Sophie Strand is a writer based in the Hudson Valley who focuses on the intersection of spirituality, storytelling, and ecology. Her poems and essays have appeared in numerous publications, including Dark Mountain Project, Atmos, Braided Way, and Art Papers. She is the author of The Flowering Wand, The Madonna Secret, and the forthcoming memoir The Body Is a Doorway, as well as the creator of the popular Substack “Make Me Good Soil.”

Ibrahim Rayintakath is an illustrator and art director based in India. His editorial illustrations have appeared in The New Yorker, The New York Times, Wired, NPR, and elsewhere. He lives and works in Ponnani, a small coastal town facing the Arabian Sea.

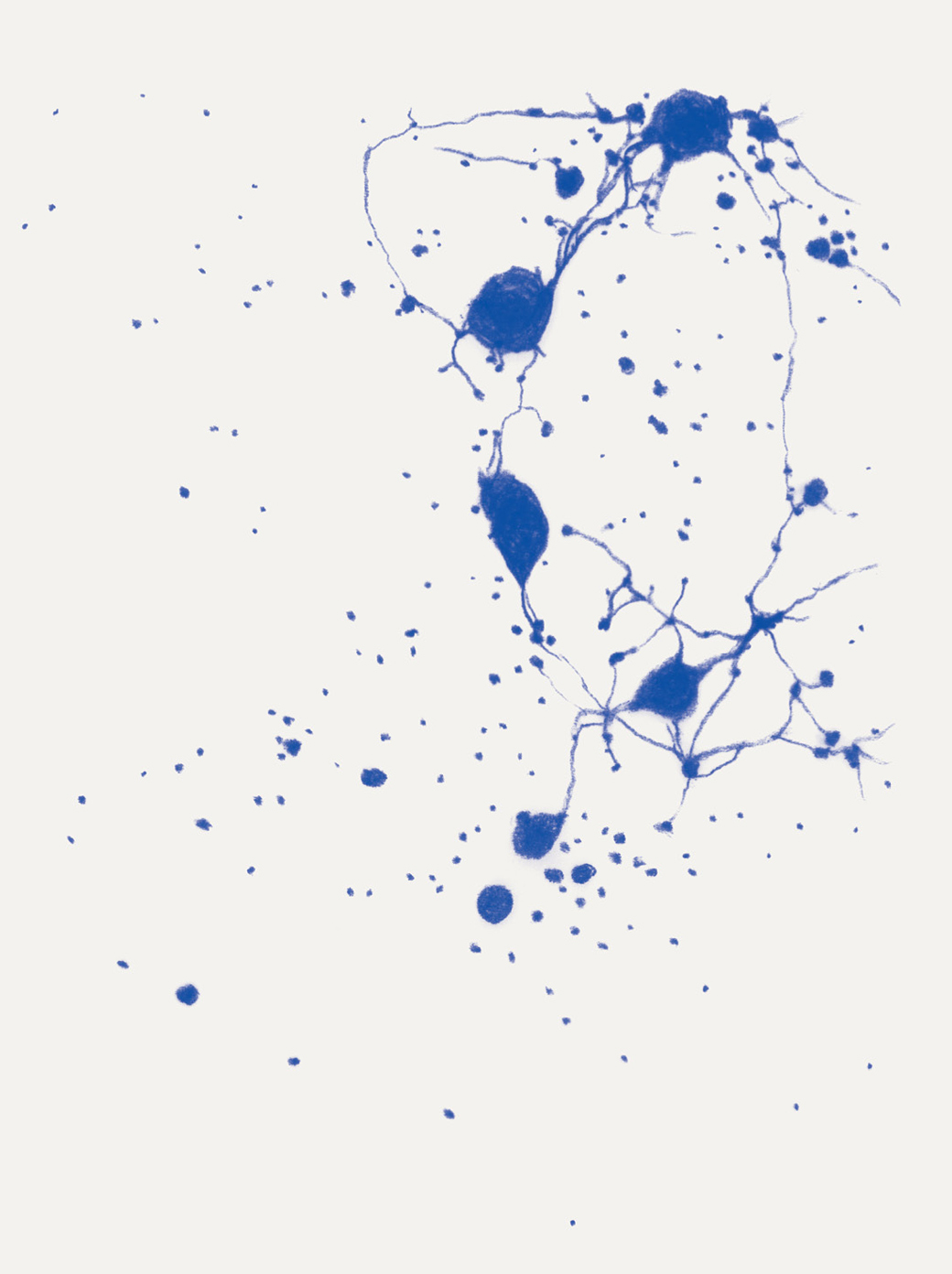

Opening up to “a supracellular state,” Sophie Strand uses her imagination to feel herself as part of the more-than-human: as river, as mycelial network, as the blood of a monarch butterfly.

Down by the river, I sometimes think I can scent the moment when the tide reverses and the estuary injects its salt response into a freshwater question. The air bristles, the wake of a passing motorboat cuts crisp Vs in the water. The salt in the air acts like salt in a soup: it enhances the flavor of the honeysuckle, the locust blooms, the sun-toasted cedar planks tilted against the boat-building shop. Mahicantuck, the river is called by the Munsee Lenape people, which means “the river that runs both ways.”

The ocean refluxes into the river. Is it, then, still a river? Or is it a brackish finger probing into the landscape? I squint, as if trying to mark the spot in the water where opposed currents intertwine like the snakes of the caduceus. The water surface, spangled with willow frond reflections, keeps its secret. But at my feet I spot something else: the velveteen dome of a mower’s mushroom pokes up from the grass. I bend down, noticing how the diminutive parasol structure disappears into the fine-grained soil. I know that although this fellow looks lonely, he is really less of a fellow and more of a swarming festivity below ground. Mushrooms are reproductive flourishes of fungal life-forms that live in soil (or wood) as threadlike, filamentous webs called mycelium. Mycelium is composed of long tubes of hyphae. One network might have thousands of different hyphal tips all capable of forking, fusing, foraging, and creating increasingly complex connections with other fungal systems and vegetal life-forms. I lightly press my finger to the mushroom, imagining my mind slipping like a yolk from the egg of my brain, into my arm, then strained through my finger into the mushroom’s damp body. Deeper still, below the fruiting body, my consciousness dives on mycelial threads into the underworld. It holds tight to roving nuclei as it travels through a chain of opening and closing doorlike pores.

If I had entered into an animal cell, I might have found myself profoundly confined, abiding by the strict rules of inner and outer, organelles bolted to the floor. But here in this mycelial network, I am not confined to one node. I can wander through the whole web. My ride is possible only because fungi are biologically unusual, confounding standard ideas of the cell and the self.

In 1665, Robert Hooke was the first to observe a microorganism under a microscope. It was his observations that, over the next two hundred years, informed the concept of the cell as a fundamental unit of multicellular lifeforms. The concept of the cell as a stable and foundational unit, though it applies to most of us, is not universally true. Many plants and filamentous fungi employ a type of cellularity much closer to verb than to noun. For example, while hyphae are commonly referred to as fungal “cells,” the term is misleading. A classical cell can be envisioned as a discrete bundle of protoplasm with one nucleus, neatly bounded by plasma and an extracellular wall—one bead in a necklace. But fungal hyphae behave differently. They create supracellular networks. Hyphae are separated by cross walls called septa. However, septa possess pores that open and close, creating a fluid passageway through a hyphal thread. For mycelial fungi, there is no discrete bead on the necklace. The necklace becomes a flume through which organelles and cytoplasmic material flow. A single hypha can, at one time, house multiple nuclei. And given fungi’s proclivity for promiscuity, those nuclei may not even carry the same genome as the original mycelial network. Fungal webs can fuse, exchanging nuclei and promoting genetic diversity.

I reach the end of a hyphal tip, bounce on a plush organelle called the Spitzenkörper that sits at the head, and scream as it cleaves beneath me, splitting off in two directions. A nucleus collides with me from behind, then another ramifies. The pressure passes my mind through the needle of another mind. I let myself fork and divide.

Many days I have sat at the river and imagined I am water. Fire. Air. Elemental. Matter flowing through other matter. A hummingbird. A sturgeon. The wet-eyed opossum under the barberry bush. The barberry bush. The Wolbachia bacteria pinwheeling through the colorless blood of the monarch butterfly. The exercise necessarily fails. But the empathy muscle it strengthens is crucial. In an age when anthropocentrism is fueling mass extinction and ecocide, it seems vitally important to practice thinking like other beings. Or even, when we feel ambitious, trying to think alongside elementals and the deep-time oscillations of entire ecosystems.

We have behaved like ordinary cells for too long, pretending there is no movement from the inside to the outside or vice versa. We have believed, for too long, that our minds belong to us as individuals. But advances in everything from forest ecology to microbiology show us we are not siloed selves but relational networks, built metabolically by our every biome-laced breath, thinking through filamentous connectivity rather than inside one neatly bounded mind. I think of the spider who, sitting like the iris inside a lacy eye, tugs and flexes and tightens her grip on different strings, creating an interrogative experience with web and with world. Scientists have likened this behavior to the activity of a brain itself, sifting through and reacting to stimuli. Each tug is a question, each returning vibration a reply. In this way spiders can sense which parts of their web attract more flies and focus their continued silk production on those areas. They can tell immediately when prey has been caught; and studies have shown that when webs are deliberately damaged, spiders perceive the damage and locate the spot, where they hurry to make repairs. Even more strangely, the extended cognition researcher Hilton Japyassú has shown that cutting a part of the silk dramatically shifts and disorients the behavior of the spider, seemingly imitating the effects of a lobotomy. This begs the question: Where is the spider’s mind? Is it inside the spider’s actual brain? Is it in the spider’s spinnerets or legs? Is it in the web itself?

As the cognitive philosopher Evan Thompson describes:

Part of the problem, however, comes from thinking of the mind or meaning as being generated in the head. That’s like thinking that flight is inside the wings of a bird. A bird needs wings to fly, but flight isn’t in the wings, and the wings don’t generate flight; they generate lift, which facilitates flight. Flying is an action of the whole animal in its environment. Analogously, you need a brain to think, but thinking isn’t in the brain, and the brain doesn’t generate it; it facilitates it. The brain generates many things—neurons and their synaptic connections, ongoing rhythmic activity patterns, the constant dynamic coordination of sensory and motor activity—but none of these should be identified with thinking, though all of them crucially facilitate it. Thinking is an action of the whole person in its environment.1

Thinking, then, is constituted less by an organ and more by a relational process. Life is an elemental verb, stitching us into other habits of mind, pouring our ideas into morphologies and minerals better suited to navigating complex systems.

I think my mind is not just in my body. It is in my entire web. My entire web of relations—fungal, geological, microbial, vegetal, ancestral—that weave together my specific ecosystem. Sometimes, in the morning, when I call on each of these beings in a practice I loosely name Gathering Counsel, I imagine that I am like a mycelial network below ground, opening up the septa pores in my branching hyphae. I am opening myself up to a supracellular state whereby my mind can pass through my threads of relation into the minds of woodchucks, black bears, chanterelles, and juniper trees.

Many days I have sat at the river and imagined I am water. Fire. Air. Elemental. Matter flowing through other matter. A hummingbird. A sturgeon. The wet-eyed opossum under the barberry bush.

Given that most ecosystems are experiencing anthropogenic disruption, this extended cognition is not always painless. A year ago, my favorite lake was “managed” by the local land conservancy. This involved cutting down more than three hundred trees, some of which were home to bald eagles I had known for years. The management program decimated the local beaver population and the diverse array of wildflowers that had clung like a Technicolor crown around its shoreline every summer. Now, every morning, when I go to summon that part of my mind, I find a blank. I think of the spider with its cut web and disoriented behavior. Part of my web has been cut. I cannot flow through my whole web of consciousness. My thinking becomes disorganized. When those trees were cut down, when those eagle nests were dislodged, where did that part of my mind go? It feels equivalent to the loss of a neurological function after brain injury. I’ve lost the ability to use my left hand. To distinguish faces. To recover certain words.

I gaze out at the River That Flows Both Ways and think of the countless Munsee Lenape who died right here, on these banks, slaughtered by the Dutch. I think of that frayed spot of the web. I feel their absence in my extended mind. I open up my septa to the nucleus of their void. If nuclei can flow both ways through opendoor cells in a mycelial network, maybe time can also flow both ways, refluxing backward from the future like the ocean sending its vein of brine back down into the Hudson and also flowing from the distant past. Can the Munsee Lenape who died here still reach me? And then, leaping forward, I ask the guardian angel of my own self: What next? How do we bear this?

I summon the supracellular not because I want to go on an adventure but because I earnestly want to think better. And I have a hunch that thinking better means leaking outside of the bounded cell, the individualized flavor of consciousness. In a similar vein, the Welsh Mabinogion’s legendary bard Taliesin recounts:

I have been a blue salmon,

I have been a dog, a stag, a roebuck on the mountain,

A stock, a spade, an axe in the hand,

A stallion, a bull, a buck,

A grain which grew on a hill,

I was reaped, and placed in an oven;

I fell to the ground when I was being roasted

And a hen swallowed me.

For nine nights was I in her crop.

I have been dead, I have been alive.

Whenever I read this poem, I think of how all poetry, all mysticism, all great wisdom comes from a willingness to leak into other being’s minds. To be a salmon. A stallion. A grain. To know that while we may superficially function as individuals, we are really part of a long-term project in supracellularity whereby all our physical matter flows and recycles and recombines. To be a better salmon, be a man for a while. To be a better man, be a river. To be a better river, let yourself be invaded by the nucleus of a distant ocean.

If a cursory study of somatics shows that we think with our entire body, then how much better could we think if we did so with our entire web of wild kin? I want to think and feel and weep and grieve with my whole multispecies, polynucleated mind. I want to let the yolk of my small desires slide into otherness. I want to nucleate a symbiotic quest for a better future. Throw open all the doors in my cells. Let my river run both ways.

“Supracellular: A Meditation” by Sophie Strand is adapted from the forthcoming memoir The Body is a Doorway: Healing Beyond Hope, Healing Beyond the Human, and appears in Center for Humans and Nature’s five-volume collection, Elementals.

- Evan Thompson, “Spring Forward or Fall Back: Changing Times for Neuroscience,”

Psychology Today, May 13, 2015, https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/wakingdreaming-

being/201505/spring-forward-or-fall-back.