Abandoned Brownwood subdivision, now the Baytown Nature Center, near Houston, Texas.

Photo by Linda Murdock

What Survives

Lacy M. Johnson is a Houston-based professor, curator, activist, and author. Her books include The Reckonings, one of the best books of 2018 by Boston Globe; The Other Side; and Trespasses: A Memoir. She is co-editor, with Cheryl Beckett, of More City Than Water: A Houston Flood Atlas. Her work has appeared in Best American Essays, Best American Travel Writing, The New Yorker, The New York Times, The Los Angeles Times, Paris Review, Orion, and elsewhere. She teaches creative nonfiction at Rice University and is the Founding Director of the Houston Flood Museum.

Feeling for the edge of change, Lacy M. Johnson walks through a wetland nature center near Houston that has reclaimed the land where a neighborhood, sunken by oil extraction and subsumed by floodwater, once stood.

“Haunted places are the only ones people can live in.”

—Michel de Certeau

Twenty miles east of downtown Houston, where Buffalo Bayou and the San Jacinto River meet, the Baytown Nature Center sits on a shifting landscape of wetlands and marshes surrounded on three sides by Burnet, Crystal, and Scott Bays. Men toss fishing nets into shallow channels while herons and egrets rummage among the grasses for crawfish. Concrete rubble forms the shoreline; beyond it, flare towers and storage tanks and distillation columns of oil refineries line the horizon as far as the eye can see.

I first came to this nature center two years ago, after a severe winter storm brought snow and ice deep into Texas and a grid failure plunged millions across the state into the dark, freezing cold for days. Hundreds died in the blackout—frozen to death, or poisoned by carbon monoxide, or burned while trying to keep warm; hundreds of thousands suffered damage to their homes. At my house, our pipes froze and burst; water poured out of the ceiling, raining insulation and sheetrock down on our heads. It wasn’t our first disaster here, or even in this house, but those days felt different, enormous—as if something had finally given way. As if after this, life would never be the same.

When the weather warmed and the power returned, we repaired the pipes and hauled the soggy sheetrock and insulation to the curb. We did the same at our neighbors’, where the children’s bedrooms had been destroyed, a closet in the primary bedroom also destroyed. We brought over food, and they offered us some corrugated plastic posters they had in their garage to cover the gaping holes in our ceiling—advertising a new gasoline formula from Shell that “Helps Your Engine Run Like New.” We nailed one poster over a hole in the hallway ceiling; it took several to cover the hole in the kitchen. Every morning that followed, I woke up changed all over again: by the posters in the kitchen, the holes in the ceiling, the sensation of having stepped just over the edge. Until one day, feeling over the edge felt normal, and so did the holes in the ceiling and the posters that covered them.

It was around this time that a friend told me about the Baytown Nature Center, and I dragged my family there one weekend afternoon. It took about an hour to drive there from our home on the west side of the city, and we argued the entire way. The children were upset that I was making them spend time outdoors when they would rather stay home and play video games. I was upset that all they wanted to do was stay home and play video games. When we arrived, it was cold and windy, but we rode bikes along the trails and walked out to the ends of the peninsula, choosing our way along chunks of partially submerged concrete. We looked at birds through binoculars and noticed the green shoots of plants, just beginning to return after the freeze. We watched a barge bring a load of shipping containers up the channel, trucks crossing the Fred Hartman Bridge. We watched fishermen cast their lines from the piers. We had a snack, took some photos, and drove back home.

This time, I am standing under the gazebo at the highest point on the peninsula hoping to get a better view. From here, to my untrained eye, the nature center looks like a thriving wetland. It is, according to the flyer we got when we paid our entrance fee, an important habitat for migratory birds. Ducks and geese gather and practice their formations; warblers sing and stretch their wings. Out in the bay, just beyond the concrete bulkheads, Forster’s terns dive under the surface of the water; one emerges with a fish in its beak.

Since that first visit two years ago, I have learned that this peninsula was once home to a luxury housing development for oil executives and their families, where stately houses lined the shorefront offering dramatic views of the San Jacinto Monument in the distance. Now the old streets of that neighborhood have become biking trails where an occasional manhole cover marks a long-filled sewer. Trees grow in a thicket around an old fire hydrant. Back in the bramble, between wetland and shore, the empty husks of abandoned underground pools fill with layers of leaves, water, dirt. Twice a day, the tide peels back to reveal concrete foundations skidding into the bay. Just enough of the past survives to show us a place that is no longer here.

I found one map from the late nineteenth century that shows this peninsula was once perhaps twice the size it is today, a long finger of solid land curling around what is now called Scott Bay. A second, larger peninsula of marshland curls around the first, and the tips of the two peninsulas almost touch Goat Island, which has long since disappeared.

Around the time that map was made, the inner peninsula, the one on which I am now standing, was acquired by a man named Edwin Rice Brown, Sr., a rancher who used the land for grazing cattle after he had failed to find oil like his neighbor, John G. Gaillard, had on his property at nearby Goose Creek in 1903. The Goose Creek discovery brought a refinery owned by Humble Oil, and that refinery eventually brought workers and their families, a post office, a railroad, a school, and a new name for the place: Baytown.

As the refinery increasingly industrialized the city of Baytown, next door, the Brown peninsula remained what people in Baytown might have called “pristine”: undeveloped, remote, with miles of shoreline right on the waterfront and an unobstructed view of the bay. When Brown, Sr., died, his widow and their three children subdivided the peninsula, calling it “the Brownwood subdivision of Wooster,” selling lots on the Crystal Bay side to Humble Oil executives who sought to live in surroundings that reflected their station.

Early residents of the Brownwood subdivision described it as a beautiful place to live and raise a family: a peaceful setting by the water, where it felt safe to let children ride bicycles, to swim and fish, to paddle small boats out into the bay, to chase ducks or geese, or to lay back on the lawn and just count the trees. Parents could leave children unsupervised because everyone knew who lived there and who didn’t belong. Residents could stand in their living rooms, with giant walls of glass overlooking in-ground swimming pools, and watch rain blow in across the bay. They could watch barges and tankers while reclining on their lawn chairs and wave.

There aren’t many images of that former place, not that I’ve seen anyway. The ones I’ve come across mostly show what came after: photographs of flooded homes, footage of blown-out houses, only very occasionally a glimpse of the neighborhood in what residents might have considered its heyday—but nothing that captures what it was like before that.

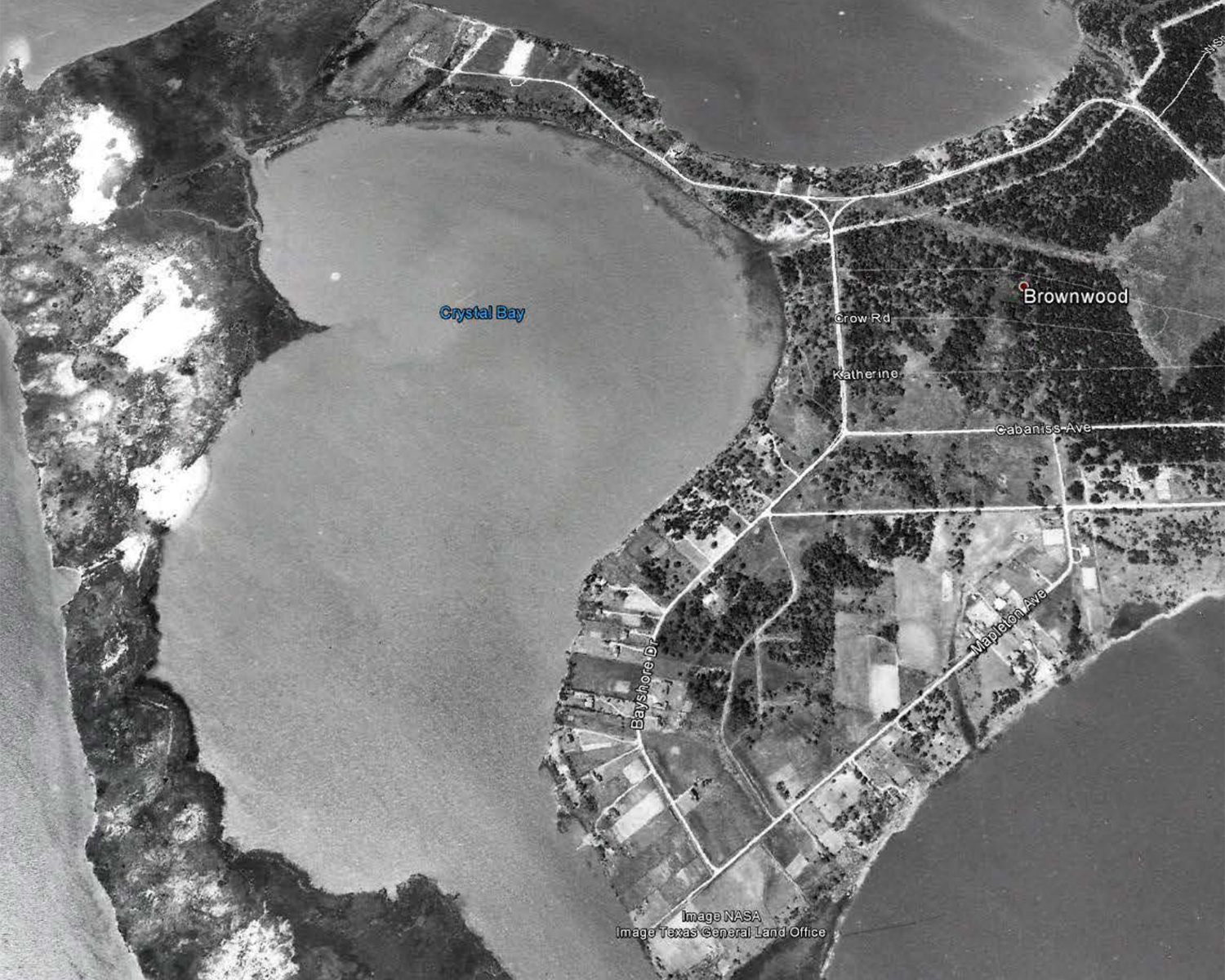

A NASA satellite image from 1944 shows a handful of homes along the southern edge of the peninsula, along Crystal Bay in particular, and the clear evidence of residents compelling the land toward separate purposes: the lines of pastures becoming mowed lawns and tilled gardens, the long driveways leading to homes on one-acre lots that graze the shore.

Just outside the frame of this image, on the mainland in Baytown, the Humble Oil refinery was drawing vast amounts of water to cool the crude oil they were pumping and heating, and they drew that water from wells supplied by the Chicot and Evangeline aquifers—part of a vast aquifer system that extends from Texas to Florida all along the margin of the Gulf Coastal Plain. Here, as elsewhere along the coast, the land is made of alternating layers of sand, water, and a soft compressible clay; as oil workers extracted the water, they removed part of the earth’s essential structure, and without that structure to hold it in place, the land began to subside at an alarming rate.

A second satellite image from 1953 shows the pace and nature of change: more homes, more roads, the land divided into smaller and smaller parcels. The second, outer peninsula is thinner, more like a series of knuckles than an entire hooked finger. Trees that appeared in backyards in the 1944 image are now submerged. Baywater approaches the homes, laps right at the back doors.

The subsidence didn’t come as a surprise to everyone, certainly not to the executives, to whom it was evident almost from the very beginning. “We drilled so many wells and took out so much oil that the land, which stood four feet above the water, sank to two feet under water,” Ross Sterling, founder of Humble Oil (and thirty-first governor of Texas), admitted in his memoir. Near the peninsula, at the Goose Creek oil field, the land subsided so much that workers had to build elevated roadways between the oil derricks and the mainland. Brackish water submerged vegetation as workers raised the derrick floors again and again. Before long, the whole oil field slipped under the surface of the water and disappeared.

During the years when war spread across Europe—as airplanes needed high-octane aviation gasoline (made from the condensed vapor of heated crude oil), as the military needed toluene for explosives (2,4,6-trinitrotoluene is also known as TNT), as troops needed butyl and butadiene for rubber—petrochemical facilities like the one in Baytown spread all across these bays and towns filled with the people who worked them: Clinton, Channelview, Pasadena, Deer Park. Highways unfurled across the continent as developers built new houses with attached garages on the peninsula.

Day after day, year after year, the refineries drew on the oil fields and on the groundwater in the aquifers beneath them. Over decades the whole region subsided—an area over 3,200 square miles—sinking everywhere at least a foot and in some places as much as ten feet. The most drastic changes were right near here, where the Buffalo Bayou and the San Jacinto River meet, where subsidence sunk entire ecosystems: woodlands turned to wetlands, wetlands to marshes, and thousands of acres entirely disappeared, leaving only open water in its place.

Brownwood, 1944

Brownwood, 1953

Brownwood, 1978

NASA / Texas General Land Office

Here on the peninsula, the subsidence became undeniable on September 11, 1961, when Hurricane Carla made landfall roughly 120 miles to the southwest, near Port O’Connor, Texas. The storm flattened homes and businesses, spawning nearly two dozen tornadoes all along the coast; when it arrived in Brownwood, an eleven-foot storm surge flooded homes all across the subdivision, many to a depth of four feet. Archival footage taken after the storm shows houses blown to pieces, furniture and debris strung all over yards, cars crushed and toppled on their sides. Residents later recalled taking refuge in their attics during the storm and eventually being forced out of their flooded homes by the military. When they were allowed to return by boat, they found loose pigs running wild and toucans taking shelter in the yards. They found their homes destroyed, found neighbors mourning the loss of everything they owned.

Humble Oil offered a few of its employees assistance following that storm, though many residents insisted they wanted to let their houses dry out a bit before deciding on their next move. Those who stayed rebuilt their homes. A number of them proposed that the Army Corps of Engineers build a thirty-foot-high levee to deter flooding; the city of Baytown responded by instead raising one of the main roads five feet.

In 1967, six years after Hurricane Carla, Hurricane Beulah flooded the peninsula again. Two years after that, in 1969, an unexpected storm on Valentine’s Day caused a high tide that flooded about 80 percent of the homes. The next year, in 1970, rain and rising tides flooded the neighborhood again; a year after that, the subdivision flooded with Hurricane Fern. Each time, floodwater came ashore and subsidence made it harder for it to recede. Each time, residents weighed the same decision: should we keep rebuilding, or should we cut our losses and leave?

By this time, the peninsula had subsided nine feet, going from eleven feet above sea level to two. Businesses had sprung up inside the subdivision: a beauty shop, a print shop, a plant nursery. Many of the original residents had sold or rented their homes to teachers, firefighters, barbers, mechanics. When Tropical Storm Delia hit the Texas coast in 1973, the storm sent water over the bulkheads and into the neighborhood.

In one photo of the damage, a national guardsman wades through chest-high water to approach a flooded home; in another, two men row through the subdivision in a boat. One photo shows a couple sitting in lawn chairs on dry ground in front of a house that is submerged behind them in water at least two feet deep. He holds a canned beverage in one hand—a beer maybe—and holds a cigarette in the other. She looks into the camera: one hand in her lap, the other resting on the arm of her lawn chair while they wait for the water to drain.

The same year Delia struck the Brownwood subdivision, Humble Oil merged with its partner company, Standard Oil. Beginning on January 1, 1973, the two companies would share petroleum products and a name: Exxon Company, USA.

Just enough of the past survives to show us a place that is no longer here.

The death of the Brownwood subdivision came in August 1983, when Alicia made landfall just southwest of Galveston as a Category 3 hurricane, putting the peninsula in the path of 100-mph winds and on the “dirty side” of the storm. A ten-and-a-half-foot storm surge rolled over the neighborhood, knocking homes off their foundations, tossing a telephone pole into the upstairs bedrooms of one home. One resident reported returning to find one entire wall of her kitchen completely missing—cabinets and counters and even the sink. She did find the silverware and plates, though, and even her clothes, which had all been sucked into the mud underneath.

Two weeks after the storm, the Baytown City Council voted to permanently close the subdivision, but residents fought to return. Eventually, the city shut down services to the peninsula: no trash pickup, no water, no electricity. FEMA offered residents a buyout; about a third of residents refused it, suggesting that the federal buyout didn’t reflect the full value of their property. Several moved back into their homes, hauling their own water and using generators for electricity. In a black-and-white photo taken in November of that year, one woman stands in her living room, flood debris scattered all over the floor, holding her hand to the wall to demonstrate the high-water mark above the mantlepiece. She is in her mid-twenties maybe, wearing a v-neck T-shirt with an image of Garfield screen-printed above the words “THIS IS ONLY TEMPORARY.” She didn’t want to leave, she told one reporter for The New York Times. “This is my home,” she said. “I bought it and paid for it. It’s the American dream.”

For a decade, houses collapsed and decayed. People used the yards and streets as a dumping ground. It continued that way until 1994, when the federal government ordered the principal polluting parties responsible for a nearby superfund site to restore a wetland area as reparation for their environmental crimes. After an extensive survey of possible sites, they chose this peninsula and over years this place began to change. Engineers bulldozed the few structures left standing and buried the rubble in trenches next to the foundations. They created freshwater ponds and dug three sixty-foot-wide channels to supply marshes with water; they established wooded areas on the new islands and brought in native plants. Over the years, other companies who have been ordered to mitigate their environmental harms have created additional marshes, installed a pavilion and a pier. Now, there is even a butterfly garden.

Today, at the nature center, we bike around the peninsula’s perimeter, past the stagnant lagoons with skins of green algae, past native marsh grasses and the mounds of invasive bramble. The trails are mostly gravel, though we bump over a crumbling patch of pavement as we turn from what used to be Bayshore Drive onto what used to be Mapleton Avenue. On a concrete bridge that spans the shallow channel, we find a pinfish flopping and gulping for air. I jump off my bike, catch the fish in my hands, toss it back into the water. It bobs to the surface, then jerks back to life and swims away.

Past the bend in the channel, on the mainland on the other side of the bay, towers flare at the Exxon refinery in Baytown. I remember a report a few years ago, known as the Carbon Majors report, that pinpointed the one hundred companies responsible for 70 percent of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions since 1988. Exxon was listed among the top five contributors and alone emitted at least 2 percent of total excess carbon over the past thirty-five years.

Around that time, I learned that Exxon scientists (then working for Humble Oil) had issued a report as early as 1957 that acknowledged “the enormous quantity of carbon dioxide” concentrating in the atmosphere “from the combustion of fossil fuels.” A little over a decade later, in 1968, an American Petroleum Institute study warned that burning fossil fuels would bring “significant temperature changes” by the year 2000, and that these temperature changes could be significant enough to result in “serious world-wide environmental changes.”

A month after the release of the Carbon Majors Report in 2017, Hurricane Harvey flooded hundreds of thousands of homes in the Houston metro region—many homes in my neighborhood among them. Two years later, Tropical Storm Imelda arrived without warning or emergency alerts while my husband was dropping our kids off at school and I was driving to the airport to catch a flight for work. By noon, the airport was surrounded by a moat and my husband was driving through flooded streets trying to bring our children home. I talked on the phone to my teenager as water pooled over the hood of the car. They told me their worst fear was of a moment like this, the water coming over the car and inside; of drowning in it.

After each storm, we try, as quickly as possible, to get back to what we have come to consider “normal.” The children go back to school. We buy a generator. We begin keeping a week’s supply of bottled drinking water in the house. We insulate the attic and stock up on nonperishable goods.

After the Freeze, we drove to the nature center and let the children climb out onto the rubble at the end of the peninsula at low tide. I sat under a pavilion on the shore, noticing the towers flaring at a refinery in the distance, how the concrete under me had holes for drainpipes, how stairs led to a threshold that no longer existed; realizing that the place I stood had once been the foundation of a home. Off to one corner, I found a bathroom-sized patch of pink floor tile.

Today, I pass that pavilion again and continue down the trail, past a concrete foundation with peeling linoleum tile. I find one foundation buckled and cracked into dozens of pieces. We bike through a thicket and are swarmed by mosquitos. Along the peninsula’s northern edge, we see dozens of homes along the mainland shore, perched above manicured lawns on tall stilts. People live there still. Towers carry powerlines to the refineries across the bay.

Looking at those refineries—all that steel and smoke and fire, the endless infrastructure of it all—I feel small, overwhelmed, even a little powerless. And maybe that’s the point: to convince us that the fossil fuel industry is stronger than we are, more permanent, irreversible even. As if our only choice is whether to keep repairing the damage after every disastrous storm. Here, on this peninsula, residents built bulkheads behind their homes to try to keep the flooding out, and then rebuilt their homes after the flooding destroyed them anyway. How is what I do after every disaster not the same?

It’s normal to want to repair what’s broken, folly to repair what breaks us and keeps on breaking. The destruction of the neighborhood on this peninsula—and the attention to the problem of subsidence it generated—led to limitations on the withdrawal of groundwater from area aquifers. Over time, refineries and area municipalities began to convert from ground water sources to surface water sources, but not completely. Subsidence remains a threat, but it isn’t by any means our only or even our most urgent one. Increasingly, we face those “serious world-wide environmental changes” scientists warned about more than fifty years ago: sea level rise, floods, erosion, more and stronger hurricanes, more and stronger floods, winter storms that plunge millions into freezing darkness for days, and threaten blackout for months—pollution, fires, droughts, extinctions.

What strikes me here today, more than it did before, is that sometimes we try to protect the places we love and end up losing them anyway: a neighborhood, a peninsula, a marsh upriver, a riverine woodland. We need space and time and ritual to grieve these losses, but we also have to love whatever emerges in their place. This place—where herons pick through marsh grass looking for crawfish and mounds of bramble swallow swimming pools and fire hydrants—is just as precious and vulnerable to destruction as the places that were here before. We live in what Gramsci called “a time of monsters,” when the “the old world is dying, and the new world struggles to be born.”

We stop in a grove of giant palm trees along the waterfront, named after the man who planted them in what was then his front yard. We park our bikes and walk to the end of the pier. A brown pelican floats on the same wind that blows goldenrod and milkweed back on the shore. Out beyond the edge of all that is no longer there, I can almost see the ghost of this moment in the future, and feel that haunted future, looking back.