Feature

Corn

Tastes Better

on the

Honor System

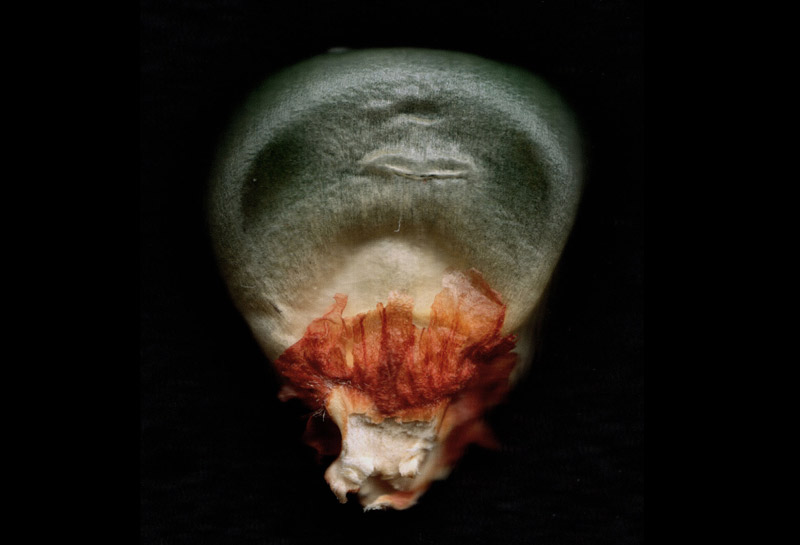

01. Oaxaca Green

I hold in my hand the fruit of genius, a miniaturized product that powers itself by unfurling self-generated solar cells. Its sophisticated internal codes enable it to replicate itself ten thousandfold without need of a 3-D printer. Under its glassy surface, an intricate network of membranes harness whizzing electrical circuits to sequester atmospheric carbon, purify water, and produce breathable oxygen. And if these features are not enough, it is the most sophisticated food production technology ever devised. With multiple apps already installed, it can make tamales, bourbon, soda, muffins, and diesel fuel. This marvel of science comes to us, free of charge, not from the high-tech engineers of Silicon Valley, but from the high-TEK developers living in the Balsas River Valley of central Mexico more than nine thousand years ago. It comes to us not from Apple, but from Maize.

I hold in my hand four seeds in the colors of the medicine wheel: thundercloud black, solar yellow, pearly moonlight, and blood red. I hold in my hand the memory of my ancestors in the garden. The DNA in every cell carries the story of brown fingers poking these seeds into the earth, fingers just like mine, with dirt under their nails. These farmers nurtured not only food but extraordinary genetic diversity, with the capacity to adapt to changing climates and an always uncertain future. I could use some of that now. This is the fruit of sophisticated indigenous science: traditional ecological knowledge, known as TEK. The DNA beneath the shiny seed coat is the source of resourcefulness, the creativity of corn married to the nurture of the human. I hold in my hand the multicolored fruit of collective genius, an agreement between sun, soil, water, plant, and farmer. They have entered into a covenant of reciprocity: if the maize will take care of the people, the people will care for the maize.

When we speak of “technology,” we’re often thinking of the consumer electronics and industrial processes that tint the cultural landscape of the Digital Age. But, a grinding stone, an irrigation system, and an ear of corn are also technology, a word that derives from the Greek tekhne, meaning an art or craft. Technology is simply the application of human knowledge to solve problems, fulfill needs, or satisfy wants. A factory synthesizing high-fructose corn syrup is technology born of science and engineering, and so is the process of domesticating, breeding, and processing corn by indigenous farmers. The heritage corn seeds in my hand and the corn products on your plate are manifestations of both high tech and high TEK.

The tools we choose to adopt influence how culture develops and also reflect a culture’s values. Corn is central to both indigenous and agro-industrial societies, but the way in which Zea mays is understood and used by each could not be more different.

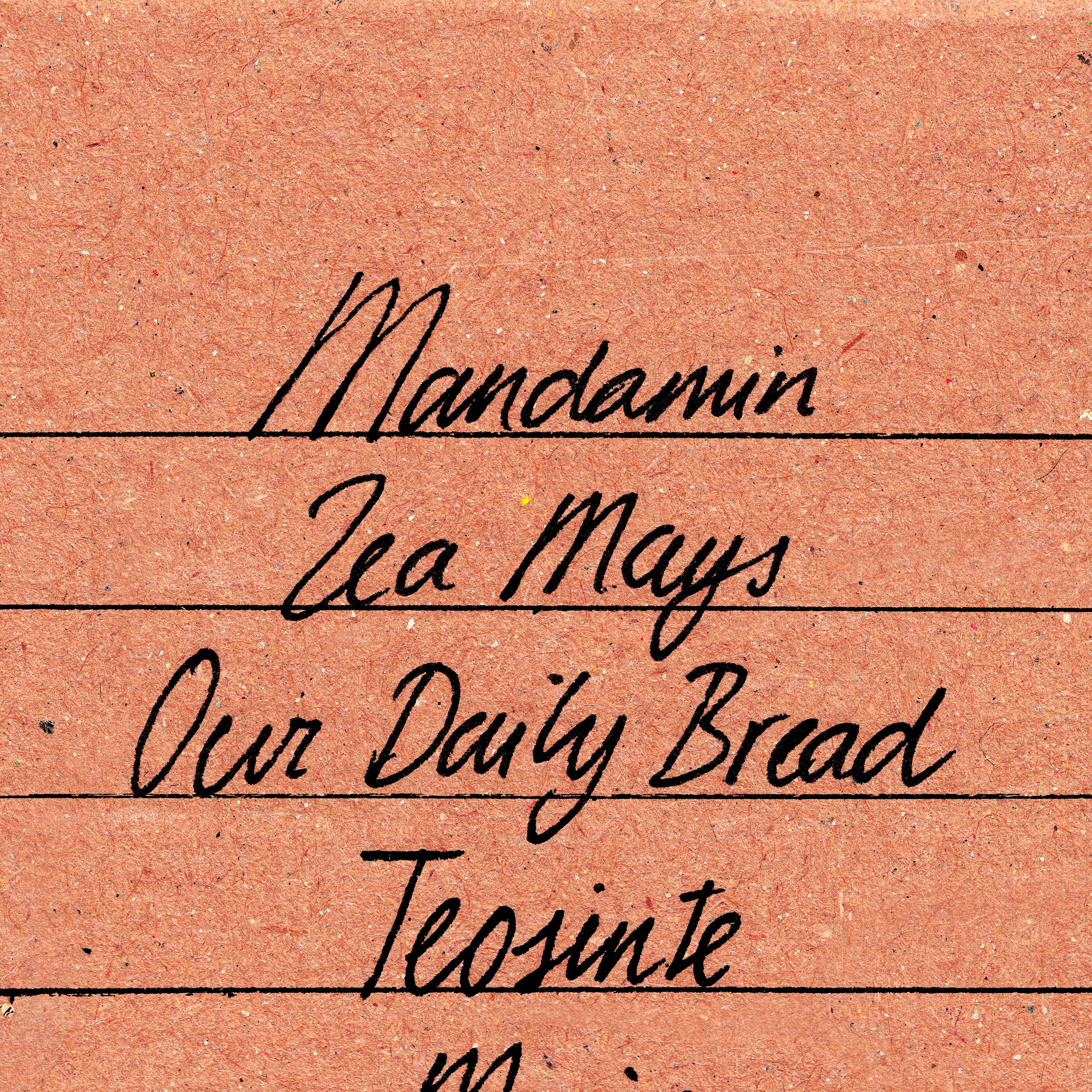

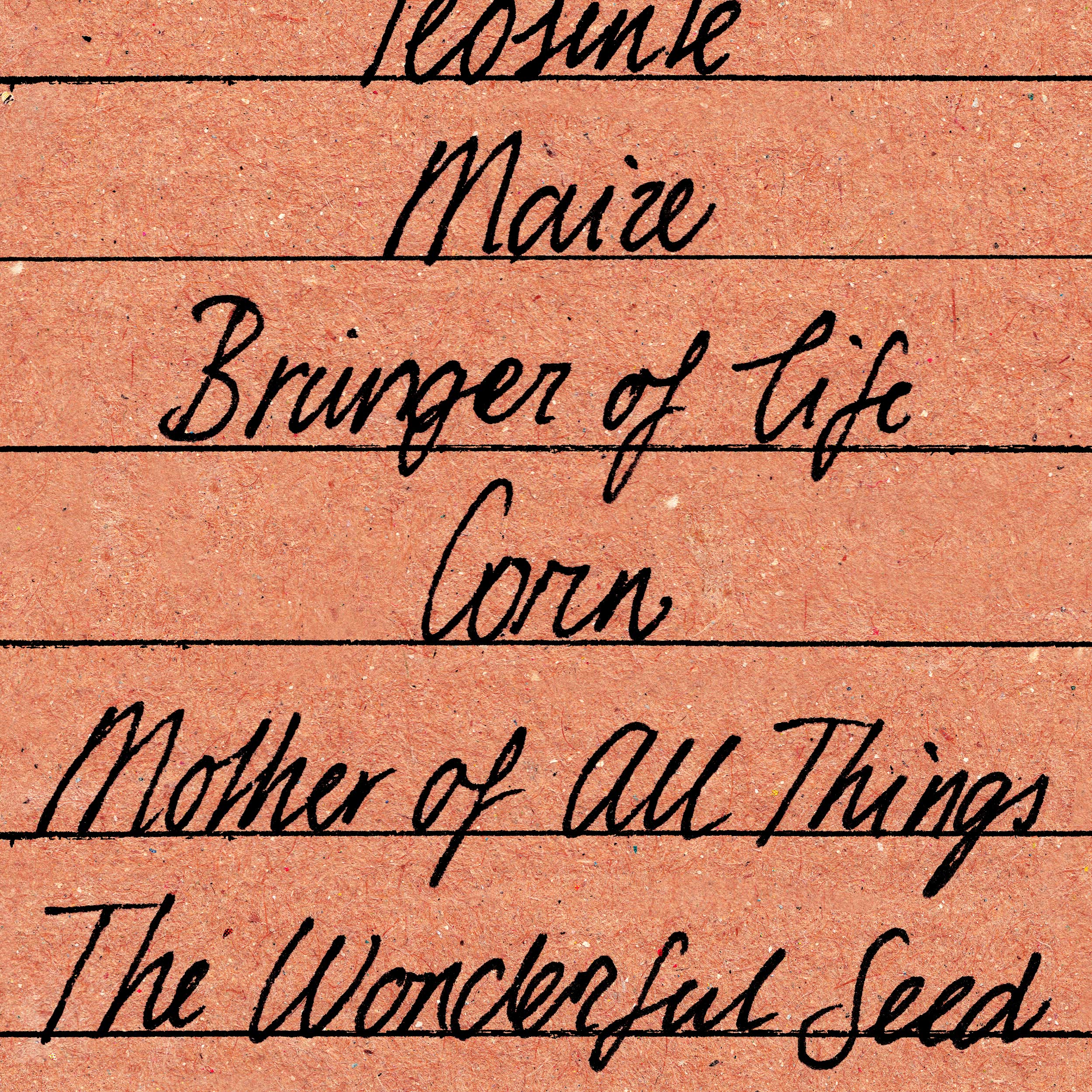

Maize or corn? This remarkable plant has been known by as many names as the peoples who have grown it: The Seed of Seeds, Our Daily Bread, Wife of the Sun, and Mother of All Things. In my own Potawatomi language, we say mandamin, or the Wonderful Seed. The scientific name is Zea mays, “mays” referring to the Taino name that Columbus recorded in his journal when first tasting “a sort of grain which they call mahiz, which very well tasted when boiled, roasted, or made into porridge.” Mahiz, meaning the “Bringer of Life,” became the word maize in English. These indigenous names honor maize as the center of culture and reflect a deeply respectful relationship between people and the one who sustains them.

The term used for the modern crop carries none of this feeling and is rooted in intentional blindness to the original meaning of the plant. Rather than adopt the reverent indigenous name, English settlers simply called it corn, a term applied to any grain—from barleycorn to wheat. And so it began, the colonization of corn.

I live in the lush green farm country of upstate New York, in a town that likely has more cows than people. Most everyone I know grows something: apples, hops, grapes, potatoes, berries, and lots of corn.

As I carry my seeds to the garden, I can hear the growl of my neighbor’s tractor and catch a whiff of the ammonia fertilizer that he is spraying on the fields. I saw his tractor headlights going back and forth late last night, getting ready. It’s an intense time of year, so much rests on preparation and timing. He’s oiled every gear and loaded the seed. We both know the rain is coming; it’s planting time. I’m getting ready too, preparing the ground with a whiff of a smudge, asking permission of Mother Earth to receive these seeds, and celebrating the life inside each kernel with a song.

My handful of Red Lake flint corn seeds were a gift from heritage seed savers, my friends at the Onondaga Nation farm, a few hills away. This variety is so old that it accompanied our Potawatomi people on the great migration from the East Coast to the Great Lakes. If you could carry only a single pouch of seeds, this would be the one to choose, with nutrition for physical health and teachings for spiritual health. Holding the seeds in the palm of my hand, I feel the memory of trust in the seed to care for the people, if we care for the seed. These kernels are a tangible link to history and identity and cultural continuity in the face of all the forces that sought to erase them. I sing to them before putting them into the soil and offer a prayer. The women who gave me these seeds make it a practice that every single seed in their care is touched by human hands. In harvesting, shelling, sorting, each one feels the tender regard of its partner, the human.

My neighbor bought his seeds from the distributor. They are a new GMO variety that he can’t save and replant but must buy every year. Unlike my seeds of many colors, his are uniform gold. They will be sown with the scent of diesel and the song of grinding gears. I suspect that those seeds have never been touched by a human, but only handled by machines. Nonetheless, when the seeds are in the ground and the gentle spring rain starts to fall, I suspect he looks up at the sky and prays. We both stand back and watch the miracle unfold.

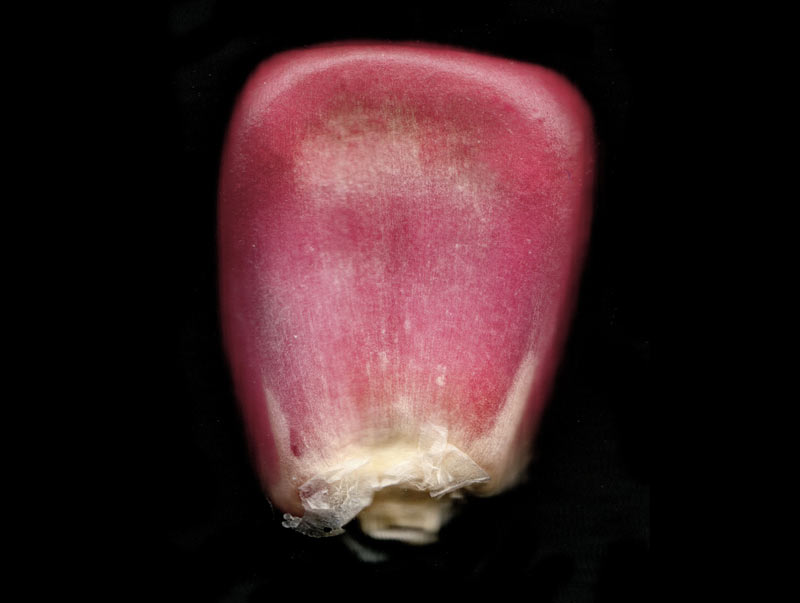

02. Mexican Pink

Our different ways of planting reflect not only the different scales and goals of our work, but also our fundamental relationships with the plant. In the western worldview, the plant is understood as a photosynthetic machine of sorts, without perception, will, or personhood. The seeds my neighbor drills into the ground are thought of as objects, hardly different than the fertilizer or herbicide, another cog in the farm-become-factory. In this worldview, plants are placed low on a hierarchy of life—a perception which is flipped upside down in indigenous ways of knowing. Over the hill at the heritage farm, plants are respected as bearers of gifts, as persons, indeed oftentimes as teachers. Who else has the capacity to transform light, air, and water into food and medicine—and then share it? Who cares for the people as generously as plants? Creative, wise, and powerful, plants are imbued with spirit in a way that the western worldview reserves only for humans.

Science and technology go hand in hand, each spurring the other forward. Western science is a powerful way of generating knowledge, but it is not the only one. Long before colonists came to our shores, there were scientists here of every kind, including botanists, agronomists, and geneticists, practicing indigenous science and developing regenerative technologies. The nature of these two ways of understanding the world is written in vivid green ink in our respective cornfields.

Western science makes the claim to pure objectivity and intentionally banishes subjectivity from its explanations in favor of reductionist, strictly materialist approaches. I’m trained as a scientist, and I honor the importance of this method. There’s good reason for it when the questions to be answered are “true or false.” But there are other, bigger questions, for which exclusion of human values may lead to unintended outcomes.

The four colors on my Red Lake flint cob are said to represent the four colors of the medicine wheel, which is a symbol of the holistic indigenous approach to knowledge making. Among their many meanings, the four colors remind us that we humans have four ways of perceiving and understanding the world, with mind, body, emotion, and spirit. There is no strict separation between subjective and objective but rather encouragement to consider what we might learn from using each of these powerful abilities. The combination provides insight into not only questions of “true or false” but also questions of “right and wrong.”

Maize is so central to life that it holds a powerful place in the creation stories of the Maya. After making the beautiful Earth, the creator gods set about making beings worthy of these gifts. After several failed attempts, the twin creators took two different colors of corn and formed them into humans. People made of maize were most pleasing to the gods for their gratitude for life, their care for other beings, and their joy. Maize, the Mother of All Things, gave life to the People. The books that recorded these stories were burned by the colonists, who saw themselves as made in the image of God, not from a lowly plant.

Biochemists confirm that we are indeed people made of corn. Because of its unusual photosynthesis, corn leaves a signature in our tissues written in its particular ratio of carbon isotopes. Corn-eating peoples of the Americas carry a very different ratio of these isotopes in their flesh than the wheat eaters of Europe or the rice eaters of Asia. One biochemist concluded that Americans are basically “walking Fritos.” If you walk through the grocery store reading labels, you’ll find that nearly 70 percent of processed foods contain corn in some form: corn syrup, corn oil, corn starch, and more. Eggs, dairy, and meat find their way to our plates and into our cells through feed corn. Corn is the keystone of our food chain. How ironic that the conquistadors were at first fearful of eating this delicious grain, thinking that if they ate the food of “savages,” they would become like them. Unfortunately, that fear proved to be ungrounded.

CORN IS USED FOR THE PRODUCTION OF...

toothpaste, makeup, and shampoo.

CORN IS USED FOR THE PRODUCTION OF...

soda, candy, and salad dressing.

CORN IS USED FOR THE PRODUCTION OF...

oil, gas, and ethanol.

Despite millions of acres of waving green leaves and golden ears to remind us, processed corn is so ubiquitous in our lives that it makes us think of corn as a product and not as a plant being. What is our relationship to the plant that has quite literally made us?

The writings of some early colonists reveal that they thought corn a primitive crop, because it did not require machines or draft animals to cultivate and process, as did their familiar wheat. They mistook the apparent ease with which corn fed the people for a lack of agricultural sophistication, rather than recognizing the genius of the system. Corn did not happen by happy accident; Charles Mann has called its evolution a “bold act of conscious biological manipulation” by Mayan farmers.

Unlike other cultivated plants, corn has been called a “human invention that does not exist naturally in the wild and can only survive if planted and protected by humans.”1 The process of domestication dramatically changed the plant to the maize we know today. Artificial selection by observant and knowledgeable farmers led to a plant whose form and function allowed it to become one of the most efficient food producing technologies ever invented. By 6500 BC, corn was cultivated more widely across the Americas—with higher yields and multiple uses—than any other plant.

How did this come to be? It’s a story of the dance between the plant’s unique gifts and the human gift for technology: not technology in the sense of autonomous machines that separate us from the living world, but a sacred technology, which unites us. Using indigenous science, the human and the plant are linked as co-creators; humans are midwives to this creation, not masters. The plant innovates and the people nurture and direct that creativity. They are joined in a covenant of reciprocity, of mutual flourishing.

One corn origin story of our Potawatomi people names corn as the first mother of the people, a woman who trailed a green leaf behind her. Out of love for the hungry children to come, she gave up her own life, and when laid in the fertile ground, she became Mother Corn, sacrificing her own beautiful seed children to all the generations that follow.

Maize agriculture is simultaneously pragmatic and sacred. In dominant society, we would not consider cornbread a sacred food; it is simply a product, a foodstuff, so removed are we from its origins. In purely objective western scientific thinking, corn is simply a package of starch, protein, and lipids conveniently held together in a seed. But, when corn is called “Wife of the Sun” or “Mother of All Things,” we remember that the kernels are not just “stuff” but a gift from the plant, a being created of light and air and water, the inorganic brought to life in a union of sky and earth that we ourselves might have life. This is medicine wheel thinking that allows spirit and matter to converse.

Reverence for maize has been lost in industrial agriculture but vibrates in the air at the heritage seed farm at the Onondaga Nation, where braids of multicolored ears hang from the rafters. Onondaga Nation is the center of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy, whose skilled farmers once tended cornfields that stretched for miles. “These seeds are our ancestors,” says farmer Angie Ferguson. “Each seed carries the knowledge of the gift it was given. It knows what to do. It’s a miracle to put a seed in the ground and watch what happens.” Angie is a leader in the Braiding the Sacred movement, which stewards the seeds and is revitalizing indigenous agriculture, farmer by farmer, seed by seed, and song by song.

They call the process of bringing back the seeds and the respect for them rematriation. Seedkeeper Rowen White writes that “the word ‘rematriation’ reflects the restoration of the feminine seeds back into the communities of origin. The Indigenous concept of Rematriation refers to reclaiming of ancestral remains, spirituality, culture, knowledge and resources, instead of the more Patriarchally associated Repatriation. It simply means back to Mother Earth, a return to our origins, to life and co-creation, rather than Patriarchal destruction and colonization, a reclamation of germination, of the life giving force of the Divine Female.” They are replanting the sacred. Here, they remember the Corn Mother’s name.

Angie was given the responsibility of caring for a seed collection that represents a legacy of sacred technology. In gleaming rows of jars are hundreds of ears unlike any you have ever seen: four-inch ears of popcorn with seeds like jade, fourteen-inch ears, nearly black; magenta, ochre, speckled pink, blue, white, red, and calico; ears like wampum purple and white, colors of sunset, kernels marked by eagle wings; 6-row, 8-row, 20-row, straight, spiraled; corn for flour, corn for mush, corn for roasting, corn for soup, for chicha, for medicine used in ceremony; deep-rooted corn for the desert, short season corn for the north. If corn and farmer could think of it, it is in those jars.

The intent of indigenous corn breeding was to promote genetic diversity, for in diversity lies stability and food security. Farmers worked with the plant, skillfully guiding it to meet the nature of the landscape and the needs of the people.

The precise details of how maize was domesticated from its wild ancestor remain a bit of a mystery. Archeological and genetic analysis reveals that corn was likely first domesticated about 9,000 years ago from the ancestral wild grass teosinte, Zea mays ssp. parviglumis. “Teosinte” is an indigenous Nahautl word meaning “sacred ear of corn.”

9,000

Years ago

Indigenous peoples of Mexico begin selective breeding of teosinte in the Balsas River Valley of central Mexico.

Teosinte, a Nahautl word meaning “sacred ear of corn,” is the wild ancestor of maize.

5,000

Years ago

Domestication and hybridization of maize develops throughout South America.

When corn is called “Wife of the Sun” or “Mother of All Things,” we remember that the kernels are not just “stuff” but a gift from the plant.

4,000

Years ago

The oldest evidence of maize cultivation was found in the American Southwest.

The variety known as Chapalote develops longer cobs and more rows per ear.

1492

Europeans arrive in the Americas and bring maize back to Europe.

Mahiz, meaning the “Bringer of Life,” became the word maize in English.

Today

Corn—a generic European word denoting any grain—is grown worldwide. It is widely hybridized and injected with GMO traits. Corn grown in the United States primarily feeds cars and livestock.

Mandamin is a Potawatomi word meaning “The Wonderful Seed.” The word is still in use today.

Swipe

↔

Teosinte can interbreed with maize and is welcomed at the edges of traditional farmers’ fields, where it is greatly valued for its ability to “strengthen” the vigor of the corn crop. Genetic research shows that crossing between ancestral teosinte and the evolving corn seems to have played an important role in the changes that accompanied domestication. This process of backcrossing a hybrid with an ancestor, known as introgression, is an engine of genetic diversity, creating new genetic combinations that the farmer can then select from her field and propagate. Introgression is still used in contemporary corn breeding, but the innovations that agribusiness claims with patents, in fact, originated in indigenous science, which grew from intimate knowledge of the nature of maize and its ecological needs.

But let’s be honest—we can’t fully credit humans for inventing corn. Maize is such an innovative departure from her grassy kinfolk that, if an original patent was to be granted for brilliant design, it should be awarded to the plant herself. Humans noticed what maize invented and then adapted it to support their own lives.

A hallmark of many technologies is that they harness energy other than our own to accomplish a task. Maize, the Life Bringer, is a master of energy transformation, accomplishing a feat that engineers have yet to duplicate: photosynthesis.

03. Chapalote

Part of the story of maize’s exceptional productivity lies in its supercharged C4 photosynthesis—present in only 5 percent of flowering plant species. The C4 process enables high efficiency in converting atmospheric carbon dioxide to the sugary building blocks of plant life. Corn can be as much as 50 percent more productive than typical C3 plants, like wheat or potatoes. If you look closely, you can see where the magic happens. Each of the long veins in a waving corn leaf is surrounded by a circle of chubby green cells. They seem a different shade of green than the leaf cells—and they are, which is due to a different kind of chloroplast, the cellular engine responsible for turning carbon dioxide into food. These special bundle sheath cells have unique carbon-capturing enzymes, which are very good at what they do. If you imagine yourself inside the leaf, you could watch carbon dioxide molecules shuttle across the glistening membranes in the clutches of a specially designed enzyme. Unlike the C3 apparatus, which can get hijacked by errant oxygen, every single CO2 molecule they grab gets turned into the precursor of your cornbread—sugar which is then polymerized to starch for easy storage in the seed.

Maize shares the fibrous roots, wind-pollinated flowers, and long leaves of the grass family, but in many ways it is an outlier, not least by its extraordinary size, earning it the description of “a monstrous grass.” It lives at human scale, defying the inconspicuous nature of its relatives in ways that reveal its long domestic partnership with people. Corn is the only food plant I know that shares the size of the human body—trees are far larger, most crops are smaller, but corn and people can stand face-to-face. Many grasses, like the ones in your lawn or a tallgrass prairie, spread and make many identical shoots from a single seed, which is known as tillering. However, corn does not tend to tiller; instead, it focuses all of its energy to make a single, genetically unique stalk as tall and sturdy as a farmer.

The distinctive way that corn flowers made it ideal for breeders. The male and female flowers are on different parts of the plant, making it possible to influence the parentage of the seeds. The male tassels shed pollen from the top of the plant, and the female flowers, sheathed inside the ear, are connected to the outside world only by the corn silk, the long tubes that are the conduit for fertilization. Each strand of corn silk leads to a waiting ovary, which if pollinated, becomes an individual kernel. The astute farmer can cross males of one type with females of another to get new varieties. With whole cobs of different offspring to choose from, the farmer selects the best genetic combinations every year, gradually improving and changing the plant through artificial selection. Whether open-pollinated or the result of careful matchmaking, maize is a plant of extraordinary genetic diversity. Modern corn of industrial agriculture grows a uniform, homogeneous product, so unlike the riotous variety of indigenous maize.

An ear of corn represents an entire family of seeds anchored to the cob. No other plant packages its energy-rich seeds so efficiently. This is good for the plant and good for the people. Singly borne seeds are each vulnerable to pests, disease, and hungry birds, but corn protects them all together in sheathing layers of husk. It’s much easier to harvest seed-packed ears than individual seeds. This efficiency means a single plant will generously fill the soup pot for its caretakers. With all those offspring wrapped in a husk blanket, maize embodies her name, the Corn Mother.

These same traits that make maize so valued by humans also make it impossible for her to survive without us. With all those kernels packed tightly together and completely enclosed by the husk, the seeds are trapped. They can’t disseminate themselves. They need human hands to liberate them from the husk, to twist them from the cob and to sow them in fertile soil. They need us to poke them into the earth every spring. People and corn are linked in a circle of reciprocity; we cannot live without them and they cannot live without us.

As spring progresses my neighbor’s sprouting corn inscribes glowing green lines against the dark soil, drawing the contours of the land, like isoclines on a living topographic map. Its hypnotic evenness makes it look like it was planted by machine, which of course it was. I smile at the occasional deviation where the lines go askew for a few yards. Maybe the driver was distracted by an incoming text or swerved to avoid a groundhog. His distraction will be written on the land all summer, a welcome element of humanity in a food-factory landscape.

My garden looks different. The word “symmetry” has no use here, where mounds of earth are shoveled up in patches. I’m planting the way I was taught, using a brilliant innovation generated by indigenous science: the Three Sisters polyculture. I plant each mound with three species, corn, beans, and squash—not willy-nilly, but just the right varieties at just the right time. This marvel of agricultural engineering yields more nutrition and more food from the same area as monocropping with less labor, which my tired shoulders appreciate. Unlike my neighbor’s monoculture, Three Sisters planting takes advantage of their complementary natures, so they don’t compete but instead cooperate. The corn provides a leafy ladder for the bean to climb, gaining access to more light and pollinators. In return, the bean fixes nitrogen, which feeds the demanding corn. The squash with its big leaves shades the soil, keeping it cool and moist while also suppressing weeds. This is a system that produces superior yield and nutrition and requires no herbicides, no added fertilizers, and no pesticides—and yet it is called primitive technology. I’ll take it.

Across the valley, the uniform corn rows in their high-tech isolation look lonely to me. But they are visited regularly by tractors spraying chemicals.

The United States is the world’s largest producer of corn, with over ninety million acres of land planted to this crop. The majority is grown in the Corn Belt.

Corn requires more irrigation water than any other crop in the United States.

Corn accounts for nearly 40 percent of total pesticide use in the United States.

01

02

03

My neighbor is growing feed corn for livestock, which is harvested when dry and hard. Thankfully, a few of my other neighbors have fields of sweet corn for fresh eating. Sweet corn is a sugary mutant that arose from the huge storehouse of genetic diversity held by Zea mays. I like to get mine from the farm stand where it is picked each afternoon; so when you stop by on the way home from work, it is only hours off the plant. There’s a coffee can next to the heap of still moist ears where you leave the money. Corn tastes best on the honor system.

04. Red Sweet Corn

The modern maize that we enjoy as fresh-picked sweet corn, dripping with butter on a summer evening, has not always had this abundant form. In fact, we might not recognize its ancestor at all.

The story of corn domestication can be read in archeological strata, from pollen cores, from old fireplaces and cooking pots, and from middens abandoned millennia ago. Corn kernels and cobs are well preserved, and layer by layer of painstaking excavation at archeological sites—like Bat Cave, New Mexico—record the long and changing relationship between maize and the indigenous peoples who cultivated it.

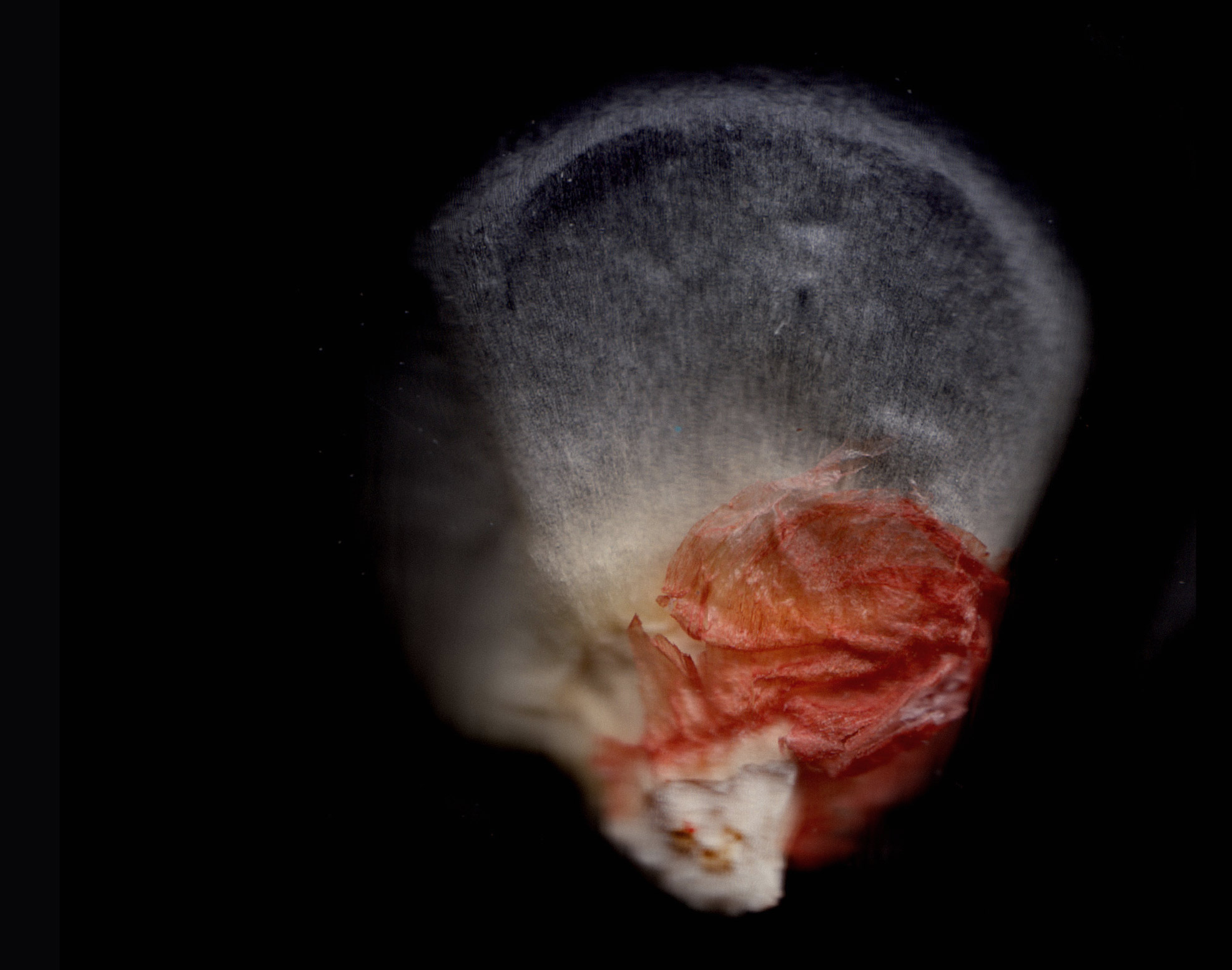

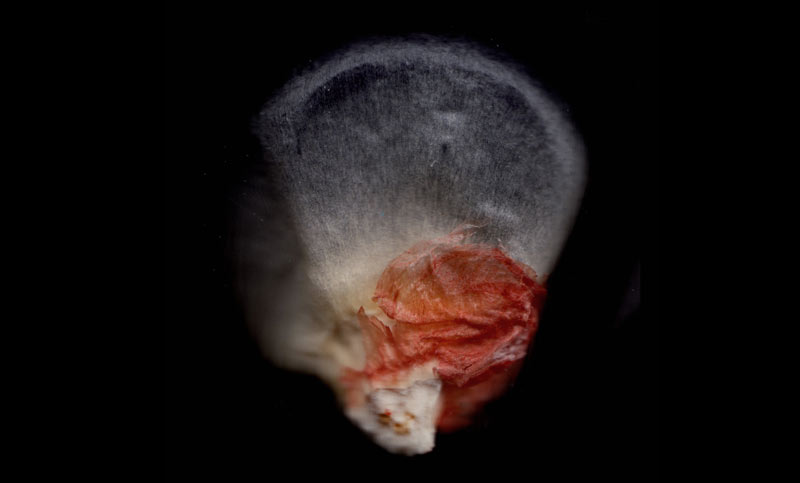

The earliest cobs that have been unearthed are only an inch long and hold just two short rows of kernels. These very early corn seeds were only a tenth the size of modern kernels and hard as stone, which made them nearly inedible. So why did people grow them? Ancient farmers found a way to use this otherwise unavailable resource by developing a technology that made these jaw-breaking seeds edible. The earliest known method of processing corn was to heat the seeds in a dry ceramic vessel over a hot fire. This caused the moisture inside the seed to rapidly expand and explode through the seed coat in a puff of white. Popcorn! Our modern snack is an ancient technology for converting an inedible seed to a staple food. Garlands of popcorn were used in ancient ceremony to celebrate this tasty gift.

Archeological strata also include the early stage variety of maize, known as pod corn; today referred to as “grandfather corn” for its great antiquity. Each individual seed was held in its own short husk, like a papery wrapper. Centuries of artificial selection and skillful breeding led to a corn cob that has up to twenty rows of large seeds, collectively wrapped in one husk. Under cultivation, the plant went from having a short stature, with many long branches and numerous small cobs, to the stately architecture of modern corn, with larger ears and softer seeds.

The corn I am planting and that Angie grows carries the genes of many corn lineages that were stewarded by their partners, the farmers. The diversity arises from the intrinsic genetic makeup of the plant. It needs to be said, that all of the genes—wildly recombined with encouragement from the farmer—are corn genes. The identity and genetic sovereignty of Mother Corn is intact.

The corn my neighbor is planting, like nearly all of the corn planted in the United States, is genetically modified. Genetic engineering has been used to forcibly insert foreign genes from other organisms into the DNA of maize. The genes of bacteria are introduced to make the corn more resistant to disease and insect attack, both of which plague crop monocultures. Monsanto Corporation, in concert with manufacturers of herbicides, have inserted foreign genes that allow the corn to survive being sprayed with Roundup, while the weeds are killed. This technology most certainly increases production efficiency but also poses a threat to beneficial insects, to soil, and to traditional farmers whose crops have been contaminated by pollen flow from GMO corn. This is a technology that uproots the original agreement between maize and people and makes corn subservient to the needs of agribusiness. The genetic integrity of The Wife of the Sun has been compromised. There’s a word for forcible injection of unwanted genes.

05. Floriani Red Flint

Innovation tends to spark more innovation, and ancient farmers were part of this cycle, finding new uses for corn in making materials, such as cordage from leaves, medicine from the silks, and delectable ways of cooking the seeds, from dumplings to tamales. Among the most important inventions was nixtamalization, a kind of applied biochemistry that dramatically improved the nutritional content of the grain. Corn is an excellent energy source, but a diet based entirely on maize can lead to pellagra, a nutritional disease caused by low niacin. However, if the maize is processed in a strongly alkaline solution, the niacin present can then be readily absorbed by the body. So, traditional people have cooked maize with whatever calcium hydroxide sources are at hand—from ground seashells to lye. That technology continues today.

When I make our traditional Potawatomi corn soup, I begin by boiling the stony seeds in a pot of hardwood ash. They do the same at Onondaga and wherever corn soup is made. The kernels emerge from the gray slurry with the hulls loosened and the niacin in place. Nixtamalization has a host of other benefits. Lye-treated corn can be formed into a dough as the polysaccharide bonds are loosened, while untreated corn is too friable. Nixtamalization also removes any traces of aflatoxins, a serious toxin produced by the mold fungi that may inhabit stored corn. This is a bioprocessing technology that increases nutrition, uses all-natural materials that are close at hand, and produces no waste with minimal energy expended—the sophisticated application of indigenous science.

As contemporary bioengineers learn more about corn’s chemical constituents, they too are developing promising new materials from corn, such as bioplastics, textiles, adhesives, and biofuels. This new demand produces competition between hungry people in some regions of the world and hungry cars in need of cheap gas in others, and you can predict who is winning. Western science and its worldview allow us to answer the question “Can we do it?” but are ill-equipped to address the question of “Should we?”

When harvest time rolls around, my neighbor and I are grateful for the warm, windy days that make dry corn rattle in the breeze. At this end of the season, we watch for rain again in order to bring in the crop before it gets wet.

It takes a fleet of vehicles for my neighbor farmer to bring in the harvest. Hopper trucks sidle up to a ceaselessly moving combine, which shoots a golden stream of grain from a chute into the truck. An empty one takes the place of the full ones heading to the barn. My road is crunchy with spilled kernels, and the squirrels are delighted—and plump.

On the heritage farm at Onondaga, the community gathers the ears in big baskets. In the barn, everyone gathers to pull back the husks and braid them together so they can be hung from the rafters for drying. Usually there is much laughter and chatter, but some days the barn is quiet while everyone is at ceremonies, giving thanks for the harvest. Once the corn is dry, the shelling starts. Kids at the school love this part: twisting the kernels from the cobs into cardboard boxes. Other hands will sort the abundance into three bins under Angie’s guidance. The perfect seeds go into a bin for next year’s planting, preserving the age-old process of artificial selection, of planting the best and eating the rest. Kernels of unusual color or size are set aside for consideration of their potentials. The next best seeds, the ordinary ones, go into the food bin. The promised reciprocity is underway; the agreement is alive—the people cared for the corn and now the corn will care for the people. The people here remember what the Corn Mother taught them.

There are always a few misfits, the shrunken or broken or immature. These are not thrown away but kept in the third bin. Angie and the farm crew scatter them outside, sharing with wild relatives in the hungry time of winter. The squirrels are fat here, too.

Most all of the Onondaga corn harvest is shared by the community, as corn soup, corn bread, and cornmeal mush with maple syrup and berries. Angie and the crew are traditional chefs as well, restoring food culture and its nutritional benefits. All the summer’s work of people and plant fills the bellies of friends and family and takes its rightful place at traditional ceremonies, nourishing people and culture at the same time. This harmonious image is far from the norm.

90%

… of corn grown in the United States is grown from GMO seeds.

40%

… is consumed by livestock.

40%

… is used for the production of ethanol.

10%

… or less is consumed by humans.

Most corn is eaten by no one. Less than 10 percent of the US corn crop ever finds its way to your table, and much of that is in the form of high fructose corn syrup in soda and processed foods. The middle of our country is a cornfield roughly 1500 miles long. What happens to all that corn if it’s not feeding people? About half of it fattens cattle, pigs, and chickens and fuels dairy production. In a hungry world, we have to remember that the efficiency of converting corn calories to animal calories is low. For every 100 calories a person could receive from eating corn, only 15 of those calories will make it to your plate in the form of animal protein. Since 2011, however, more corn has been used for ethanol production than for consumption by humans and livestock combined. At what cost?

06. Rio Grande Blue

Corn production today uses more natural resources than any other crop. Around 90 million acres are planted in corn, and the last remaining remnants of native prairie and grassland are being plowed under for corn every year. Corn is a hungry crop and a thirsty one. Vast amounts of water are consumed, and a staggering amount of fertilizer. Corn not only consumes a great deal—it produces a huge amount of waste. Much of that fertilizer never even makes it into the plant, instead it is washed downstream, producing toxic algal blooms in waters everywhere along the way and ultimately creating the growing dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico. Dead rivers, lost biodiversity, say farewell to prairies and bobolinks and meadowlarks, to say nothing of precious topsoil leaving the fields and silting the rivers. The economic pressure behind this ongoing expansion of cornfields has little to do with filling empty bellies. In today’s agribusiness, we feed more cars than people.

I don’t blame my farmer neighbor for industrial agriculture. He’s been harnessed to a system that treats him like a cog, too. His family has farmed this valley well for generations and had to adapt to changing pressures in order to stay on the land. The honorable calling of farming is being dishonored by a worldview and economic institutions that relentlessly demand taking more without regard for giving back. He’s been colonized, too.

Watching train cars of golden yellow kernels unload into ethanol factories creates a gnawing pain in my gut; it’s the pain of betrayal. The Mother of All Things, the Wonderful Seed, did not agree to this. It’s a long, long way from seeing her as a sacred being to an industrial commodity. How did we get here?

Colonization is the process by which an invading people seeks to replace the original lifeways with their own, erasing the evidence of prior claims to place. Its tools are many: military and political power, assimilative education, economic pressure, ecological transformation, religion—and language.

Colonists take what they want and attempt to erase the rest. Conceiving of plants and land as objects, not subjects—as things instead of beings—provides the moral distance that enables exploitation. Valuing the productive potential of the physical body but denying the personhood of the being, reducing a person to a thing for sale—this too is a manifestation of colonialism.

There is another word tugging at my sleeve, asking for recognition. That word is slavery. Standing alone in straight lines in poisoned fields, forced to carry genes not their own, today sacred maize is enslaved to an industrial purpose: feeding cars and factories.

Corn? Maize? Mother of All Things? Renaming is a powerful form of colonialism in which the settler erases original meanings and replaces it with meanings of their own. This practice of linguistic imperialism also diminished corn from its status as Mahiz, the sacred life giver, to an anonymous commodity. Indigenous languages, lifeways, and relations with the land have all been subject to the violence of colonialism. Maize herself has been a victim, and so have you, when a worldview which cultivated honorable relations with the living earth has been overwritten with an ethic of exploitation, when our plant and animal relatives no longer look at us with honor, but turn their faces away. But there is a kernel of resurgence, if we are willing to learn.

The invitation to decolonize, rematriate, and renew the honorable harvest extends beyond indigenous nations to everyone who eats. Mother Corn claims us all as corn-children under the husk; her teachings of reciprocity are for all.

I’m not saying that everyone should go back to Three Sisters agriculture or sing to their seeds; although I admit that is a world I want to live in. But we do need to restore honor to the way that food is grown. Agribusiness is quick to point out that we cannot feed a world of nearly eight billion people with gardens alone. This is true but omits the reality that most of the corn we grow is not going to hungry people: it is feeding cars. There is another kind of hunger in our affluent society, a hunger for justice and meaning and community, a hunger to remember what industrial agriculture has asked us to forget, but the seed remembers. Good farming should feed that hunger, too.

I’m thinking of the way that grandfather Teosinte mingles with corn at the edge of a traditional cornfield, welcomed as a source of guidance and diversity. Might we invite ancestral knowledge into our fields for these same virtues? Unsustainable industrial agriculture needs philosophical gene flow from indigenous knowledge, a cross-pollination of respectful relationship to breed a new agriculture that honors the plants as well as the people. Together we can remember our covenant with corn, that she will care for the people, if we will care for her.

Corn tastes better on the honor system.

-

Gail Woody, “Where Corn Is King,” West Virginia Living, May–June 2013, 18–19.