Deep Time Diligence

Emmanuel Vaughan-Lee is an author, Emmy- and Peabody Award–nominated filmmaker, and a Sufi teacher. He has directed more than twenty documentary films, including Taste of the Land, The Last Ice Age, Aloha Āina, The Nightingale’s Song, Earthrise, Sanctuaries of Silence, and Elemental, among others. His films have been screened at New York Film Festival, Tribeca Film Festival, SXSW, and Hot Docs, exhibited at the Smithsonian Museum and London’s Barbican, and featured on PBS POV, National Geographic, The New Yorker, and The New York Times Op-Docs. His new book, Remembering Earth: A Spiritual Ecology, is forthcoming from Shambhala in summer 2026. He is the founder, podcast host, and executive editor of Emergence Magazine.

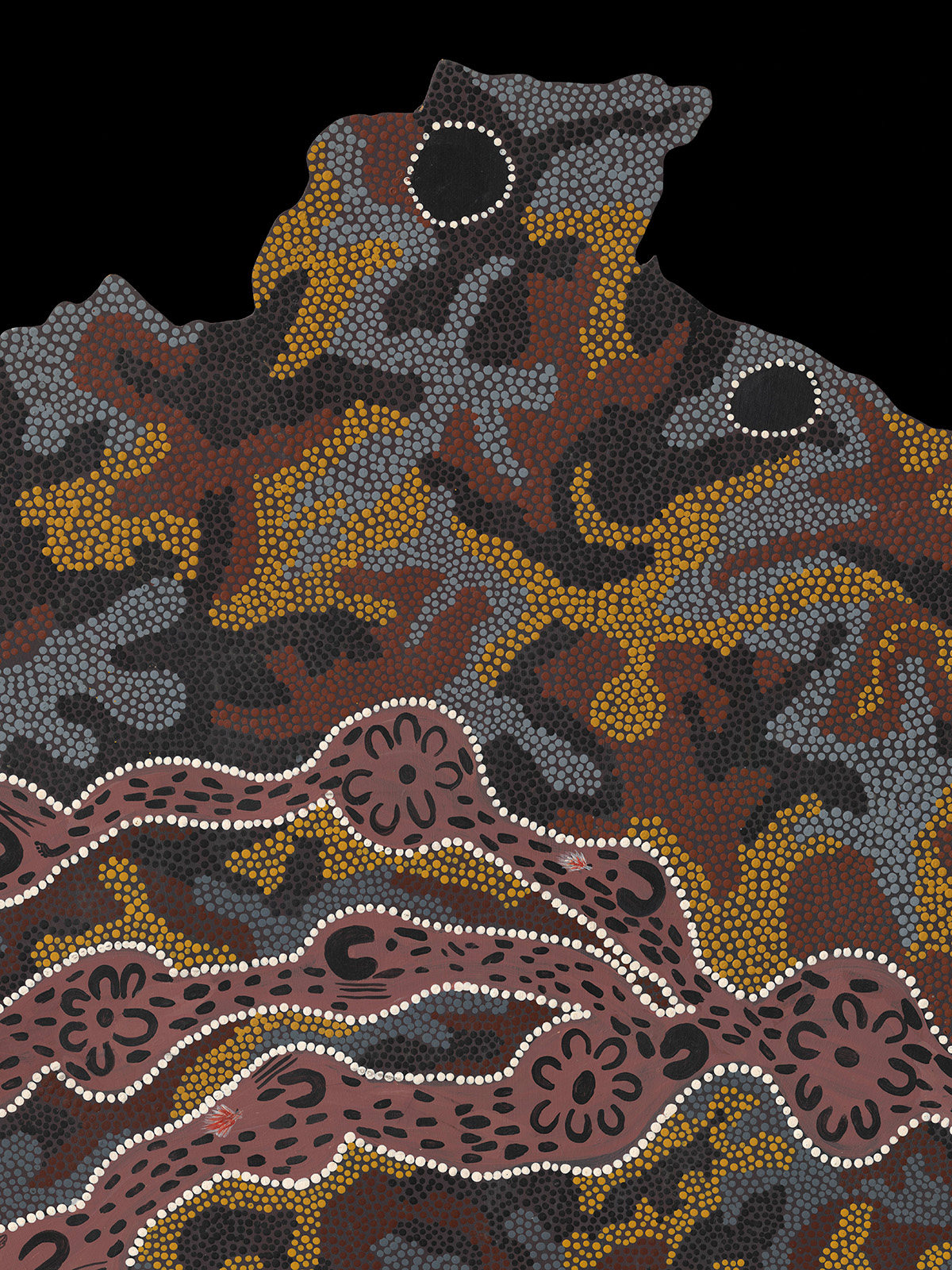

Tyson Yunkaporta is an Aboriginal scholar who belongs to the Apalech Clan in far north Queensland. He is the founder of the Indigenous Knowledge Systems Lab at Deakin University in Melbourne, the author of Sand Talk: How Indigenous Thinking Can Save the World and Right Story, Wrong Story: Adventures in Indigenous Thinking, and a carver of traditional tools and weapons. His work focuses on applying Indigenous methods of inquiry to address complex issues and global crises.

Aboriginal scholar and author Tyson Yunkaporta illustrates how deep time thinking, born of an intimate relationship between a place and its community, can radically reshape our relationship to the cosmic order.

Transcript

Emmanuel Vaughan-Lee Tyson, welcome. It’s nice to be in conversation with you today.

Tyson Yunkaporta Hey, how’re you going?

EVAs I think you know, time is a theme we’re exploring at Emergence this coming year. And this seems to be a subject that comes up often in your work, both in your previous book, Sand Talk, and your new book, Right Story, Wrong Story. And I remember when I read Sand Talk being struck by how you described the “futility” of trying to explain Aboriginal notions of time in English, where it is often described as nonlinear, which is not only a simplification of the Aboriginal notion of time, but only describes the concept by “what it’s not, rather than what it is”; and that there isn’t even a word for “nonlinear” in Aboriginal languages.

TYYeah, it’s strange, huh? Yeah, we don’t have words for those things. So it’s weird with languages where if you don’t have words for things then you know in that culture, in the root culture, there’s no utility for these things. But, also cultures are always evolving, so we pick these things up, but it takes a while, you know. So there’s no abstract nouns at all in Wik Mungkan, which is the language I speak, so it’s really tricky. But the thing about time is that there’s not a discrete word for just “time,” you know? Time is always the same as place.

EVRight, you talk about that in Right Story, Wrong Story.

TYYeah. If you are asking like, you know, what time something’s gonna happen, you use the word for place and you say, “What place?” So, it’s not confusing when you’re speaking the language, but it’s confusing when you try to explain it to other people—because they haven’t got any frame of reference for you, you haven’t got any frame of reference for them, and it’s all just a muddle. But I guess that’s what the world’s like, and it’s just an interesting time now because everybody’s speaking a different language from their own epistemology, from their own ways of knowing, that they’ve gotten confused with their ontology—their ways of being. They sort of mix these things up and everybody’s clamoring, speaking all at once from these things and demanding to be heard, a.k.a understood, a.k.a someone’s gotta stand in my shoes, but not you—you can’t have my shoes! [laughs] It’s all really weird. People are in bad relation. So that’s the thing, bruz, that’s what we can talk about for the next forty-five minutes. And the big theme is, how do we bring ourselves and the world back into right relation before it’s too late? Well, not before it’s too late, after it’s too late. Now that it’s too late, [laughs] how do we bring everybody back into right relation?

EVDo you think it’s too late, Tyson? I mean, this is a question I was going to ask you later on in the interview.

TYIt’s too late to return to any kind of homeostasis with the systems that we have now, which are on their last legs. It’s too late to reset or stabilize the global systems. And I’m talking climate, the biosphere, everything that people regard as natural. And that’s another thing we don’t have [in Aboriginal culture] is this distinction between natural and unnatural. So nature for us is just everything that is. So that includes economic systems, supply chains—all these things are nature as well. So you look at those and it’s the same thing, because as the biosphere sort of breaks down, the biota breaks down and gets in increasingly chaotic states—it will tend towards order again, but it won’t be the same order. New systems will emerge, and you’ve gotta be excited about that, you know, if you’re looking at the big story, big picture arc of the world. It’s not coming back, what was there before. It’s not gonna be able to be held onto, what we have now. We are in for a rocky ride. And I guess we look at what emerges from there and from that, and then figure out how we come into right relation there in order to hopefully retain some kind of role in the next system that emerges globally. Because if we can’t retain the role of custodians, then, well, I mean, we’re gonna have to humbly submit to, you know, porcupines or whoever it is that takes over.

EVWell, coming back into right relationship, which is what you explore in Right Story, Wrong Story in depth, you know, you talk about time and place and you talk about these different systems of Indigenous knowledge, which can be of use in, I guess, bridging between now and the future. And this relationship to place and time seems to be a central one of those. As you said, there’s no distinction there between those terms in your language—obviously in English there is, and maybe that distinction is part of this challenge?

TYWell, some of us are grappling with this. We’ve started changing the language, you know, and have this sort of different code that tries to make English do what our language does, but more, because there’s a kind of self-consciousness within it. So the new English terms—we sort of hyphenate words and jam ‘em together, like “place-time.” We talk about, you know, I’m in this place-time, or in that place-time, and we’re talking about a seasonal moment, but in a particular regional location, et cetera. You know, we cobble these together. And even the idea of pronouns—because there’re pronouns in our languages that don’t exist in English, so there’s not just us, but there’s us-two, us-only, us-all, et cetera, like that. We put these together, but they’re kind of self-conscious in the way they’re put together; in the fact that they were needed to be put together in this way, you see that they’re trying to describe something that is not understood by the decoder of the word. It’s kind of in it—you can see that self-consciousness. So anyway, there’s a few of us trying to put that together: “place-time,” “time-place.” We’re hyphenating words and starting to use those instead. Because it kind of demands of people, if you are asking them what time something happens, it demands that people are thinking about the place where they are and what’s gonna be going on there.

See, we stuffed this up. We messed this up, bruz, because we didn’t think about things relationally when we booked this interview. We booked this one for 10:00 a.m. Ten a.m is perfect because I finished dropping the kids off at school, or setting them up and taking care of them, getting them all ready. One of them is autistic, one of them is ADHD, so it’s a big mess. And that will give me like half an hour to sit down, prepare, get ready, get in the right headspace. But we booked it for that time-place, not for this time-place. For this time-place, like the day before yesterday, daylight savings started, and so all the clocks went back an hour. So this morning I wake up into the middle of a nightmare, where I have to set up for this interview at 9:00 a.m., and I haven’t organized that. Things have shifted on the calendar. Where the calendar a week ago said 10:00 a.m., now it says 9:00 a.m., and I’ve gotta try and get somebody to take the kids to school and then someone to look after the little fella who’s like, you know, an autistic six-year-old who’s like the size and strength of a pit bull, you know, [laughs] and who is very hard to manage. I gotta, at the last minute, set that up. So we didn’t organize. We booked according to time; and time is bullshit, because time doesn’t account for all your relations with human and nonhuman. It doesn’t account for your relationship with seasons. And even with the broader systems of civilization, like clocks and calendars and different time zones and changing time zones seasonally—we didn’t think about that. We just thought about, hey, yeah, we want to talk, and we can click this blue square on the calendar and it’ll all be taken care of. Well, it won’t, because we didn’t think about time-place [laughs].

EVRight. Time’s an imposition in that context.

TYAnd it’s not time-space, like Einstein—it’s time-place because place has meaning, you know, place is specific. Place is specific seasonally and regionally and in a million ways; it has story, and it has meaning—all the special places there. It has your maps of meaning on it, your travel roots and what they mean to you and how you store your knowledge in that. Every human being’s got that. Even the worst people in the world still have a remnant of that, you know? I don’t care if your ancestors going back ten generations have been living in cities or towns—you’ve still got that. And that doesn’t go away, because that’s what human beings are. We are like: I’m located, therefore I am.

EVWhen I was researching for the conversation with you today, I came across a conversation I think you had online awhile ago about deep time. And you were speaking about the relationship between time and place, kind of bringing up some of the things you’ve just shared. And you said that “as beings we are in processes, in a landscape that is a process as well,” and that there are these cycles of time that are part of these processes, that there are “lots of circles running at once. Everything is going.” I was really struck by that. And it seems to echo what you just talked about—that there are these processes interlocking that are in relationship to place and not part of some sort of imposed construct.

TYIt’s weird. Object permanence becomes a bit of a problem when you self-apply it inwardly, you know what I mean? It’s really tricky. Look, this is part of this sort of childish fascination. People don’t really get past it in young cultures. There’s this terror in the moment that you figure out that you’re gonna die one day, and that everybody around you is gonna die. It’s a really hard thing to deal with for a little while, you know? But usually we have initiations at around the age of fourteen, thirteen, as human beings that get us past that, that make us go into that fear, and find out and realize why that’s not a problem in the cosmic order of things. So that’s the problem there, I believe.

You know, we want systems to remain stable and as they are forever. And they just don’t, and that’s what emergence is. Systems break down, they undergo phase shifts, and during those phase shifts new systemic orders and dynamic relational sets emerge within these systems. You end up with these forces of destruction rampaging around the system, but then that gives rise to other things that balance that out and are gradually supposed to bring things into a state of stability.

EVOne of the things you talk about a lot in the book is technology and how that relates to deep time and many other things. And you spoke about how technology consistently butts up against deep time, whereas traditional ecological knowledge doesn’t, in part because design and innovation often doesn’t emerge from that place of right relationship or right story, which you’re talking about. I wonder if you could speak to this?

TYYeah, well that’s the idea of TEK: traditional ecological knowledge. So it’s TEK, in that way, but then there’s tech, T-E-C-H: technology. See that’s a weird thing—so at the same time as there’s this desire to maintain system stability indefinitely, there’s also this insane need to make things better. But in this industrial civilization, that idea is through tech, T-E-C-H, that improvements can be made rapidly, and that it needs to be constantly updated, and constantly improving, because the innovations that you create break down really fast and so they need to be replaced. It’s the same as the economic system: you need constant growth in order for it to even function, otherwise things fall into recessions and depressions and all the rest. So in a sort of a tech-driven—T-E-C-H—you don’t have that relational accountability of TEK. TEK demands that any new innovations have to be accompanied by an appropriate and effective social or psychological technology that comes with the physical technology, that can ensure that that new tech can never be weaponized and scaled to destroy the entire society and that environment or bioregion or whatever. So traditional ecological knowledge makes sure there’s a psychotechnology and good lore, good story, that can be permanent and that can ensure that thing is never gonna wreck everything.

Sometimes it’s an affordance that’s built into the tech itself to limit it, which is a really weird thing about Indigenous technology. Like in our culture, we have these massive swords that are made out of sawfish blades. They’re huge and bristling with these teeth sticking out of this massive sword. You could cut a man in half with that, but there’s a tiny little three-inch handle on it, and that’s the affordance that’s built in that can allow you to have a spectacular battle, but you probably couldn’t kill more than one person with it, you know what I mean, so it’s not a massive sort of massacre ever. That’s how we stop imperialisms from happening—it’s all built in affordances into our tech. So that’s the idea of making things sustainable, making things last for a bit longer than they otherwise would.

EVRight, so traditional ecological knowledge only allows you to scale within the limits of your relational obligations.

TYThat’s it. So you are not hastening the big phase shifts or deaths of a system, you know? You’re not doing that, because you’re a custodian. You’re supposed to maintain it as it is for as long as it’s supposed to be maintained.

EVWell you talk about the need for deep time diligence in your book, and the question of whether we can innovate from a place that is in relationship to deep time, and what possibilities such innovations would open up—and this seems especially needed as the climate is shifting and everything’s changing. And yet it’s often not even secondary, it’s tertiary at best, in the forefront of these innovative ideas that people put forward to try to respond to what’s happening.

TYMm. I think I put a disclaimer in there, or a caveat, that there’s a difference between a deep time diligence and prophecy.

EVWell, how would you describe the difference?

TYWell, I think for a start, prophecy’s bullshit. Deep time diligence is sort of looking at all the systems and the trajectories of these things and doing catastrophic risk analysis, doing all these kinds of things, doing these things collectively. So as a group, everybody’s out there observing what’s happening in nature and what’s happening in your economic systems and communities, and we keep coming together and everybody’s bringing a different data set, and some of these overlap, some of them are contradictory. But in the aggregate, we get a sense, together, with that one big brain—the computational power of a group of people together, you know, big community together doing all this work—that, that works. That’s deep time diligence, because you start building the stories that you need and the Lore that you need and the knowledge that you need for the system as it’s shifting.

And you make sure that you’re moving where it’s going to be, where the authority is going to be, where the livability is going to be, and how it’s going to be. You’re constantly shifting towards that while you’re testing the water, testing the water, testing the water, the whole time, just ahead of you. Like when you’ve got a stick in a stream, and you’ve got that stick ahead of you, and you’re testing the depth—kinda like that. Whereas a prophecy is like standing on the riverbank and saying, “There is a giant hole in the middle of the river right there. I can divine it with my special magics. [laughter] And at the bottom there is a troll protecting a pile of diamonds.” You know, prophecy is gammon, it’s rubbish.

EVWell, going back to psychotechnology, which is something you talk about—I really loved how you described the way that we have to store data safely in the long term, and how that’s through relationships. And in some ways it’s really simple and essential when you hear that, but it also seems completely revolutionary in our current tech era and how we conceive of data and its role in the future. You wrote that “the key to keeping track of stable innovation processes across multiple generations is story.” You said—I love this quote—“that it can be more creative than a Cambrian explosion, or more destructive than a nuclear explosion. Story that maintains the continuity of creation requires a lot more work, however, and it develops over time from thousands of data sets held in relationships.”

TYYeah. So we’ve got a couple of different things in place to back up this yarn that we’re having, you know, the digital data that’s created from this yarn. We’ve got a couple of different things in place to back it up. But it’ll be gone. I’d say that like in a few decades this won’t exist anymore. Data is constantly deteriorating. Systems are changing because the T-E-C-H tech is moving so fast and there’s obsolescence cycles that are just getting tighter and tighter all the time. Data is vulnerable. Data just disappears. All your photos in Photobucket—how long are they gonna be there for? Is someone just gonna maintain that server forever, and maintain the costs for that, and keep losing money? Nah. So the only way to store data long term, like proper long term, is in intergenerational relationships, where data is stored in narratives, intergenerational narratives. That can last for forty, fifty, sixty thousand years. That can last as long as relations are continued—that data will last. It’s the only safe way to store data in the long term. And like you say, a revolutionary idea—it probably is, you know? I didn’t think of it like that when I wrote it. It’s true though, eh? That’s the only way to store data in the long term.

EVWell, there were a lot of interesting notions that stuck out to me in Right Story, Wrong Story, and this one really hit me, which was you talked about how every viewpoint is ignorant really in one way or another, but that “combined over time, in right relation with and across generations”—as you were previously speaking about—“these diverse ignorances create right story,” that all those weaknesses together form something that’s very, very strong that can stand the test of time.

TYBecause collectively, if you imagine it, you’ve got all these little story particles banging together in this big collider, so they’re testing each other on each other, but in this big complex kind of mess. And order emerges over time in there. Everybody’s sharing their different ignorances. Your ignorance is only from the fact that you have a valid data set, but it’s only from one standpoint. But you get all the multiple standpoints and you start to form a picture. You’ve got all these different data points coming back in and it’s computed, like you’ve got dark data processing happening at this big collective level with the best computation mechanism ever—’cause the human brain’s pretty good, but you get like twenty, thirty, a hundred and fifty of those brains together, sharing stories, sharing data sets, and then all of these things just kind of moving and shaping together, something emerges: principles, lores, story, narrative binding all these together. That’s why myth works so well. That’s why myth is so evocative and so enduring; it’s because all these diverse ignorances come together and truth emerges from that, from all those different data sets. Because the ignorance is just that: you’ve only analyzed it from one point of view. But collectively, collective analysis—ah, that’s amazing. That’s the only way it can be done.

EVBut you write about wrong story, also, as this other piece of all this, which you say is “unilateral and immediate; it does not stand the test of time.” It does not evolve from these collective data sets to be something that is correct or right or can help create a story that allows people to be part of something in the long term; it is deployed as something as disruptive as, you know, you talk about propaganda, disinformation, dating app profiles. You give us all these examples that dominate and obscure the many voices that make up right story.

TYNice. [laughs] I forgot that I wrote that. So you think about all these diverse ignorances, all coming together to create right story, to create something sublime, to get an idea of a reality. Because your ontology, like what is real, is reflected back then to you, okay? But then you look at wrong story. Wrong story is where instead of all these diverse ignorances coming together to make truth and reality, instead of that, it’s like a small cluster of those ignorances, or just one tiny data point of that ignorance decides: I am truth. I am right. And I’m gonna insist that just this point of view is the right one. And I’m gonna recruit as many people as possible. And together we’re gonna create a compelling narrative, usually a spiritual narrative, straightaway, you know? We’re just gonna draw on mythological tropes from right story everywhere. We’re gonna draw on even proper facts. And you can fact check this—every fact’s gonna be true. But we’re gonna selectively pick those facts and make them fit this narrative. And then we’re gonna project it and we’re gonna insist on it and we’re gonna die on that hill and we’re gonna insist that everybody follow this narrative to the death. And that’s what we’re up against. That’s your wrong story. It’s really powerful because it’s incredibly ignorant, and it’s a way that a minority can subvert and control a majority. It’s a brilliant leverage point. It’s a brilliant psychotechnology. It’s probably the most brilliant invention ever made: the wrong story. Because story is so powerful: story can heal, story can kill. Right story is clunky and it takes time—because it’s supposed to take time.

EVWell, I actually found myself really taken by the simplicity of some of the ideas that you’re putting forward in the context of a very complex system that doesn’t like simplicity and says simplicity is bad. And one of the things you talk about is the power of memory. You talk about how “cultural knowledge of a region is not just contained in the tribe’s living memory and the sentient landscape, but is also in an enormous continental permanent ledger, in which each place keeps the Lore of other places,” and this expansive notion of memory, in the context of time-place, again, seems like an important point.

TYYeah. Oh, well, that’s that big governance model of all this sort of nested, fractal relations and connections of authority. They scale up from every pair, to every pair of individuals, to every pair of clan groups, and then to every four clan groups, then pairing off against each other: and that’s a tribe. And then every pair of tribes coming together and forming a region, and then every pair of regions—and so it keeps fractally scaling up, you know? So that’s our governance model there. And that’s kind of beautiful, and within that there’s Law, L-A-W, and there’s L-O-R-E. And Law is almost like a physical substance in the land. It’s a permanent ledger where the Laws are. They are inalienable, and, well, they last as long as landforms last. So they’re not permanent, but they last for a pretty damn long time.

EVRight. You said that, “This system makes our cultures anti-fragile and acts as a kind of insurance against disasters—the Lore and therefore the Law of any culture can always be restored.” I felt it’s like a time capsule insurance for the future.

TYIt is. Because there’s volcanoes and shit changes, you know? There’s earthquakes, there are rising sea level events that happen, and there are tsunamis—like shit happens. Sometimes there’s a red tide. So, you know, everyone’s eating fish for a couple of weeks out of the sea and they don’t know that they’ve all consumed a poison that’s gonna kill every single person in the whole tribe, you know? Shit like this happens. So you make sure that your Lore is actually kept with other tribes. So there’ll be a few people in another tribe who carry all of your Lore and language and everything else, so if your people get wiped out, that can be repopulated from the other tribe, and that Lore that’s necessary for caring for that landscape and that bioregion—that’s carried on there. So that’s that anti-fragile permanent ledger human network that goes on.

It comes back to this idea of being able to maintain a reality, like an actual empirical reality. And there’s that idea again of all those little wrong stories coming together to make a right story, you know what I mean? Like your individual viewpoint—that’s not a reality, that’s a truth for you. And if you’re doing it right, then you’re constantly changing that truth and amending it according to your interactions with others and other truths. Because that truth—that’s your epistemology, and your epistemology is supposed to be a method of inquiry where you’re constantly changing and updating your worldview according to the other data sets that you’re coming across with other people’s story. So that’s your truth, and that has to be constantly changing. But then your ontology—that’s your reality, and that’s different. Because the reality is empirical and it’s collectively discerned. You need many people to help you discern that and you discern that together. That’s what’s real. But truth—that’s a different thing. And people get those mixed up in young cultures, especially Anglophone cultures. There is a mix up between the idea of truth and reality. Truth is elevated above what is real. And the person with the loudest voice, and who employs the most persuasive, logical fallacies, they can convince everybody of a truth. They can convince people that their truth is the reality.

EVWell, you talk about the reality of what’s unfolded in your cultures over the last few hundred years, and how so many peoples in your land are prevented from implementing Indigenous governance; putting the Lore that is held into practice is limited by the systems of oppression that surround you—let alone in the land, you know, the struggles there. And you said, “We simply keep the Lore alive in memory and ceremony, and wait for a time we can begin living again.” When and how do you see this happening? Do you think it’s gonna be able to unfold within the systems that are currently present, or are they going to have to fall away?

TYWell, people like you and I are living in the wrong story of hope. I guess the only reason we’re having these conversations, the only reason we’re writing these books, is because we are hoping that there’s a possibility of a soft landing, where billions won’t have to die in horrible ways, where children won’t be harmed, won’t starve, won’t burn. We’re all hoping for this, and it’s probably wrong story because it’s probably not possible. The probability is that, you know, the systems change is and will continue to unfold in ways that are fairly catastrophic. Most of the people in the world right now are really feeling it, and are really in Armageddon, and in incredible suffering and upheaval and fear and death and all the rest. That’s most of the people in the world. You and I don’t notice it, because we’re living in these first world countries. It’s like, most of the world’s already burning, man. We’re past the tipping point. Probably need to start putting together the cautionary tales that are gonna carry everyone forward into the future and make sure this shit doesn’t happen again. With whatever stable system emerges from this, it probably won’t emerge in nice ways.

EVWell, one of the things that comes across loud and clear in your work is your lack of love for the spiritualizing of Indigenous wisdom and the spiritualization of a lot of things that are skin-deep, to say the least. You said, “You’re not going to find your way through this mess in drum circles and sweat lodges, or any other weird co-opted bits and pieces of native culture that enable spiritual bypass—chanting and vision questing and tripping balls to avoid the hard feelings that come with being authentically grounded in your shitty context. We have to look past the sexy and inspiring stuff and step up to our fear and uncertainty, before we panic and turn into a seething mosh-pit of fast zombies.” I love this, because I feel like the importance of stepping into the fear and uncertainty is at the center of the narrative that we are being asked to step into. But it’s very, very disarming for people, and they’re holding onto the narratives of the past, rather than stepping into a space of unknown, as the narratives for the future; the right story is saying we have to behold what’s unfolding around us. We have to take stock.

TYI don’t know. I think that’s part of an instinct to reach into some Lore, some L-O-R-E, you know. I need story. I need story for this. I need stories of upheavals and faith shifts and to know, how do we transition? What do we keep, what do we take with us?

EVWell, I guess I have one last question for you, maybe to end this conversation that we’re having and it is about the future, which you’re talking about just now, and also the past. Because you wrote about the danger of idealizing the past, or a mythical future, and that when we do so, “we miss our chance to engage with right story in the present. Cultural longevity is important, but living cultures must always adapt to current contexts and remain fluid enough to allow for continual emergence. No entity is immortal.” We have to change, we have to shift.

TYYeah, that’s it. I think you just said it. Everybody longs for permanence. What’s ironic is that we did manage to maintain quite a bit of permanence, you know, for at least ten thousand years at a time, holding systems stable. We went through about two ice ages, two, maybe three ice ages, here in Australia. We’ve seen big, massive climate shifts and different shifts all over, and like Victoria, here where I am—that’s an incredibly volatile landscape. There’s been volcanic activity that’s just devastated and disrupted everything here for as long as there’s been humans here. Victorian Kooris are like the most adaptive, most weirdly innovative people on the continent, simply because of the constant upheaval of their environment. In Kuranda, in Cairns, in far north Queensland there—that landscape’s only ten thousand years old because there was a massive volcanic eruption there that just completely changed the whole landscape, you know? So we have these disruptions happen, but we maintain, ironically, the most stable situations in landscapes, in the central desert, for example, and in many places. And ten thousand years is pretty freaking long to maintain a system exactly the same. We stabilize these landscapes and climates, and then we hold ‘em as long as we can. But ironically that means that we have to be moving around on it seasonally. So we’re not sitting in permanent sedentary communities and built environments—that’s the thing, but where we’re establishing a permanence is in the stability of our climate and bioregion. But that’s only ever as good as your neighbors, unfortunately. So make friends with your neighbors. Make sure you marry your neighbors, and like adopt your kids across—it’s the only way to sort of stop them from fucking everything up, because the guy up the creek from you, if he’s shitting in the water, then your kids are gonna get sick.

EVTyson, it’s been great chatting with you today.

TYNo worries, mate.