Jeffrey Jerome Cohen is Dean of Humanities at Arizona State University. He is widely published in the fields of medieval studies, monster theory, and the environmental humanities. His book Stone: An Ecology of the Inhuman received the 2017 René Wellek Prize in comparative literature from the American Comparative Literature Association. In collaboration with Lindy Elkins-Tanton he co-wrote the book Earth, a re-examination of our planet from the perspectives of a planetary scientist and a literary humanist. He is the co-author, with Julian Yates, of the book Noah’s Arkive: Towards an Ecology of Refuge.

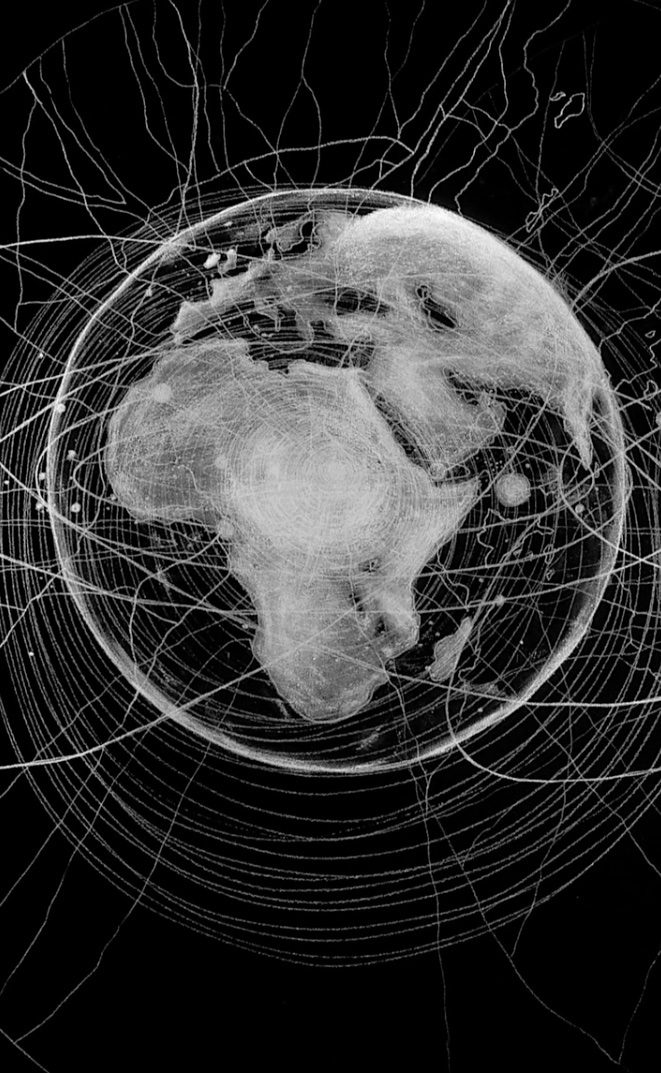

For thousands of years, humans have imagined what it would mean to view the Earth from celestial heights, raising the question of how to reconcile our bounded lives with our longing for the cosmos.

Sometimes even writers who dwell too much on earthbound things feel a celestial pull, an invitation to a loftier perspective. The irascible medieval writer Gerald of Wales, for example, spent much of his life being disappointed by people and institutions. In numerous texts he composed in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, Gerald vented his anger at various groups to which he did not and could not belong. He is famous for describing ways to conquer lands whose residents would rather have been left alone. He felt an early calling for the study of divinity. As a child Gerald built cathedrals rather than castles out of sand. Earthly life was for him unquestionably the gift of a deity active in a world that he had fashioned and loves. After he became a cleric, though, Gerald wrote frequently about the tribulations of travel, the barbarity of foreigners, and the petty rivalries of the English court. And yet he also at times felt a kind of magnetism from the heavens, an invitation to regard the world from a more elevated point of view where the travails that weigh down everyday life might yield to a more capacious vista, disorienting in a productive way.

Like most medieval writers, Gerald of Wales believed cosmic as well as divine forces to be at work above. He knew that our eyes are never content simply to search the ground beneath our feet or scan oceanic horizons. Humans look skyward because something in the heavens draws their vision and asks them to lift their heads, causing them to wonder what it would be like to be up there gazing down. Would the order of the world be revealed? In contemplating what energies animate this turbulent Earth, Gerald recognized the tug that the firmament exerts, an irresistible attraction pulling all things skyward. As the light of the moon waxes, he wrote in his Topography of Ireland, the oceans swell and surge. The same cosmic force ensures that the sap of trees rises. Marrow and the vital fluids of every creature begin to lift, drawn toward a destination never to be reached but beckoning all the same. We feel this celestial allure in our very blood. For a medieval Christian, that pull might be the call of a place to be reached only after death. But the fact that our bodies remain earthbound never stopped writers across the ages from imagining what it would be like to yield to this extraterrestrial gravity, visit the sky, and behold a home now left behind as if from afar.

I am writing these lines in what the pilot describes as “moderate turbulence” in an airplane cruising at thirty-five thousand feet. According to the map displayed in a panel on the seat in front of me, directly below this plane is an island called Nuku’alofa, a dot on the tectonic ridge just before the Pacific Ocean plunges to its deepest valleys. I cannot see the island because of the storm that is causing my seat to tremble and my laptop to shake. I am wondering here amongst the clouds what Gerald would have made of such modes of travel and the perspectives they afford. Mostly he journeyed by foot, horse, or ship, modes of transport that ensure you are always in the thick of things: too hot, cold, or wet, the plaything of the elements. Seated in a Boeing 787 that voyages every day the long route from Melbourne to Los Angeles, I am wondering about Gerald of Wales. In describing the pull of the Moon, didn’t he also describe how the heavens beckon us toward the stormy atmosphere and beyond: to the Moon, to Mars, to the edge of everything we know? Didn’t he identify centuries ago the enduring urge to take to the sky and behold the Earth from above? Gerald realized that some abiding force stirs us to look back upon the only home we have ever known as if we could depart. He surely did not dream of machines that could accomplish such feats, technology that would enable us to respond by rising above cities, mountains, oceans, and islands and hope to see them from above. But that did not mean that he wrote at a time that could not imagine a perspective that frames the Earth from its outside: above, looking down, human bustle rendered invisible, home become a dot.

We are pulled upward by the sky, an irresistible counterforce to our attachment to the only habitation we know.

We feel this celestial allure in our very blood.

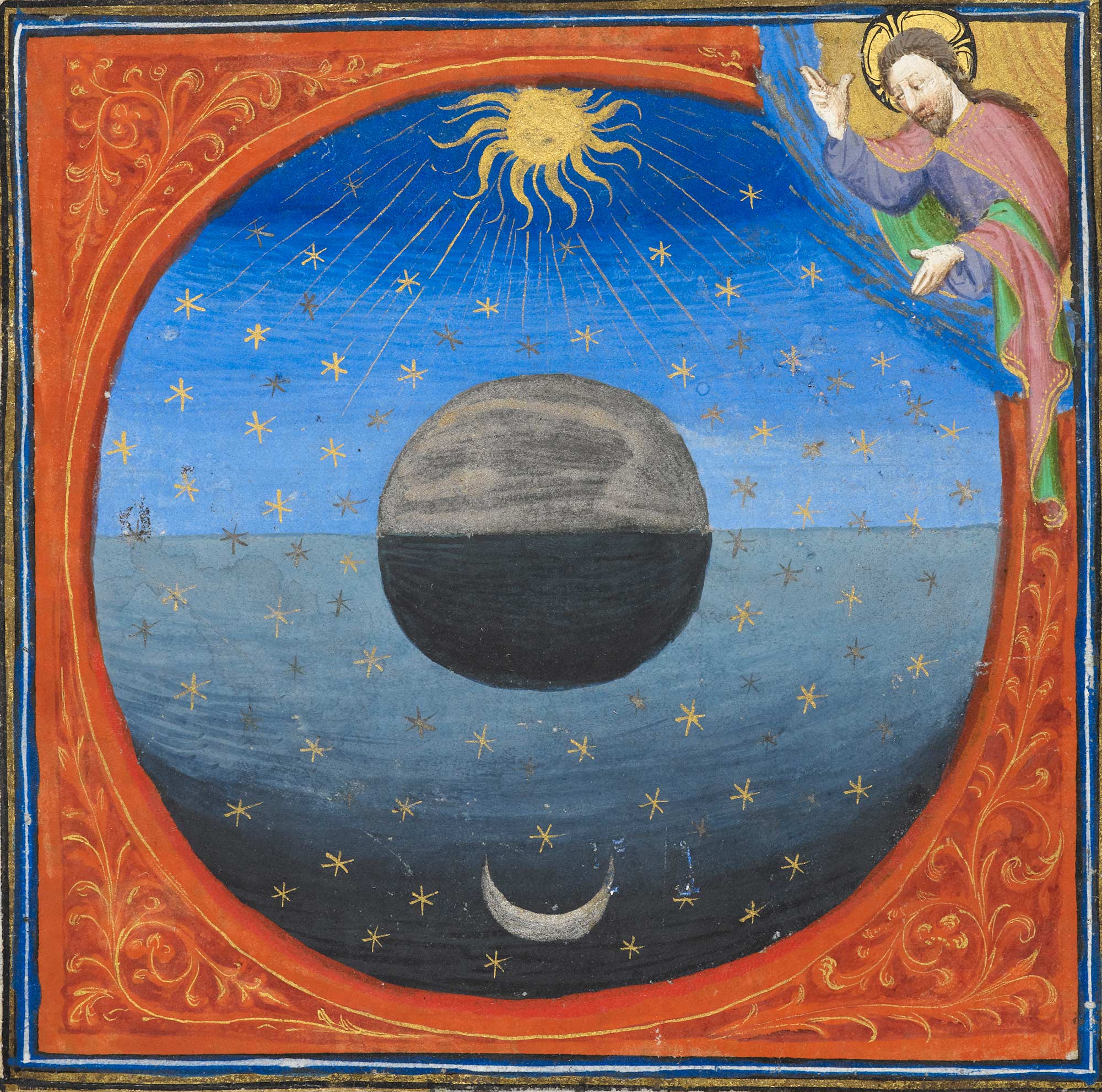

The fourteenth-century writer Geoffrey Chaucer offered a captivating vision of our planet as viewed from afar, defeating its gravitational hold through poetry. His narrative poem Troilus and Criseyde describes the globe as beheld from great distance, though the price of such a perspective is death. The Trojan warrior Troilus perishes in battle then experiences the sudden soaring of his soul. Liberated from the bone and flesh that kept him earthbound, he rises swiftly through the atmosphere, past the shimmering stars to arrive at the very edge of the cosmos. Here his spirit experiences a stability and harmony impossible from below, where every view is from the vexed and messy middle of things. Levity takes on a double meaning, a lightness that enables the spinning world to be glimpsed as distant home and a mirth that comes from no longer feeling the heavy force of terrestrial attachment. When Troilus dies, writes Chaucer, his spirit rises beyond the turbulence of the known world. A heavenly melody fills his ears. He is overcome with bliss as he looks down upon “This litel spot of erthe that with the se / Embraced is” (“This little spot of earth that is embraced by the sea”).1 Everything that he has known—the turmoil that has been his life as well as the matter of the poem—recedes far from view, diminished into a small but beautiful orb, land and ocean in lasting embrace. Troilus laughs at the heaviness he once felt, laughs at the gravity that works on all who are bound to the Earth, denied his capacious point of view. Celestial perspective has a way of making merely human concerns vanish.

© British Library Board (Additional 11639, f. 517)

© British Library Board (Additional 18856: f. 5v)

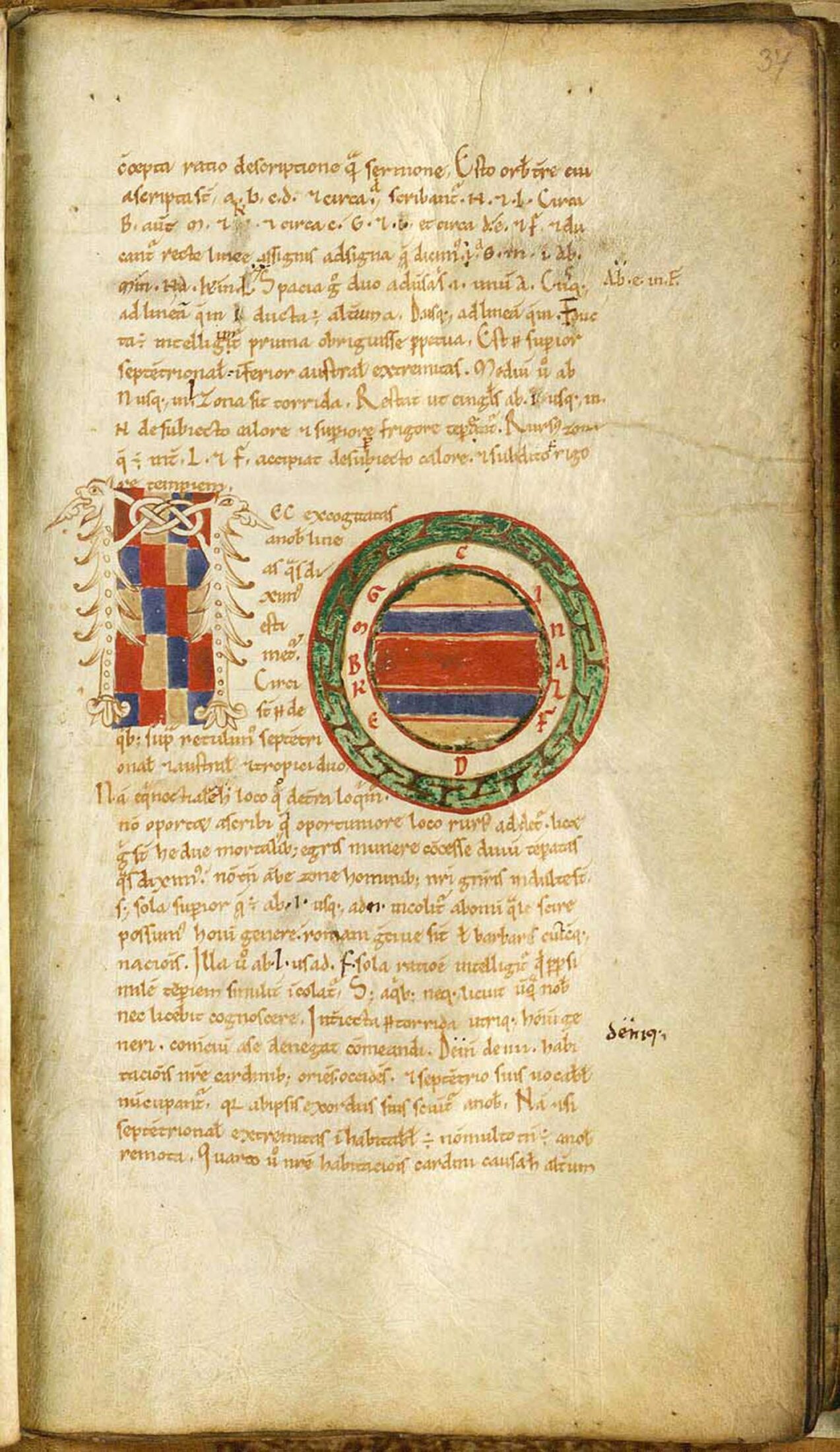

How could we have imagined the Earth as round without envisioning ourselves above it, looking down? The curve of the globe is too vast otherwise. When our transportation is by way of feet, horse, or sail, we can see only arcs and hints, not spheres. In the Middle Ages, the impulse to imagine the sun and the moon as they rotate around the Earth was also an invitation to envision what our home looks like when viewed from their skybound perspective. Along with this distant prospect comes a feeling. To inhabit a viewpoint outside and above the Earth offers an escape from the difficulties of living there. For as long as humans have understood the Earth as round (which is to say, pretty much throughout Western recorded history), we have also dreamt a perspective from which our home can be glimpsed from far above, often as a way of feeling less attachment to that complicated home. Medieval authors like Chaucer inherited one possible frame for that perspective from the Roman writer Cicero, who described a dream that the statesman Scipio Africanus the Younger had in his youth. In the Middle Ages, this vision was available within a detailed commentary on the cosmos composed by Macrobius, who used its imagining of the Earth from above to describe the shape, form, and expansiveness of the globe when beheld at great distance. In his sleep Scipio is visited by his grandfather, an illustrious military man, who grants his relative a view of Rome from the edge of the heavens. To the soundtrack of the planetary spheres and surrounded by the shimmering Milky Way, Scipio peers down at the Earth become a radiant globe, his city almost nothing upon its surface. The world’s various climates resolve into five bands: two white polar ice fields, top and bottom; two temperate and habitable zones on either side of the equator; and a torrid band of desert dividing the northern and southern hemispheres. In medieval manuscript illustrations, this Macrobian Earth (as it is called) can resemble a small Jupiter, vivid with planetary stripes. When he awakens from his dream, Scipio is fortified with proper Stoic contempt for worldly things. After escaping Earth’s gravity, if only in slumber, all that unfolds along its surface loses weight and hold, coming to seem a short-lived storminess that the proper mind should rise above.

Our desire to be less earthbound, at least during the space of a dream or a science fiction film or a medieval poem about the last days of Troy, is a yearning to escape entanglement in a world that exceeds us, vexes us, weighs us down—and yet remains intimate to our thoughts and stories. We never quite manage that escape into levity, at least not for long. Scipio the Younger rises above it all to gain new perspective, but that does not stop him from waging war on Carthage. He razes the city, sows its fields with salt, obliterates its future.

© Bibliothèque nationale de France (Manuscripts, Fr.9140 f.243v)

“Macrobian Earth”

© Det Kongeleige Bibliotek (NKS 218 4°)

The missions that NASA has sent to the Moon and Mars culminate long haunting dreams, offering a propulsion out of terrestrial life that was realized first through the technology of narrative and only later through actual space flight. Scipio beheld a Striped Marble rather than what the Apollo astronauts called a Blue Marble, but both perspectives arrive from an enduring desire to view the Earth from above. In the course of writing a book called Earth, planetary scientist Lindy Elkins-Tanton and I came to realize that imagining the planet as a beautiful object suspended in space is an ancient impulse. Those who inhabit this remote and aloof point of view frequently assume that when viewed from afar our luminous home will make us less arrogant about our place upon its vast surface. Suddenly unified by a shared sense of planet, we Earth dwellers might realize that we form a borderless community inhabiting a singular home. The Blue Marble image from the Apollo 17 mission is the most reproduced picture in history and a frequent symbol for ecological causes. You can’t have Earth Day without it. Yet just as Scipio sailed to Africa and destroyed a rival civilization after his thrilling planetary view, an image of the Earth as a marble or spaceship does not seem to be achieving much when it comes to treading upon its surface more lightly, or imagining ourselves a planetary collective. The Apollo 9 astronaut Russell Schweickart beheld the Earth from above during a spacewalk and wrote about the experience with contagious awe:

There you are. Hundreds of people killing each other over some imaginary line that you’re not even aware of, that you can’t see. And from where you see it, the thing is a whole, and it’s so beautiful. You wish you could take a person in each hand, and say, “Look. Look at it from this perspective. Look at that. What’s important?”2

Despite the shared and glorious perspective that the planet from space offers, few of us seem able to accept its invitation to community or environmental care, at least for long. National boundaries vanish from afar. Yet even when Rome, Troy, Melbourne, and Nuku’alofa shrink to dots contained within imaginary lines, war and resource abuse and global devastation continue. Small interests always seem to trump shared, global concerns. Now that we know we have entered the Anthropocene, the age when human action has unmistakably altered the climate and we are readable upon its geological record, how do we safeguard our planetary home and ensure that it remains inhabitable for all its dwellers?

We ask big questions. We imagine capacious outlooks. And yet we remain earthbound. Can the imagination trigger action? Can enlarged perspective keep us from despair? What are the stakes of striving to view the Earth as if we were gods? Is the attaining of such perspective a comprehension, at last, that we are Earthlings belonging to a unified planet in the same way that mountains, clouds, animals, and oceans belong? Or is the desire to transcend the Earth, to rise above it literally and metaphorically, simply an attempt to exult in a dangerous fantasy of freedom from gravity? Maybe the problem is that we have never learned to inhabit more than one perspective at the same time. The best answer to most “either/or” questions lies, I have found, precisely in the middle, refusing the stark choices they frame. Is the Earth best viewed from above or from the thick of things? What if we answer that with a yes, affirming rather than deciding? Earthbound perspectives engender skybound prospects. We depart from the radiant Earth, look back, and realize that we are a small part of a vast cosmos. At our best, we refuse to forget this insight, refuse to return to small ways of dwelling. We refuse to build gates and walls. We offer expansive welcome. We create for ourselves and our fellow creatures a capacious sense of home.

© British Library Board (Yates Thompson MS 36: f.131r)

The curve of our planet is an invitation to view the Earth from above, from a perspective that both beckons and escapes. Gerald of Wales identified this pull as a constant celestial force. Chaucer and Cicero thought of this attraction to distant perspective as the gravity of the heavens, the lightness of being. When we build a ship and journey into space so that we can see the Earth rise as if it were any other celestial body, or when we view the planet in its entirety as a Blue Marble or Pale Dot, we give in to the same tug. Perhaps the time will come when we can imagine ourselves journeying skyward without also giving up on the lived difficulties of this little spot of Earth.

Every flight touches ground again. I have almost arrived in Los Angeles. The North American shore is visible from my window now. The dawn is streaked with rose, orange, and red. The sun is just emerging through the smoke of unprecedented wildfires. These are not easy times to be Earth dwellers.

Every dreamer awakens to the world as it is, even as that dreamer also possesses a vision of a world that might be. Every perspective, no matter how distant, is earthbound, clasped by the disorienting force of the only home we will ever have.

- Geoffrey Chaucer, “Troilus and Criseyde,” in The Riverside Chaucer, gen. ed. Larry D. Benson, 3rd ed. (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1987), 5.1815–6.

- Robert Poole, Earthrise: How Man First Saw the Earth (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008), 165–66.