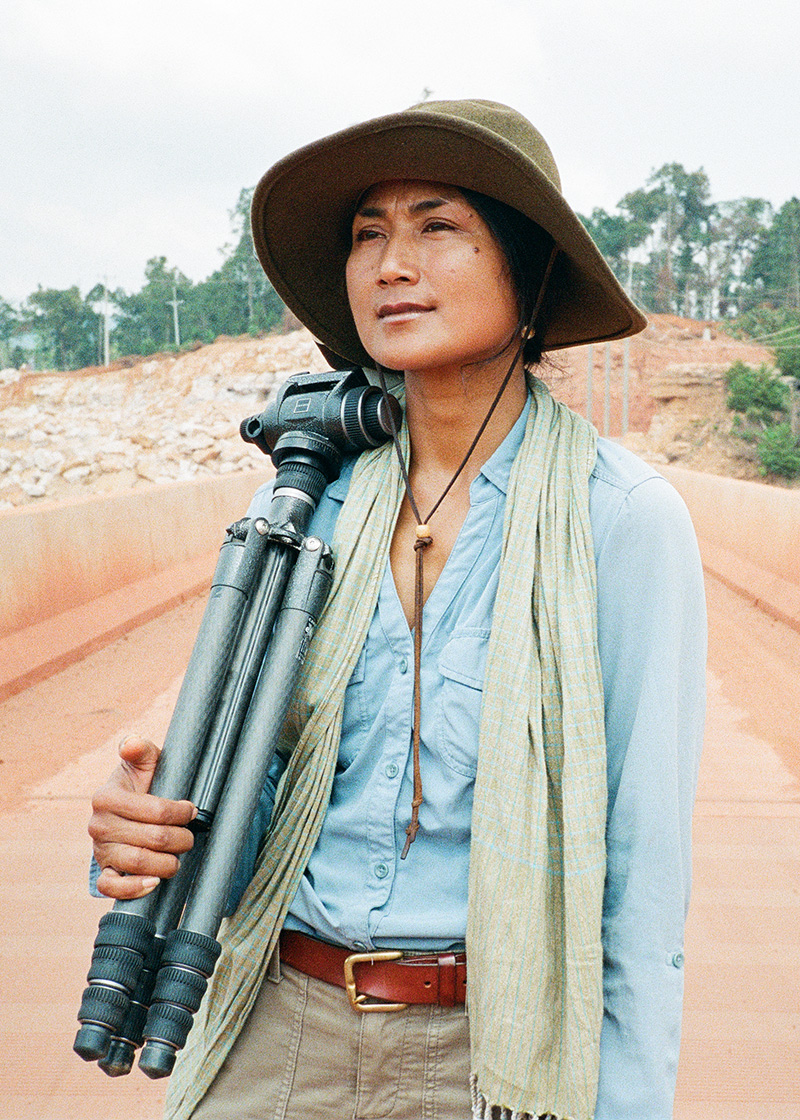

Kalyanee Mam is a Cambodian-American filmmaker whose award-winning work is focused on art and advocacy. Her debut documentary feature, A River Changes Course, won the World Cinema Grand Jury Prize for Documentary at the 2013 Sundance Film Festival and the Golden Gate Award for Best Feature Documentary at the San Francisco International Film Festival. Her other works include the documentary shorts Lost World, Fight for Areng Valley, Between Earth & Sky, and Cries of Our Ancestors. She has also worked as a cinematographer and associate producer on the 2011 Oscar-winning documentary Inside Job. She is currently working on a new feature documentary, The Fire and the Bird’s Nest.

Reconnecting with her homeland of Cambodia through the taste of Battambang oranges, yellow mushrooms, and chapchang snails, filmmaker Kalyanee Mam shares the land-tastes that helped orient her to a way of life deeply tethered to the land.

ជាតិ Cheate

In the Khmer language, the word for taste is រសជាតិ rosacheate. The word for flora is រុក្ខជាតិ roukkhcheate. The word for nature is ធម្មជាតិ thommocheate. And the word for country is ប្រទេស ជាតិ brates cheate. To know the plants, to know nature, to know the land and where you come from, you must know and feel the land-taste or the taste of the land.

WHEN MAAK, MY MOTHER, was pregnant with me in Cambodia, she ate lots of Battambang oranges. This was my first land-taste. Maak says this is the reason why my teeth are so nice. The skin of the fruit is smooth and green; when you slice it in the middle, it looks like the sunrise and tastes as sweet as honey. During the Khmer Rouge, there was no sugar to be found. Maak squeezed the oranges and stirred the juice over the fire and made sugar, which she used to make koh, a caramelized soup, with eel that Bong Makkara, my eldest brother, secretly hunted for in the river. Immediately after Maak gave birth to me, breast milk, warmed by the fire stoking beneath the house, flowed from her body and onto my lips. I wonder if I could taste those sweet oranges in her milk.

There is a saying in Khmer:

កើតនៅទីណាទងសុកកប់នៅទីនោះ

kaet now tinea tongsok kb now tinoh

Where you are born is where your placenta is buried.

The night I was born, nearly two years after the Khmer Rouge regime began, the moon shone bright and full over the small hut Paa had built for our family in the village we were forced to flee to. It was Paa who carried the placenta out to the back of the house and buried it. No incense or candles were lit. All religious ceremonies were forbidden during this period. While making his offering, Paa softly whispered a few blessings under his breath.

The placenta, which had nourished and given me life while I was in the womb, was now returned to the soil, to nourish and give life to the earth and connect me to my birthplace.

Photo by Kalyanee Mam

BEFORE THE KHMER ROUGE, our family lived in the city of Pailin just a few blocks away from the market. Paa was a teacher and gem dealer. He would bring home bags of raw sapphires and rubies that he and his team had dug from the land. Maak would say a prayer to our ancestors and the land spirits and place the gems beneath the house to protect us. There were gems everywhere in Pailin. Bong Kunthear remembers walking down the street and picking up gems from the ground. When the rain came, they would suddenly peek from the earth.

While Paa worked, Maak took care of the children at home and sold cakes and noodles in front of the house. Paa decorated our home with paintings, and in front of the house he planted hot pink bougainvillea, yellow sunflowers, and fragrant frangipani. Maak remembers she and Paa never fought, never expressed an unkind word to one another. They always talked things out.

After the Khmer Rouge fell from power in 1979, our family fled to Nong Chan at the border of Cambodia and Thailand. There, we thought we were safe. But one day Thai soldiers came and ordered us and hundreds of other families to pack our things and pile onto a bus. They didn’t tell us where we were going. Only at the end of the journey did we realize we had been taken to a mountain range known to be covered with land mines previously planted by the Khmer Rouge.

For weeks our family and hundreds of others walked through the jungle, stepping very slowly, one foot over the other. Maak slung a ក្រមា krama (scarf) over her shoulder and across her chest and cradled me close to her breast. Though still a baby, I barely cried. Reflecting on it now, I must’ve felt soothed and comforted by Maak’s heartbeat, which reminded me of the heartbeat I shared with her in the womb. Bong Kunthear and Bong Phalkun walked on their own, hand in hand, following close behind. Bong Sophaline and Bong Makkara, the eldest, carried our belongings, while Paa walked ahead of us making sure if there was a land mine, he would take the hit. It took us hours to walk only a few meters.

One day, out of nowhere, a young man appeared dressed in a soldier’s outfit, looking very polished and well-groomed, his hair neatly combed and parted to the side. He told Paa he knew the forest very well, and if we would follow him, he would help us out. We followed him for many hours until finally he disappeared, nowhere to be found. Because we remained connected to the land, the land spirits helped us, guided us to safety. This is how we found our way and survived, our feet walking in unison, our ចិត្ត chett, our hearts, in sync with one another and with the land spirits.

ចិត្ត Chett

In Khmer, the word ចិត្ត chett means heart. It also means mind. So in Khmer the mind and the heart are one. To មានចិត្ត mean chett is to have a heart, to be kind; សប្បាយចិត្ត sabbaychett is to have a happy heart, to be happy. To feel ពេញចិត្ត penhchet is to feel full of heart and satisfied. To feel pain in the heart, or ឈឺត្ត chhu chett, is to feel heartache.

WHEN WE IMMIGRATED to the United States, Paa suddenly found himself in a land where he did not belong, no longer aligned with the spirits of the land and unable to communicate his longing for his homeland and the dislocation he felt as he was forced to adapt to a new way of life and a foreign tongue. He felt ឈឺត្ត chhu chett. I remember he would often sit at his desk at home, in silence, large blue hardbound Khmer-English dictionaries neatly stacked and laid open, writing in the most perfect and beautiful Khmer and English script with black pens he always had handy, often clipped on his shirt pocket. I had no idea what he was writing, but it was clear he needed to express something, to find who he was in this new and foreign place.

In Cambodia, Paa’s role had been clear. He was the one who brought home bags filled with raw gemstones that Maak gave as offerings to the land spirits. He was the one who would walk in front in a jungle laden with land mines to keep us safe. But in the United States, he felt lost. His education had no value here, and he no longer knew how to provide for his family. He wanted so much to belong that he even changed his name, Sok Sann, which means “peace and tranquility,” to Peter. Without realizing it, he’d chosen a name that means “rock”—a firm ground to stand on. When he found a job as a caseworker at the Refugee Resource Center, offering care and support to young Southeast Asian refugees caught up in the juvenile justice system, his longing to be of service was so strong he continued to work there even though they were cheating him of his salary.

The more invisible and underappreciated Paa felt at work and in his community, the more he put pressure on us to do well in school, to achieve what he could not achieve, and to become visible—to have មុខ មាត់ moukh mout, the face and mouth recognition—in a way he felt he never would in this country.

I wanted to please him and tried to do well in school. I spent most of my time alone, studying and reading books. I had few friends. I never felt comfortable in my own body. I felt unrooted, unable to connect to anything in the concrete landscape of suburban Stockton, filled with strip malls and large warehouse shopping centers. Since I was a little girl, I kept a sprig of windmill jasmine from our backyard in a jar on the windowsill next to my bed. The scent transported me to a world where I belonged and felt safe. I didn’t know it then, but I was longing for a taste of the land of my birth, longing for nourishment from the soil of Cambodia.

I was longing for a taste of the land of my birth, longing for nourishment from the soil of Cambodia.

Photo by Kalyanee Mam

WHILE PAA STRUGGLED to plant himself firmly in this new soil, Maak kept us connected to our homeland. On the weekends, she took us to the ទីផ្សារ tiphsaear ក្រោម kraom ស្ពាន spean, or the farmer’s market under the bridge, where we shopped for Cambodian vegetables and herbs grown by Southeast Asian farmers—Hmong, Laos, Khmer, Vietnamese, Thai—who had also fled their homeland and were finding ways to reconnect with the foods that came from these lands. Maak taught us how to recognize and speak the names of ត្រកួន takoun (morning glory), ត្រប់ throp (eggplant), ម្រះ marah (bitter melon), ស្លឹកគ្រៃ sloekakrei (lemongrass), and all the different ជី chee, or herbs, that we flavored our foods with. Even though they were grown in California soil, these vegetables and herbs gave us a taste of our homeland. And although I couldn’t quite understand or appreciate this at the time, they were also helping to ground me in the land and community here.

When we arrived home, we would race to the kitchen and prepare our family meal. Maak would first make the rice, washing the grains carefully. You have to rinse the rice well, Maak told us, or the grains will stick together. The girls would help Maak chop up and pound the lemongrass, turmeric, galangal, kaffir lime leaves, garlic, shallots, and fresh chilies, which Paa used as a marinade for his grilled lemongrass beef skewers, or សាច់គោ. Bong Sophaline would clean the fish and cut it into large pieces with the skin and bones intact, which we made into a soup with lemongrass, lime leaves, garlic, saw basil, and fresh lime juice.

With a straw mat laid out on the floor, all nine of us would sit, our legs folded together, surrounding the food we had just prepared and all the fresh vegetables and herbs we collected from the farmer’s market. There were no individualized plates of food. There was no head of the table. We all dipped into the soup bowl with our spoons ladling out what we needed and never more than everyone else. No matter what challenges we faced as a family, food and the sharing of food always held us together.

ស្គាល់ មជាតិ Skal Cheate

In Khmer, to know where you come from is to ស្គាល់ មជាតិ skal cheate, or to know your taste.

ON MY FIRST VISIT to Cambodia since we fled our homeland as a family, I tasted everything I could find and that was shared with me—soft and custardy ធុរេន thou re n (durian); sweet and tart មង្ឃុត mongkhout (mangosteen); fragrant and fibrous ខ្នុរ khnor (jackfruit); fresh and luscious ផ្លែស្រកានាគ phle srakeaneak (dragonfruit); juicy and tangy សាវម៉ាវ savmeav (rambutan); honey sweet មៀន mien (longan); creamy and succulent ទៀប tiep khmer (custard apple); salty and pungent ត្រីងៀត trei gneatt (dried fish); sizzling and savory ត្រីចៀន trei chien (fried fish); mouth-watering កង្កែប kangkeb (frog legs) stuffed with lemongrass គ្រឿង kreung, or paste; rich and creamy អង្រង angkrong (fried flying ants). I devoured and savored every morsel. Each bite tasted so delicious, comforting, and heartachingly familiar. Each bite brought me closer to the intimacy with the land that I had craved growing up.

All my life Maak had given me the palate and the language to appreciate these foods, but for the first time, I was able to connect them to a place. All of these foods had a history and a home. And so did I. With each savor and sensation, I was beginning to reconnect with the place where I was born.

Shortly after that first trip to Cambodia, Paa passed away, and I didn’t know how to mourn this loss. Instead of taking time to grieve, I poured all my energy into trying to do what I thought would make him proud of me as a Khmer daughter. I graduated from Yale, but even this achievement didn’t make me feel ពេញចិត្ត penhchet, full of heart, and satisfied. That first taste of Cambodia had opened a small window in my heart and left me with a longing to understand my relationship with the land and water and the people around me. I knew that returning there would help me make sense of it.

For over two decades I traveled to Cambodia as a filmmaker, living with families in different parts of the country, connecting with plants, forests, rivers, and oceans I had never tasted before but somehow felt had always been part of me. On the banks of the Tonlé Sap, one of the largest and most diverse bodies of fresh water in the world, I filmed Om Mey and Om Ma gathering lilies and snails with their grandmother. Om Mey made a necklace out of the stems and blossoms for her little sister, Om Ma, and they giggled. With the lily stems, their mother made a sour soup with fish, ទឹក។ត្រី tuk trey (fish sauce), and freshly harvested jasmine rice. We dipped the lotus blossoms in a sauce made with ប្រហុក prahok (fermented fish) pounded with fresh chilis and peanuts. I knew where this fish, rice, ទឹក។ត្រី tuk trey, and ប្រហុក prahok came from—from the great Tonlé Sap lake, the beating heart of Cambodia. From this fish, rice, ទឹក។ត្រី tuk trey, and ប្រហុក prahok, I could taste the fresh water.

Photos by Kalyanee Mam

The more I gave my attention to the land and learned its ways, the more my sense of belonging became grounded in the place I was in.

In the jungles of Ratanakiri, I remember filming ten-year-old Cha digging for ដំឡូងជ្វា damlaung chvear (potatoes) with her mother, Sav Samourn, and then making a fire and setting a pot of green ចេក chek namvar (bananas) and potatoes to boil. My stomach rumbled and my mouth began to salivate. When the bananas and potatoes were finally cooked, Sav Samourn handed me a steaming banana and a piping hot potato. I popped them into my mouth, and I felt I had never tasted anything so rich, creamy, and luxurious. I knew exactly where these bananas and potatoes came from. I knew exactly how this red earth tasted.

In the mangrove forests of Koh Sralau, I filmed Phalla and her family foraging for chapchang snails and reeling in crab pots filled with crab. In the evening, Phalla and her family and friends would steam the snails and flash fry the crabs. And Phalla would pound fresh chilis, garlic, fish sauce, and sugar, and squeeze fresh lime into her famous ទឹក។ត្រី tuk trey Koh Kong. I knew exactly where the snails and crab came from. I knew the stories that were told while they picked the snails and reeled in the crab pots. I knew the person who made the sauce. Tasting the snails and crabs, I knew the taste of the ocean and the sand.

In Areng Valley, I connected with Reem Sav See and her family. This would be the first of many visits to the valley, where I would spend nearly four years living with and filming this family and their way of life, so intimately connected to the land, water, and forests. It was May, a time, See told me, when mushrooms were abundant there. She had just harvested yellow mushrooms from the forest and green leaves I would later learn the names of and learn how to forage and prepare myself. With the mushrooms and leaves, See prepared a delicately sweet and aromatic soup. It was cold and raining outside. I remember feeling the warmth of the soup travel down my throat and into my belly and feeling like I had just tasted a bowl of sweet, yellow sunshine.

With each taste I shared with the families and communities I lived with, I began to slowly orient myself to the plants and seasons, to the flow of the river, to the fall of the rain, to the dryness of the earth, and to a way of life I had not known before, so deeply tethered to the land. I noticed that the more attuned and aware I was, the calmer I felt, because I knew where I stood in intimate relation with everything around me. The more I gave my attention to the land and learned its ways, the more my sense of belonging became grounded in the place I was in.

The camera also became a tool that connected me and grounded me in the moments I was documenting. Looking through the lens took me out of my thinking and wandering mind and focused my attention within a frame. I felt my body melt and expand, embracing each moment that came to exist within me. Wherever I focused my attention and set my gaze, I experienced beauty and intimacy; and immersed in this beauty and connection, I found belonging. មុខមាត់ moukh-mout was no longer about my face and mouth being recognized by others, as Paa had hoped for us, but about recognizing the beauty of a particular moment, reflected in myself.

With the families, I wasn’t always looking for the most obvious examples of beauty. Often, I found pleasure filming the most supposedly mundane things. When I lived with See and her family, I don’t know how many times I filmed her washing dishes, washing clothes at the spring or well, cleaning fish, chopping wood, and cooking a meal over the fire. What I realized was that these scenes, simply through my recognition and appreciation for them, often transformed into the most extraordinary and wondrous moments. I realized I was drawn to these moments because they reminded me of Maak. By filming See I was honoring Maak and recognizing the gifts she had provided for our family all along. I learned that the simplest acts of care, either for the land or for our loved ones, are what I should be orienting my life around.

Even though I was slowly opening my heart to the land and to the moment, I couldn’t let go of the sense of duty and responsibility that Paa had instilled in me to contribute in some meaningful way. I had wanted to make impactful films that told the story of people living with the land and how their lives were changing from development and globalization. But what I realized after living with the families—especially See and her family, who live their lives so deeply connected to the land—was that I had so much more to learn and needed to just observe and trust the story that was unfolding before me.

Reem Sav See and Kalyanee Mam in Areng Valley

Photo by Jeremy Seifert

ON THE EVE of my fortieth birthday, after having traveled many times in Cambodia, I found myself lost on an island off the coast. I had been walking alone, exploring the island and the lush vegetation that grew near the water and in the forest. No matter how hard I tried, I couldn’t find my way back. It was late in the afternoon and I was beginning to walk in circles. Finally, I stopped walking. I returned to a patch of grass beneath a small grove of trees and decided to sit still and lay my body on the ground. I remembered See’s husband, Lath, telling me that when he’s in the forest he would lay his body directly on the ground and the spirits would come, create an impenetrable shield around him, and protect him from all harm.

I laid my body down on the cold dirt and looked up at the burnished copper clouds floating across the sky like nebulous waves. Two eagles circled high up in the sky, while sparrows and black-white-and-yellow-patterned butterflies fluttered just above me. I then sat back up again. Suddenly I saw six great yellow-and-black hornbills, each alighting, one by one, on separate branches of an enormous tree. A while later, five of them darted from the tree like a long, straight, unflinching arrow. A moment passed before the sixth one quickly followed. At that moment, I gathered my legs together, stood up, and somehow I knew I would find my way back again.

The sun had by now sunk past the horizon, emitting only a slight warm glow. I walked straight ahead, looked to my left, and quickly recognized a tall and towering tree that I had touched and admired and paid my respects to earlier, before I had lost my way. I walked towards the tree as if walking towards a brilliant light and eventually found the path.

I walked back in the darkness with no torch, no light, nothing to help me see but my memory of the path and all the plants and trees I had befriended along the way. Armies of fire ants bit and burned my bare and naked feet, but I trampled on, trusting the path would become clear again. When I finally walked out of the forest and onto the soft and sandy beach, I was greeted by a sliver of moon and Venus shining brilliantly just above, a starry pendant hanging above the heart of the vast and magnificent sky. I sank my body into the ocean and swam in pools of glowing phosphorescence. I felt completely loved and embraced.

Just a few days before, See had a dream in Areng Valley, 266 kilometers away from where I was. She dreamt I was on an island, wandering aimlessly lost in a forest, my hair completely disheveled. In this forest there was a huge tree, and a tiger stood beneath the tree waiting to protect me. If I walked any farther, I would have stepped into deep water and drowned. See told me later that the tiger is a spirit animal belonging to the land and people of Areng Valley, and because she loves me and feels so deeply connected to me, the spirit animal that protects her and her family also chose to protect me.

The Khmer word ទុកចិត្ត toukchet, to keep your heart with someone or something, means to trust. By entrusting your heart, you trust that you are supported, protected, and cared for. On the island, I was finally able not only to open my heart but also to give my heart and trust I was not alone. The trees, the moon, the stars, and even the fire ants illuminated my path and showed me the way. And the land and water spirits that had protected us on our walk through jungles laden with land mines continued to protect me too.

The placenta that was buried in the soil in Cambodia during my birth is also buried deep inside me—is part of the blood that flows through my veins—and continues to nurture and nourish me. Wherever I am, this connection is with me. I no longer need to try and fit in or belong. I can be and I am part of the land, wherever I may be. And when I remember this, I am no longer lost; I know who I am. As Maak reminds me: ស្គាល់ មជាតិ skal cheate, know your land-taste and where you come from, care for your loved ones and for the land, and you are home.

តាម លូវចិត្ត Tam Phlauv Chett

In Khmer, the word for depression is ខូចផ្លូវចិត្ត khauch phlauv chett, or the road or path to the heart/mind has been broken. To mend a broken path, one must តាម លូវចិត្ត tam phlauv chett, or follow the path to one’s heart.

NEARLY FORTY-FIVE YEARS after the fall of the Khmer Rouge regime, I traveled with my elder sister Bong Kunthear for three months across Cambodia retracing the path we took with our family during and after that period. Before our journey Maak handed us a manila envelope filled with loose pages of stories Paa had written down before he passed away. The time he spent in silence at the desk with large, blue hardbound Khmer-English dictionaries neatly stacked and laid open, he was writing stories of our family experience during the Khmer Rouge in a language that was foreign to him but that he knew his children and grandchildren would understand. He was sharing and unburdening his heart in order to find himself again. Now, he was helping us to retrace the journey our family had been through so that we could find ourselves too.

After the treacherous climb over the Phnom Dângrêk mountain range and through forests laden with land mines, our family made another long journey by foot from Preah Vihear province to Siem Reap, the site of the famous Angkor Wat temple complex. The journey took our family over three months to make. Paa wanted us to see the temples one last time before we returned to the border of Cambodia and Thailand, where we had previously been pushed out by Thai soldiers.

I had always viewed these temples as a symbol of Cambodia’s past magnificence and splendor. But on this last journey with Bong Kunthear, the temples suddenly felt different. Tucked away from the main temple complex, I found a small ancient ruin I had never seen before but that looked similar to the temple of Bayon, bearing the same image of Jayavarman VII arranged in four directions. Growing close and towering over the ruin was a giant chambok tree, tall and slender with a light trunk.

The temples in this area were dedicated to “the Protector,” both the Hindu god Vishnu and King Suryavarman II, a name which means “protector of the sun.” Looking at the monument with the faces pointed in four different directions, each face and mouth bold and distinct, I was reminded of Paa and the មុខ មាត់ moukh mout, or face and mouth recognition, he wanted for himself and for his children, how he held the role of protector in an outspoken way, wanting to be seen for his service.

Slowly, I turned away from the monument and gazed at the chambok tree. This tree, which offers valuable shade and nuts, reminded me of Maak and the love, care, and food she nourished us with over the years. She protected us discreetly, teaching us the skills we needed to nurture and nourish ourselves and our families. During a family visit in Stockton, Maak said to us, her children: “You are all grown-up and ដឹងខ្យល់ doeng khyal now. I have taught you well. You know your own taste, you can cook and make your own dishes, and now you are able to love and care for your own family the way I have loved and cared for you.” ដឹង doeng means “to know.” ខ្យល់ khyal means “wind” or “breath.” In Khmer, to come to maturity and understanding of oneself is to know the wind or to know one’s breath.

When I listen to the Khmer saying again—កើតនៅទីណាទងសុកកប់នៅទីនោះ kaet now tinea tongsok kb now tinoh—it becomes clear to me that buried with the placenta is also the ទង tong, or the stem of the placenta, the umbilical cord, the lifeline between mother and child, through which the child receives vital nutrients and breath. Although the umbilical cord was cut between Maak and me, this connection lives on, blessed by Paa, linking my breath to the earth and my taste to the land, wherever I may be. Now that I am older, I know where this breath comes from—from the earth, from the wind. I know this breath, therefore I know who I am.

Taste of the Land

Coming to know the changing landscapes of Cambodia changed by development through both her camera and the intimate relationships she forms with places and people, filmmaker Kalyanee Mam awakens an ancestral memory of the land that lies within.