Jay Griffiths is the author of Anarchipelago; Pip Pip: A Sideways Look at Time, winner of the Barnes and Noble Discover Award; Wild: An Elemental Journey, winner of the Orion Book Award and shortlisted for the Orwell Prize and the World Book Day Award; and A Love Letter from a Stray Moon. She broadcasts widely on BBC Radio and her writing has appeared in the Guardian, Orion, Lapham’s Quarterly, the Ecologist, Dark Mountain, and more.

Studio Airport, founded by Bram Broerse and Maurits Wouters, is an interdisciplinary design studio that ventures out into the cultural ether to forage for anomalies, creating work that spans art, culture, science, and ecology. In addition to Emergence Magazine, their creative partners include the Design Museum, See All This Art Magazine, Slowness, Normal Phenomena of Life, and Sapiens Magazine. They serve as master tutors at the Design Academy Eindhoven and were recognized as European Agency of the Year 2024 by the EDA.

Marveling at worms, fungi, and the pioneering water bear, Jay Griffiths brings our attention to what dwells beneath our feet, inviting us to remember that soil is what turns the Earth’s barren rock into the riotous life we know.

The earth of my garden is the heart of my home. All summer, my garden is the hub of my life: I read here, eat here, talk here, drink here. My friends spill out of the house merrily onto the grass, with candles and drinks. There are other characters here too: the rain, the wind and sun. The rain is sometimes gentle, sometimes fierce; the wind is eloquent and sometimes angry; the sun sometimes soft but often strong. Beneath them all, the soil, shyest of all. The garden links all these elements: earth, air, fire, and water.

Just so, soil (the pedosphere) is at the heart of the biosphere. As the English diarist and scientist John Evelyn wrote of soil in Terra (1675): “the best, and sweetest, [is] enriched with all that the Air, Dews, Showers, and Celestial Influences can contribute to it.” It uniquely intersects with the water of the hydrosphere, the air of the atmosphere, and the rock of the lithosphere.

Soil is the source of our sustenance during our lifetimes. Harvests upon harvests; sheaves of corn piled together reaching the skies; mountains of apricots; grapes a mile deep: the soil provides sheer bounty, plenty, and abundance. This is the overground beneficence of Earth’s soil, but it holds subterranean beauties as well. Sand, silt, and clay particles combine to form soil, and the clay carries a surface electric charge. Good earth contains air too, pores for roots and water. The colors of soil include oxisols, the tawny color most often found in tropical rainforests; spodosols, the gray-yellow of boreal forests and heathlands; ultisols, which can be almost purplish, pale orange, low yellow, or red; and vertisols, the earth of savanna or woodlands, which may be gray, brown, or deep, deep black, known as the black earths in Australia, or the black cotton soils in East Africa.

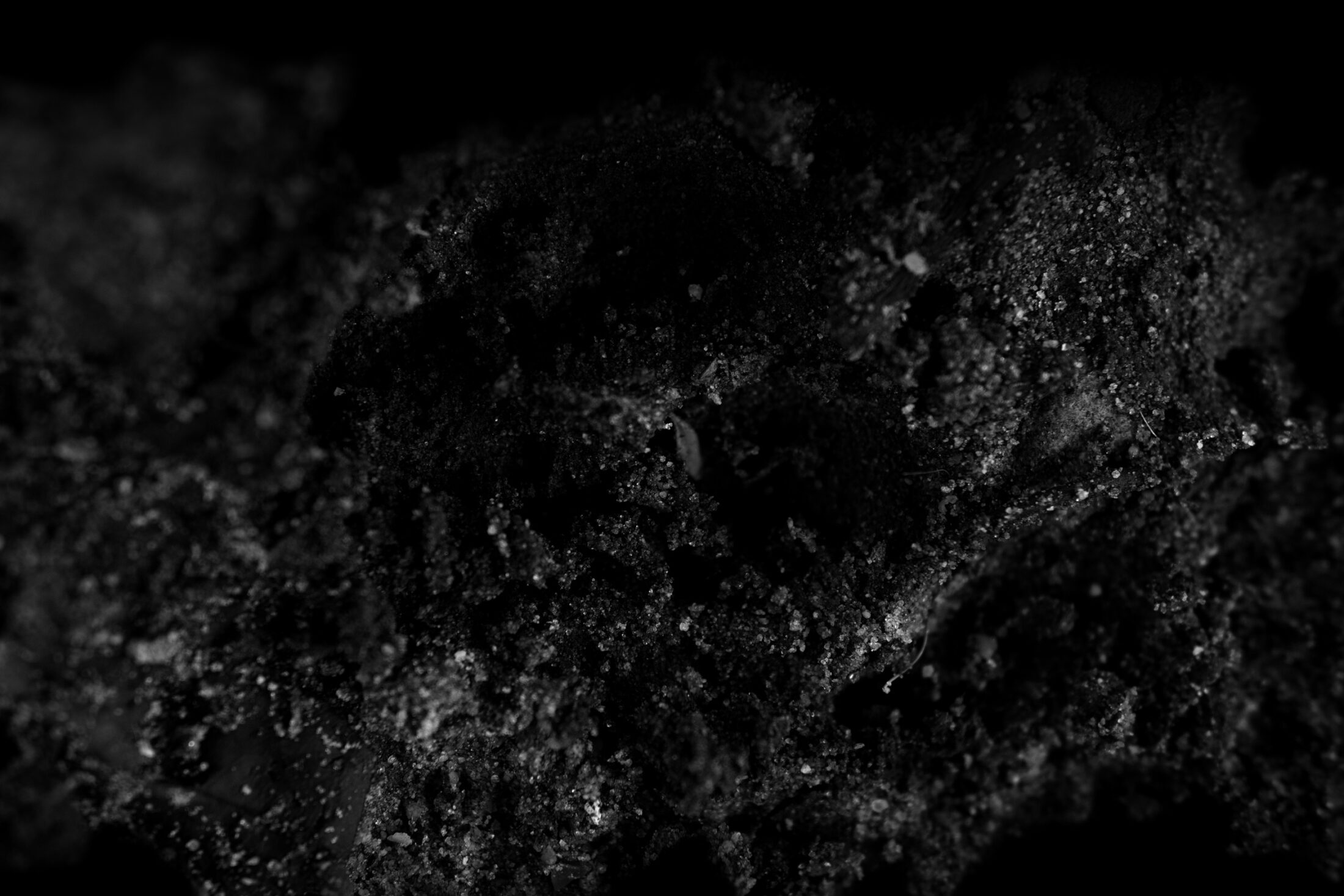

Soil is usually illustrated in the vertical and described as if you are digging downward through, first, the humus or topsoil and then down further into the subsoil and on down to the bedrock. These layers are called “soil horizons”: when we look down, we see the horizon that gives us food. One soil horizon is called the “eluviated horizon,” a phrase to conjure with: eluviated, rejuvenated, alleviated with the movement of rainfall, a transporting of matter further downward. All this, when you look down into darkness.

Underfoot, there are colonies of microorganisms, countless and complex catalysts in symbiosis, in a lively world tingling with life. More than half of all terrestrial biodiversity is in the soil. Fungus, specifically mycelium, and worms, mites, and bacteria create life’s fertility and regeneration, and topsoil is created by creatures that can break down leaf litter and wood into the richness of humus, cycling food from deadness to make thriving life.

Who else dwells here below? Rotifers, their tails turning like wheels. Protozoa. Amoebae. Nematodes or roundworms, some feeding on fungi and some being food for fungi and bacteria. (It’s all feast down here.) There are forty thousand named species of mite. Here, too, there is the hardy tardigrade, better known by its endearing moniker, the water bear, champion of sheer survival; and also the glorious Collembola, or springtail, that can jump a hundred times its own length. These miniature shapeshifting jesters can alter their size and shape rapidly if they need to. And they have eye patches. While some Collembola live on the top of Mount Everest, they are also the deepest land creatures on the planet, one species found in a cave in the Western Caucasus at a depth of 1,980 meters underground. They were coaxed out (reports Andy Murray, Collembola-lover, writer, macro-photographer, musician, juggler, and archaeologist) with cheese.

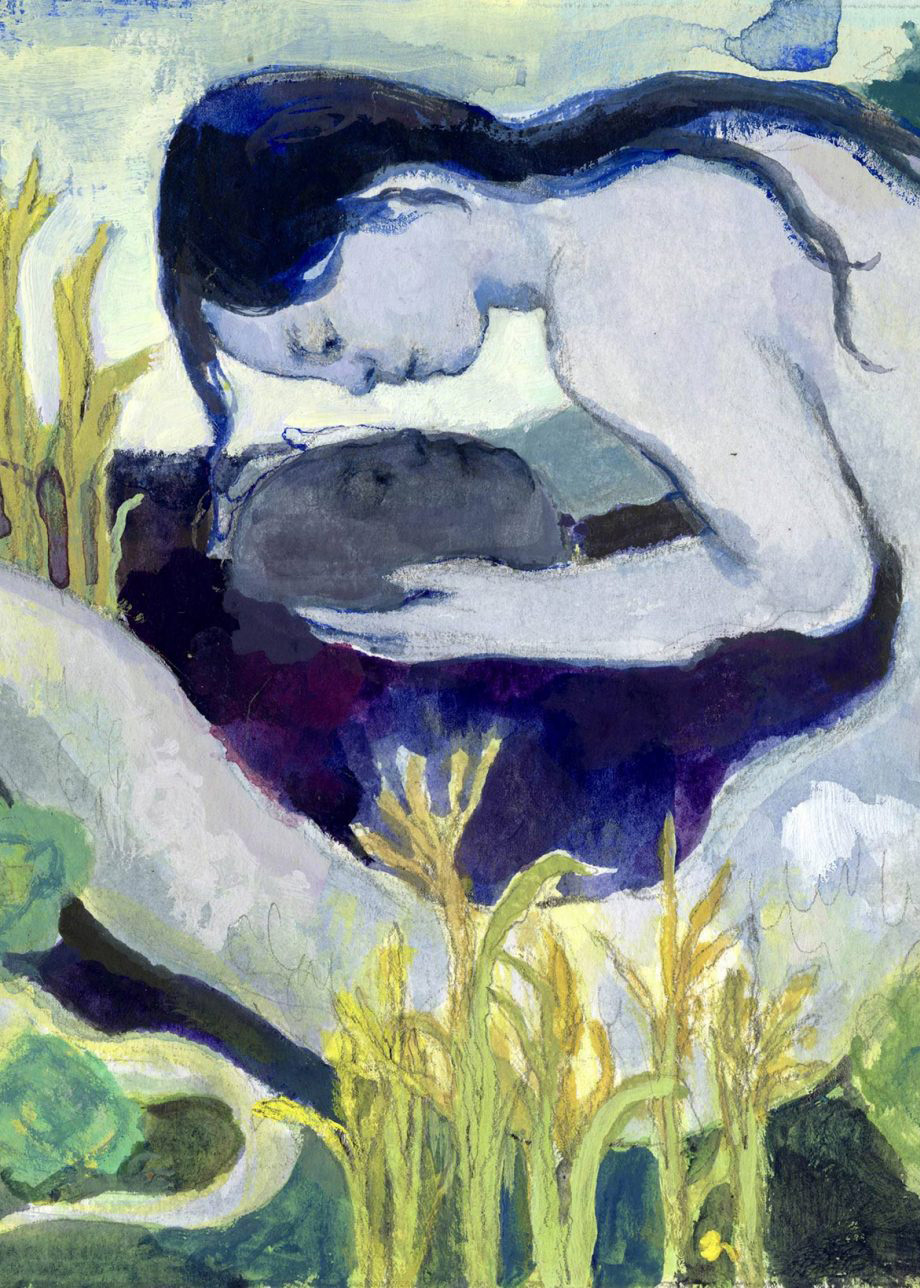

The most visible and well known of the soil dwellers is the worm. I love the worms in my garden, the wriggly, glistening worms that work the soil that sustains the trees that grow the apples that feed me. The tumult of worms in the compost bin are the ones I love most of all, though sometimes I worry that their effervescence is due to the coffee grinds. If I dig over the compost, I want to apologize to the worms first, and offer a prayer of gratitude to them for their quiet ceaseless work. They make the soil soft, silky, supple, and moist, and its fresh, fertile earth-scent is heaven sent.

In Darwin’s last work, The Formation of Vegetable Mould, Through the Actions of Worms, he sought to demonstrate that worms have mind. Worms make burrows and plug the openings with leaves, and this activity, he saw, was neither random nor wholly instinctive; and in that space between, a form of mindedness can be inferred. Worms, he found, formed judgments about the different shapes of leaves, even the leaves of a plant with which they were unfamiliar: he witnessed the way they made decisions about how to best drag a leaf by feeling it carefully and judging the right maneuver.

These unacknowledged makers of the earth, sensitive to touch like the tip of your tongue, are quiet gardeners of delirious fecundity. The quiet ones, quietly making life possible, the ones who shun the spotlights, the unstarry ones on whose lovely liquid glistening—true brilliance—the world turns.

In the soil of my garden, under a rock, one of my cats is buried, the cat whose death left me inconsolable. Soil is the dark forever where we go after death, earth to earth and ashes to ashes: where our existence ends. It is also where we come from, creatures of earth and fed by it, our brief lives poised between two long eternities of soil.

I have watched eternity happening, rolling and unrolling time, turning it forwards. I have heard the little rattles of dead leaves, light as rain, as earthworms eat and cast leaf litter to create soil, acting in sweet complicity with both life and death. I have seen roundworms pass for shooting stars in shimmering slowness in the other dark beneath me.

Life moves like this: creating, linking, making, and turning. It is soil that turns the Earth’s barren rock into the riotous life we know. Wheels on wheels of life in this unique planet wheeling its green-blue feast through the starving blackness. Soil that turns past into future, turns age into youth. Viriditas, the force of green life, grows out of the dark and turning earth, and worms are the artists of the turning world, returning vitality to it. Worm-shine licks the earth, tickling it to harvests and intricately re-thinking the soil into a different cast.

The word “turn” means to transform, but its root (from Proto-Indo-European tere-) is to rub. The worm, softly rubbing through terra mater, passing through the soil and passing the soil through itself, turns soil into bright actuality, transforming the dark and turning earth and turning death back to life, the lovely holy worm.

It takes a certain cast of mind to find mind under the soles of our feet; to be receptive to the possibility of intelligence where it is least expected, to be willing to attend so closely, to listen so deeply earthwards: it takes a kneeling humility, and in that kneeling posture, the capacity to be awed by an unexpected elder. Fungi is one billion years old. Through threads of fungi, a whole forest is connected and aware, and by means of these connections the network responds differently to the presence of different creatures. Tree roots spread out like curiosity, linking with mycorrhizal fungi in symbiotic relationship, feeding each other with information, messages from the underground, suggesting, hinting, telling, guiding, warning, giving, and giving deeply, feeding the soil-mind with the oldest and kindest wisdom. This network connects almost all trees and plants and is both gigantic and intimate, ancient and immediate.

Many of us have been wonderstruck at the discovery of mindedness within the earth and between trees, sensitive, exploratory, and communicative. Mind recognizes mindedness. Here, there are message threads. Communication lines. Information superhighways. Knowledge paths. We humans know linguistically that thought is well represented by linking filaments—including the tendril of this sentence, through which my mind flickers briefly in yours—and soil makes rhymes for our minds, underground.

In fact, the deeper we dig, the more life we find. Within the subterranean world, over five kilometers deep, twenty-seven thousand fathoms down, there exists a rich ecosystem, twice the size of all the world’s oceans, teeming with micro-organisms, hundreds of times the combined weight of all humans. The Earth has more life than previously thought. It is a discovery which takes my breath away, hushes me to listen in to its deep song. It alters my very footsteps: tread softly for we tread on something subtle, ancient, and slow. Some organisms here can live for thousands of years, part of the unfathomably slow time of geology.

Modernity isn’t good at slowness. It demands instant gratification and grabs “right now.” It prefers shallow time to deep time and is impatient with the easy languorous times of nature. All time lies below us in the soil: the deep past is there, the present is fed there, and the future could be nourished there. Time is fed by soil.

In the slow time of nature, it takes about a thousand years for an inch of topsoil to form (with no one watching). It also takes about a thousand years for a civilization to live and die (with no one really noticing why). Why did so many unrelated civilizations all last about a thousand years, asks David R. Montgomery in Dirt: The Erosion of Civilizations. Because it took about that length of time to strip the topsoil. In his book, Montgomery explores the stories of some of these civilizations, from their seedling beginnings to their thrivings and then their witherings.

Tread softly for we tread on something subtle, ancient, and slow.

When Romulus founded Rome in about 750 BC, the soil was richly fertile for a wide variety of food: olives, figs, and grapes; peaches, apples, and pears; almonds, walnuts, and chestnuts. The Romans knew how much they needed the land’s nourishment, both literally and conceptually. It was they who called Earth “terra mater,” and many prominent Roman families took names of vegetables in earthy pride: the family name Fabius, for example—as in the Roman statesman and general Quintus Fabius Maximus—is from the Latin faba, bean. But some philosophers showed less deference to nature, proclaiming that human technical skill could provide solutions to any problem: the ambition of agriculture was to engineer “a second world within the world of nature,” according to Cicero, whose name comes from cicer, meaning chickpea.

Gradually, the soil of Rome was pressured to produce more and more. Roman agronomists advocated plowing—sometimes many times in a yearly cycle—in order to save labor. The plowing, though, led to erosion: after plowing, when there was heavy rainfall, soil was lost, slowly but certainly. Towns that once flourished declined and their populations left. Then the Roman Empire could only feed its people by conquering new territory where there was still enough soil.

“Rome didn’t so much collapse as it crumbled, wearing away as erosion sapped the productivity of its homeland,” writes Montgomery. More than an inch per century vanished. In any one year, this amount of soil loss would have been almost beneath notice: if the topsoil had been between six inches and a foot deep, then it would have taken almost a thousand years for the Roman heartland to lose its topsoil. The evidence of erosion was poignantly noted by geologist Sheldon Judson in the 1960s: A road out of Rome, the Via Prenestina, protruded several feet above the soil on which it had been built. The foundations of a water tank, built around 150 CE, were now exposed, like bones of a civilization sticking up out of the ground where the topsoil is gone. “We overcrowd the world. The elements can hardly support us. Our wants increase and our demands are keener, while Nature cannot bear us,” wrote author Tertullian around 200 CE.

Repeatedly, civilizations have died because they did not look after the soil on which they depended. Today, the thick jungles of northern Guatemala hide a secret world: thousands of ancient structures, homes, canals, and pyramids of Mayan civilization. Across the jungles of Mexico and Honduras, the story is the same: tantalizing ruins, eloquent of a lost culture, asleep in the tangled green. Early Mayan culture included slash-and-burn agriculture, where people would use the land for its brief fertility and then move on to another area. But when the great Mayan cities were built, people stayed in one place and began farming the land to exhaustion. An increasingly fragile soil couldn’t feed an increasingly large population, and soil erosion peaked just as the population crashed and the Mayan civilization collapsed, about 900 CE.

The Fertile Crescent, the cradle of the Mesopotamian civilizations in what is now Iraq, was extensively farmed and over-irrigated to the point that the earth turned white with salt, which rendered the land infertile and desolate. Rome famously destroyed Carthage, as the story goes, by deliberately salting the earth: the people of the Fertile Crescent did the same to themselves by accident.

In northern China, forest land was stripped and cleared, and the topsoil was destroyed. This resulted in a massive famine that was a major factor in the deaths of half a million people in 1920–21. The land was little more than dirt, barely dust in the wind, and some twenty million people were scraping the soil for anything at all that would grow. The topsoil was gradually lost: the inhabitants had starved themselves, but “just too slowly for them to notice,” writes Montgomery.

How do we walk the earth? How do our feet touch the pedosphere? Whereas nomadism and hunting and gathering stepped lightly across the land, farming began to tread heavily. Agricultural communities settled and fed on the abundance of the earth until populations bloomed, green and thriving like plants from the soil. Then, exhausting the earth, over and over again, cultures withered and died. From ancient Greece to Egypt, the cycle repeats: over-use and depletion, erosion, exhaustion, and loss.

“Upon this handful of soil our survival depends,” notes a Sanskrit text from about 1500 BC: “Husband it and it will grow our food, our fuel and our shelter and surround us with beauty. Abuse it and the soil will collapse and die, taking humanity with it.”

William Blake wrote of seeing a world in a grain of sand, holding “Infinity in the palm of your hand.” It speaks to me of infinite life both on Earth and in earth, the ceaseless abundance within a speck of soil, the infinity of life, from seed to bud to flower to seed, wheeling on through aeons. It suggests the unbreakable cycle, the unending and unendable nature of life, creating infinity from within itself.

Smaller than even a grain of sand is the water bear, a pioneer who inhabits new environments so that other invertebrates can then make themselves at home. They are found in almost every habitat on Earth, from tropical rainforests to the Antarctic, from mountain peaks to sea floors. This tiny creature, visible only through magnification, is also called the moss piglet, as it lives in films of water in mosses and lichens as well as sand dunes, soil, and leaf litter.

Water bears, so-called for their barreling rolling gait, are more properly known as tardigrades, literally “slow-steppers”: not for them the speed of a rocket launch. Slow and ancient, they are thought to be some 530 million years old. About half a millimeter in length, they are short and chubby with eight legs, and many have pigment-cup eyes and sensory bristles. They can survive cold at minus 272 degrees Celsius (520°F) and heat at over 150 degrees Celsius (300°F). They can go ten years without water and thirty years without food, drying out until they are only about 3 percent water. (When they get water, they rehydrate and reproduce.) They can withstand pressure up to 1,200 times atmospheric pressure and can suspend their metabolism, entering “cryptobiosis.” They have survived Earth’s first five mass extinctions and are the first known animal to survive in outer space—on the outside of a space rocket.

It seems like a parable. Yes, the water bears survived exposure to the vacuum of outer space without the protection of atmosphere, but they did so by entering their own death-zone. As soon as they arrived back on Earth, they rehydrated in delirious relief with the water of life, and then reproduced. Every scrap of life is eager to thrive in the one place where it can, living between two skins: the tissue of soil and the delicate skein of the ozone layer. Here is where life flourishes, in or on the soil, the source of our nourishing in every sense.

It is the soil that feeds the world, the ultimate giver of food. This is the one thing that gives and gives and gives: food year after year in the most ordinary miracle. So ordinary and abundant, we take it for granted. The soil is the ground for every harvest, the seedbed for every crop.

Yet only sixty harvests are left before soils are too degraded to feed the projected world population, the United Nations has warned. The forecasts vary: some say we have a hundred harvests and some say thirty. Inherent to the idea of harvest is that even if it fluctuates, it will always happen. Harvest means abundance in time, as certain as evening, as perennial as autumn, eternity on Earth. The very idea of harvest suggests that time and life will continue, everlastingly. It is grotesque to imagine this limitlessness made finite: not just wrong but warped and ugly.

Soil is abused, poisoned with chemical fertilizers, fungicides, herbicides, and pesticides, leading to a collapse of soil health, the killing of microbiota. Intensive farming dims the vibrancy of the underground world; soil loses its organic components. Deforestation leads to soil erosion, and plowing can damage the structure of soil, while the sheer weight of giant tractors compacts the soil and crushes the tiny dwellers within it.

Among these dwellers are the earthworms, who increase food crop yield by an average 25 percent and are known to be essential for soil fertility. An average field may contain two million earthworms, and their abundance indicates the health of the soil. They eat and cast, eat and cast, and their casts are beautiful and moist, shining like diligence. But within three weeks of glyphosate application, their casting activity nearly disappears, as a study from the University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences in Vienna has shown. Their reproductive activity falls by more than half. The overuse of herbicides has resulted in herbicide-resistant plants that lead farmers to reach for more chemical “cures,” in a vicious circle that only deepens the imbalance.

The life within the soil is essential to bringing forth life from it. Reproductive activity helps invigorate the soil. Soil contains life and creates it, not only directly with agriculture but also in the larger realm of the global climate crisis, as soil can absorb and hold carbon. It is one of the most ancient relationships on our planet. Soil holds more carbon than all of Earth’s plant life and atmosphere combined, and it can hold more depending on the life within it. In devastated soils or with the excessive use of synthetic fertilizers, the balance switches from absorbing carbon to releasing it. With soil degradation, the climate crisis accelerates and then land is further damaged. The relationship between carbon and soil is so entwined that the climate crisis cannot be redressed while the soil continues to be devastated. It is that simple and that vital.

About a third of the world’s soil—approximately the surface area of Mexico and the USA—is thought to have been degraded over the last forty years. When soil is degraded, it is more likely to suffer erosion from wind and rain. While Europe loses nine million metric tons of soil each year, the World Wildlife Fund says that half of the world’s topsoil has been lost in the last 150 years. Because soil is created so slowly, it is in effect a finite resource.

We know what happens. The Great Plains in the United States were once famous for their fertile prairie soil, but the area was first over-grazed and then over-plowed, the indigenous grasses cleared. In a period of drought lasting eight years in the 1930s, storm winds created “black blizzards,” clouds of dirt. It was as if the soil simply had no strength. Exhausted and depleted, it couldn’t hold itself together and blew away to nothing but dust, the dust bowl of a hundred million acres that lost all or most of its topsoil.

The information is available. Studies demonstrate, experiments show, and experience teaches us how to care for the soil on which our lives depend. The facts are there, lessons from the past that can warn us about the future: we can project what effects different actions taken today will have on the soil. And yet all this knowledge is not enough, because understanding is missing. All the facts are not enough, because emotions and attitudes run counter to them. The way the actual soil is treated is a result of attitudes and philosophies that can differ even in the same geographical region. Interestingly, in the North China Famine of 1920–21, though a foot of topsoil was lost from hundreds of millions of acres of land, there were exceptions: around the Buddhist temples, the soil was deep, black, and rich in humus, because the Buddhist philosophy stipulated the protection of the forests.

You are what you eat is true in body but also in mind, for you become what you think. What you attend to, what you tend, tends to flourish: if you attend the feast of the soil, then you are feeding your mind with a green thought in a green shade; feed your thoughts with mental glyphosate, and your mind operates a toxic sterility.

The dominant culture (originating from Ancient Greek roots and now widely spread all over the world) privileges what is above rather than what is below: it looks up rather than down. Respect is accorded to Her Royal Highness; God in the highest; heavens above. We speak with contempt of the “lowest of the low”; dislike being in the “depths” of despair; and aim for the “heights” of success. Soil is treated with contempt because it is “beneath us.” We English speakers misuse the word “soil”: when we say something is “soiled,” we express not just disdain but visceral disgust, speaking with revulsion of the very thing that sustains us. While heaven is above, hell is “below.” The Fall was our downfall out of an unearthly paradise onto mere earth. Although Adam is named from the Hebrew “earth,” as if the wisdom inherent in language was compelled to acknowledge our identity with soil, Genesis itself revolts against earth; the lowest of creatures is the worm, creeping on the ground.

“It may be doubted whether there are many other animals which have played so important a part in the history of the world, as have these lowly creatures,” wrote Darwin. His courage took many forms: not only in his theory of evolution, but in his lifelong love of the lowly worm. “When we behold a wide, turf-covered expanse, we should remember that its smoothness, on which so much of its beauty depends, is mainly due to all the inequalities having been slowly leveled by worms,” he wrote.

Leveling inequalities conjures a social and political rhyme, suggesting the level earth as a level playing field, and the leveling of unequal lives. The spirit of leveling holds humility close to its heart; it has social grace and ancient wisdom. Worms, the original levelers, are creators of worlds. And we humans are destroyers of the only world we have.

The words humus, human, and humility are related. They are cognate words growing from the same Proto-Indo-European root dhghem. “Humus,” from Latin, means “earth” or “ground,” and “humble” means “lowly,” near to the ground. “Human” as a word reminds us that we are made of earth. If humility were imagined as a visible thing, it would be soil: quiet, brown, soft, maintaining networks underground and feeding the whole of the living world. We can learn about soil, yes, but better perhaps, we can learn from soil some of the humblest of lessons, of giving, respecting, and belonging. In my garden, my bare feet can feel the earth between the apple trees. Here anxiety leaves me and I feel safe. To have a garden is a privilege, but access to earth is something we all need in some way, shape, or form, for we, like trees, need our human roots in the humus of the soil beneath our feet.