Emily Polk lives and writes on a small island east of San Francisco and teaches environmental writing at Stanford University. Her writing and radio documentaries have appeared in National Geographic Traveler, The Boston Globe, National Radio Project, Whole Earth Magazine, Creative Nonfiction, and Aeon among others. This essay is adapted from her forthcoming book Wild Grief.

Bees have long been witness to human grief, carrying messages between the living and the dead. Finding solace in the company of bees, Emily Polk opens to the widening circles of loss around her and an enduring spirit of survival.

I drive under the highway overpass at 30th Street, past two women in hijabs walking swiftly, a Chinese man with his bike waiting at a bus stop, an “Exotic Market” promising cheap groceries. Boarded storefronts tagged in colorful graffiti offer a secret language of urban scars. I pass a caravan of rusted school buses and flat-tired RVs occupied by old men wearing the skin of the city on their faces, and park next to a blue tent that smells like piss and wild sage pitched in the middle of a sidewalk. In this city of beauty and rubble, where everything good and everything bad about it is true and sometimes at the same time, I am looking for a famous beekeeper from Yemen.

I make my way toward “Bee Healthy Honey Shop,” where just beyond the front window, makeshift shelves in the shape of wooden hives hold beeswax candles, soap, and jars of honey. On the side of the store, a mural titled “Happbee place” shows a painted beekeeper kneeling next to colorful hive boxes. Muslim prayers spill out the front door and into the street. The shop is a sanctuary where everybody prays to the bees—with good reason. The oldest bee fossil dates back more than a hundred million years. These little creatures were flying under the noses of dinosaurs while humans were still stardust. Today there are more than twenty thousand known bee species, hundreds of whom make their home in the San Francisco Bay Area, where I have lived on and off since I was twenty-three years old.

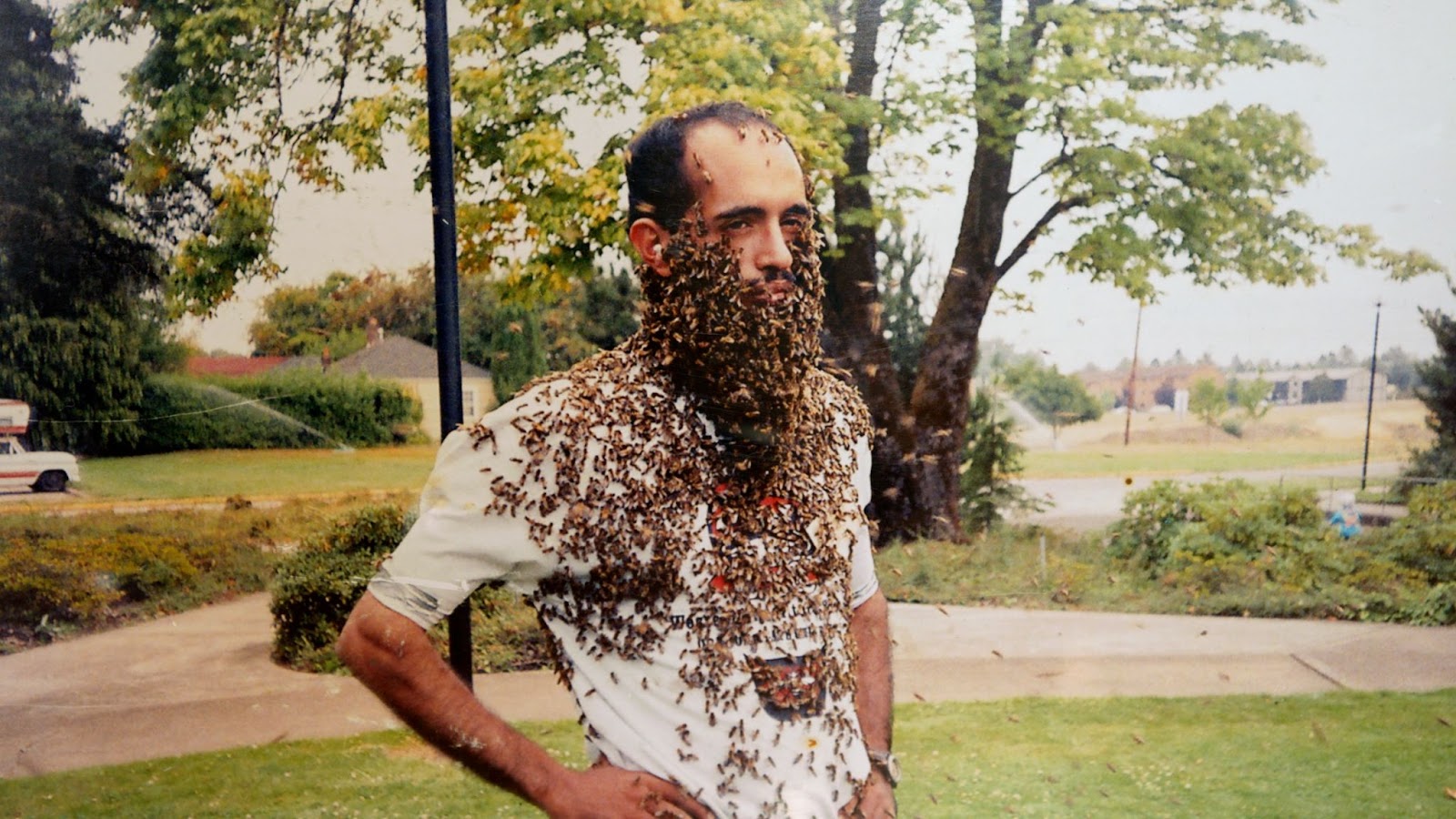

Inside the shop, just behind the counter, is a large blown-up photo of a young man whose lower face, neck, shoulders, and chest are covered in thousands of bees. His dark eyes stare solemnly, his naked forehead exposed like a bare moon in a galaxy of bees. I can’t take my eyes off the photo. I want to meet this solemn man, a legend I’ve only read about. Mostly I want to be in the presence of somebody who can speak for bees. Not about bees—I’ve already met plenty of people who can do that. I want to meet the humans who can speak for them. I’ve heard they are in the mountains of Slovenia and in the Himalayas of Nepal. And also right here in downtown Oakland, California.

I HAVE LOVED BEES my entire life, though my love for beekeepers started when I was writing a story for the Boston Globe about the dangers of mites to bee colonies in North America. I drove out to Hudson, a conservative town in rural New Hampshire, to meet leaders of the New Hampshire Beekeepers Association. I arrived just in time to watch a couple of senior bearded men in flannel shirts and Carhartt pants transport crates of bees into new hives. I was completely entranced by their delicacy and elegance. They seemed to be dancing. I wrote of one of the beekeepers, “He moves in a graceful rhythm … shaking the three-pound crate of bees into the hive, careful not to crush the queen, careful to make sure she has enough bees to tend to her, careful not to disturb or alarm them as he tenderly puts the frames back into the hive. And he does not get stung.” I was not expecting to find old men dancing with the grace of ballerinas under pine trees with a tenderness for the bees I wouldn’t have been able to imagine had I not witnessed it myself. This moment marked the beginning of my interest in what bees could teach us.

HUMANS AND BEES have been in close relationship for thousands of years. The Egyptians were the first to practice organized beekeeping beginning in 3100 BC, taking inspiration from their sun god Re, who was believed to have cried tears that turned into honeybees when they touched the ground, making the bee sacred. In tribes across the African continent, bees were thought to bring messages from ancestors, while in many countries in Europe, the presence of a bee after a death was a sign that the bees were helping carry messages to the world of the dead. From this belief came the practice of “telling the bees,” which most likely originated in Celtic mythology more than six hundred years ago. Although traditions varied, “telling the bees” always involved notifying the insects of a death in the family. Beekeepers draped each hive with black cloth, visiting each one individually to relay the news.

While bees have long been understood to be conduits between the living and the dead, bearing witness to tears from God and the grief of common villagers, less is known about the grief of bees themselves. Can bees feel sad? Do they feel angst? Among the many roles honeybees play in the hive—housekeeper, queen bee attendant, forager—the one that catches my attention is the undertaker bee, whose primary job is to locate their dead brethren and remove them from the hive. (Depending on the health of the hive and its approximately sixty thousand inhabitants, this is no small job.) My beekeeper friend Amy, who, like me, has loved bees since she was a little girl, tells me over lunch that one of the craziest things about this is that there’s only one bee doing it at a time. “Just one bee will lift the body out of the hive and then fly away with it as far as possible,” she says. “Can you imagine lifting one whole dead human by yourself and carrying it as far as you can?” We marvel over this feat of spectacular strength. “It’s always the females doing it,” she adds, which makes me smile, because all worker bees are female. The male drone bees only number in the hundreds and their only purpose is to mate with the queen bee, after which they die.

But I want to know if the undertaker bees feel anything while they are removing dead bees. Do bees have emotions?

A few years ago the first study to show what scientists colloquially refer to as “bee screams” was published. Scientists found that when giant hornets drew near Asian honeybees, the honeybees put their abdomens into the air and ran while vibrating their wings, making a noise like “a human scream.” The sound has also been described as “shrieking” and “crying.” According to scientists, honeybees’ “antipredator pipes” share acoustic traits with alarm shrieks and panic calls that mirror more socially complex vertebrates.

I am not surprised at all that a tiny insect also screams in a way that has been compared to a human scream. I don’t think it has anything to do with social complexity or being a large vertebrate, but rather something much more primal and universal to the experience of being alive. Every day for months after my baby daughter’s death I also felt compelled to scream. I wanted to scream at the dogwood blossoms outside my home in Massachusetts; I wanted to scream at the grocery cashier cracking jokes. I never associated the urge with being human. I felt it was what an animal did who was no longer safe in the world. When I read the study, the sharp edges of my own grief felt soothed by the underlying revelation—there are profound connections shared between living creatures, no matter the size of our brains, no matter how loud the sound of our screams.

I wanted to know more. Fifteen years ago my husband and I had taken our daughter off life support when she was three days old. The grief was gutting, like somebody put my nerves outside my skin and then cut each one, slowly. The only balm for the pain was to be with others who had been through something similar. Later, I sought comfort in the more-than-human world and what I might learn from how animals experience grief.

Melissa Bateson, a Newcastle University ethology researcher, and her team were some of the first scientists to discover that bees do actually have emotion-like states. Drawing from research on humans that showed that negative feelings are reliably correlated with expecting negative outcomes—(i.e., when something bad happens to people they continue to expect bad things to happen)—she wondered if the same result could be found in bees. So Bateson’s team trained their bees to connect one odor with a sweet reward and another with the bitter taste of quinine. The bees were then divided into two groups. One was shaken violently to simulate an assault on the hive, while the other was left undisturbed. The team found that the shaken bees had significantly reduced levels of dopamine and serotonin in their brains and that they were less likely than the undisturbed group to extend their mouthparts to the quinine odor and similar novel odors, as if they were expecting a bitter taste. They were stressed and anxious and these feelings were biasing them to predict a negative outcome.

On an early morning Zoom call, Bateson is quick to tell me that ethologists are always trained to accept that questions about emotions in animals or anything to do with their subjective experience are off limits. She doesn’t want me going all namby-pamby in my thinking. Scientists can’t claim to know the emotion of an animal, because animals can’t actually report what they are feeling in a way that can be reliably measured. But scientists can measure changes in animal physiology, cognition, and behavior.

“One way of going is to say, well, we should measure the things that we know tend to be correlated with feelings in humans,” Bateson says. “So if the animals do have subjective feelings, maybe they’ll be, you know, equally miserable if their cognition looks that way and their physiology looks that way. So that’s the scientific rationale behind it. But…”

On the screen she is shaking her head. Her pleasant face has grown tighter, more serious. She doesn’t want me to get this wrong. I have the feeling she thinks she’s talking to Winnie the Pooh.

“I mean it’s quite possible that [bees] could have these judgment biases, and there is nothing going on in terms of their subjective feelings at all, because I think we can tell a very good story about why those biases are functionally advantageous,” she says. “When you’re in a bad state, it’s probably a good thing to expect more bad stuff to happen to you, or to expect less good stuff to happen to you. That’s an adaptive shift in your decision-making. So it makes total sense that bees should display that kind of change in their behavior.”

I don’t say aloud what I am thinking: Is this not also how we might think about the purpose of grief? Can the active process of grieving not also be functionally advantageous? Should we not understand how to adapt our behavior in the face of sorrow, or expect “less good” while we are tender and vulnerable so that we can brace ourselves for handling what other threats may come our way? If it is helping them, does it matter if a bee knows it is sad?

While bees have long been understood to be conduits between the living and the dead, bearing witness to tears from God and the grief of common villagers, less is known about the grief of bees themselves.

I FIRST HEARD about Khaled Almaghafi, the bee-covered man in the photo, years ago when our Bay Area Transit System (BART) tasked him with removing hives found in various locations—from the train yard to the rails—and relocating them where they could continue to thrive. In the documentaries and news pieces that have covered his life over the years, I was struck by the way his own reverence for bees has been passed down for generations, from his father who began to teach him when he was five, to his father’s father before him, going back at least five generations and more than a hundred years.

I am holding a jar of his honey in my hands when Khaled walks into his shop with friends. He is wearing glasses and a blue baseball cap. He has a mustache that reminds me of my father. His voice is gentle. The first thing he tells me is that bees are sacred in his culture. Indeed killing a bee is considered a sin in Islam. “What bees can do, their honey, it is a miracle God created,” he says. His Arabic accent makes me wish he didn’t have to translate his words into English for me. “From the smallest insect, he made medicine for human beings.” Khaled points toward a wall hanging above him. Inside a frame is an excerpt about bees from the Quran in Arabic. In the sixteenth surah, named “The Bee” or Surah an-Nahl, the bee is divinely inspired to flourish and to make honey, a benevolent substance with healing properties.

Khaled agrees to let me come with him on his next work appointment. He’ll be in Concord in a few days, about a half hour east from where I live, to inspect an apartment filled with bees.

ON MY DRIVE to Concord, the highway passes green foothills dotted with clusters of wildflowers and dozens of bee species partaking in their ancient foraging rituals. In fact, while I sit in my gas-guzzling car, fumbling with my GPS, many of the bees just outside my car window are using the Earth’s magnetic field to orient their way to more than five thousand flowers that they will pollinate, while bearing their own body weight in nectar they have collected. And they do all this while navigating substantial physical and psychological challenges: Before bees can take the nectar they must learn the mechanics of gaining access to the contents of the flowers with no two flower species being quite alike. Then there are the risks of finding flowers empty and the constant negotiations around figuring out when to keep searching (while keeping track of which flowers offer the highest rewards) and when to leave the area to seek more plentiful food. While doing all this, bees must be aware of potential predator attacks while also remembering how to get back home to the hive at the end of the day. They do all this every day, making life for us possible. And today they do it even while their colonies are dying in massive numbers. Some native North American bee species have declined up to 96 percent in the last two decades, and in 2023 alone beekeepers in the US experienced the second-highest death rate on record with an estimated 48 percent loss of their honeybee colonies in 2022–23.

There are a lot of reasons for their deaths. Pesticides and the mites mentioned earlier are to blame. But so is habitat destruction from increasingly extreme weather events, and starvation stress due to changes in flower blooming times, all of which threaten fruit, vegetable, and nut crops like apples, blueberries, and almonds. Scientists are only just beginning to find out how bees are reacting to warming climates.

Nathalie Bonnet, a senior at the University of California Santa Barbara, was conducting some of the first studies on the impacts of increased heat on bee species native to Southern California when I first reached out to her. Nathalie became interested in studying bees during an internship where she trained an AI learning model to recognize and quantify bee hairiness as an indicator of thermal tolerance using images of hundreds of bee species.

“Bee hairiness??!!!” I exclaim when we meet for the first time over Zoom.

“Yes! So there’s a bunch of bees that aren’t hairy at all,” Nathalie says, her eyes bright and animated. “They went into the hairless bee category. And then there was like one through five hairiness.”

I am eager to learn more, but mostly I want to talk to a young person. I want to know what young people are thinking about in the face of so much loss. Nathalie was the same age as my students, so many of whom were grappling with the grief of a rapidly changing climate. Was Nathalie learning something about surviving excruciating loss and change? Could I learn something too? Nathalie had spent the past year collecting bees, putting them in a heated incubator, and watching their behavior, monitoring when they drop into a heat stupor and lose control of their muscles, and when they die. At the time we talked she had sampled seventy-two bees, mainly collected near the UCSB campus and Santa Cruz Island, one of the Channel Islands.

She tells me one of the most interesting findings so far is the role of phenotypic plasticity—the bees’ ability to change behavior based on stimuli or inputs from the environment. Nathalie found that when the bees were collected at higher temperatures they had already adapted and so lasted a little bit longer in the hot incubators. But all of them had different ways of surviving. Some of which astonished her.

Some of the survival behaviors were physical; others, it seemed to me, could have been psychological. “Honeybees will kind of vibrate their abdomen because their flight muscles are in their thorax, they will actually thermoregulate by touching their thorax and their abdomen together to transfer the heat back and forth so that they don’t overheat,” Nathalie says. “And then you have some of the smaller bees who would be sitting there, looking like they’re giving up. But then you take the test tube out and they just start flying around.” She pauses. “They’re not done yet,” she says.

They are not done yet.

I ask Nathalie how she is making meaning of this in her own life as a scientist just starting out in her field.

“You know, I personally deal with a lot of mental health stuff,” she says. “So for me watching these bees … They have all these behaviors built in to survive and evolve. And so do we. I think that sort of helps me rise above it almost. Nature finds a way.” She pauses again for a moment, reflective. “I think a really awesome thing about my generation of scientists—there’s a lot less stigma around our mental health. At the end of the day we’re just people. We’re just people who are also trying to survive.”

Photo courtesy of Khaled Almaghafi

I WONDER IF BEES have been teaching the scientists who study them how to survive for way longer than we previously thought. When I read about the first major discoveries about bees, I was struck by the intensity of grief experienced by the scientists who made the discoveries. Charles Turner, one of the pioneers of insect social behavior, published more than seventy papers, among them the first studies to show that bees have visual cognition and the capacity to learn. But his life was marked with terrible sorrow. Even though he was the first African American to get his PhD from the University of Chicago in 1907, systemic racism kept him from ever getting a professorship at a university or getting the support or recognition he deserved—though many scientists in the years that followed would use his work as a foundation for their own research.

Biologist Frederick Kenyon, born the same year as Turner, in 1867, was the first scientist to explore the inner workings of the bee brain. According to Chittka, Kenyon drew the “branching patterns of various neuron types in painstaking detail” and was the first scientist to highlight that these “fell into clearly identifiable classes, which tended to be found only in certain areas of the brain.” While Kenyon’s illustrations are extraordinary, his own mind seemed to be in insurmountable pain. He was eventually committed to a psychiatric hospital for threatening and erratic behavior. For four decades he remained in an insane asylum, alone until his death.

I think about Nathalie spending hours watching her bees and I wonder if the scientists who lived in the centuries before her like Turner and Kenyon, working late at night by candlelight, ever whispered to their bees of grief. Did they, like me, ever long to become a bee themselves, to leave behind their human bones and broken hearts for small wings, long tongues for nectar, and feet that could taste? In the face of all they had been through, would one barbed stinger have been enough?

Maybe the lesson then was the same as it is now: We are all just trying to survive. We are not done yet.

AT THE APARTMENT COMPLEX in Concord I park next to Khaled’s truck. On the bumper is a sticker that says, “Beekeepers are real Honeys.” He is standing next to the property manager, a middle-aged woman named Mahida. She wants to show Khaled where the bees are. We walk around the side of the complex, but before we turn the corner Khaled says, “Ahh, I can hear them. They are over there.” I don’t hear anything, but as we move closer to the back I can just make out tiny little black flying things—like raisins with wings—buzzing around a window. As we get closer, the buzzing gets louder. “Look,” Khaled is pointing to a pipe next to the window. “They’ve made a home up in that pipe. That’s how they’re getting into the apartment.” He waits for a minute, watching them. The longer we look, the more bees appear. Thousands of them.

“Come, let’s go in the apartment,” Mahida says. “I can show you what they are doing in there.” I am hesitant to follow. I don’t want to violate anybody’s privacy. “It’s fine, it’s fine,” she says.

We enter a tiny studio. The tenant is not there. A loft bed in the living/bedroom leans against bare walls. A small couch runs perpendicular to the window. On a table is a huge bouquet of red roses and in the back corner a makeshift altar holds religious candles that are lit and burning. More flower bouquets rest next to the altar. Somebody is being remembered here. I’m trying to figure it out, trying to put the pieces together, the flowers, the burning candles, the altar, and the emptiness, when I see shadows moving on the cream-colored wall above the couch. The shadows, as dark as beads, seem to be trembling. I step toward them and see they are shadows cast by bees. “We’ll have to cut through the pipe up there to get to the hive,” Khaled is pointing toward the ceiling where the rest of the pipe is concealed. “They made their home in there.” It is a home where they are not welcome. Did the bees know there would be flowers on the table and more bouquets on the ground? Did they come before or after grief settled here? Have they brought messages from and to the dead? Khaled will take the bees from their home in the pipe and relocate them, probably near a farm about an hour and a half away, where he keeps most of his hives, and where he will care for and keep them safe. He is their transporter and their keeper, the wind that moves them and the river that takes them home.

Before we part, Khaled offers to show me another place in Oakland where he’s been keeping bees for more than twelve years. In twenty-five minutes I am in downtown Oakland again, about to enter another stranger’s yard. Persimmon trees greet us like orange sunsets as we walk up a stairway and cross over into a front yard where there are about a dozen hive boxes.

I ask Khaled if he misses his home in Yemen.

“My town where I came from is in the mountains, similar to the weather here,” he says. His wife came to the US fifteen years after he first arrived. They have three daughters and one son but most of their relatives are still in Yemen. I ask if he thinks he will go back to see his mother and other family members.

“The situation now is hard, but people do still travel back,” he says. “People adapt to the war. They adapt to the suffering.”

I want to know if he’s learned anything from the bees that has helped him with the suffering. After more than half a century with them, what can he tell me about the grief of bees?

“Nothing comes easy,” he says. “Some people will give up. But the bees don’t give up.” He says no matter what happens to them, though, they never stop giving. “I learned from them to be generous. The bees give us honey and they never ask for anything in return.”

Khaled sprays the hives with bee smoke, a sage mixture that calms the bees so he can check on them without alarming them. He takes off the cover of the hive and peers in. Upwards of sixty thousand bees live in just one box. I cannot help but feel that Khaled could call each one by name.

Watching him, I am suddenly hit with a pummeling sorrow. Sorrow for my country, which cannot imagine its way out of its brokenness; for a warming climate where so much life is being catastrophically destroyed. Sorrow for the lives of so many families suffering from endless war; for scientists who faced unspeakable racism, and the ones who struggle with mental health; for the mourning tenant with their altar of bouquets and burning candles; for the bees who give so much even as they continue to be decimated; for the searing pain of my own losses, thrumming in my bones like a living bruise, an ache for a daughter who will never return. But then the bees are buzzing around Khaled, thousands of them, like golden stars in hallowed autumn light.

“They are healthy, these bees,” Khaled is saying, a soft smile on his face. I start to smile too. I realize then that it doesn’t matter if the bees’ generosity and resilience is a response to or consequence of grief, or just inherent traits whose significance is amplified in the face of rapid planetary loss. For Khaled, it is all the same. They are alive! In their daily travels along Earth’s magnetic fields, in the ways they scream to protect each other, in the ways they adapt and persist in the face of loss—of land, of clean air, of familiar flowers—they show us what it means to survive. In the tenacity and grace of their daily lives, they survive. This is the miracle that connects me to the bees, the thread that connects all of us wild creatures who are still breathing—it’s not the inevitability of loss and grief, but the astonishing revelation that somehow we’ve managed to survive in the face of it.

“Look closely you can see where the queen laid the eggs,” Khaled says. “There will be new bees there.” He is covered in them, the promise of them, the song of them, their honey breath and ancient bodies. I am dizzy with the sight of it, the courage of it, of how much life is in front of me trying to survive as best it can all the time, the dizziness makes my head spin until I think I too must be the persimmon tree bearing her orange sunsets, the hive box filled with buzzing, the sage smoke and the bee itself, I am also the bee with honey breath in an ancient body, flickering in this short life for a half-breath of a second against the blue bowl of sky, and beyond that, eternity.