Shifting Landscapes Film Series Engagement Guide

Trailer

Trailer

Watch the film series’ trailer.

This Engagement Guide is a companion to our four-part Shifting Landscapes documentary film series, which explores the power of art and story to orient us amid the darkness of our time. Following a musician, a poet, a writer, and a filmmaker who are each embracing the alchemical power of story to connect and transform us, this series opens ways of being that hold both catastrophe and love as our landscapes change and disappear. Responding to great changes within their landscapes—the vanishing song of the nightingale in southern England, the desecration of a sacred mountain in Hawai‘i, a melting glacier in Iceland, and a traditional way of life threatened by development in Cambodia—they create art that can help us understand the changes beginning to affect the places we call home; and offer stories that open us to our connection with the Earth. In four corresponding guides, we invite you to explore the pathways illuminated by these storytellers and a depth of relationship with your own shifting landscape. Through spaces of reflection, discussion, and practice, each guide offers ways to weave these stories with your own; to open a dialogue and share values within your community; and to cultivate a living connection with your landscape.

Host a Film Screening

Interested in hosting a screening of the film series? Contact us at screenings@emergencemagazine.org

Engagement Guides

In The Nightingale’s Song we meet Sam Lee, a British folk singer who joins nightingales in song during their mating season each spring. As climate change and development threaten their habitats, nightingales may disappear from England within fifty years. What would be forgotten, Sam asks, if we no longer heard the call of this beloved bird? The film follows Sam’s journey of becoming a traditional folk singer; and follows him to the woods of southern England where he sings with nightingales as both an act of rebellion against their imminent extinction and an expression of love for the living world.

This film explores what it would mean if the nightingale and its song were lost from the English landscape. It draws attention to the musical vocabulary that nightingales share with humans; their influence on art; and the ancestral kinship that connects us with them—the vestiges of which are still profoundly present in our culture, storytelling, and emotional and physical understandings of certain landscapes. The film points to the irreversible implications of species loss, specifically the ancient relationships between human and more-than-human beings that could vanish with increasing rates of extinction. By honoring the ways previous generations heard the spirit of the land in the call of birds, Sam works with song and a practice of deep listening to nurture an embodied kinship with the nightingale that he hopes will lead to its protection.

This section invites you to reflect on the themes explored in The Nightingale’s Song. To engage with these prompts, you could write responses to them in a notebook, sit and contemplate them, or take them with you to a quiet outdoor space.

-

Much of Sam’s practice is rooted in deep listening. In the film, we learn that before he first sung with the nightingale, he spent years simply listening to its piercing call. Reflect on the ways this is contrary to how we primarily interact with the living world at the moment. How might you quiet your own voice and create space for more-than-human beings’ voices? How do you think listening to something with a depth of attention and over a long period of time changes your understanding of it? How can deep listening help open a relationship with birds and other creatures?

-

Sam’s work centers the nightingale in our consciousness, reminding us of all the ways we are connected with, and influenced by, its presence in our landscapes. Pick a bird in your landscape and think about how your attention is drawn to it, as well as what may lead you to be forgetful of your relationship with it. Reflect on how this bird plays a part in your experience of this landscape. Does it feed in your backyard? Do you hear its song as you wake? Imagine some ways you could regularly center these moments in your daily awareness.

-

In the film, Sam expresses that it’s only by falling back in love with the nightingale that we can actually begin the journey of its protection. Reflect on experiences where you have felt love or deep care for a more-than-human being—what ignited and sustained this feeling? How did this feeling of love influence the quality of attention you gave this being and the way you treated it? Consider what role love can play in species protection and changemaking right now?

-

Sam says that through singing with the nightingales, he has learned to be in their presence in a way that holds the concept of catastrophe together with the concept of love. What do you think Sam means by this? In what ways do you think holding this duality might affect how you respond to loss and destruction within the living world? How can experiencing love and grief simultaneously deepen your connection with your landscape?

-

Consider how Sam’s practice of singing with the nightingale is an act of devotion to the living world. How does Sam honor the presence of these birds? How is Sam in reciprocity with the beauty they bring to his landscape? Reflect on what actions help you express devotion—contemplation, silence, meditation, or prayer? Consider how you could offer a devotional action towards something that you hold dear in your own landscape.

Ahead of the discussion prompts below, feel free to share what within the film and/or Sam’s work as a storyteller resonated with you most.

-

In the film, Sam listens to the way song thrushes and robins honor each other’s space and song, calling alongside, rather than overwhelming, the other’s voice. The nightingale and Sam sing together in the same way. Discuss what we could learn from this way of listening and responding. Why does a genuine dialogue with the more-than-human world require our ears more than our voice?

-

Sam says in the film that our ancestors would listen into the spirit of the land and hear it in birdsong. While Sam notes that we collectively don’t have the same level of interpretation as we once did—“we have stopped hearing nightingale”—share what you feel embodies the spirit of your landscape, even if we are not listening to or witnessing it as we once did. How would a renewed attention for these expressions of the land deepen a sense of connection with it?

-

We learn in the film that, in our lifetime, we may hear England’s last nightingale. How might knowing that we could lose this creature from this land change our recognition of its presence? How does this awareness affect our appreciation of it right now? Should the nightingale disappear, what is the extent of our responsibility as the last generation to hear its call to ensure its significance is shared with those who come after us?

-

Responding to the possible extinction of the nightingale in England, Sam asks, “How do we memorialize the passing of a species, of a song, of a being not of our own? And are we able to? Are we prepared?” Share your response to this question and discuss what it could look like to memorialize not only the disappearance of a species, but the relationships and stories that vanish with it.

-

The film explores the need for kinship with other beings to be profoundly felt if we are to embody a role of stewardship: Sam says, “You can’t protect what you don’t know and what you’re not in love with.” Share what a felt relationship means to you, and how our experience of a relationship—whether emotionally, sensorily, or spiritually—shapes how we engage with it. Discuss how you think a feeling of love can influence what our stewardship for the living world looks like?

This practice is designed to bring you into a felt experience of the story of kinship with the more-than-human world that Sam offers. Make sure you have ample space and time to allow yourself to engage deeply with each prompt.

-

Bring your attention to a bird that belongs to the same landscape as you, and whose song is present when you begin this practice—during the dawn or evening chorus will be best. Sit, stand, or lay comfortably and spend some time first focusing on the inhale and exhale of your breath, and then attuning to your senses by paying close attention to what you can hear around you. Begin to listen specifically to the presence of your chosen bird. You might hear it singing or calling, or hear the rustling and scuffling of its feet or wings. Stay focused on a feeling of pure awareness of what you can hear. Try to frame each sound as a gift from the bird—as an invitation to listen to the beauty that is within your landscape.

-

Be attentive to how the bird’s voice gives rise to emotion inside of you. Does its tone make you feel joyous? Does its call inspire melancholy? Identify the feeling as you listen and, with each warble, trill, and twitter, visualize this feeling swelling inside of you, spreading outwards from your center into the rest of your body. Take a moment to recognize how the song of this bird is affecting your inner senses—your emotions, the feeling in your heart—as well as your outer senses, and how this brings you into relationship with it.

-

From this space, seated in the emotion that has arisen, return to deep listening. Eyes closed, immersed in the sound, feel into the difference between how you were listening at the beginning of the practice and how you are listening now. How is the emotion evoked by the bird changing the way you listen to it? Are you listening with senses beyond the ears? What can you hear within the bird’s voice that you didn’t before? Why do you now want to listen?

-

Now that you have brought this creature into the center of your awareness, take some time to praise it. It needn’t be complicated or formal—it could be as simple as speaking to the bird, out loud or silently, or offering a prayer of thanks for its presence in your day. You could also express this connection creatively: write a short poem, draw or sketch the creature. Another way to honor it is by sharing your experience with a friend, bringing the creature into their awareness too. What matters most is that the praise acknowledges and celebrates the growing relationship between you and the bird.

In this film, Native Hawaiian poet Jamaica Heolimeleikalani Osorio invites us into the Kanaka Maoli (Native Hawaiian) concept and practice of aloha ‘āina—a love for and of the land. The film traces the ways aloha ‘āina flows through the themes, intention, and delivery of Jamaica’s poetry, her work in defending and restoring the sovereignty of Kanaka Maoli, and her involvement in the movement to prevent a thirty-meter telescope from being constructed at the summit of Mauna Kea—the most sacred mountain in Hawai‘i.

This film examines how the concept of aloha was appropriated, commodified, and severed from its essential understanding of people and land as part of the colonization of Hawai‘i, and how people and land continue to suffer when Western ideas of progress are imposed upon Indigenous lifeways. The film looks at the intimacy between people and place that emerges when a love and gratitude for the land bridges together a culture’s social, intellectual, and spiritual frameworks. Through poetry that helps both the speaker and listener understand the ways they are connected to each other, and to the land that sustains them both, Jamaica envisions and articulates a promise of guardianship for any land that has fed and held us.

This section invites you to reflect on the themes explored in Aloha ‘Āina. To engage with these prompts, you could write responses to them in a notebook, sit and contemplate them, or take them with you to a quiet outdoor space.

-

In the film, Jamaica introduces us to aloha ‘āina—a cultural principle and practice of love for and of the land that is central to Native Hawaiian cosmology. How does aloha ‘āina resonate within the framework of your own worldview? In what ways do you feel love for your landscape? What has led you towards, and helped you nurture, that feeling? How does this concept help you understand the importance of having the spiritual relationship between people and landscape centered within culture?

-

Jamaica shares the belief that any place that has nurtured us is sacred, and aloha ‘āina is the recognition that we should respect that and act accordingly. Consider the ways your landscape provides for your well-being. How does it care for you physically and feed you spiritually? What elements of this relationship feel sacred to you? Jamaica also says that “when we love the land and we are connected to the land, She teaches us how to love each other better.” How is your treatment of the land linked with how you treat people around you? Why do you think these are reflective of each other?

-

We learn in the film that visitors to Hawai‘i often talk about feeling something special there. Jamaica says that this experience is actually ‘āina (land) still trying to speak to us, because the sacredness of this land has not been forgotten as it has in many places around the world. Think about a time when you felt a special feeling-quality within the land or sensed something sacred or transcendent in a place. How do you think the land might have been speaking with you in that moment? Did this experience change the way you saw the land? How did it shift the way you engaged with it?

-

Consider how Jamaica’s poetry is a form of activism. What do you feel her poetry brought to the movement to protect Mauna Kea? What can poetry offer to people and land that other forms of traditional activism cannot? How did her ancestral relationship with the landscape allow her to realize that the inspiration for her poetry came not simply from within her, but from a deeper source and was a gift from the Mauna itself?

-

Jamaica speaks about the power of the imagination to transform dominant and destructive ideologies. When we dream, envision, and articulate a different way of being, we take the first steps toward making it real. She goes on to say that it’s not well-worded arguments or data that change this imaginative space, it’s the resonance created by the right poem or the right song. Reflect on a poem that you have heard or read that opened you to an imaginative space where you could contemplate and envision a way of being that is different to our current dominant beliefs and ways of being. What impact did this have on you? Did it help you see beyond ideologies that seem rigid or unwavering? What different way of being were you able to glimpse?

Ahead of the discussion prompts below, feel free to share what within the film and/or Jamaica’s work as a storyteller resonated with you most.

-

Jamaica says aloha has been transformed from an idea and practice that is rooted in the land and people’s relationship with it to a word that has been oversimplified so that it can be marketed and sold. Discuss how the commodification of words like “aloha” or practices like hula by colonial societies impact the integrity of their purpose within Indigenous communities. How does the spirit of aloha ‘āina help reawaken and reclaim Indigenous sovereignty, and challenge Western notions of property, ownership, and progress?

-

Unpacking the dominant narrative around Hawai‘i’s colonization, Jamaica warns against the danger of a single story of “history and progress, from savage to paradise tourist destination, with no gray area between that.” Discuss the harm of this story. What has been omitted and erased? How does this story shape how we collectively see and engage with Hawai‘i today? How has this story impacted not just the people of Hawai‘i but also the ‘āina?

-

In the film, Jamaica contemplates how she can tell stories today that create a cultural continuum for the future, and that also include the new and very different experiences of colonial occupation that younger Native Hawaiian generations are experiencing. Discuss what you think poetry opens within us that speaks across generations and experiences. What is the importance of poetry or stories that entwine the cultural experiences of generations past, present, and future, particularly when our physical landscapes are changing or threatened?

-

Jamaica shares that she has a pilina (an intimacy) with her history which shapes the way she experiences the present in Hawai‘i. She says this connection comes with a responsibility to not lie idle when her home is depicted and imagined in an irreverent way. Discuss how a relationship—whether ancestral or newfound— with the history of a landscape influences a sense of responsibility for its present and its future. How is this idea an extension of aloha ‘āina?

-

A revelation of the Mauna Kea movement, Jamaica says, was the understanding that the mountain was far more powerful than anything we could protect. Ultimately, the movement recognized that the mountain was the apu (the water basin) or container that brought together and held the community’s aloha for the land and for each other. How is aloha a form of resistance against development and destruction of sacred lands? What is the importance of reawakening a love for the Earth at this time of ecological unraveling? When we recognize this love, how can we work with it and offer it back to the Earth?

In Aloha ‘Āina, Jamaica says the work of her poems is to help the speaker and the listener understand their relationship to each other and their relationship to the place they stand in that very moment. This practice is designed to explore this idea. Make sure you have ample space and time to allow yourself to engage deeply with each prompt.

-

Equipped with a notebook, head outdoors to a place that holds personal significance for you. It could be a space that holds special memories for you, or a place where you feel in close connection with the land. Once you arrive, spend some time sitting or walking quietly through this place, letting your body and mind become fully present there by paying attention to the rhythm of your breath and orienting your senses to the sights, sounds, and smells around you.

-

After a while, begin to focus on how this place nourishes you. Consider what it offers you physically (e.g., do you eat produce from this place; does it provide you access to water, sunshine, or a place to exercise or relax?), emotionally (e.g., does this place inspire creativity, happiness, a sense of peace?), and spiritually (e.g., do you sense something sacred here; does this place bring you into relationship with something larger than yourself ?). In your notebook, log as many of these gifts from the land as you can think of.

-

Opening to a new page in your notebook, start jotting down the words, phrases, and images that come to you as you become present in this place. If you feel stuck around language, what comes to mind when you think about the feeling-quality, smells, sights, and the past and possible future of this place? What feelings arise in you when you think again about what the land offers you? Using the language and images you have just evoked, take some time to write a poem. It can be long or short and can follow any structure that suits. It doesn’t matter if you don’t deem the poem to be “good,” the purpose is simply to articulate a gratitude for, and connection with, the land.

-

Once done, share your poem with a friend who is familiar with the place you’ve written about. Prompt them to express how the poem connects them in new ways with both you and the place the poem is centered on. Share with each other what the poem affirms and alters about your perception of this place.

-

Jamaica also says in the film that “the composer, the artist, never owns their composition. The song or the poem or the chant belongs to that which it was composed for.” One way to reciprocate the inspiration and nourishment that the land gave you in the writing of your poem is to offer the poem back to the land. You might do this by returning to the place and reciting it or offering it to the land in prayer.

As storyteller Andri Snær Magnason puts it, climate change is like a black hole: so big it’s larger than language. We understand it not by looking straight at its center, but by looking at its edges. In The Last Ice Age, Andri retraces his grandparents’ annual spring pilgrimage to Iceland’s Vatnajökull glacier, searching for the stories that lie at the edges of our climate crisis in both scientific data and his family’s memories. Witnessing the inevitable decline of Europe’s largest ice cap with his son Hlynur, Andri pulls on the ties of love that connect generations to try to grasp what the immense changes he has seen in just one lifetime will mean for the future of the planet.

This film explores how we can begin to properly understand the scale of transformation engulfing the Earth; to comprehend the impact of glacial ice melt, shifting Arctic landscapes, and significant sea level rise on the coming generations. Andri acknowledges the limitations of data and scientific projections to evoke empathy, and thus action, for the future and looks instead to the way stories and relationships can hold a personal resonance that links generations together. Understanding myth to be both a universal tool of connection and a format through which we can process vast questions and concepts through archetypal images, Andri shares the stories that bind him to his Icelandic landscape in the hope they can help us fathom the ways humans are radically changing the face of the Earth.

This section invites you to reflect on the themes explored in The Last Ice Age. To engage with these prompts, you could write responses to them in a notebook, sit and contemplate them, or take them with you to a quiet outdoor space.

-

Andri says that the issue of climate change is so big, it is larger than language. What do you think he means by this? Why do you think there is a disconnect between the reality of climate change and our ability to effectively communicate about it? What elements of climate change are most difficult to convey through words? What language, metaphors, or images would you use to try to encompass the scale and possible impacts of climate change? What is this language able to effectively express? What does it not manage to communicate?

-

Myths help people grasp reality, offering images that can “explain the bigger picture,” says Andri. In the film, he shares stories of his grandparents’ many trips to Vatnajökull glacier as well as the Ancient Greek myth of Prometheus to make sense of what he is witnessing in his landscape. How did these stories change your own understanding of glacial melt? How do these myths make the complexity of climate change more relatable or tangible? What are some other stories—cultural myths, family stories, or personal experiences—that have helped make climate change personal to you?

-

Andri shares that throughout Icelandic history glaciers have been perceived as eternal elements of the land—“they had always been there, and it felt like they would always be there.” What is something in your home place, or in a landscape you are deeply familiar with, that you thought would be everlasting but that is beginning to change, shift, or disappear? Are you able to comprehend what the future of this landscape will be like as these changes deepen? What helps you make sense of the reality and impact of this transformation?

-

To understand what the melting of Vatnajökull glacier means both for the nature of that landscape and for humanity as a whole, Andri says we have to look at how this change will affect us personally and collectively; we have to look at the glacier’s past and its future, and the science and the mythology surrounding it. Reflect on another change, minute or significant, that you have witnessed within your own landscape. Consider the change from each of the six perspectives Andri points towards. What depth of understanding are you left with?

-

Andri’s close relationship with his grandmother, who lived to be ninety-eight years old, allowed him to understand long spans of time differently. How does thinking about a hundred years through the lens of a personal relationship shift your perspective of the past and future? How do Andri’s familial stories allow you to see the glacier as more than just a changing landscape, but also as a living part of a history and identity that is shared between people and the Earth? In what ways does this personal connection create a sense of continuity and responsibility for places across generations?

Ahead of the discussion prompts below, feel free to share what within the film and/or Andri’s work as a storyteller resonated with you most.

-

Andri says that if scientific data isn’t translated into stories, the paradigm shift needed to navigate the catastrophe of climate change won’t occur. Discuss what it is that stories can hold that data cannot. How do stories infuse meaning into the data-led narrative of the climate crisis? Andri also asks, how do you write about something that is larger than language, suggesting that perhaps one has to understand beauty and poetry and love. Share what role you think these elements have in communicating about the climate crisis.

-

Andri says that the rapid ice melt of the Vatnajökull glacier is not just telling the story of the glacier itself, it’s telling a story of a planet that is going out of balance. Beyond the changes to this landscape, what does the melting of this glacier tell us or symbolize about the Earth and our relationship with it? Discuss how Andri’s own storytelling about this glacier’s disappearance—his grandparents’ accounts of their relationship with this landscape and his own visit there with his son—helps you comprehend the bigger picture of glacial ice melt.

-

In the film, Andri highlights that we collectively struggle to empathize with future generations—“when a scientist says 2100, we don’t feel anything.” Discuss whether we are responsible for what happens in one hundred or even one thousand years. Why does empathy often feel limited to only the immediate future? How does the inability of language to fully encompass the scale of climate change’s impact on the future affect our sense of ethical responsibility around it? How can storytelling play a role in awakening an empathy for both future generations and the future of the Earth Herself?

-

Witnessing the change that is occurring in Andri’s native landscape is an important part of his work and was also a part of his grandparents’ relationship with the Vatnajökull glacier. Discuss what you feel is important about bearing witness to increasing loss and also enduring beauty amid ecological unraveling. What do acts of bearing witness offer the Earth and us in this moment? How does bearing witness go beyond mere observation to become an active, emotional, or ethical relationship with your landscape?

-

Andri says that our moment of ecological transformation is not only comparable to the greatest events in world history, but also in geological history. Our planet is undergoing a fundamental shift in what it is, and “that is a creation story or a destruction story.” Discuss what emotions and thoughts arise in you as you contemplate how we are, through our collective actions and beliefs, changing and harming the very nature of the Earth. Share how your perception of climate change shifts when it’s framed as a destruction story, and then a creation story. Can it be both?

Make sure you have ample space and time to allow yourself to engage deeply with each prompt.

-

Sit down with the oldest person that you know with the intention of having a conversation. This could be a parent, a teacher, a friend, grandparent, or local elder—all that is important is that you have a personal relationship with them. Make sure the person you are talking with is comfortable. If you don’t know already, find out the year they were born and what age they are right now. Invite them to share what they know about the year they were born—any significant events, local and global, and also any personal circumstances. Ask any questions that allow you to get a good mental image of this year in your head.

-

Invite this person to share some stories from their childhood, prompting them to describe what life was like during this period. What did they do for fun or adventure? What are some of their most significant memories during this period? What were the social, cultural, and environmental issues and crises of this period? How did these affect their family or community? What was their understanding of climate change? Ask them to describe the landscape they grew up in. What was their relationship like with this landscape and how did they engage with it? Consider if this period feels like a short or a long time ago to you.

-

Calculate in what year you will become the same age that this person is now. Hold that date in your head and try to imagine what the world will be like in that year. What do you predict your life will be like? How will your home place be different? How do you think climate change will be impacting your landscape? What do you imagine will be some of the largest issues facing your community? How do you imagine your society will be responding? Does this date feel like a short or a long time away to you?

-

Think of the youngest person that you have a personal relationship with—perhaps your child, or a relative, or the child of a friend. Calculate in what year they will become the same age as the person you spoke with at the start of this practice. Conduct some research on what scientific data is predicting life to be like in that year, particularly environmentally. Can you fathom it? Does this year feel like a short or a long time away for you? How about when you compare it to the span of time between this moment and the childhood of the eldest person you know? Does your relationship with this young person help you hold empathy for this predicted future?

-

Taking this practice outwards into your life, stay present with the sense of intimacy with the past and the future that has been awoken by the personal relationships you have with different generations. As you make ethical and practical decisions that affect your landscape, and possibly its future, keep these relationships and your sense of empathy in your consciousness. See how it shifts and softens your way of being in relationship with this moment in time, the future, and your home.

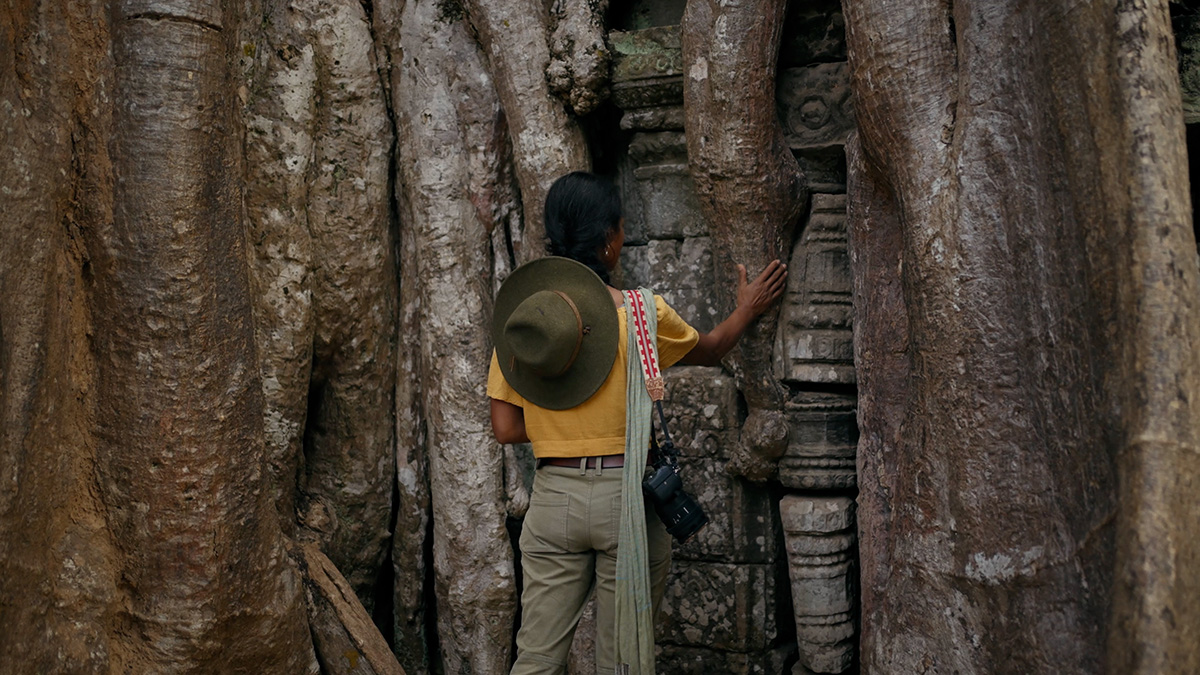

Since fleeing Cambodia with her family during the Khmer Rouge regime, documentary filmmaker Kalyanee Mam has spent much of her life searching for a rooted connection to place. This film traces her experiences of becoming displaced from Cambodia; assimilating to life in Stockton, California, in her childhood; connecting to her origins through language and food; and telling stories through filmmaking of people who are suffering disconnection from land because of conflict, development, and industrialization. Taste of the Land ultimately follows her to the landscapes of Cambodia—which have been changing through deforestation and urbanization—where her tender documentation of the disappearing, relational ways of life that these places have held has led her deeper into spiritual relationship with her homeland.

This film asks how we can find a sense of physical and spiritual “home” despite becoming displaced or disconnected from our landscapes. Looking at the way landscape is intimately entwined with a sense of self, as both home and ancestor, nourishment and spirit, the film explores how stories—whether of an ancestral connection, or a connection to people still living an embodied kinship with the land—can awaken a memory of this sacred relationship. It revolves around the Khmer understanding of the word cheate, meaning both land and taste, and how experiencing “tastes of the land,” whether through food, fragrances, stories, experiences in nature, or relationships with communities, can open us to who we are in relation to place. As Kalyanee comes to know the landscapes of Cambodia this way, she realizes “home” to be an inner space, existing wherever she remembers herself as part of the land.

This section invites you to reflect on the themes explored in Taste of the Land. To engage with these prompts, you could write responses to them in a notebook, sit and contemplate them, or take them with you to a quiet outdoor space.

-

Kalyanee shares that the Khmer word for “taste,” cheate, is also the root word for “land.” She shows how a “taste of the land” is developed through sensory experiences of it, and says once these experiences become internalized, your connection with the land cannot be lost. Reflect on your own sensory experiences of a place you feel deeply connected with. Think about the food you’ve eaten there, the fragrances and sounds present there, and how your body feels in that place. How would you describe the “taste” of this landscape? How did these experiences deepen your understanding of it?

-

Kalyanee says, “When I’m there on the Tonlé Sap, and in the jungle, and around trees, and with people who live connected to these places, I feel I can be who I am without the extra stuff that we build on top of ourselves in order to survive in a technological, mechanized, and disconnected world.” Reflect on what elements within you might qualify as this “extra stuff.” In which landscapes do you feel most aligned with a sense of your truer, deeper self? How is this identity both connected to and shaped by the land?

-

We live in a time when most of us are disconnected from either our ancestral homeland, our place of birth, or a landscape that we have felt a deep sense of belonging in. Kalyanee’s story speaks to challenges faced by anyone who is removed from an embodied and sustained relationship with these places—challenges that are only deepening as the impacts of climate change and development render our landscapes unrecognizable. Reflect on what connects you to the place that offers you a sense of home, considering things like food, language, music, memories, and stories. Thinking about cultural and physical changes occurring in your homeplace, how do the things that connect you to the land help maintain a sense of rootedness amid change or loss? What new forms of “home” are you discovering in the midst of these changes?

-

Visiting Angkor Wat in the film, Kalyanee says that “these monuments will not last forever. Even culture and traditions will not last forever. No nation, no country, will last forever. The only thing that will last are the things that truly nurture us.” Reflect on what within your landscape nurtures you physically, emotionally, and spiritually. What of these feels permanent, even when the future of the landscape seems uncertain or changing? In what ways do you think a spiritual nourishment from the land will outlast the present physical qualities of your landscape?

-

Throughout the film, we witness how Kalyanee finds her way back into a spiritual and ancestral relationship with the landscapes of Cambodia through food and foraging, being present on the land, and forming close relationships with people whose lives are completely entwined with the well-being of the land, especially her friendship with See. Consider the evolution of your own spiritual relationship—newfound or ancestral—with your homeplace. What opened or is opening a sacred connection between you and your landscape? What experiences shifted your perspective on this relationship, or took you deeper into it? What does this relationship give you? How can you nurture the land in return for the gift of this connection?

Ahead of the discussion prompts below, feel free to share what within the film and/or Kalyanee’s work as a storyteller resonated with you most.

-

In the film, Kalyanee shares how she was moved by how See’s sense of self was rooted in her landscape. Begin by sharing an experience where you became attuned to how your identity was connected to the land. Discuss how the nature of the landscape you live in influences the way you conceptualize your place in the world. In today’s culture of hyper-individualism, how have our identities become disconnected from place? How does becoming conscious of the ways our sense of self is tied to the well-being of a landscape change our relationship with it?

-

Part of Kalyanee’s personal story is her experience of grief— from the anguish of her family’s displacement from their homeland to her own longing for a profound sense of belonging and witnessing of the destruction of forests, rivers, and lakes in Cambodia. Discuss how grief led Kalyanee to be open to journeying deeper into a spiritual relationship with the land. Share how grief at what is disappearing or has been lost in your own landscape, or your ancestral homelands, challenges or deepens your own connection with the land. What other feelings for the Earth does this grief lead you towards? Discuss how grief can also be a form of love and care for the land.

-

In the film, Kalyanee visits Phnom Penh and speaks with a young family who live by the side of a railway track built on top of a forgotten and filled-in lake. She asks the question: “What does it mean when a whole generation loses the memory of a place?” Share your response to this question and discuss how development and industrialization strip away the memory held by a landscape. What do you think the physical and spiritual fallout of this could be for the generations who remember the place as it was, and then also the generations to come who will not know the beauty of the landscape that once was there?

-

Reflecting on her films and the process of making them, Kalyanee realizes that rather than merely documenting the impact of destruction on Cambodian landscapes, she was also documenting a way of life that persists there—an embodied relationship with the land held by the people whose stories she tells. Discuss how sharing stories of this way of life is perhaps more powerful than simply documenting destruction. What can bearing witness to these ways of life offer us as we try to find our own way back into a different way of being with the Earth?

-

Kalyanee says that once she saw and felt how it was to live with the land, an ancestral memory of her own connection was awoken. No matter one’s ancestry, or what has been kept or lost within one’s culture, each of us holds deep within an ancient memory of what it is to live spiritually connected to the land. Discuss how awakening this memory is central to transforming our relationship with the Earth and can help catalyze a paradigm shift in our individual and collective ways of being amid climate change.

We see in the film that Kalyanee connects sensorily and spiritually with the landscapes of Cambodia through food. Her mother’s cooking, foraging for mushrooms in the forest of Northern California, harvesting and preparing food with See and Lat in the Areng Valley— these are all experiences that take her deeper into a taste of the land. This practice is designed to explore this idea. Make sure you have ample space and time to allow yourself to engage deeply with each prompt.

-

Find something that you can eat that comes from your local landscape or area. This could be as simple as buying a piece of fruit from the market that’s been grown locally or picking something from your garden. If you have experience in foraging, perhaps you can gather some berries, mushrooms, wild herbs or greens, or you can prepare a meal made from ingredients reflective of the cuisine typical of your landscape.

-

Begin by thinking about this piece of food, considering where in your landscape it comes from, how it grows or is made, and the season it belongs to. Next, as you prepare the food—whether cooking or simply washing it—focus on the sensory experience. Feel the textures, smell the fragrances, and observe the colors. Do these sensory experiences bring up any memories or images for you? Why did you choose this food—is it special to you? Did you grow it yourself? Does it feel most reflective of the food tradition of your landscape? Reflect on your relationship to this food.

-

Sit down to eat and make sure there are no distractions around you—no phones or chores or anything that would pull you away from having your full attention on eating. As you put each morsel into your mouth, do so slowly and focus on opening and activating each of your senses so that they are focused on the experience. Take several minutes to contemplate each of the following prompts as you continue to eat: What does it look like? What does it taste like? What does it smell like? What does the texture feel like? Pay close attention to the flavors: the sweetness, the bitterness, the earthiness, or any other distinct qualities.

-

After eating, take a moment to reflect. Close your eyes and sit quietly, considering the relationship between yourself and the food you just ate. Think about how it came from the land that you live on. What elements of your landscape could you sense within the food: sunlight, the color and texture of the soil, perhaps the salt of the ocean? What characteristics of your landscape did it bring to mind? How does this help you understand the land in a different way than usual? How does knowing that this food came from the land that nourishes you spiritually change the way you eat it and how it tastes? If it feels right, you may wish to offer a word of gratitude or a simple thank you to the land for the food.