George Prochnik is the author of In Pursuit of Silence: Listening for Meaning in a World of Noise and The Impossible Exile: Stefan Zweig at the End of the World, which received the National Jewish Book Award for Biography in 2014 and was shortlisted for the Wingate Prize. Prochnik is editor-at-large for Cabinet magazine and has written for The New Yorker, The New York Times, Bookforum, and The Los Angeles Review of Books. His latest book Heinrich Heine: Writing the Revolution is forthcoming from Yale University Press.

Studio Airport, founded by Bram Broerse and Maurits Wouters, is an interdisciplinary design studio that ventures out into the cultural ether to forage for anomalies, creating work that spans art, culture, science, and ecology. In addition to Emergence Magazine, their creative partners include the Design Museum, See All This Art Magazine, Slowness, Normal Phenomena of Life, and Sapiens Magazine. They serve as master tutors at the Design Academy Eindhoven and were recognized as European Agency of the Year 2024 by the EDA.

In an age when the fate of the world is frightfully unknown, George Prochnik makes a case for uncertainty as a form of faith and hope.

1

We long for certainty. Society ingrains the wish, and our fear of its not being answered can feed upon itself until the ground beneath our feet dissolves. Religious faith rushes in to fill that yearning, like water descending a sheer incline, until all emptiness is gone and some final equilibrium is reached. Insecurity plays the role of gravity in the realm of spirituality, drawing us toward belief, the promise of a haven where that force no longer operates: free fall replaced by an encompassing embrace.

In the absence of that certainty, where are we? The questions keep proliferating once they start. What will happen to us when we can no longer live where we are now? Perhaps we had no real place here to begin with, or if we once did then something’s changed. What will we do next? And what will happen when that next respite ends? We’re becoming less and less sure about the prospect of employment. Our bank accounts are dwindling. And the disease we might or might not have? And the unfinished work on which we staked so much? And the possibility of war? And the eyes of that poor stranger? And the rising, ever rising seas, and fires and flames and burning rage? Good Lord, all the suffering beyond our own horizons—how will that ever be assuaged? What will happen to the children, the parents, their lost friends, the millions suffering at this moment in ways that overwhelm our powers of imagining?

How can we get out of bed in the morning given everything we’re supposed to do and can’t find energy or focus even to begin? What happens if we do wrench out of bed precisely when we’re supposed to and find ourselves sitting down once more staring dully at our coolly glowing screens, like at the inside of a refrigerator that contains nothing which can actually be eaten—a refrigerator we know will never be stocked simply by staring at the vacancy, and yet we can’t bear to tear our eyes away from it because then even the illusion of fullness won’t be there, and we’ll have to gaze once more into a vortex of unmanageable demands, until the two states conflate: All the obligations we don’t know how to meet, and the empty tracts of time we don’t know how to fill. Lovers. Lovers we don’t have. Enemies, bosses, and the people from the bank—along with our wrath-engorged Contaminator-in-Chief, and the greater globe in which each problem we reflect on seems bigger than the one that came before, until finally we come back around to our own tiny plot and find we have no idea what to do about anything, let alone the everything we’re somehow meant to face.

Give us God in whatever form She, He, It, or They consents to assume, so long as that transcendent something supplies us with an answer we can curl up around close enough to breathe ourselves to peace, or anyway to sleep.

Lord give us this night our daily certainty.

Say it. Say it. Now repeat.

2

But suppose we’ve got it wrong. Say we missed a turning in the maze. Or that at the least, there’s another way of approaching our predicament that has the potential to reframe our fate. Suppose our reflexive sense of dependency on certainty is itself a form of faith: the belief that we require certainty serving as the left half of an equation that concludes, after the equal sign, with religion supplying that certitude. Perhaps, in fact, one of the psycho-spiritual traps of the moment is an overwhelming conviction that we do know how everything is going to turn out—badly, as it happens. Very.

In this scenario, the type of comfort we seek from religion might involve the opposite of a stereotypical certainty regarding who we are and what comes next. (We get that in plenty already from our self-affirming, spirit-desiccating feeds.)

There is a different, more subterranean tradition of theological solace predicated on restoring—not optimism, but a sense of the unknown. The first step toward creating some way out of our dilemma may involve allowing our sense of certainty itself to unravel. This doesn’t mean succumbing to a fatuous denial of dire present-day realities, but rather restoring a sense of amplitude to all the time we’ve not yet lived through.

What might it mean in practice, though, for a religion to offer fertile uncertainty? How do we chart the borders of an unknown state as the sanctuary of possibility without dissolving reality altogether in a stew of soft-edged platitudes? Especially since mystery and obscurity have traditionally been wielded by religious authorities in a manner aimed at augmenting inscrutable power—underscoring the flock’s dependency on those who claim to hold the only keys to the dark treasures of eternity.

3

We might start searching in the East.

A famous story circulates among disciples of Taoism involving a hunting party of a hundred thousand men led by Prince Chao Hsiang Tzu into the Central Mountains. In order to drive the trophy animals into the range of their weapons, the prince’s attendants scattered sparks through the underbrush; but they were too zealous in preparing for their sport, and soon the entire forest was ablaze. The flames were visible for a hundred miles. It was obvious that nothing on the mountain could survive the catastrophe.

Suddenly, a man appeared, stepping out from the face of a rocky cliff. He hovered in the air, between the fire and the smoke. All the gathered hunters assumed he must be a disembodied spirit.

When the conflagration had finally swept on, the man descended and walked silently away from the devastation. Hsiang Tzu was full of wonder and insisted that the man be detained so he could be examined. The physicians who’d been called in to study him declared that he was unquestionably a living human being, in possession of all seven channels of sense—breathing and speaking as only a person of flesh and blood could do.

The first step toward creating some way out of our dilemma may involve allowing our sense of certainty itself to unravel.

So the prince asked him what secret knowledge he possessed that allowed him to exist inside rock and to walk through fire.

“What do you mean by rock?” the man responded. “What do you mean by fire?”

Hsiang Tzu answered: “What you emerged from just now is rock; what you just now stepped through is fire.”

“I know nothing of them,” replied the man.

The legend is interpreted in different ways, most involve the notion of the man having attained a state of unconsciousness so intense that the dangers engulfing him could not affect his corporeal being. This extraordinary individual had thought himself into a place beyond concrete reality, within the nimbus of an immunizing absence of worldly knowledge.

But doesn’t this gloss suggest that salvation lies merely in obliviousness? A bit like saying, what you don’t know can’t burn or crush you?

Another way of approaching the story would be to propose that the figure stepping from the cliff face is a fantasy of the prince and the hunters, inspired by their need to alleviate the guilty knowledge of having negligently provoked disaster—“Behold, were there a person of sufficient spirituality, he would survive whatever damage we inflicted!”

However, the fantasy ultimately foils the men’s wish to avoid responsibility. For the type of unconsciousness that could transcend reliance on, or susceptibility to, the senses is antithetical to the state of mind in which one might thoughtlessly torch a mountainside to gratify the bloodthirsty appetites of a hundred thousand hunters.

In this interpretation, un-learning knowledge about the fire’s ineluctable trail of destruction becomes the path to imagining another form of awareness that calls into question the entire way of life in which such blithe consumption of resources would be permissible. What steps out of the fire before the prince is an image of not knowing that ultimately casts the self as hunter, and earthly power as such, into doubt.

What do you mean by rock? What do you mean by fire? And what does society mean by prey, or prince?

How do we ourselves cultivate a species of imagination that enables us to think beyond the rock and fire of the present hour?

4

We might turn westward for clues as well.

Hadewijch, a female mystic and poet, lived in the Low Countries in the thirteenth century. She appears to have served as the head of a Christian lay order in the Duchy of Brabant, a position which probably involved ministering to the ill, or teaching the young—or both together—though nothing is known for certain about her life beyond the fact that she had visions, which she wrote about in letters, and verse that she composed in the vernacular. We can also assume that she developed her challenging perspective on faith outside the circle of religious authorities, since this was the domain of men.

Perhaps her status at the margins makes her disregard—or even antipathy—for traditional categories of knowledge less surprising. Thus, for instance, in a letter on the role of reason in human affairs, she asks her correspondent to consider the areas in which reason errs, and enjoins the recipient to reform in these matters with all the ardor he or she can muster. “To put it briefly,” Hadewijch writes, “reason errs in fear, in hope, in charity, in a rule of life one wishes to keep, in tears, in the desire of devotion, in the bent for sweetness, in terror of God’s threats, in distinction between beings, in receiving, in giving—and in many things we judge good.”

Otherwise, reason is just fine.

Glimmers of a compassionate social consciousness flicker through Hadewijch’s questioning of reason’s grasp on the world. The kinds of distinctions—and failures to draw distinctions—that she criticizes almost invariably involve some proprietary arrogation of the world’s blessings to one’s own self alone. “In possession of any sort … reason errs,” she avows. At heart, such mistakes derive from compromising what Hadewijch defines as the liberty of perfect love. The idea of liberty she invokes seems aligned with the state of nonjudgmental receptivity advocated by certain schools of Buddhism. But Hadewijch wants her readers to exercise their passions while opening themselves to everything, and to come away from this experience marveling at the world—rapt in ecstasy.

As the scholar Amy Hollywood has observed, through all of Hadewijch’s richly miscellaneous teachings and self-educating lines of inquiry, the leitmotif is love. Often this preoccupation takes the form of an exploration into what love means at the most fundamental level, a probing that goes beyond any strictly theological interpretation to become a meditation on the boundaries of knowledge as such. In one of her final visions, Hadewijch depicts the soul encountering an allegorical figure of wisdom in the guise of a queen dressed in a golden gown sequined with myriad transparent eyes that resemble flames and crystals. In rapture at this sight, she becomes aware of “God alone as God, and all things as God in God’s knowledge, and each thing as godlike.” With her sense of earthly knowledge bedazzled, Hadewijch loses her awareness of the hierarchy of Creation. Everything around her undergoes an apotheosis. This is a kind of not-knowing that rises beyond the category of knowledge to a quasi-pantheistic democracy of the deified. The queen of wisdom draped in golden folds of flashing eyes falls in stature after this revelation to become Hadewijch’s subject. In time, Hadewijch leaves the figure entirely behind her. At that point, “love came and embraced me,” Hadewijch writes, “and I came out of the spirit and remained lying until late in the day, inebriated with unspeakable wonders.”

But what, we might ask, does the kind of wonder induced by the surrender of wisdom in the name of love enable? If we can imagine ourselves in the state of intoxication in which Hadewijch describes herself reposing until day’s end, what happens when she rises the next morning? If she returns to the humble ministrations of her work for the religious order, are these elementary tasks of caring for others then imbued with the character of her unknowing awe? Was she able to communicate to those in her charge the feeling of a sudden opening—a glimpse into hitherto unknown sublime possibilities—that wonder can bestow?

A Turkish proverb offers the inverse form of Hadewijch’s euphoric self-abnegation: Whoever, other than God, says I is a demon, since all things derive from God and God alone is self-existent. The negative “I” claims to be all-knowing, to embody complete autonomy, autarchy—self-entitlement and infinite solipsism: megalomania. The opposite of laying oneself open to the world in a state of loving un-knowing is to be so consumed by one’s own greatness that the world outside exists only as another bloody morsel for one’s own consumption.

5

In the nineteenth century, certain German thinkers operating at the border of science and the fantastical borrowed a term from astronomy to characterize the object of their speculations. Just as contemporary astronomers described the face of a planet turned away from the sun as its “night side,” these investigators found a parallel between the dim perceptions we can achieve of a planet’s night side and the obscure perception we glean of those parts of nature where the occurrences we designate as wonders have their wellspring. It’s a commonplace that familiarity blunts our awareness of everyday reality. Just so, unfamiliarity can remap our sense of the world. So, for instance, at night the silhouetted peaks of a mountain chain might be visible even though it would not be possible to make out the undulating hills that fuse the landmasses underlying the crests. The image of the independent peaks has no geological validity, but conjures its own unique chain of associations in the observer, which can reconfigure their understanding of the space before them.

The urge of spiritualists and other enthusiasts of psychic phenomena has traditionally been to cast an artificial—often purposefully distorting—blade of light into this mysterious realm. But what if the nocturnal side of nature is thought of less as the source of an alternative variety of knowledge than as a catalyst to the imagination, a preserve of images that have no known purpose, yet which compellingly reveal how the possibilities of the world have not yet been exhausted? At certain moments, alone or with a loved one, switching off the light in a room becomes a way of making the space larger, even boundary-less.

In this vein it’s worth considering that were we ever able to receive a communication from “the other side,” or the “next world,” there’s no message that could be delivered which would be more momentous than the notion that such a realm exists at all. This is the case not only because that communication would reconfigure our sense of the depths of the world we inhabit now, but because the validation of our dream life thereby conferred would carry untapped implications for how we conduct ourselves toward the future.

To consider this idea from another angle, we might step outside the realm of overt spirituality into the border field of aesthetics. There’s a historical anecdote that illustrates how the act of cultivating funds of imaginative aptitude can work against the oppressive consciousness of defeat in such a way as to enable an entire city to recreate itself in the wake of catastrophe.

In 1940, two years after Adolph Hitler annexed Austria to Germany and just months before the fall of France, the Viennese writer Stefan Zweig delivered a lecture in Paris titled “The Vienna of Yesterday.” The speech is laced throughout with poignant observations about the city’s cosmopolitan and ethnically and religiously diverse heritage. But perhaps its most original passage comprises a fervent defense of the arts as a seedbed for ideas and skills that might one day rescue civilization—even though they should be practiced with no knowledge of or concern for potential real-world applications.

Zweig writes of Vienna’s long, distinguished history of devotion to the arts, music, and theater in particular. He describes the almost fanatical dedication of Austrian performers and composers to their trade—as well as the intensely passionate attention of Viennese audiences to these virtuoso exhibitions. How the Germans used to ridicule the Austrians for their frivolous pastimes! Zweig exclaims. The Austrians were considered pathetically ignorant about how to be productive, just as they were viewed as useless when it came to understanding how to prevail on the battlefield or in business. They had, indeed, no meaningful quantifiable knowledge whatsoever. “For the German people,” Zweig wrote, “the concept of ‘jouissance’ is always linked to effort, activity, success, to victory. To be fully himself, each must outstrip his neighbour and if possible oppress him.” Instead of this philosophy, the Austrians had cultivated the idea that “one must be free and leave others to their freedom,” without being ashamed of “taking pleasure in existence,” finding and creating beauty—daydreaming about other worlds.

So far as the Germans were concerned, the Viennese lack of knowledge about the transactional, zero-sum workings of reality doomed the Austrian Empire to absolute irrelevancy.

And yet, Zweig declared, in truth, at the end of the First World War, when Vienna lay in ruins, with grass growing in its streets and all the roads leading to the provinces from where the capital drew its resources cut off—when the trains were without coal, and the shops were empty of bread, fruit, or meat, and the currency was becoming devalued by the hour—all that supposedly idle, feckless immersion in the pursuit of aesthetic joy proved to have another dimension, which the Viennese themselves had been unaware of until that time. For, Zweig argued, it was precisely all those countless hours spent practicing the arts and handicrafts that gave the city’s residents the skills and imagination necessary to resurrect a city that war and disease had virtually annihilated. “The miracle happened,” Zweig wrote: In three years everything had been rebuilt. In five years, the city had constructed blocks of communal houses that became the model of successful socialist governance for all of Europe. Commerce resumed. Galleries and gardens were restored. “Vienna became more beautiful than ever before,” and suddenly found itself at the forefront in a hundred vital areas.

In Zweig’s vision, the art of the imagination, to which the city had accorded primacy, gave the population faith that the apocalyptic scenes before them were as impermanent as stage sets. And the conviction that these sights could be transformed came in tandem with an understanding of how the transformation could be effected which went beyond what might be derived from any rigid manuals of pragmatic knowledge.

6

Beyond this point nothing may be known or understood, and therefore it is called Reshith, that is “Beginning,” the first word of creation.

— the Zohar

If in dark times certainty about the nature of reality can trigger despairing resignation, or an egoistic conviction of one’s right to manipulate the substance of the world for private gain, what form of hope emerges from a religious sensibility that dispenses with such confidence? For the final passage into this perspective, I want to tell a story within a story that centers on the Kabbalah. These nesting tales emerge through forms of knowledge, or not-knowing, that evolved along the border between East and West. They also each involve an individual caught in a personal crisis that echoes with larger, urgent questions of their respective eras, and perhaps our own.

In late-thirteenth-century Spain, an impoverished, itinerant rabbi, philosopher, and poet from Castile by the name of Moses de León had reached the end of his rope. He had a family to support and no synagogue would pay him enough to survive. In some desperate hour, de León began scribbling down a wild, visionary commentary on the Hebrew Testament and the core books of Jewish Law. In his work, the Torah was conceived of as a vast symbolic body that graphed God’s hidden life, the ten stages of His inner world, which were also the attributes through which God became manifest. Nothing in the Torah meant what it appeared to say on the surface, de León maintained. In fact, he argued that if the Torah were composed of only those stories, lineal chronicles and political viewpoints that could be comprehended literally, “we should be able even today to write a much better one.” However, in truth, limitless esoteric meanings could be divined by plunging deeper and deeper into the successive layers of this sacred text, which itself was ultimately nothing other than the Name of God.

There was no possibility of comprehending this Holy Name, only of adding new interpretations that themselves spawned yet further interpretations. The images de León created often seem to float in a kind of nocturnal aureole, casting around themselves a negative space in which, because of the obscurity of what’s being described, there’s room for readers to project their own dream-visions. “A dark flame sprang forth from the innermost recess of the mystery of the Infinite,” begins its second sentence. “En Sof [Without End], like a fog which forms out of the formless.…”

At some point, de León started bundling sections of his fragmentary narrative together and presenting them to his community as parts of a book he claimed had been composed by a second-century sage named Shimon Bar Yohai. The manuscript came into circulation piecemeal, over a number of years. All he was doing himself, de León explained to others, was transcribing the words of this hallowed master from antiquity. When his wife and daughters walked in on de León and saw him working at a bare table with no manuscripts beside him from which he might have been copying Bar Yohai’s words, they asked him why he was pretending that the book had been hatched anywhere but his own brain.

I’m only doing this to make some money, de León told them. No one would buy the book if they knew I wrote it.

The answer dismayed them.

But de León responded, basically, I’ve got no choice, and kept on writing.

In his lifetime the work, which became known as the Zohar—“Splendor”—never found an audience beyond the small circle of local Kabbalists among whom it circulated in handwritten manuscript. If de León really had intended it as a source of income, the scheme was an abject failure.

But if de León’s aspirations were more complex than, according to the tale, he revealed, then the Zohar’s “failure” had its own obverse, night side that would eventually spin toward the light.

I do not know what happens next becomes an iteration of hope instead of helplessness.

Some three hundred years after de León’s death, in Renaissance Italy, the work was printed for the first time. A group of influential Kabbalists came upon the manuscript and embraced the Zohar as if it had been a seed lying dormant through the centuries until they could discover it. Their passionate conviction of the Zohar’s profundity seemed to derive at heart from the book’s imaginative response to the anguish of human suffering that more traditional commentary couldn’t respond to except in crude formulae that made suffering out to be a consequence of sin.

From the time of its first printing in the sixteenth century up until today Jewish communities receptive to mysticism came to consider the Zohar something close to a Bible of Kabbalah—the fundamental repository of images and insights that populate the vast network of texts which together comprise the Jewish mystical canon.

Indeed, the extraordinary success of the work led rationalistic nineteenth-century scholars to condemn the Zohar as one of the most reprehensible forgeries in Jewish history—a manuscript that had deluded people for generations with the eccentric fantasies of an indigent fraud. Instead of providing some kind of enlightened solace for a community suffering multifold persecutions, the Zohar had thrust them deeper into darkness. It “confirmed and propagated a gloomy superstition, and strengthened in people’s minds the belief in the kingdom of Satan, in evil spirits and ghosts,” wrote Heinrich Graetz, one of the most eminent of these historians who sought to prove that Judaism was compatible with universally sanctioned precepts of ethical thought.

But in the first half of the twentieth century, the significance of the Zohar was reassessed once more by a new generation of Jewish historians, led by the Berlin-born humanist scholar, Gershom Scholem, one of Walter Benjamin’s closest friends. Scholem was concerned not with demonstrating Judaism’s reasonableness, but with the question of whether the Jewish people possessed the imaginative energy necessary to think beyond the catastrophe of contemporary European history. For, in Scholem’s estimation, his community faced a cataclysm of titanic proportions that reason alone could not surmount. In truth, it had begun long before Hitler’s ascendancy. Before the end of the First World War—before his own twenty-first birthday—Scholem had decided that insofar as Jews aspired to a vibrant purposeful existence, the Jewish people had no future in the Diaspora. Partly this was due to anti-Semitism, which assured that Jews would always be held in contempt by the European community, excluded from the ranks of fellowship and denied integral value. However, even more enraging to him than the way Germans had treated the Jews was how the Jews had responded to their classification as undesirable aliens. Instead of trying to transform the larger world, they’d sought to erase their distinctive identity by conforming to the bourgeois status quo.

In discovering the Kabbalah, Scholem felt he’d identified a neglected, explosive element in Jewish theology that could inspire new forms of real-world engagement for the people. As he wrote in one essay, “There is such a thing as a treasure hunt within tradition.” Even the process of embarking on this kind of search for unexplored dimensions of one’s heritage could create a reviving kind of self-awareness, Scholem believed, one that untethered the future from any predetermined destiny.

Striving to identify the integral character of Judaism, Scholem concentrated more and more on its boundless, protean quality. “Judaism cannot be defined according to its essence, since it has no essence,” he declared in one essay. Moreover, he added, if Judaism couldn’t be defined in any dogmatic way, one couldn’t presume that it “possesses any a priori qualities that are intrinsic to it or might emerge in it; indeed, as an enduring and evolving historic force, Judaism undergoes continuous transformations,” Scholem wrote, drawing on Kabbalistic principles.

These ideas reached a kind of pitch as Scholem sought to apply concepts from the Zohar to the historical predicament on the eve of the Second World War. In a lecture delivered in New York in 1938, five years after the Nazi’s racist, nationalist program had begun to be implemented throughout the Aryan Fatherland, Scholem declared that the spiritual outlook of the Zohar was a singular mixture of cosmogony, psychology, and anthropology. The work proposed that “God, the universe and the soul do not lead separate lives, each on its own plane,” but instead crisscrossed, intermingled, and informed each other on every level. This meant that humanity, in the process of attaining the deepest possible self-understanding, simultaneously acquired an intuition of God’s essence. The utmost expression of God’s personality became unexpectedly identified with that “which is nearest to human experience, indeed which is immanent and mysteriously present in every one of us.”

This did not mean that the destiny of humankind was secure, let alone that the Zohar’s adepts could deduce how everything would turn out. Rather than providing a form of consolation which assured believers they’d be taken care of by God the Father, the Zohar, in Scholem’s telling, offered solace by expanding the sense of self to the point of a vertiginous cosmic solidarity. Instead of supplying comforting knowledge, the Zohar conveyed a sense of magnitude—possibilities still unplumbed, latent in the dark flame that leapt from the innermost recesses of mysterious infinitude.

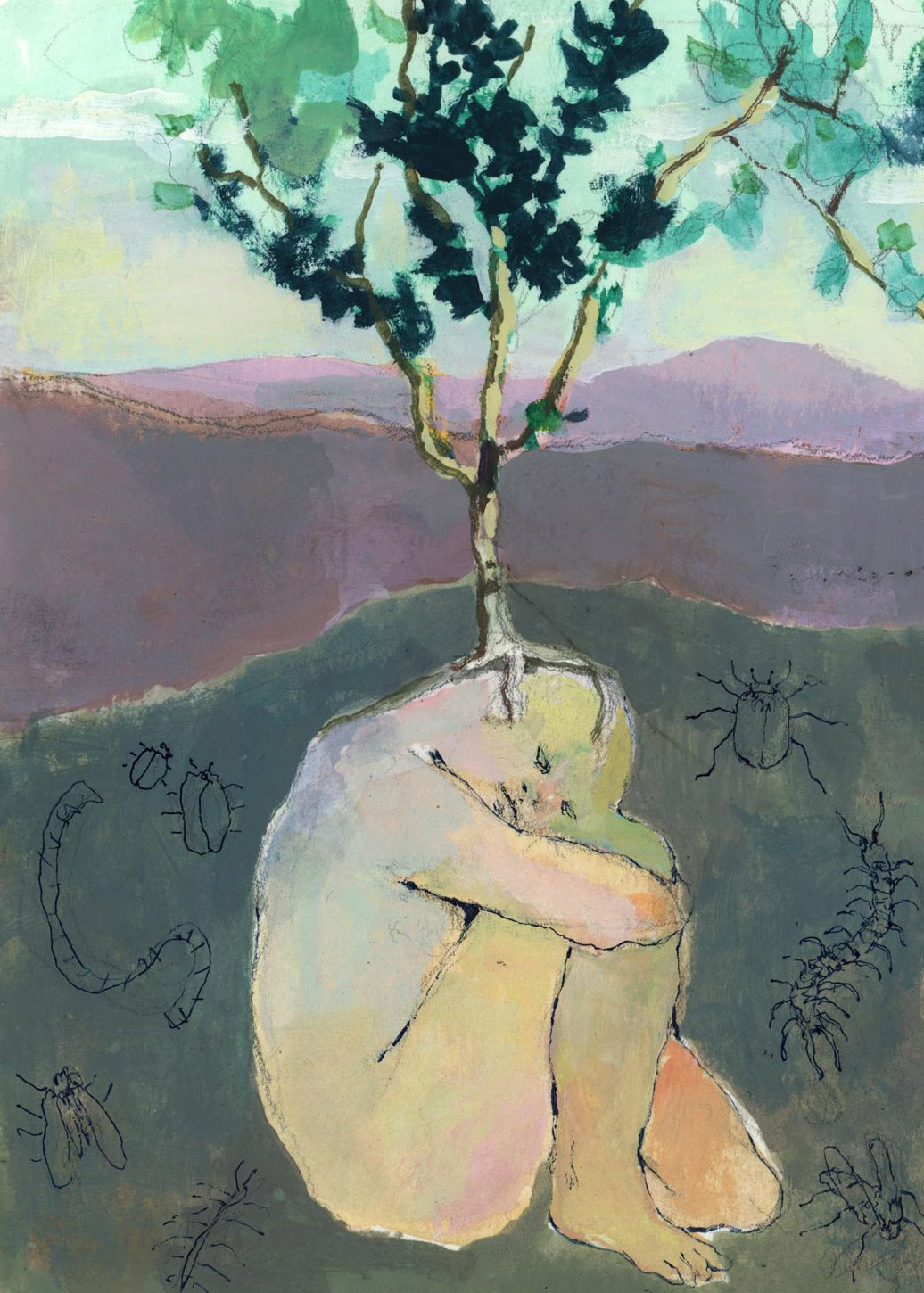

Evil, according to the Zohar, invariably entails “something which becomes separated and isolated, or something which enters into a relation for which it is not made,” Scholem writes. “Sin always destroys a union, and a destructive separation of this kind was also immanent in the Original Sin through which the fruit was separated from the tree, or as another Kabbalist puts it, the Tree of Life from the Tree of Knowledge. If man falls into such isolation—if he seeks to maintain his own self, instead of remaining in the original context of all things created, in which he, too, has his place—then this act of apostasy bears fruit in the demiurgical presumption of magic in which man seeks to take God’s place and to join what God has separated. Evil thus creates an unreal world of false contexts after having destroyed or deserted the real.”

From this vantage point, an overweening sense of security about our position here on earth can only be attained by divorcing ourselves from the rest of nature, denying our envelopment within the whole of Creation—promulgating a myth of self-made insularity, that is the Kabbalistic epitome of wickedness.

Moses de León and other leading Jewish mystics found a way to engage creatively with the devastating traumas of Jewish history, one that rewrote their significance for the community’s future. By creating a powerful symbolic language that resonated with the struggles of ordinary men and women, the Kabbalists gave meaning and purpose to the engulfing fear and despair of exile and persecution. Far from inducing fatalism, the long history of suffering transmitted an urgent vocation: Kabbalah intertwined the roles of God and man so that humanity was assigned a dynamic role in rectifying what had gone awry in reality. Through prayer, ritual, and a home life conducted with profound ethical attention, people now became instrumental in helping God “fix” creation.

Gershom Scholem recognized the enormous danger of the times in which he lived, but felt that with the peril of periods of intense destabilization came a uniquely charged potential for change. He coined a term for the eras involving vast migrations of peoples, conflict, and radical political reorientation, calling these interludes the “plastic hours” of history: “Crucial moments when it is possible to act. If you move then, something happens.”

He interpreted de León’s appropriation of the name of an earlier sage not as a venal act of forgery, but as an effort to imaginatively seize hold of fate and project himself beyond the misery of his immediate circumstances. “The psychological stimulus emanates from modesty and the feeling that a Kabbalist who had been vouchsafed the gift of inspiration should shun ostentation,” Scholem wrote. “The further a man progresses along his own road in this Quest for Truth, the more he might become convinced that his own road must have already been trodden by others, ages before him.”

At our moments of most intent receptivity, we no longer know the source of the voice that leaves our own lips—only that it is part of a greater collective lineage of truth seeking. Not knowing exactly what speaks through us, other fatalistic certainties blur as well. The consciousness of our historical doom takes on something of the plasticity Scholem invokes—perhaps enabling us to say something unexpected: I do not know what happens next becomes an iteration of hope instead of helplessness.

What is rock? What is fire? What is darkness? What is government? What is country? What is freedom? What is love? What is resistance? What is righteousness?

Keep asking the questions, until the context deepens and evil is transformed beyond recognition. In Zoharic terms, “that is ‘Beginning,’ the first word of creation.”