian published an article with the headline “Low Targets, Goals Dropped: Copenhagen Ends in Failure”—was the beginning of a changing attitude toward faith communities on a global scale. World political leaders—after years of buildup, international pressure, and mobilization—had failed to take any meaningful action or make lasting commitments to address climate change. The nongovernmental organizations and environmental groups that had long lobbied them began to lose confidence in governments as catalysts for change. (“Governments, you know—” says Martin; “it’s rather like cream: the thickest rise to the top.”) Organizations began instead to turn their attention to civil society, and once they did, it became much harder to avoid religion, says Martin. And so, when the United Nations and other secular international organizations started to wonder aloud whether and how to engage the faiths in climate initiatives, ARC was an obvious place to turn.

By then, religious communities around the world were taking serious steps to address the environmental crisis. Pope Francis came out with his environmental encyclical, Laudato si’, in 2015. Later that year, ARC partnered with the United Nations Development Program to launch the Bristol Commitments, faith-based responses to the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals. Representatives of twenty-four religious traditions and denominations gathered for a multifaith celebration in Bristol, and each faith group presented its own list of goals: The Bunyoro Kitara Diocese of the Church of Uganda laid out its “Mitigation of Climate Change Project,” a ten-year plan to reforest the surrounding lands, improve farming methods, and create eco-schools. The Chinese Taoist Association pledged to expand its fasting calendar to reduce the consumption of meat, dig wells for clean water, and continue its summer camps to bring urban youth into the forest. The Hindu Bhumi Project committed to training young people in environmental leadership and publishing a “Hindu declaration on climate change.”

The world’s religions own around 8 percent of habitable land on earth and 5 percent of commercial forests. Around half of the world’s schools were founded by, and continue to be run or managed by, the world’s religions, who also own approximately 10 percent of total financial investment across the globe. Religions continue to wield power. Martin believes that this power is rooted in and serves to benefit the collective. But in the United States and Britain—and many other industrialized countries—people are less and less likely to identify with any particular faith tradition. Only 8 percent of adults between the ages of eighteen and twenty-four in Britain identify as Anglicans or Catholics, and the number is trending down. Community and a shared sense of identity and responsibility, even in a secular sense, are on the decline. At the same time, people are increasingly likely to view themselves as autonomous individuals. It is difficult to imagine how these collective, rooted stories of connection and care will resonate with people and, indeed, entire societies that have less and less context or language for hearing them. Can an ancient story, meant for a local community, be successfully planted in a modern, atomized, globalized world?

We can find new ways to tell ancient stories. New language to bring people back to an ancient understanding.

Martin is, for the most part, optimistic and, in moments, uncertain. In his view, it’s not only landscapes that have been largely stripped of the sacred; the church, too, has in many ways lost sight of the narrative. Much of today’s religion is caught up in the same dangerous stories as everyone else: capitalism and consumerism “gone berserk,” he says, not to mention individualism and narcissism. “I’m not sure that the institutional religions that we have at the moment are capable of making those changes,” says Martin. “They now exist for themselves, not for something bigger … Many of them have reacted to this withdrawing, this retreat of people from formal religion, by either despair or by aggression. And neither of those is very healthy. What they haven’t recognized is that for some reason, this language, the conventional language, doesn’t work any longer. It just doesn’t work.”

But Martin has confidence in the church’s ability to evolve and change, to appear in new forms. The human-made institution of religion as it exists today may be too rigid to adapt and may ultimately break, but the central stories and beliefs that underlie it are stronger, more expansive, than any time-bound human form they may take. “This is not the first time that there have been these great, huge changes. This has happened many times in human history.” Our ecological crisis might well foretell the dissolution of old structures, religious or not, but Martin also sees opportunity now, today, to give shape and direction to new forms of faith that could emerge. “What we need are … much more local stories.… We need to give people confidence to rename things and to recover names of things and, in a sense, to become much more local in order that we each have something to contribute to the more global.”

To seek and reveal stories on behalf of others is, in many ways, a fraught strategy; it can carry the odor of imposition when it comes from outside a local culture. But in a time when perhaps the most imposing and pervasive story of all—consumerism—is driving species to extinction, deforesting lands, fueling wildfires in the American West, and depleting topsoil and the oceans, one wonders how we can help one another to turn our attention and efforts to different ends. How can we remember that stories, too, have agency? ARC, as an organization, is international, but its lifeblood is comprised of communities around the world, each facing their own version of environmental crisis, each working within the narratives and traditions that have shaped its landscapes and identities. Such stories cannot be arbitrarily deposited. In order to thrive, they need fertile soil, a caring hand, relationship, understanding, shared history. When the conditions are right, they can root themselves or unfurl a new leaf.

“[Religion is] not the silver bullet,” Martin says. It certainly should not be left to faith communities alone to cultivate the stories that might begin to heal a world in crisis, environmentally and spiritually. But he does believe that religion holds our most enduring stories, told again and again throughout the ages, even when humanity sometimes uses them to destructive ends. Secular communities can look to the faiths as examples of what it means to embody powerful narratives. Religious or no, we can find new ways to tell ancient stories. New language to bring people back to an ancient understanding. “Human beings are capable of extraordinary change if given the space to do it,” says Martin. “Not by fear, and not by data. But by story.”

Martin Palmer at the Ise Grand Shrine in Japan.

Photo by Alexander Mercer, courtesy of ARC

In 1999 the world was preparing for the turn into the new millennium. London was in the process of building its infamous Dome. Many were predicting widespread collapse of computers and erasure of data.

In the midst of this, church leaders lined up in cathedrals across Britain to collect yew saplings, taken from trees that were alive at the time of Christ.

Two-thousand-year-old trees. Timekeepers. Witnesses.

Eight thousand yew saplings were subsequently planted in churchyards. It is believed that a small handful of them will still be alive in another thousand years.

The yew has a much longer view of time than we do. Kingdoms will rise and fall. Governments and corporations will come and go. Stories as they are told now will fall away; they may appear again in new forms, or unexpected ones might take their place. Some of these yews, perhaps, will encounter conditions that cause them to go dormant, fall silent, enter a state of decay and seeming death. They may only be waiting patiently for the right conditions to put out a branch, lined with green needles; waiting until they are ready to flourish again in a world and environment that we cannot currently imagine. For now they are small and tender, both new to this world and very old, taking root on sacred ground.

- William Smith, cartographer, Brightstowe, 1568, 33 x 49 cm, in Civitates Orbis Terrarum, vol. 3 (Cologne: Gottfries von Kempen, 1581).