Nick Hunt is a writer, journalist, and storyteller. His books include Outlandish: Walking Europe’s Unlikely Landscapes, Walking the Woods and the Water, Where the Wild Winds Are, The Parakeeting of London, and Red Smoking Mirror. His writing has also appeared in The Guardian, The Irish Times, The Economist, Aeon, New Internationalist, Noema, Literary Review, and Resurgence & Ecologist, among others, and has been included in The Best British Travel Writing of the 21st Century. Nick is a recipient of the Royal Geographical Society Journey of a Lifetime Award and is a contributor and co-director of the Dark Mountain Project.

Henry McCausland is an artist, illustrator, and author, whose debut graphic novel is Eight-Lane Runaways. His clients include The New York Times, The Guardian, The New Yorker, GQ, and Outside. He lives and works in the farthest reaches of South-West London, where there are exactly as many trees as there are buildings.

Nick Hunt ventures into the Forest of Dean seeking the unruly, twilight realm of the boar—a creature who brings him to the boundary between wildness and civilization, history and myth.

An hour before sunrise, I leave the cottage and walk into the woods behind, slipping in the churned mud of an uphill forest track. Wind roars in the trees and icy rain splatters my face, smearing my glasses so that all I see are silhouettes in wet murk. In the half light, less than half awake, the walk feels like a disturbed extension of sleep, and I am about to retreat and crawl back to bed again when I hear it—a deep earth-groan, followed by a bellow of fright or indignation. A heavy shape, densely black, heaves itself between the trunks; I hear the thump of hooves on loam as it crashes into the bracken. I only get a glimpse of it, but it leaves a reverberation of shock. Seconds later, it is unreal as a dream.

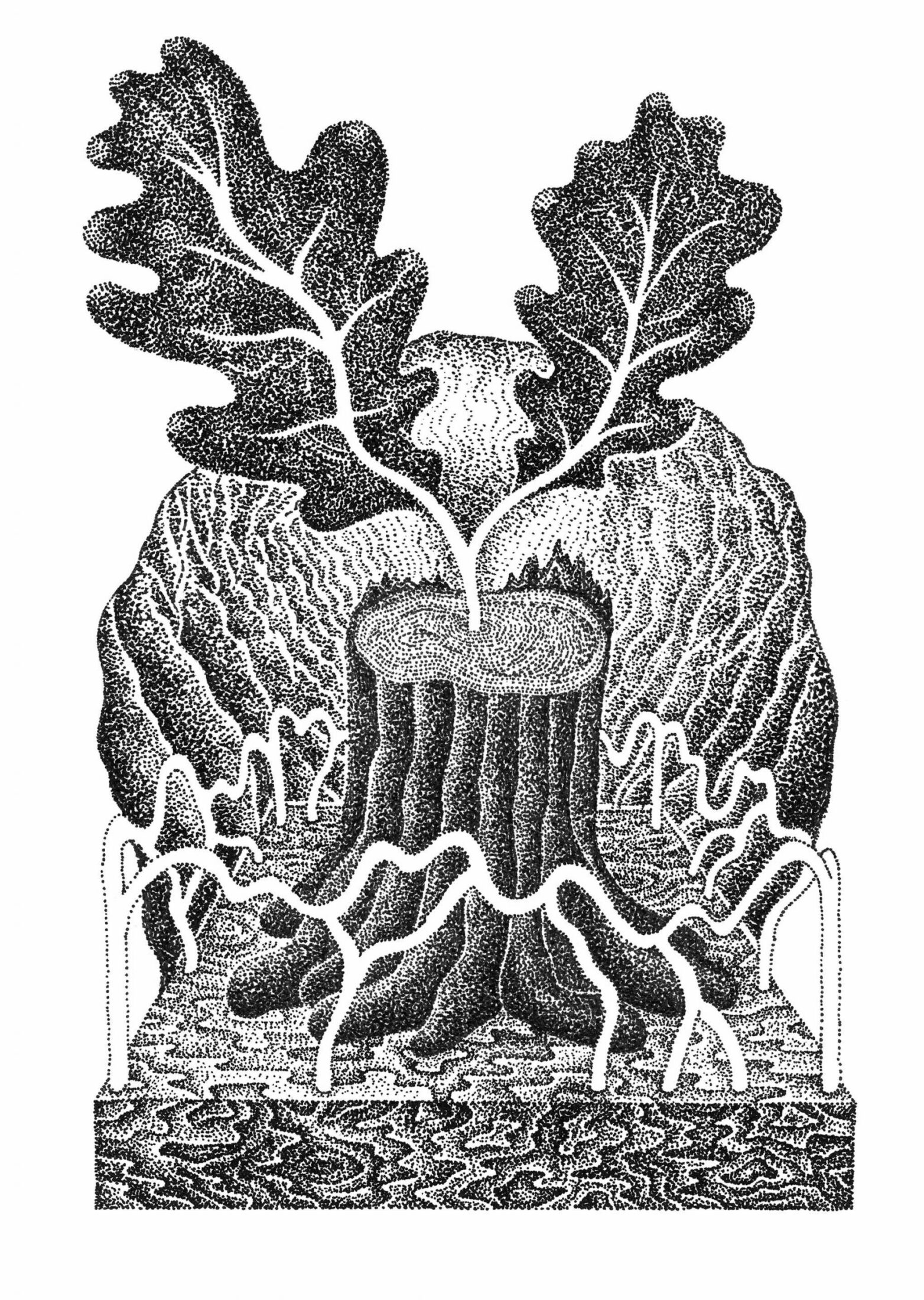

Twilight now, in a crunching dell where the leaf fall lies ankle deep. Centuries-old beech trees are scattered up the slope, their gray trunks scarred and muscular, far older than the plantation conifers in other parts of the forest. Signs are everywhere, once I’ve learned how to look: the mud marks around the boles of trees where something has rubbed and scratched itself; the imprints of small, sharp hooves that suggest substantial weight. There are puddles that are deeper than puddles, their banks mashed into liquid mud; and, of course, the broken turf along every roadside verge, the earth torn up and overturned. I notice the conspicuous lack of spring daffodils; the trail of impressive destruction through every forest village.

In failing light, I hop a stream and skirt a wide, marshy pond, alert to further clues. The knowledge that they are out there somewhere, perhaps not very far away, sharpens my senses and charges the heavy dusk with anticipation. Up the slope, something moves—too pale for what I’m looking for. A human form, seemingly naked, stoops and vanishes behind what looks like a low stone wall, then rises again, stoops again. I think I can hear singing. Unnerved, I retrace my steps until I have reached the road. Some things in the twilight are perhaps best left undiscovered.

The next morning I return to that spot to find a natural spring; my map marks it as St. Anthony’s Well—a stone cistern with worn steps leading down into clear water. Someone has placed candles here and a single long-stemmed rose. Later I learn that the ancient site is known as a place of healing. After carefully looking around, I take off my clothes and step in. The water is shockingly cold, but I manage to immerse myself three times, and when I come out again, my body is burning.

The forest feels clean and new, freshly charged with energy.

St. Anthony, I remember later, is the patron saint of lost things.

Unlike the last wolf in Scotland, famously killed in 1680 by Sir Ewen Cameron, the last wild boar in Britain departed without record. Historically they were hunted with dogs, hounded out of woodland thickets and dispatched from horseback with a spear, a sport known by the unlovely name “pigsticking.” There are tales of enraged animals driving themselves up the impaling shaft in order to gore their attacker as they died, and killing a boar was long regarded as a test of manhood. Whether they went extinct in the fourteenth, fifteenth, sixteenth, or seventeenth centuries, the oak, beech, and pine forests in which they had lived for thousands of years—whose ecosystems they had shaped with their industrious rooting and wallowing—were now as free of boar as they were of wolf or bear, emptied of any large mammal that could possibly be called dangerous.

It is not known exactly how boar returned to the Forest of Dean, the ancient mixed woodland in Gloucestershire where I have come to search. The most common explanation is that a small group escaped from a farm near Ross-on-Wye in 1999, where they were being bred for meat; another tempting rumor says they were freed by eco-activists. Five years later, a further sixty boars were apparently dumped near the village of Staunton, but no one seems to know how or why. What is known is that the two groups made their way into the forest and began to breed together, discovering a perfect habitat in which to hide, raise their boarlets, and thrive, supplementing the roots, tubers, and mast of a woodland diet with guerrilla raids on nearby farms, gardens, and allotments. Having been missing for hundreds of years, they fitted back into their forest home as if they had never been gone, and you can see that over the last twenty years parts of the forest have begun to revert—if you know what you are looking for—to their former condition in the pre-extinction ecosystem.

This evening the moon is full and the sky swells with light, casting the rows of young firs in a strange and sickly yellow. On the long forestry track to the east of Cannop Ponds, I have my second glimpse, and it is as abrupt as before: a crash from somewhere close to me, the urgent thundering of hooves, and two black shapes, sharp and low, thump across the path and vanish almost before my eyes can believe they were there. Instinctively, for some reason, I crouch low to the ground; beneath the low skirts of the trees, four stubby legs melt away. I have startled them, am startled by them, and the thrill remains with me as I descend the way I came, shocked not so much by their size as by their solidity.

Now the night feels rife with them. I hear another crash, a snap; a huff like an exhaled breath. Smaller paths lead off this track, but I am afraid to take them. At a certain indefinable moment, the complex chatter of roosting birds that has filled the forest stops, as if a border has been crossed. The daylight shift has ended, and the night belongs to boar.

Signs are everywhere, once I’ve learned how to look: the mud marks around the boles of trees where something has rubbed and scratched itself; the imprints of small, sharp hooves that suggest substantial weight.

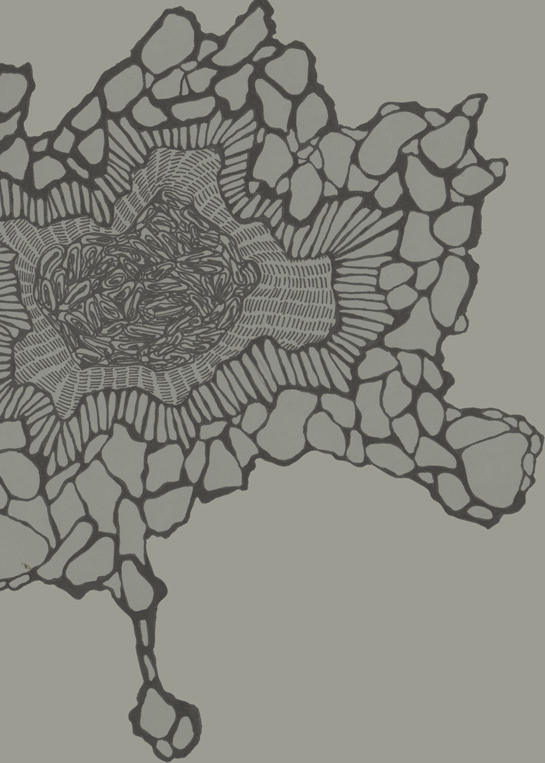

Not far away from St. Anthony’s Well is a rounded, wooded hill, where I find myself on another evening wander. There is something less than natural looking about the wide, concentric ridges that band the hill’s steep sides, a series of gigantic ripples petrified in the earth. Once my eyes have attuned to them, I recognize the defensive formations of an Iron Age hill fort, now covered by mist-shrouded beech and oak whose roots spread like tentacles, and once again I check my map: its name is Welshbury Hill. Bury derives from the Anglo-Saxon word burg, meaning “fortified place,” and Welsh derives from wealh, which simply means “foreigner”—a term applied by the encroaching Saxons to the native British population whose borders they were steadily invading and pushing west. Perhaps, in some forgotten time, the “Fortress of the Foreigners” was where some beleaguered Celtic kingdom made its last stand.

The modern-day border of Wales runs to the east of the Forest of Dean, and the divide between the two nations is still starkly defined. On one side lie cozy shires, patchwork fields, and English names; on the other rise the bare, sheep-nibbled mountains of Wales. Between the two stands Offa’s Dyke, supposedly built in the eighth century by the Anglo-Saxon king of Mercia to defend his lands from Welsh attack: an earthen rampart stretching north to south for almost one hundred miles, parts of which still delineate the border to this day. In the Middle Ages, this was the domain of the Marcher lords, appointed by English kings to guard what was then a highly militarized frontier zone; the picturesque ruined castles that dot the region were once the strongholds of a brutal occupation.

The Forest of Dean still has the sense of being a no-man’s-land, a place between one thing and another: not quite England and not quite Wales—or, rather, England but like no other part of England I could name. In the village near where I’m staying, two flags fly side by side, the red cross of St. George and the red dragon of Wales, and with this history in mind, the connection is obvious: St. George and the dragon, the vanquishing knight slaying the wyvern of the old world, impaling it—now that I think of it—with a spear, as on a boar hunt. The forces of order and civilization defeating the unruly wild. But in this wood between two realms, unruliness has returned.

For an area less than fifty square miles sandwiched between England and Wales, the forest remains surprisingly cut off and remote. Distinct cultural differences are harbored within the trees that separate the region from the rest of rural Gloucestershire, not least the right of Foresters—specifically, Foresters born within the Hundred of St. Briavels—to freely mine their own coal, a privilege granted by Edward I in 1296. Around 150 freeminers work inherited seams today, and a handful of small collieries are still in operation. Traditionally, Foresters also enjoyed the ancient rights of estovers (collecting firewood), pannage (pasture for their swine), and turbary (cutting turf). The forest today is still characterized by this peculiar mix—which is, I suppose, a very English mix—of feudalism and industrialization.

For although the forest is technically ancient, first protected as a royal hunting reserve, it is no pristine wildwood but a place long marked by industry. The fiery names of two of its main towns, Coleford and Cinderford, hold memories of charcoal burning, smelting, and coal extraction, and trees hide the scars of abandoned workings as effectively as they have buried the ramparts of the Fortress of the Foreigners. The popular cycle trail that runs from Drybrook to Mallards Pike Lake was formerly a railway line to facilitate the transport of coal, and the scenic viewpoint at New Fancy—which at first I think is another hill fort, many times greater than Welshbury Hill—turns out to be the spoil heap of a demolished colliery. In one clearing off the road, I glimpse the vans, woodsmoke, and drying clothes of a Travellers’ camp, a suggestion that freedoms might still exist here that the rest of the country has lost. Not quite wild, not entirely civilized, the word “feral” feels most appropriate to describe the contrasts and coexistences here.

It is an appropriate space for boar, in the in-between of things.

Fittingly for such a place, my first proper sighting does not occur in some primeval glade but along the perimeter fence of a working sawmill. I am making my way through spindly trees, the bushes around me littered with trash, toward a fierce crackling that might, I think, be caused by boar; but then I see a wall of orange flame and quivering heat haze. Sawmill workers are burning scrap wood, and I watch for a while before turning to go, and as I turn—there, there—I see two galloping black shapes, the pointed ears, the long snouts, the bristling ridges of their backs. They are like devices from heraldic shields come to life. Cautiously I follow them, but they have vanished fast, and all I find is a line of pointed hoofprints in fresh mud.

And now I see them whenever I walk, intuiting where best to look: on forestry tracks or along the borders of fields at dawn and dusk; in the shadows of spruce plantations where the ground is carpeted with moss; down pathways trampled through dry bracken leading to muddy wallows. When startled, they are shy and flee, but sometimes, from a distance, they linger to stare back at me, only emitting a warning bellow—something between a roar and a huff—if I try to get any closer. I do not push my luck. Like most wild animals, boar avoid conflict whenever they can, but if frightened, they can be aggressive, especially when a threatened sow has boarlets to protect.

One day I trace a path into a copse of low firs, my footsteps muffled on the needled floor, and find newly rooted topsoil and droppings that are still fresh. Instinctively I crouch again, and find myself almost face-to-face with a group of juveniles—half-grown, their hair still gingery brown, not the darker color that comes with age—watching me with shy confidence through the slender trunks. When I shift my weight, they move away, but when I stay very still, they tentatively regroup again, approaching and retreating like a herd of inquisitive cows. We watch each other for several minutes. Suddenly, for no reason I can tell, the main group turns and scampers off, leaving only the foremost boar, which seems to want more time to examine the clumsy stranger that has dropped into its world. In the end it is I who back away, while it stands its ground.

Perhaps even more than the presence of boar, what I notice most of all is how the fact of the presence of boar changes my relationship to the forest I am walking in, especially at dusk, when the shadows are growing and every fallen trunk takes on the ominous guise of a lurking hog’s back. I can’t pretend it is fear, exactly—can’t quite shake my modern Western sense of untouchability—but rather a tingling wariness, the shadow side of awareness. It feels like an England I know but don’t know, familiar and yet unfamiliarly charged, unfamiliarly alive.

The word I keep reaching for in my mind is “potent.”

Through this naturalist’s eyes, I start to see that the apparent mess the boar leave behind is a sign not of wanton destruction but its opposite.

A forest ranger stops at my cottage, having heard that I was interested in boar. I wonder if it’s his little spot I found in the woods two days ago—charred embers from a fire, a tree-stump seat, a tin mug, and whittled tools and implements hanging from branches of a tree—but I do not ask. The issue of boar is divisive, and he is careful about what he says. They have made many enemies, and local media is full of their hoggish depredations: plowing up gardens, raiding farms, causing traffic accidents, chasing horses and goring dogs; in one incident, apparently, even biting off a man’s fingertip. They have trashed village greens and the Yorkley cricket pitch—an audacious assault on hallowed symbols of Englishness—despoiled the lawn of a hospital, and infamously dug up graves around the church at Parkend. It is hard to imagine a swifter route to tabloid outrage.

In response to these and other concerns, the government has decided that the Forest of Dean’s population must be culled to a “manageable” level, from sixteen hundred to four hundred. They have no natural predators, and part of this quiet man’s job is to do the predating—something he does not enjoy but takes pride in doing well. There are poachers around, he says, and what he does is kinder than what they do. He believes that in appropriate numbers boar are good for the forest’s health, but when there are too many, they disrupt the ecosystem, destroying butterfly habitats and beloved bluebell woods. In particular they pose a threat to plantations, since much of the forest, after all, is run as a commercial enterprise; even the oldest oaks were originally planted to provide timber for the Royal Navy.

Later, in the north of the forest, I take a walk with a naturalist who gently disagrees. The overturned turf that we see is not destroyed; rather, it is disturbed, providing freshly plowed soil for new plants to take root, dispersing seeds, exposing worms for birds, and creating pockets of new habitat. Boar thin out bramble patches and are one of the only creatures that eat bracken—lining their stomachs with clay to neutralize the toxicity—which otherwise smothers the ground below, suppressing other plant life. Their industrious rooting and rummaging creates a wider mosaic effect that increases biodiversity and allows other species in.

And what of the beloved bluebells? Just look around, he says. It is too early for flowers, but he points out a profusion of shoots in even the most thoroughly boar-ravaged areas; bluebells and boar evolved together, after all, and the plants are resilient. He suggests that perhaps the only reason other woodlands in the country have shimmering carpets of bluebells in spring is the absence of boar. They are less a sign of abundance than of an imbalance.

Through this naturalist’s eyes, I start to see that the apparent mess the boar leave behind is a sign not of wanton destruction but its opposite. But it’s not hard to understand why others don’t view it this way. To the older population of the forest, who grew up with no boar—when daffodils bloomed along the roads and cricket pitches were left unmolested—the boars’ reappearance does not seem like the restoration of something ancient but, rather, something unnatural and new, a breakdown of the old order. What they are feeling is solastalgia for a pre-boar age.

The people who defended Welshbury Hill, and the people who supplanted them, would certainly have lived their lives in the presence of wild boar. In The Mabinogion, the Welsh national epic, the hero Culhwch—whose mother gave birth to him after being frightened by pigs, and who was then raised among swine—is charged with obtaining a razor, a comb, and scissors from between the ears of Twrch Trwyth, a monstrous boar that has destroyed a third of Ireland. These are the only tools strong enough to shave the beard of the giant whose daughter, Olwen, he wishes to marry; Culhwch must also obtain a tusk from the boar chief, Ysgithyrwyn. Enlisting the help of King Arthur, Culhwch crosses the Irish Sea and chases Twrch Trwyth back to Britain—the Island of the Mighty, as it is called—where it ravages the countryside and kills cattle, dogs, and men. They pursue it across Wales, until cornering it on the banks of the Severn, which marks the Forest of Dean’s southern boundary. Twrch Trwyth is killed, the giant is shaved, and Olwen’s heart is won. It is tempting to think that the Severn Bore—the localized tidal wave that rolls upriver throughout the year to heights of almost ten feet, the name of which derives prosaically from an Old Norse word meaning “wave”—is really an echo of this enraged pig storming in from the Irish Sea.

Boar were similarly venerated by the incoming Anglo-Saxons; Beowulf, in their own national epic, went into battle with a boar’s-head standard, and boar were frequently used as adornments on helmets. The popular Anglo-Saxon names Eoforheard, “Boar-hard,” and Eoformund, “Boar-protector,” testify to their ubiquitousness, and boar mythology also permeates much of mainland Europe. The ancient Celts charged into battle to the ominous bellow of the carnyx, a huge bronze trumpet shaped like a boar’s head, and the swine god Moccus was a god of fertility (the name is echoed in the modern Welsh word for pig, mochyn). The legends of Scandinavia, Germany, and particularly Greece teem with swine: the fourth labor of Heracles was to capture the Erymanthian Boar, which he then hurled into the sea; Theseus slayed the Crommyonian Sow; and bloodthirsty heroes from far and wide participated in the ritual hunting of the great Calydonian Boar. In ancient Greek culture, these nocturnal foragers, emerging with the shadows of dusk, symbolized darkness, winter, and death.

But as Moccus, a god of fertility, shows us, death means life as well.

As often happens, I only see them once I have stopped looking for them. After hours sitting watchfully away from the busier walking trails, I am tramping through the open forest, thinking about other things, when a quiet parade appears—my first sounder. The group is moving eastward through the trees, not going through the deep, dark woods but along a sunlit path, and to my delight, I see the pale dun of boarlets, affectionately nicknamed “humbugs” for their stripy backs. The formation has sound military sense—one adult in front, five or six boarlets, another adult, three more boarlets, and two adults bringing up the rear—a convoy providing safe escort through enemy territory.

According to Friends of the Boar, a group that campaigns for their reintroduction not just to the Forest of Dean but throughout the UK, tabloids have frequently put out stories saying that sows give birth three times a year to up to twelve boarlets each time, stoking ancient, perennial fears of incomers overbreeding. In truth, they’re not as prolific as that—sows in the forest will normally have between five and seven a year—but it’s undeniable that their birth rate is impressive. The forest ranger said that the original escapees were not “pure” wild stock from Europe but hybrids bred for fertility; that, coupled with the fact that boar can freely interbreed with feral and domestic pigs, explains why the forest’s population has exploded in recent years.

The sounder vanishes, reappears, trotting silently and purposefully, now highlighted by spots of sun, then merging into shadow. The lead hog takes a swift right turn down a steep, brambled bank and the troop follows dutifully; within seconds they are gone. Their perfect hoofprints in the mud are trackable for a while, and then these signs are gone as well. I wish the little boarlets luck when guns come for their parents.

Later that day, the Gloucestershire Way—a long-distance walking trail that partly follows Offa’s Dyke along the border with Wales—leads me to the Speech House, on the road to Cinderford. Originally Charles II’s hunting lodge, this three-story redbrick building came to host the Court of the Speech, a local parliament serving the interests of freeminers and verderers: officials protecting the forest’s vert and venison (vegetation and wild game) and handing out traditional rights of foraging and pasture. In 1688 the building was ransacked by Foresters protesting enclosure—the fencing-off of the woods for plantations, which the dispossessed commoners saw as the land grab it was—but the court of the Verderers continued, as it does today. Four verderers, elected for life, still meet here four times a year to oversee forest management, although the real power now lies with government departments. The target level of four hundred boar has been discussed within these walls, but it is the Forestry Commission that does the actual shooting. What strikes me about the cull, however, is that no one is suggesting eradicating boar altogether, as they are in parts of the world where feral pigs are non-native. Under international law, the UK government is obliged to consider any species returning from extirpation as native rather than invasive, so the boar have the de facto right to remain. They are here to stay—but humans decide how many.

The Speech House is closed because of the pandemic, and with its curtained windows and fastened doors, it has the vague appearance of a building under siege: a feudal manor, lording it over the common creatures of the forest. The turf, most conspicuously, is rooted right up to its walls. I like to think the rioting peasants might have approved.

They are creatures trying to stay alive. They have been here as long as we have. They are difficult, as boar should be. That’s what “wild” means.

Near one of the forest’s lakes, there is a secret, shaded place where rotting trunks thrust from the moss and small streams bubble through ferns. It feels primordial, the close-packed firs creating a sense of privacy and concealment. Stumbling here by accident, I find myself in a sanctuary that has been terraformed by boar, with wallows under upturned root plates and meandering, trampled paths, where the bases of the trees are thick with back-scratched mud. Behind a fallen trunk is a sight that might be familiar in Romania, Java, or Japan—or anywhere in the boars’ native range, which wraps itself around the world: the dark shape of a sow with a row of boarlets suckling, an image that resembles something from ancient cave art. It feels like a hidden kingdom, a place I should not have found, and I quickly go on my way. Two people pass on a nearby path, laughing and gossiping, oblivious of how close they are to a mother suckling her young, and I lurk in the undergrowth to watch them as they pass, seeing those humans for just a moment—so loud and free, so confident—as a wary boar might see them, peering from the darkness.

I have a personal, if abstract, connection with boar, one that has fascinated me since childhood. A branch of the Scottish side of my family were Crookshanks, whose name derived from the “shank” (hill) near Cruick Water in Aberdeenshire, and their crest depicts three black boars’ heads on a yellow field. I don’t know what they symbolize, but these martial animals have always been admired for their bravery, strength, and stubbornness, even as they are disparaged for their coarse, uncivilized ways. Respected and hated, praised and cursed—boar seem to represent extremes, from fecundity to death. The controversy of their reintroduction echoes an ancient duality: Are today’s boar more like Moccus, bringing new life from the soil and regenerating ecosystems, or are they modern manifestations of the terrible Twrch Trwyth?

The truth, fittingly for boar, lies somewhere in between: at the edges, in the dusks and twilights, the gray area in the middle of things. The descendants of the escapees that first broke free, or were released, are not paragons of ecology, miraculously restoring forests to a state of primeval purity. Nor are they vandals, mindlessly destroying. These values that we place on them say more about us than about them. They are creatures trying to stay alive. They have been here as long as we have. They are difficult, as boar should be. That’s what “wild” means.

A last evening walk behind the cottage, in the steep part of the woods, where the dense trees end suddenly in fields and solar farms. I follow the path of boar through pines, startling three muntjac deer, who crash away, unnerving me; and just as my nerves are settling—that sudden, familiar presence. The black back legs, the profiled haunch, and then it lumbers into view: no boarlet or juvenile, but the biggest boar I’ve seen. It lets out a warning roar and thumps its hooves upon the earth, a vibration I can almost feel, before it turns its back on me. The message is clear: You don’t belong here. Not at night. This is my world. Respectfully I back away and leave it to the shadows.