Fermenting Culture

David Zilber is a chef and photographer from Toronto, Canada. He has cooked from coast to coast across North America, most notably as a sous-chef at Hawksworth Restaurant in Vancouver. He has worked at Noma in Copenhagen, Denmark, since 2014 and has served as director of its fermentation lab since 2016. He is co-author of The Noma Guide to Fermentation.

Emmanuel Vaughan-Lee is an author, Emmy- and Peabody Award–nominated filmmaker, and a Sufi teacher. He has directed more than twenty documentary films, including Taste of the Land, The Last Ice Age, Aloha Āina, The Nightingale’s Song, Earthrise, Sanctuaries of Silence, and Elemental, among others. His films have been screened at New York Film Festival, Tribeca Film Festival, SXSW, and Hot Docs, exhibited at the Smithsonian Museum and London’s Barbican, and featured on PBS POV, National Geographic, The New Yorker, and The New York Times Op-Docs. His first book, Remembering Earth: A Spiritual Ecology, is forthcoming from Shambhala in summer 2026. He is the founder, podcast host, and executive editor of Emergence Magazine.

In this in-depth interview, David Zilber, director of the fermentation lab at Noma—named the best restaurant in the world—discusses how food is culture, but fermentation is culture on a deeper level.

Transcript

Emergence MagazineYou direct the fermentation lab at Noma, the acclaimed Copenhagen-based restaurant run by René Redzepi. Perhaps you could start us off and explain both what the fermentation lab is and what role it plays for the restaurant.

David ZilberSo, it’s not normal for a restaurant to have a fermentation lab. It’s normal for a restaurant to have a dish pit; it’s normal for a restaurant to have a service kitchen; it’s normal for a restaurant to have a bar—but it’s not normal for a restaurant to have a fermentation lab. But Noma is not a normal restaurant in any sense of the word.

Noma started over fifteen years ago, and now we’re going into our sixteenth year, as a very simple restaurant with big ambitions. At the start, in November of 2003—many years before I ever walked through their doors, and about the same time I actually started cooking—René had a team of eight people in a sleepy corner of Copenhagen in Christianshavn, and he was mandated to build a Nordic restaurant. And for him that meant exploring the region, taking a research trip to the Faroe Islands, and Iceland, and Sweden, and Norway to understand what was growing out there and to try and invent a cuisine that fit into the manifesto of new Nordic cuisine. And that was a manifesto created by a group of chefs in the region to cook with things from the region, to identify what the soul of Nordic cuisine was, what the soul of the history was that had led up to this point in terms of gastronomy.

Before Noma opened, Nordic gastronomy, Danish gastronomy, was nothing but meatballs and potatoes, and anything considered fine dining had its roots in French cooking. But René wanted to do things a little bit differently, and he wanted to focus on the things that were growing in the place that they were from—time and place—which was the title of the first proper Noma cookbook.

Soon into those explorations—into the explorations of the wilderness and foraging—they realized that they had to do this a little bit more academically, with a little bit more structure, than just going out, picking wild horseradish, and then asking a random forager or a guy with a van to bring back enough for a week’s worth of services. That would happen, and the horseradish wouldn’t taste as it did when René went out and picked it himself. And then he’d ask, “Why isn’t this spicy? This just tastes like any other herb.” [And the forager would say], “Well, this is horseradish, but you asked me to get wild horseradish, and you know there’s one hundred and fifty different varieties of wild horseradish that grow in the Nordic region.” And René was like, “Jesus. Well, okay, we have to figure this out then, because there is no catalog.” And that birthed the Nordic Food Lab.

That was a cooperative project between Copenhagen University and the restaurant, Noma, to catalog the edibility of the Nordic region and to figure out what was growing where, and when. What did people eat? What did they do with it? And how did it make sense in the context of what Noma was trying to do? And to the world at large, how would all of this creation of knowledge feed back into the world? It was meant to be a project that had a purpose, to fill in a gap of knowledge in the world in general.

It also conveniently served as Noma’s first test kitchen, because the researchers in there could mess around with plants and figure out: If you can’t eat this, can you manipulate it? Can you turn it into something else? Can you make a stock from it? All of these little, tiny experiments and concoctions would end up being novel new ingredients in Noma’s kitchen and pushed it into the direction that it was already going, but at an even more accelerated pace.

And through their research, eventually they figured out that a big part of Nordic tradition is preservation. There’s lots of salted fish, like saltfisk, lutefisk, fish conserved in salt, fish conserved in lye: all sorts of different ways of preserving foods. And one they happened upon was salted capers. Now we all understand capers—the berry of the caper bush that you would have in a pasta puttanesca or something like that—but people made capers from other things in the Nordics as well, one of them being the buds of wild garlic, or ramsons, that blossomed in late spring and were packed in salt. So, they started experimenting, trying to make capers. They didn’t really think anything of it. The were like, “Yes, salty things can be chopped up, they can be strewn through marinades, whatever. That seems like a good path to explore.” And some of these salted experiments got messed up. Some of them became accidents. Some of them went in with the wrong proportions of salt to vegetable matter and were tucked away and left to sit for months. Until one fateful day when an old chef who worked in the Nordic Food Lab, Torsten Vildgaard, pulled out a bag that looked a little different from the rest.And he’s like, Oh, I think someone didn’t add the right amount of salt to this. He put a spoon in, took out a very murky kind of cloudy looking liquid, and it wasn’t just salty gooseberry juice: it was completely transformed. It was lacto-fermented gooseberry juice. René tasted it and his world completely changed. It was full of umami, it was full of depth, it was full of lactic acid playing alongside the phenolic acids that came from the berries as well. And it was an “aha” moment, to say the least.

That was the opening of a Pandora’s box, because once they figured out what happened there, they were like, “Wait a second—okay.” Some of the researchers were like, “Oh, well, this is lactic acid.That happened because lactic acid bacteria were in there. That’s the same bacteria that are responsible for sauerkraut.” And it was like, “Oh, we made a sauerkraut of berries? Well, what else can we make a sauerkraut from?” And fifteen years later, we have a world-famous fermentation lab in the restaurant.

EMSo, where did you appear in this picture? When did you start becoming involved in the fermentation lab?

DZThat first inquiry led to a string of others. It led to: Well, if this is fermentation, what else is fermentation? Soy sauce is fermentation. How did the Japanese do that? What’s koji? What’s Aspergillus oryzae? How do they make miso? How do they make rice wine vinegar? How do you make vinegar? What else can you make vinegar from? And so on and so forth. All of a sudden, all of these doors led to more doors.

At the peak of all of these questions being asked, there was a very curious chef who basically ran the Nordic Food Lab, named Lars Williams—an American who had come via The Fat Duck and he was really pushing a lot of the fermentation projects forward. He had a very cheeky intern, Arielle Johnson, who had come from UC Davis, from the flavor chemistry program. They linked up, and a chef’s curiosity and stubbornness met a scientist’s kind of sober and measured view, and together the fermentation program at Noma took its next step. René tasked those two to build the first version of the fermentation lab beyond the Nordic Food Lab. That happened in the summer of 2014, which was just after I started as a cook in the restaurant.

That lab was built out of shipping containers, literally just boxes that came off of a Maersk ship that were chopped up. Patio doors were installed, and a very sketchy electrical system wired the whole thing together. But it did its job, and at the end of the day, it was the first and only one of its kind that anyone had ever seen in a fine dining restaurant. Lars and Arielle ran the lab and kind of took the program to the next level. All the while, I was downstairs drowning in mise en place, getting screamed at by sous chefs for not having my beets ready on time. And it always felt like an ivory tower: you would look over to the lab in the parking lot and be like, What are they doing up there? They give me a liter of this stuff every week and it tastes amazing, but I have no idea what’s going on.

After not very long at all, I was sat down one day after a service. I thought I was being reprimanded, and the head chef explained to me that at the behest of René and Lars, they wanted to move me into the fermentation lab. It was not because I was the fastest cook in the kitchen, it was because I was just a full-on smart ass. People would ask very innocuous questions about why things wouldn’t work, or what was the deal with this or that, and I was always the one with a very far-too-detailed scientific answer; and that just comes from my own curiosity and a lifelong love of science and self-education. And that’s what I brought to the table at Noma. I started as a cook, but like I said, after not too long I was moved into the lab. And even though I had no explicit interest in fermentation to the degree that Lars or Arielle did at the time that I joined them, it was very easy for me to catch on, because I could make the connections myself. And then the team really thrived.

EMAnd then just a few years later, you co-authored this really influential volume, The Noma Guide to Fermentation, which you worked on with René Redzepi. In the book, it seems like you’re definitely pushing the field of fermentation and experimenting with new techniques, but you’re also using and integrating methods and techniques that are thousands of years old.

DZAbsolutely.

EMYou talk about how preserving food and creating flavor have ancient roots in cultures all around the world. And it seems like the history of fermentation and the history of agriculture go hand in hand, that there is this embedded cultural and historical relationship present in fermentation—that it’s more than science, I’ve heard you say. Could you talk a little bit about that?

DZRené felt that we needed to write the book because there was this zeitgeist bubbling. He’s a very prescient man. He always has his finger on the pulse and has a knack for knowing what people are thinking, what people want, and then challenging those wants and thoughts himself. I remember the day that he burst into the lab, while Lars and I were researching a problem, and he said, “Guys, we need to write a book.” And we were like, Okay. And he was like, “I don’t want it to just be my voice.” And Lars said—cheekily, in hindsight—I think it’s time for me to pass the torch. He was like, “David has a great writing style.” And then it was just another thing on the bottom of my prep list for the day: write a book. It was tasked on me. I had made numerous contributions to the lab at that point, but I was working under the tutelage of Lars and Arielle. So it was on my shoulders to be the scribe of Noma and to put forth almost a decade’s worth of knowledge and investigations into the field, on top of my own personal thoughts and my own personal understanding of fermentation, and somehow make an amalgam of all that. And it ended up as the book that I saw you were reading.

It is a lot more than just a how-to book. It’s a lot more than just a cookbook. It is a book that strings a philosophy and an understanding of fermentation at a very deep level through recipes and explanations and histories and researchers. We can’t say that we invented these techniques. We just run with them and try to be creative with them. But we are not the new startup who has some sort of fancy new biotechnology on offer. What Noma does with fermentation is very deeply rooted in tradition, and very deeply rooted in an understanding of how these things worked in traditional societies and how these traditions have been preserved up until the present day.

But you’re absolutely right. There’s an amazing quote I love about fermentation from an Italian-American poet: “Fermentation and civilization are inseparable.” And it’s absolutely true. It is almost autopoietic. It was self-creating. People stumbled upon these techniques because it was the thing that kept them alive, and in keeping them alive, they kept the reason for their existence alive in the first place as well.

You know, if you have two batches of fruit sitting out in your cellar, and one of them for whatever reason had salt added to it—making a conducive environment for the propagation of lactic acid bacteria to keep that fruit edible longer compared to the batch that just rotted and molded and became disgusting and would poison you—you’d obviously be drawn to the thing that wouldn’t make you sick.

And in doing that, you would keep propagating—culturing, quite literally—both the microbes and the knowledge of the process that made it in the first place. You go back thousands of years to the Zagros Mountains in Iran, and you see the fermentation of wine for the first time. You go back to ancient Babylonia and Iran and Egypt, and you see the first instances of the fermentation of beer, and you wonder who was creative enough to do this. And I don’t think it was about creativity: I think it was about inevitability, because these microbes have always been around us. But the fact that we paired up—like wolves becoming man’s best friend at some point—it is really a fairy-tale story of two types of species finding the perfect symbiosis in each other.

EMWell, that leads to this term I’ve heard you use, which I found very intriguing— “microbial terroir”—and how fermented foods have a very distinct flavor profile that is dependent on the place where they are made—even if that’s just a few miles away or at a different altitude; and also, that the flavor changes dramatically depending on who’s making it, that relationship is very present on all sorts of levels.

DZAbsolutely. It absolutely is. If terroir is the minerality of the soil, of all the things that have lived before and died in that soil to make that soil what it is, microbial terroir is the exact same thing but on a microscopic level. We can’t truly understand how complex and how vast and how grand the microbial world really is. They are absolutely everywhere. We’ve found them kilometers deep in solid rock. We’ve found them in Antarctica, frozen into ice that’s tens of thousands of years old. We find them floating in the upper dredges of the atmosphere; we find them at the bottom of the ocean. It is truly a microbe’s world.

And the fact that the microbes here are not the same as the microbes in France, are not the same as the microbes in L.A., are not the same as the microbes in the Yukon—really does mean that there are pockets of distinction between these things. And when you make food with microbes, those things do show up and you do get that instance of terroir.

Later on in the book, I talk about hand taste. It comes from Korean kitchens: son-mat it’s called. Korean grandmothers will often speak about it. That’s the taste of something that’s made by hand, of the person that made it. And I equate that to microbial terroir. I equate that to all of the factors that could have contributed to making that population of bacteria on that person’s hand exactly what it was at that one time, that one day. And it is in some ways chaotic and beautiful, and in some ways intractable and irreplicable.

EMYou describe that there is this unique imprint that can never be found in factory-prepared foods, which is there when someone uses their hand and is engaged in an intimate way with the creation of food.

DZYeah.

EMBeautiful.

DZYeah, it is. It really is a beautiful thought. And when you do it, when you actually make these things for yourself and you start to taste it and you see it and you feel it—that hits home on a level that is hard to equate with a line in any text: it is something that you feel in the most fundamental of ways once you understand it.

EMOne thing that really struck me in reading your book were the layers of relationship present; because food plays such a powerful role in defining cultures and people’s relationship to place. And we almost take it for granted—because it’s so ubiquitous now how we can connect to place through food, whether we’re traveling or whether we’re just in a big city and being able to dive into a culture and its relationship to a place through its cuisine. And it’s perhaps the most accessible form of cultural, place-based expression out there. But it seems like fermentation almost takes us to a deeper level, where the connections between people, culture, place, and ecology all come together, including the microbial element. I’m curious to hear more about your exploration into those layers of relationship that you delved into.

My relationship to fermentation is kind of funny, because itcomes through Noma; and it comes through being a chef at Noma, a cook, a chef de partie, who has to make mise en place, and has to make it perfect, and has to make René Redzepi happy, and has to make his guests happy, and has to make something consistent. Fermentation never wants to be consistent. The idea that you can equate son-mat with chaos theory—that even the slightest permutation or difference between one scenario or another will lead to outsized results months down the line as the thing ages—that’s what fermentation is and always has been. The fact that we have different styles of fermented foods is that idea in the flesh: son-mat is, in some way, chaos theory lived out.

At Noma, it’s my job to make fermentation as perfect as possible every single time, which seems counterintuitive. It sometimes feels like trying to bash a square peg through a round hole. But when an unstoppable force meets an immovable object, it surrenders; and I do find a peace with just understanding that sometimes things don’t work out. But through my travels and through my research, with this understanding that, no, I am not in complete control—try as I might, and research as I might, and learn as I might to try and master this thing—it is, in some ways, beyond me and truly wild.

But one of the most amazing things that I saw when I traveled as a fermenter, especially when I was going on tour for the book and promoting it in the United States and Canada, was the amount of things that people would come and show me: things that they were proud of, things that they made that were, by any objective means, not that special, not revolutionary, but were so deeply personal to them because they had a hand in creating them. Tasting it, you would understand that; but you would also see that there was something more than just—Okay, this is pickled pluot. But it wasn’t just that. This was someone’s care; someone had watched this thing grow. Someone told me that it was their first time fermenting, and they sat and watched the brine change color for seven days, until they pulled it out and then added their mom’s favorite spice mix in at the end, and let it steep so that the pluots would be flavored. And you realize that all over the world, in every culture that’s ever existed, this is what fermentation has always been. There is not a civilization on Earth that does not ferment: from manioc being turned from poisonous to edible in the Peruvian Andes, to the yams that people eat in Papua New Guinea—one of the original centers of agricultural production—to beer in Babylonia, or all the cheeses of France, for all of their splendor and variation.

It is culture. You’re absolutely right. Food is culture, but fermentation is culture on a deeper level. And I love the idea that somehow, someway, these synonyms overlap—that “culture” and “culture” mean two different things to a biologist and an anthropologist, but in fermentation, they overlap completely.

EMDo you think one of the reasons why there has been this fermentation renaissance, this growth of amateur fermentors and interest among professional cooks, is that they’re trying to bridge this gap that’s so present now, collectively, that separates us from the sources of our food, and to reconnect on a deeper, philosophical level to nature and food and place and culture?

I absolutely do. To me it’s a bit ironic that such a rarefied—and I don’t want to say that Noma is elite; we try and keep prices low as much as we can and let everybody in—but Noma is a rarefied restaurant. It is a fine dining restaurant. And at the end of the day, we only serve about a hundred guests dinner. But I do find it ironic that it should come from a place like that. You know, the sentiment that you can return to nature and find other ways of knowing the world. People, whether they admit to it or not, want to in some way return to the things that got us here in the first place.

Growing up in the North American metropolis of Toronto, with six million people, the world that I was taught to want—that everyone could have that white picket fence, that everyone could grow, and prosper, and have 2.5 kids, and a dog, and a car, and a pension at the end of the day—that does not seem to be the way the world is unfolding. And many people are aware of that. Social unrest is one thing, but I think that on a personal level, where people feel like they can make actions, they do. And choosing to drink a kombucha over Coca-Cola is one of those things. It’s ironic that Coca-Cola and Pepsi are now producing kombucha, but hey, what are you gonna do.

But you’re absolutely right. People want to understand what got us here in the first place, like the practices of fermentation, things that have only ever existed in the homesteads of families up until the 1850s. As a kid, I had no idea how a pickle was made. I had no idea how the sauerkraut on my hotdog was made. I had no idea how my mom’s Caribbean hot sauces were put into a jar. These things were kept behind closed doors. They were veiled and they were kept secret, not on purpose, but you had to actively work to figure out how these things were produced.

Fermentation today is having this renaissance. It’s not undergoing a trend: it’s undergoing an understanding. People are realizing this was always a power that was in our hands. These things are there, waiting to be used, if only you know how. And that’s the beauty of it. That’s why I think the Noma Guide to Fermentation struck such a chord, because it showed people that this is actually very easy to do, and it’s not something to be afraid of. And it’s not only the Pickle Boy brand sour dill: it’s everything in the world that you could possibly imagine, if only you have that little bit of knowledge and the will to do it. I’m excited for what’s to come, because you see the fervor, and you see people’s enthusiasm; you see people connect to food that they made. To ferment something is to invest not only in a project, but in your own future. That’s what it was. That’s why it kept people alive. And I think that’s a value that no company could ever sell someone: it’s something that has to be undertaken yourself. And people get that.

EMYou’ve talked a lot about how, over the next fifty years, the way we eat is going to dramatically change. And as you said of the next hundred years, we’re barreling into this very uncertain future as we deal with the impacts of climate breakdown and everything that comes with that—how we’ll have much less fish or seafood in the oceans and the rivers, and the access to ingredients will change. So how do you, as a chef and a pioneer in this world of fermentation, see our eating habits changing?

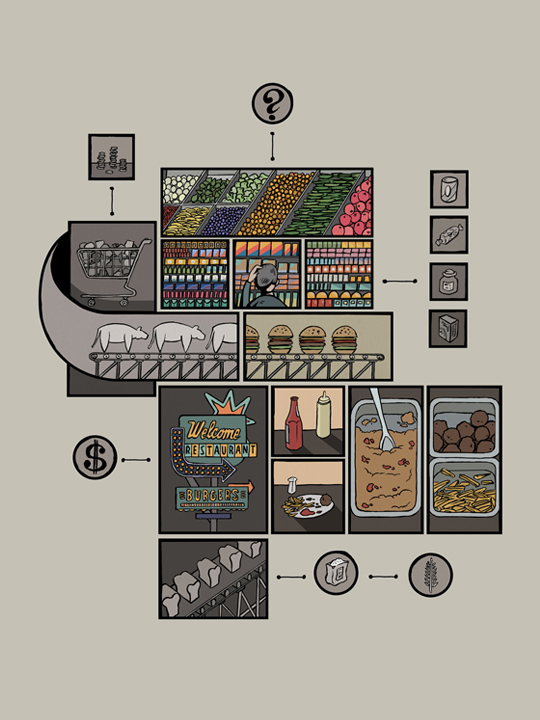

DZHow do I see our eating habits changing? I think that unless we make active choices at a policy level, at a governmental level, about how giant multinational corporations are allowed to operate and are allowed to produce people’s food, the change that will happen to people’s diets will be reactionary when crops fail and when things aren’t on grocery store shelves that people expect to be there.

People can take minor actions to engage in community-based agriculture: start cooperative farms, urban gardens, or rooftop gardens. These are steps toward understanding processes and giving yourself training on how to produce your own food. But it’s also a bit naive to think that all of these little pockets could ever make up the amount of calories that go to feed the entirety of every developed nation and every underdeveloped nation as well. At the end of the day, those calories come from giant farms. And there’s a lot of people who have no interest in committing to community-based agriculture or participating in a lot of the things that enthusiasts today are championing and trumpeting.

And that leads me to believe that for all of everyone’s best intentions—and I’m not trying to be defeatist here. I’m not trying to be a fatalist and be like, “It’s all lost and there’s no hope.” That’s not what I’m saying. But I do have to take a pragmatist’s view and say that the change will be reactionary, because companies will go forward as if everything is fine until the day it’s not. There are all sorts of reasons why the food system is more fragile than it needs to be. People will [have to] turn to things that they aren’t normally used to eating. If I were to ask my mom, “Hey if you went to the grocery store and cornflakes weren’t there, what would you get instead?” I don’t think she would have an answer.

I might have an answer. But I would only have an answer because I’ve worked at Noma for five years, and I have a vegetable literacy. I can walk out into a field, look around, and read the landscape, and say, “Oh, I could harvest that root. I could take these plants and ferment them. I could climb up that tree and pick these plums and salt them and make sure that they would last and not spoil.”

I know that because I have an education in it. The vast majority of people don’t know that, because they don’t have an education in those fields; and they haven’t needed to. Big corporations don’t make money because they share the knowledge of how to not use what they produce. In some ways, ignorance is profitable.

And it worries me that people will be ill-prepared or ill-suited to adapt in a time of need when push comes to shove. It’s a scary thought, but it’s one that I’m hopeful will also scare people into acting, and scare people into learning, and scare people—more people, a critical mass of people—into being able to at least spread and disseminate knowledge should things go bad, should push come to shove, should a deus ex machina of technological or biological origin not manifest itself by 2050. I just hope that there are enough people who will have taken the initiative to understand how the world works to know what to do in a time of need. It’s not about prepping. It’s not about stockpiling weapons and preserves and canned goods for the end-times. It’s about being able to adapt and being prepared with the knowledge that we have at our disposal today to make sure that we’ll be okay tomorrow.

EMThe practice of fermentation has always been intimately tied to the seasons. Preserving seasonal food during times of abundance as a means of survival during the winter and as a practical skill for overcoming what is unknown, which has always been there in civilization: Will the crops fail in the future? Or will things change? Now obviously, as you describe, the unknown is in the uncertainty of our food system for the coming years. But food preservation has also been an expression of the season itself, an expression of joy and wonder through the preservation of seasonal ingredients at their peak, which is something that, as I understand, Noma and your work at the fermentation lab really focuses on too: how to capture that wonder and joy and expression of abundance in the summer seasons in the food that you eat throughout the year. I’m curious what that’s been like for you personally. How has your relationship or understanding of the seasons changed since you’ve been doing this work at the fermentation lab?

DZIt has become intimate, you could say. When I was twenty years old, I had a girlfriend from Berkeley, California. I was living in Vancouver, Canada, at the time, and she was studying at the local university. I asked her, Why’d you come here? Why didn’t you just stay in Cali? She said, “I came here because I wanted to experience the seasons. I wanted to feel what fall felt like. I wanted to see snow, and know it.” So, I guess not everyone has an intimate relationship to the seasons. And with the way that the food system is built today, you can get white asparagus in January, February, March, April, May, June, July, August, September, October, November—It truly is a global net that wraps itself around the world. The way Noma works, especially the way Noma 2.0 works in our new installation, working hyper-seasonally, you have this deeply intuitive knowledge of the seasons. When you see the foragers bring in the first ceps, you feel a chill in the air before it’s actually there. When you see the first ripe mirabelle plums dropped from the tree, you’re like, “Okay guys, get ready in the lab. We’re about to go into full preservation mode.” Because you know that you have to store these things at their best so that you can use them in January on the seafood menu when there’s nothing else outside; and it’s on us to make that menu exciting.

From a practical point of view, what it actually takes to do my job to capture nature at its peak, at its finest, means nudging my foragers and saying, “No these plums are not ripe enough. You should have left them on the tree. I’m sending these back. Go out tomorrow and pick me five kilos of plums from the trees next to that.” It is something that kind of gets inside you. And the way I talk about plant literacy—being able to walk out into a field and read the landscape, and say, okay, this is edible, that’s edible, and recognize these things. There’s also a seasonal literacy. There’s a literacy to landscapes. We often hear foragers talk about this when they go into the wild. They know that they’re not looking for a plant necessarily; they’re not looking for the shape of a leaf. They’re looking for an ecotope or a biotope. They’re looking for a type of nature that has shade, or grass, or running water through a stream. If they know they’re looking for a plant that exists in dry soil, they’ll look up a hill, intuitively. And these are things that you only really truly understand when you do these things again and again and again, and you learn by rote.

But this is the fascinating thing: for all the explanations of what makes humans human—for every anthropologist that has some pet theory about fire, or wading through water, or walking in the African savanna—the one that I believe more than any other is that the human brain developed its ability to categorize the world because we had to forage for our survival, because we had to make sense of the world more than other animals did. And it served our benefit to be able to name and catalog plants.

I mean, every cave painting on Earth talks about hunting and gathering, and keeping people alive through food. That’s something that’s incredibly important. I think it would be worth it if, instead of being taught civics class in high school, people spent six months in the wilderness learning how to keep themselves alive. I think that’s more important to someone’s long-term well-being, both mental and physical, than a course on what American president was doing what in 1792.

EMHow has this affected your relationship to time? I’ve actually done a lot of thinking about this. Because I live in California, I don’t experience the seasons in the same way that you do in Copenhagen or in Toronto. We don’t have snow, but we have changes of seasons that force you to think about time. Because when you’re in peak summer and it’s hot, you’re present in that moment; and for that moment in time, it’s hot. And you know it’s not going to last, because you’re moving into fall—in the same way that fall has a crispness in the air that’s not going to last as you move into winter. I’m curious how your relationship to time has shifted, or changed, or deepened through this work.

DZIt’s funny, because the work is one thing, but working at Noma is another. In some ways, I feel like my five and a half years at Noma has felt like fifteen, and also gone by like one. But my relationship to time is a tricky one. Your analogy to rhythms is on the nose though, I will say that. I read a lot of books that don’t pertain at all to food, or foraging, or fermentation, or gastronomy. And sometimes a lot of it has to do with economics. If you find a smart economist, the first thing they’ll say is that most economics is bullshit. But a good one will tell you that nothing ever lasts, that things can’t just continue perpetually forever; and that in good times you should prepare for the bad, and in bad times you should also prepare for the good. And it is the same sentiment: once you understand intuitively that seasons give way constantly, that nature has rhythms, and that everything kind of follows a sine wave, you begin to realize that everything in life is kind of following that same trend, that nothing just gains perpetually—not plants, not vegetables, not trees, not people, not relationships, not time. You’re right on that.

EMOver the last few years, it seems like there have been some major trends developing in food culture, towards local food, slow food, and the idea of eating healthy food in high-end restaurants like Noma. In some ways, it seems like this is an evolution of the organic and sustainable food movements, and one that fermentation is playing an active part in. Do you think this is speaking to a deeper need that people have?

DZIt is—it’s a rhythm, again. Like, if something dominates, an alternative will present itself by people who maybe are contrarians, by people who maybe see things differently, but always by people who think, for whatever reason, that there could be another way. And I don’t think that it was ever ill-guided at all to start the slow food movement, or to start a restaurant that focused on what grew where it was and chose not to import ingredients; or to start a restaurant based around ferments, like Baroo in L.A., which is now, sadly, closed.

But I also kind of champion contrarians, because they do fill those needs for people, and they do offer up alternatives when they see that there is a dominating type. They kind of find another way and give people a crack, or a little opening, to explore should they so choose. It’s not always easy to be the little guy in the face of big agriculture or big business. But at the same time, it’s also really funny when you see corporations like Coca-Cola clueing into kombucha and being like, “Oh, wait guys, we’re late for the party. We should hop on this bandwagon.” And I don’t necessarily think that that’s a bad thing. But yes, it does fill a need: a need for difference.

EMThis leads to my next question, which is how do you see the role of restaurants like Noma, and chefs like you and René, in pushing global food culture? Because it seems like now, more than ever, you’re wielding a great deal of influence on other chefs and restaurants, and also on what ends up on supermarket shelves and produce aisles. What role do you think food influencers like yourself should play? What’s the responsibility you have with all that power?

DZIt’s a huge responsibility. And it’s funny, sometimes people call me out on Instagram if I post a project that I was doing with meat, and they’ll say this exact thing, like, “You have a responsibility. You shouldn’t be posting meat.” It was a wild animal; it’s not like a factory-farmed cow or something. But you get that sentiment. Maybe sometimes people are out of place, but you get the sentiment that people also expect responsible actions from people in power and are comforted by it when they see it.

But you’re absolutely right. Noma, as an entity—which is more than just one chef, is more than René, even though he is the impeller, and the driving force, and the man who started it all. But in Copenhagen twelve years ago, you couldn’t buy a skyr, an Icelandic fermented milk, in a grocery store, and today you can. You couldn’t get sea buckthorn sodas at a coffee shop, and today you can. There’s all sorts of things that Noma has cooked with and kind of made people aware of that then went on to be popularized and consumed.

Now it’s one thing for a business to—I’m obsessed with this analogy of stealing fire—it’s one thing for a business to steal fire from some of Noma’s ideas and ideologies, but it’s another thing to just get someone to do something that has no economic impact and send them foraging for their lunch on a weekend. That’s powerful. [Having no impact is] the point: it has no impact if you know how to forage properly, if you know how to take from the Earth without destroying it, if you know how to feed yourself without causing any harm or any transportation costs in a system: that’s real impact.

If someone gives you a soapbox, just use it for good. And maybe people will call us hypocrites, because the majority of our clients fly in to Noma. The majority of our clients are affluent enough to be able to fly in and spend as much money as you have to for a meal at Noma. But I think that the amount of people that we inspire with our philosophies, and through our writings and books and social media stories, and everything we do to just try and make the natural world that much more exciting, is great. So I think, yes, there is a responsibility for anyone in power to do the best they can to spread a word of goodwill. But I also think that there’s a responsibility on the listeners’ side to put their attention where it counts the most, and to get excited about things that matter on a deep level, not just a superficial one.

EMWould you say that you, and René, and all the folks at Noma are consciously pushing an agenda that’s geared toward more holistic and conscious eating, or is it a natural evolution of having to create a Nordic cuisine?

DZI think those two things are inseparable to René. I really do. I think it is his fiber. I think he had an amazing combination of an upbringing in Macedonia—basically living on farmland for the summers—and then Denmark, which is also a kind of funny place to grow up, especially through the ’80s and ’90s. It’s definitely not what it was back then: it’s really blossomed as a first world nation. I think that that agenda and what he strives for are no different, and I think that everyone who works for him is so attracted to and empowered by those ideas and ideals that we’re all just trying to share in it.

Some of the most talented people I’ve ever known in this industry work within those walls. Not just the chefs, but the front of house, the servers, the people who have championed and made an entire cottage industry out of natural wine. It’s remarkable to see the passion that flows out of that restaurant. And it’s not about pushing an agenda: it’s like lived truth. That’s what it is. Noma’s ideals only ever grow and become more Noma. And that is as true for the new restaurant as it was for the restaurant that was just trying to get noticed twelve or thirteen years ago; and I don’t think it’s going to stop anytime soon.

EMYou’ve lived in Copenhagen for five years now. How has your relationship to Copenhagen developed and changed over the years? You lived in Toronto for many years. You’re from Canada. But you didn’t ferment there; you didn’t have this relationship with microbial terroir and seasonal ingredients in the same way, or with foraging—this connection to place that you’ve described. How has your relationship with Copenhagen changed through this work?

DZMy girlfriend thinks it’s funny, but we can’t go for a walk in a park without me bending down and picking up the ground and putting it in my mouth. Now, that’s how you know a Noma chef is a Noma chef. He’s outside and just eating whatever’s around him; just being like, how does this taste? That’s really funny, but I wish more people understood that curiosity. Because once it’s in you, you can’t get it out. And once you do it, you just won’t stop doing it, because there’s no distinction between outside and inside.

I don’t know what it is about this North American germaphobia, where things that come in prepackaged, styrofoam, plastic-wrapped containers that you bought from a sterile, neon-lit, white, freezer section are okay to eat, but your mother would smack you if you put an insect in your mouth. It’s weird that there is this mentality, and there is this apprehension about experiencing the world unless it’s prepackaged and boxed off, and you’re going to a campsite. Walk for a few hours and you’ll be in nature, you’ll be in wilderness. Copenhagen’s small enough to afford you that; maybe L.A. isn’t, but if you try hard enough, anyone can do that. And that’s something that I think everyone deserves to have in their mind—that you can always make an effort, walk in a direction, and find nature and just bask in it; because it is so much better than a screen, in my opinion. And that’s something that Noma’s taught me: working at Noma, and being in Copenhagen, and just the comfort that Danes have about existing, has definitely gotten me to see the natural world a little differently, and to break down the barriers between the other and the self, much more so than I could have known if I’d stayed in North America and kept working in big metropolises like Vancouver or Toronto.

EMDavid, it’s been an absolute pleasure speaking with you. Thank you so much for joining us.

DZThank you. It’s been amazing to get to talk about some of this stuff with you.