Stephanie Krzywonos is a Xicana nonfiction writer. Her forthcoming debut book is Ice Folx, an intersectional memoir set in the Antarctic underworld. She has written about her experiences on “the Ice” for Sierra Magazine, Ofrenda Magazine, The Willowherb Review, Kosmos Journal, The Dark Mountain Project, The Behemoth, and The Antarctic Sun.

Studio Airport, founded by Bram Broerse and Maurits Wouters, is an interdisciplinary design studio that ventures out into the cultural ether to forage for anomalies, creating work that spans art, culture, science, and ecology. In addition to Emergence Magazine, their creative partners include the Design Museum, See All This Art Magazine, Slowness, Normal Phenomena of Life, and Sapiens Magazine. They serve as master tutors at the Design Academy Eindhoven and were recognized as European Agency of the Year 2024 by the EDA.

From ochre to lapis lazuli, Stephanie Krzywonos opens a door into the entangled histories of our most iconic pigments, revealing how colors hold stories of both lightness and darkness.

“If one could only catch that true color of nature.

The very thought of it drives me mad.”

—Andrew Wyeth

Prehistoric cave painting, Grotte de Font-de-Gaume

Courtesy of Olivier Huard

OCHRE

Darkness filled Font-de-Gaume cave. But dark is not the same as the color black. Dark means little or no light. Black isn’t an absence, but a presence.

Font-de-Gaume contains the only polychromatic prehistoric cave art still open to the public. Lascaux, fourteen miles away, closed to visitors in 1963: the carbon dioxide and humidity from human sweat and breath was damaging the paintings. Outside the cave in daylight, large beige-grey marbled cliffs overhung the habitable cottages of Les Eyzies-de-Tayac and the ruins of human shelters around 40,000 years old. Here, in 1868, a geologist uncovered the bones of five Cro-Magnon skeletons, which, at the time, were the earliest known examples of Homo sapiens sapiens—us. Homo sapiens, in Latin, means the wise human. Inside the cave, 250 earth-colored images of reindeer, bison, woolly mammoths, ibexes, horses, and a wolf haunted the walls. Most of the animals were outlined in thick black lines and filled in with rich, earthy ochre paint.

Pigment, a form of nature, is an insoluble substance that gives color to paint and other materials. The melanin in hair, skin, and eyes is a pigment, so is the chlorophyll in plants. Ochre—found decorating 350,000-year-old paleolithic bones—is the oldest colored pigment used by humans. In 2008, archaeologists discovered a 100,000-year-old painting kit in a cave in South Africa which included ochre pigments, an abalone shell used as a palette, a stone for grinding, and bone spatulas for mixing and dabbing the paste. Ochre is life in the form of a paste. To make it, gather earth, specifically clay or rock from land rich in mineral oxides. If not already a powder, crush it, then mix with liquid like fish oil, animal fat, blood, or saliva. Ochre’s iron oxides vary in color, from pale yellow to brown and red, but the oldest documented ochre pigment is red. In the languages of the many ancient Aboriginal cultures who used ochre, there is no distinction between ochre’s color and its substance, ancestral land. We still use red ochre in lipstick.

In the cave, our guide, Blaise, told us that experts thought the artist, or artists, intended these paintings for worship, reverence, and ceremony and painted on scaffolding by the flickering light of reindeer fat. Blaise also told us the artists were tall and dark-skinned—we would call them Black. As a so-called “person of color,” this intrigued me.

Our battery-powered light was steady and still as it illuminated a bison placed so precisely that the natural lumpiness of the rock wall made its bulk look real. Blaise asked us to imagine how the movement of the flames would have made the animals look alive, their muscles rippling and quivering on a canvas made of rock. In front of me, a female reindeer kneeled, and a male tenderly licked her forehead. The image was around 16,000 years old. Between 10,000 and 11,000 years ago, as the planet warmed and our last ice age ended, all of the reindeer in these paintings retreated northward with glaciers or were hunted to extinction.

Blaise asked us to stand near a different wall, then turned on a light. An outline of an artist’s hand was inches from my face. The hand seemed to pulse. Maybe it was just my heart pumping blood behind my eyes. The artist had filled his mouth with the same ochre used to color the animals, held up his large left hand, then sprayed ochre paint against the wall. Whose blood, whose spit, whose fat was this? The artist could have been hunting, been doing anything else in sunlight, but chose to enter the dark to paint, to love what is, to record a reindeer kiss forever, or for as long as rock lasts.

These artists didn’t just try to capture what they loved—they left a warning. One motif in prehistoric cave art, Blaise said, was to paint the most dangerous, violent animals in the deepest part of the cave. We were not allowed to travel deeper inside of Earth to see them: Font-de-Gaume, this museum of prehistoric art, was re-discovered in 1901, and already people had destroyed too many paintings. The animals in the very back were a woolly rhinoceros, a lion, and the profile of a human face, on which a tear appears to fall.

Maybe, as reindeer herds dwindled, the artists were expressing their sorrow and regret. Perhaps the face is saying: if we are not wise, our loves can lead down hideous paths.

Bone char made from pyrolyzed animal bones

Courtesy of Scott Bagley

BONE BLACK

In some ways, black, the color of outer space, is the most primordial pigment. The first black pigments we used came from the hearth: scorched wood and animals. Charred bones make an especially rich black. The black lines that give Font-de-Gaume’s reindeer their shapes and structure likely came from the bones of the very animals the images depicted. In 2,650 BC, Egyptians used bone black to paint Perneb’s tomb; Rembrandt, Velázquez, Manet, and Picasso all used it. Renoir confessed: “I’ve been forty years discovering that the queen of all colors was black.” Bone black is 10 to 20% carbon; calcium makes up the rest. To make bone black, remove all fat, muscle, and tendons from the bones and roast in high heat while starving them of oxygen.

Once made by hand by the artists who used this pigment, bone black later became mass produced. By the mid-nineteenth century, Western attitudes toward the animals who were the source of bone black had become extractivist to the extreme. As the near genocide of the North American continent’s estimated sixty million bison was almost complete, companies like Michigan Carbon Works cooked bison skeletons into bone black as pigment, fertilizer, and a purifier and filter for sugar. At one point, it was estimated that only three hundred bison survived. There were various reasons why the bison were slaughtered: one of them was to starve Indigenous peoples into submission.

Settlers in the west were paid to gather and send bison bones back east via the new railroads. One mid-1870s photo shows two men posing, one on top of and one casually leaning against a mountain of 180,000 neatly stacked bison skulls. By the late nineteenth century, Michigan Carbon Works was the largest industry in Detroit. “As buffalo bones on the prairie became scarce, scavengers began to raid Indian Burial Grounds for bones,” their website says. “A great rift was created in the industry and human bones became a source for their arguments. Finally, all human bones were unacceptable for the bone industry.” Bone black is the presence of an absence.

In the 1960s, the Ebonex Corporation bought the bone black division of Michigan Carbon Works. “Bones no longer come from the prairies, but tradition is upheld when charred animal bones are milled and blended to create bone black pigments,” Ebonex says on its website. “Each grade of pigment is created with pride, and followed with excellent customer service.”

Today, most commercial white sugar is purified using bone char, and you can still buy bone black pigment for your art projects made from cows and pigs. Black paint made from ivory has a higher carbon content, so the depth and intensity of its black is highly prized. To make ivory black, mix ground charred ivory—tusks, teeth—in oil. Ivory black is no longer made commercially because of the expense and near extinction of its sources.

Juglet from an Egyptian tomb, ca. 1750–1640 BC

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Lapis Lazuli, Ultramarine, Egyptian Blue

A richer blue than the ocean, a richer blue than the sky, nuggets of lapis lazuli, a metamorphic rock that Earth creates with high heat and pressure, have been extracted from the Indus Valley—present-day Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India—since the seventh millennium BC. “The deeper the blue becomes,” said Wassily Kandinsky, “the more strongly it calls man towards the infinite, awakening in him a desire for the pure and, finally, for the supernatural.”

In the ancient world, lapis lazuli traveled to China; to Mesopotamia, where it was mentioned in The Epic of Gilgamesh; and to Egypt, where it was crafted into a pharaoh’s funerary mask. Cleopatra famously used powdered lapis lazuli as eye shadow. Egyptians made ḫsbḏ-ỉrjt, an imitation lapis lazuli—the earliest known manufactured pigment—as early as 2,500 BC. They heated limestone, quartz sand, and scraps containing bronze or copper to temperatures of up to 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit with controlled oxygen levels.

But Europeans didn’t lust for “Egyptian blue”—they wanted the real thing. Lapis lazuli entered Europe in the Middle Ages via Venice, and Europeans rebranded it “ultramarine” based on its origins, “beyond the sea.” “Azure” is a misspelling of the medieval Latin word for lapis lazuli. To make ultramarine, grind lapis lazuli into a fine powder; mix it with melted wax, oils, and resin; then knead in a lye solution.

Artists loved to paint the Virgin Mary’s robes ultramarine, and Vermeer tinted the head covering of his Girl with a Pearl Earring with the blue, miring his family in debt. Michelangelo couldn’t afford the pigment.

Red-mouthed dog winkle sea snail

Courtesy of Ryan Hodnett

Tyrian Purple, Mauve

According to the ancient Phoenicians, a dog chewed a mollusk along the coast of Tyre, a city in Lebanon, its tongue turned bright purple, and its human owners noticed. Also called Phoenician red, Phoenician purple, imperial purple, and royal purple, Tyrian purple was the most rare and expensive pigment in human history and is at least four thousand years old. Amazingly, weathering and sunlight makes this purple brighter.

To make one ounce of Tyrian purple pigment, harvest the hypobranchial gland mucus of 250,000 predatory murex sea snails. To do this, some say boil them for days, some say crush the snails and let them bake in the sun, and some say ferment their liquids in vats of urine. Before colonization, ancient Mexicans also created this purple from snails they called tixinda, but they learned how to milk the mucus from the snails and return the creatures safely to the Pacific, where the population has since been decimated by poachers and climate change. Gastropods, which include slugs and snails, have lived on Earth for about five hundred million years, about 499.7 million years longer than Homo sapiens sapiens.

The few remaining snail dyers—only nineteen Mixtec people legally permitted to do so as of 2011—harvest once every moon cycle between October and March. They scamper along the Oaxacan coast carrying skeins of cotton, and when they find a tixinda, they activate its mucus, a narcotic meant for paralyzing prey, by making the endangered snail afraid. The precious few yellow drops drip onto the skein, oxidizing into green, then violet, then a brilliant purple.

Because of its expense and rarity, purple is the color of royalty. By the fourth century AD, only the Roman Emperor was allowed to wear Tyrian purple. Leonardo da Vinci is said to have preferred meditating in a lavender-colored glow.

In 1856, an eighteen-year-old chemistry student William Henry Perkin, who had wanted to become a musician or an artist though his father wanted him to be an architect, was attempting to make quinine for malaria treatment at home over Easter break when he accidentally created a dye he named mauve. Mauve, democratized purple for the masses, became a fashion craze.

On the Internet, you can buy one genuine snail-sourced ounce of Tyrian purple pigment for $115,098.97, plus tax.

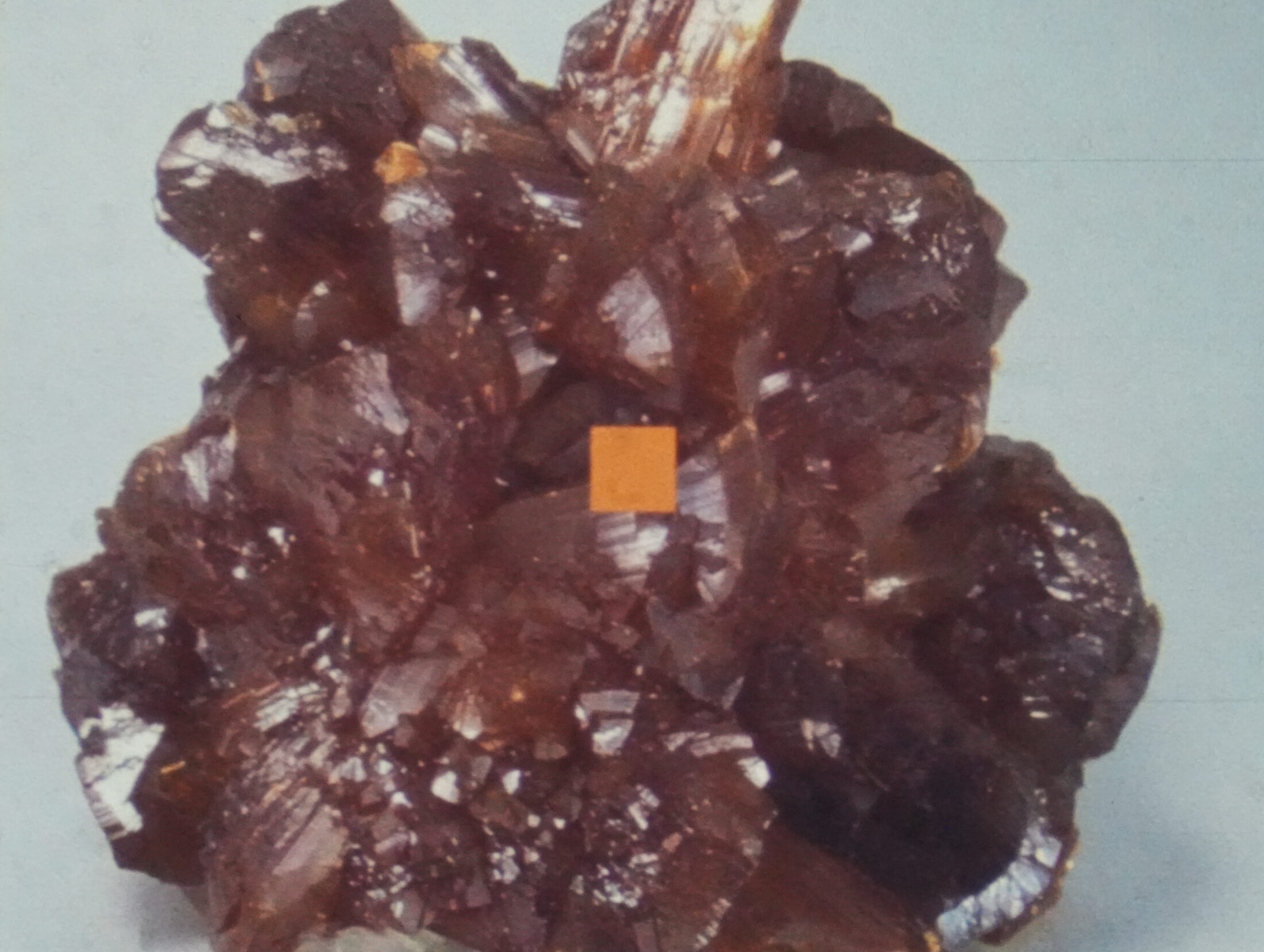

Cerussite, a lead carbonate mineral

Courtesy of Rob Lavinsky

Venetian Ceruse, Bianco Di San Giovanni, Zinc White

Queen Elizabeth I permitted only the inner circle of the royal family to wear purple. She was also rumored to have whitened her skin and hidden her smallpox scars with white makeup made from vinegar mixed with Venetian ceruse. The main ingredient in Venetian ceruse is poisonous lead.

“Nature absolutely paints like the harlot,” wrote Herman Melville in Moby Dick’s famous chapter “The Whiteness of the Whale.” “In many natural objects, whiteness refiningly enhances beauty, as if imparting some special virtue of its own;” Melville wrote, “various nations have in some way recognized a certain royal pre-eminence in this hue; … this pre-eminence … applies to the human race itself, giving the white man ideal mastership over every dusky tribe.”

Most likely, the first written mention of Whiteness as a racial category was in Thomas Middleton’s 1613 play The Triumphs of Truth: “I see amazement set upon the faces,” says an African king to his English audience, “Of these white people, wond’rings and strange gazes.”

In 1694, slave-ship captain Thomas Phillips journaled: “I can’t think there is any intrinsick value in one colour more than another, nor that white is better than black, only we think it so because we are so.”

White, like black, is not a color per se; artists still desired and required white pigments for their work. The oldest white pigments, which were used by Paleolithic artists, came from sources like fossilized limestone and crushed seashells. To make Bianco di San Giovanni white pigment, which was used in Italian frescoes, dry powdered lime, immerse in water for eight days (change the water every day), then shape into small cakes and leave to dry in the sun. In 1978, the United States banned the production of lead white paint, which had dominated the white paint market through the beginning of that century. In 1782, an alternative, zinc white, was invented, but it was unfortunately brittle and tended to crack.

Viva Magenta, Opaque Couché

Aristotle believed God sent colors through celestial rays, that all colors came from black and white and related to the four primal elements: earth, air, fire, and water. In Chinese philosophy, basic colors—black, red, white, yellow, and qing, which is a combination of blue and green—also corresponded to the five elements: water, fire, metal, earth, and wood. In his 1704 book Opticks, Sir Isaac Newton documented that light was made of seven visible colors: red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, and violet. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, author of Faust, asserted in his book, Theory of Colors, that colors could not just be measured scientifically, but subjectively, through the emotions: “Colors are light’s suffering and joy.” In 1814, Patrick Syme published Werner’s Nomenclature of Colours as a standardized field guide for naturalists to accurately name and catalog the colors of the flora and fauna they encountered, claimed, and collected. Thus, in the west, color was officially taxonomized. “Celindine Green is composed of verdigris green and ash grey,” whereas, “Verdigris Green is composed of emerald green, much Berlin blue, and a little white.” Charles Darwin used Werner’s Nomenclature of Colours on his HMS Beagle voyages, and Edward Parry used it in the Arctic as he attempted to discover the Northwest Passage. Before the White men of the doomed Terra Nova Expedition left for Antarctica in 1910, J. W. Lovibond, who created the Lovibond Colour Scale, measured their skin, hair, and eye color. “I believe the purpose of the tests were to see whether men of special colourings were more adventurous than their fellows,” wrote Lovibond’s great-granddaughter.1 The same year, in his essay “The Souls of White Folk,” W. E. B. Du Bois wrote: “This assumption that of all the hues of God whiteness alone is inherently and obviously better than brownness and tan leads to curious acts.” The Nazi Primer, which was given to German teenagers and translated into English in 1938, reads: “For it is all too apparent that the ‘red skin,’ the yellow, the black, and the white are very different. Moreover, within the family of white men all people are not the same. Every attentive observer can recognize distinctions in physical size and shape. The coloring of the eyes, the hair and skin is also very different.”

In the digital age, the Pantone Color System sets the standard for matching and labeling colors. The Pantone Color Institute™ “forecasts global color trends and advises companies on color in brand identity and product development.” Each year, Pantone releases its Color of the Year. “In this age of technology, we look to draw inspiration from nature and what is real,” Pantone said in its press release for 2023’s winner, Viva Magenta, PANTONE 18-1750. “Inspired by the red of cochineal” and “rooted in the primordial, PANTONE 18-1750 Viva Magenta reconnects us to original matter. Invoking the forces of nature, PANTONE 18-1750 Viva Magenta galvanizes our spirit, helping us to build our inner strength.” In Pantone’s online store, you can buy an official Viva Magenta limited edition coffee mug for $30, plus tax: “Audacious, full of wit, and inclusive of all, PANTONE 18-1750 Viva Magenta welcomes anyone and everyone with the same verve for life and a rebellious spirit.”

In 2012, the Australian government hired a marketing firm to find the least appealing color possible to use on cigarette packs; they selected PANTONE 448 C, also called opaque couché. The government described it as an “olive green” until the Australian Olive Association protested; they then referred to it as “dark drab brown.” Pantone, in defense, described it as having “deep, rich earth tones.” Some call PANTONE 448 C the “ugliest color in the world.” A few find it elegant.

Macrophotograph of cochineal insects

Wikimedia Commons

Cinnabar, Cochineal, Dragon’s Blood

In addition to ochre, paleolithic artists thirty thousand years ago in modern-day Spain and France used cinnabar, a mineral linked to fresh volcanic activity and hot springs, as bright red pigment in cave paintings. Romans used cinnabar widely, the Olmecs used it for cosmetics, and the ancient Chinese used it for lacquerware. Cinnabar is mercury sulfide, and highly toxic. To make cinnabar pixels on a computer screen, also called #E34234, mix 89% red, 25.9% green, and 20.4% blue.

Centuries before Hernán Cortés ravaged what is now Mexico, grey nocheztli insects, who would later be called cochinilla by the Spanish and Dactylopius coccus by scientists, gathered in bunches on cacti, especially nopal, drinking sap. The Spanish discovered that Indigenous Mexicans used these insects to dye fabric a far more brilliant red than anything they’d seen before. Ancient Romans used dragon’s blood pigment, harvesting it from a dragon’s blood tree, which when cut, looks like it is bleeding. Nocheztli blood is a redder red because their bodily juices are rich in carminic acid; if you squeeze one until it bursts, its crimson liquid will stain your hands. “Magenta—Aztec,” Frida Kahlo scribbled in her notebook, “old blood of prickly pear, the most alive and ancient.”

Cochineal comes in vibrant reddish hues, like scarlet, crimson, carmine, and orange, and is known for its luster and longevity. To make cochineal pigment, brush plump, wingless females that have just made a waxy cocoon into bags and kill them by immersion in scalding water; exposure to steam, sunlight, or the heat of an oven; or rolling them on a wooden board without popping. If needed, leave their bodies to dry in the sun, then pulverize the dead bugs, and combine the powder with liquid. Seventy thousand female nocheztli make one pound of cochineal; harvesting the insects is tedious.

In 1578, the Spanish shipped seventy-two tons of cochineal, more profitable than gold, from Peru to Spain, which equals about ten billion female nocheztli. Pirates attacked Spanish ships for this red, and the Spanish introduced cochineal production to the Canary Islands, which became a major exporter of the pigment. At the same time and on the same waters, the transatlantic slave trade was well underway, which kidnapped nearly thirteen million people between 1501 and 1867.

Cochineal was primarily used for fabric: gowns, robes, the upholstery of Versailles, and British officers’ uniforms. Many Renaissance and Enlightenment-era artists painted with cochineal. Edvard Munch claimed that his painting The Scream, which was first titled The Scream of Nature, was inspired by a blood-red sunset. “I sensed a scream passing through nature; it seemed to me that I heard the scream. I painted this picture, painted the clouds as actual blood. The color shrieked.”

Marketers don’t want so much to capture the shriek of animals who give products their hue, but rather to capture the attention and appetites of consumers. Red insect pigment, also known as E-120 or Natural Red 4, is still used to color drinks, food, and makeup, especially those branded as having “natural ingredients.” In 2012, Starbucks stopped using cochineal in drinks such as its Strawberries & Crème Frappuccino after consumers protested.

Mummy Brown

In the sixteenth century, artists began to paint with the color of the dead: mummy brown, the color of soil and shit. “Recall that whatever lofty things you might accomplish today, you will do them only because you first ate something that grew out of dirt,” wrote Barbara Kingsolver. Bitumen, a resinous mixture of hydrocarbons that sometimes oozed from the ground, had become a popular remedy thanks to the ancient Greeks who believed it had medicinal properties. The Persian word for bitumen is mumiya. People thought the black substance encrusting mummies made a good substitute for bitumen, so when it became increasingly rare in the Middle Ages, exporting mummies to Europe became big business. Europeans not only ate, drank, and rubbed themselves with the powdered ancient bodies, they painted with mummies too.

Mummy brown’s rich, warm hues ranged from reddish to yellowish and even to “Mummy violet.” Mummy brown’s ethereal transparency makes it good for glazing, shadowing, layering, and tinting. “I can paint you the skin of Venus with mud,” said French artist Eugene Delacroix. His 1830 painting Liberty Leading the People, featuring a topless woman brandishing a French flag while leading revolutionaries, got its je ne sais quoi from mummy brown. To make mummy brown, grind up carefully preserved human or feline bodies and mix with myrrh and white pitch.

When supplies of authentic mummies dwindled, the corpses of slaves, criminals, and the recently deceased were substituted. They were treated with bitumen and left to dry in the sun, much like the nocheztli, then sold as genuine mummies. When the English artist Edward Burne-Jones discovered the origin of his tube of brown paint, he ceremonially interred it in his garden, and one of his daughters planted a daisy on top of it. The French artist Martin Drölling, however, used the corpses of French kings from Saint-Denis in Paris for the rich umber tones in compositions.

By the twentieth century, the supply and demand for mummy brown waned. You can now buy fake mummy brown pigment made from kaolin clay, quartz, hematite, and goethite, and artists-for-hire are available to mix a loved one’s cremated remains—“cremains”—with oil paint and apply the pigment to a canvas.

Prussian blue pigment

Prussian Blue, Reckett’s Blue, Klein Blue, YInMn Blue, Cobalt

In a 2015 online survey of 10,868 adults across ten countries and four continents, blue was overwhelmingly people’s favorite color. Aside from coloring water and sky, blue is the rarest color in the natural world. In 1704, German chemist Heinrich Diesbach accidentally discovered the first modern synthetic pigment: Prussian blue. Diesbach thought he had found what the Egyptians called ḫsbḏ-ỉrjt: the original color of the sky. Prussian blue replaced the ultramarine made from lapis lazuli. This more affordable blue colored The Great Wave off Kanagawa by Katsushika Hokusai and saturated Pablo Picasso’s blue period.

According to some color psychologists, blue is a color of coolness, calmness, sadness. “Dream, when you’re feeling blue,” crooned Ella Fitzgerald, “Dream, that’s the thing to do.” Prussian blue, chemically known as Fe4[Fe(CN)6]3 is an antidote for radiation and heavy metal poisoning; mixed with sulfuric acid, it also makes cyanide.

In 1826, a French chemist named Jean-Baptiste Guiment heated China clay, soda, quartz, charcoal, and sulfur to make a pigment called French ultramarine, an even cheaper blue, though it lacked lapis lazuli’s depth. In England, this synthetic blue was called Reckitt’s blue and used in laundry to offset yellowing and make whites pop. The British brought the blue to their colonial outposts, like Curaçao in the Caribbean, and imposed their ideas of cleanliness. The locals painted their bodies with Reckitt’s blue as protection from the evil eye.

In 1960, the French painter Yves Klein registered International Klein Blue, IKB, with the French government. When mixed with a specific synthetic resin, Klein considered the pigment “the most perfect possible expression of blue,” which isn’t “the pallid tint of the daytime sky. It is the dark, electric blue of the Paris sky at nine o’clock on a summer night when the energy of the vanished day still resonates through the atmosphere, and the headlights of the traffic seem like sparks descending from above.” At Klein’s direction, nude women covered their bodies in his blue, then painted canvases with their bodies by walking, rolling, sprawling, and dragging each other by the arms as a live orchestra played and watched in the background. He called the series Anthropometries. In 2008, Klein’s monochrome blue painting Archisponge (RE 11) sold for $21,400,500. For $100, you can now paint eighty-five square feet of your home, or whatever or whoever you want, in Klein blue.

In 2009, while working on materials for electronics, an Oregon State University research team led by Dr. Mas Subramanian created YInMn Blue, made from yttrium, indium, and manganese oxides, and claimed it was the first new inorganic blue pigment created in two hundred years, the last one being cobalt in 1802. More vivid than Prussian blue, 1.7 ounces of YInMn Blue powder costs $295, plus tax.

Roman coin with patina

Verdigris, Scheele’s Green

“Green, how I want you green,” poemed Federico García Lorca about the color of life and fertility, “green wind, green branches.” Until the late-1800s, verdigris was the most vibrant green pigment available to artists. The name is Old French for “green of Greece.” The bluish-green copper-based pigment is poisonous, unstable, and forms the patina on the Statue of Liberty. The Flemish painter Jan Van Eyck somehow managed to make verdigris stable and painted the dress of the very pregnant merchant’s wife in The Arnolfini Portrait a stunning shade of green.

To make verdigris, as they did during the Middle Ages or Renaissance, hang a copper plate over boiling vinegar and collect the crust. Mix with a binding agent, like linseed oil or egg whites. “Verdigris with aloes, or gall or turmeric makes a fine green and so it does with saffron or burnt orpiment,” wrote Leonardo da Vinci, “but I doubt whether in a short time they will not turn black.” To make a bright blue antique verdigris patina cheaply in the Anthropocene, one recipe I found via Pinterest instructs: mix three tablespoons of red wine vinegar with one tablespoon of Miracle Grow™ and soak copper for thirty minutes, then let it dry completely.

Invented by a chemist in 1775, Scheele’s green, a brilliant emerald, supplanted verdigris, but its arsenic made it toxic and carcinogenic. Napoleon, who loved gardens, had green, his favorite color, wallpapered into his bedroom in exile. He complained that his British prison guards were poisoning him. The fleur-de-lis pattern of the wallpaper showed traces of Scheele’s green, and Napoleon’s postmortem hair samples reveal substantial amounts of arsenic.

The colors of nature that humankind captured, commercialized, and sold weren’t just displayed in paintings and finery—“colored” people were displayed in museums and zoos, too. In 1815, the same year Napoleon began his exile, Sarah Baartman died in Paris. Baartman, who was also called the “Hottentot Venus,” was a Khoekhoe woman from South Africa who was enslaved and put on display in London just after the British slave trade was abolished in 1807. Baartman was a victim of the “human curiosities” movement that also included exhibitions of “Negro villages” and Indigenous people at world fairs. In the United States, Ota Benga, a Mbuti pygmy man from Congo was displayed at the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1904, moved to a spare room at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, and later housed in a cage with monkeys at the Bronx Zoo until enough people protested. After Baartman died, her skeleton and pickled genitals were on display in Paris’s Museum of Man until 1974. At the request of Nelson Mandela, Baartman’s remains were buried in South Africa in 2002.

Orpiment, an arsenic sulfide mineral

Orpiment, Purree

A sulfide of arsenic, orpiment is a rare mineral. Glowy and with a bright canary hue, ancients and medievals used orpiment to imitate gold. You can find it in hydrothermal veins, hot springs, and much of the orpiment in Italian painting came from the fumaroles of Mount Vesuvius. The Post-Impressionist Paul Cézanne, who used orpiment, complained: “I lack the magnificent richness of color that animates nature.”

You can still buy orpiment; 100 grams of powder costs seventy bucks. It is perfect for use in glazes to render the sunlight, says masterpigments.com, but “due to its toxicity, Orpiment requires careful handling to avoid any contact with the skin.” Orpiment was used as poison for arrow tips and in Chinese medicine. Despite the risks, orpiment’s beauty won out: traces of the pigment have been found in Pharaoh Tutankhamun’s tomb and on the Taj Mahal.

Ochre can sometimes be yellow, but it is not bright. In fifteenth-century India, people began feeding cows mango leaves and collected their urine from special sand. The dried urine was then ground to make a pigment called purree. Van Gogh used this luminous yellow for his swirling celestial bodies in Starry Night. A diet of mango leaves makes cows unhealthy, so by the early twentieth century, the practice of making purree was supposedly banned.

The English painter J. M. W. Turner, known for turbulent and violent marine paintings, used purree so much his critics said his paintings were “afflicted with jaundice.” Turner switched to a synthetic lead-based yellow known to cause delirium. Nicknamed “the painter of light,” Turner also had a passion for black. “If I could find anything blacker than black, I’d use it,” he said.

Vantablack, The World’s Pinkest Pink

Science teaches us that we see white when light hits an object that scatters all the colored wavelengths; we see black when an object absorbs all light, all wavelengths. Just like in the paintings of Font-de-Gaume, black holds all the colors.

The darkest human-made substance is not technically a pigment, but an alignment of carbon nanotubes that absorb 99.965% of all visible light. Developed by Surrey NanoSystems for aerospace engineering applications, Vantablack was unveiled for the first time in 2014. The “Vanta” in Vantablack is short for “vertically aligned nanotube arrays.” When light enters a Vantablack coating, a color so dark it makes three-dimensional objects look two-dimensional, light bounces around the tubes, exhausting itself, trapped, basically forever. “There’s something about black,” said Georgia O’Keeffe, “you feel hidden away in it.”

To make Vantablack, grow a forest of vertical carbon nanotubes on a metal surface. You cannot buy Vantablack because it is too expensive to make, and also it is not for sale. In 2016, after experimenting with the Vantablack, the British artist Anish Kapoor, known for Cloud Gate, the giant bean-shaped mirror in Chicago’s Millennium Park, negotiated with Surrey NanoSystems for exclusive rights to use Vantablack as an art material. Christian Furr, who, at twenty-eight, was the youngest artist to paint a portrait of Queen Elizabeth II, said, “All the best artists have had a thing for pure black—Turner, Manet, Goya.… This black is like dynamite in the art world. We should be able to use it. It isn’t right that it belongs to one man.” Other colors are trademarked: Coca-Cola’s red, Mattel’s pink, T-Mobile’s magenta, Home Depot’s orange, Tiffany & Co.’s blue.

In response to Kapoor’s artistic monopoly on Vantablack, Stuart Semple, a British artist, invented what he hoped was the pinkest pink, and titled it The World’s Pinkest Pink. In 2018, scientists found the oldest pigment on Earth: five-hundred-million-year-old cyanobacteria fossils buried in 1.1-billion-year-old rocks deep below the Sahara Desert were bright pink. The world’s oldest pink isn’t for sale, but you can buy 50g of The World’s Pinkest Pink pigment for $9.99, tax included, unless you are Anish Kapoor. Semple’s website reads:

*Note: By adding this product to your cart you confirm that you are not Anish Kapoor, you are in no way affiliated to Anish Kapoor, you are not purchasing this item on behalf of Anish Kapoor or an associate of Anish Kapoor. To the best of your knowledge, information and belief this paint will not make its way into the hands of Anish Kapoor. #ShareTheBlack

Kapoor, who was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II, obtained the pink anyway, and posted a photo of his middle finger dipped in the powder on Instagram.

In a 2021 interview during his Oxford-based art show, which featured red and gory sculptures of disemboweling, decapitation, bloodletting, and the vagina of a ten-thousand-breasted woman, Kapoor mentions that the first cultural act of solidarity may have been ancient women whose cycles synced up and who covered their bodies in red ochre to hide their menstrual blood. When he experienced a nervous breakdown as a young man, his mother flew to India to retrieve some earth from the place he grew up. Kapoor placed it in the darkness under his bed. After that, he dreamed himself well. “Colour is deeply illusionistic,” Kapoor said. “Color is my day-long obsession, joy and torment,” said Claude Monet.

It was during a near-death experience from an unknown nut allergy, during which he said goodbye to his mother, that Semple realized, if he should survive, he should “really become an artist.” Semple, who is White, also sells the world’s glitteriest glitter, VIVA MEH-GENTA (his inexpensive off-brand response to Pantone’s 2023 Color of the Year, which he bans Pantone employees from obtaining), and Black 3.0, which absorbs 99% of visible light. Semple’s product page screams: “HE MADE IT BECAUSE ANISH KAPOOR WON’T SHARE HIS BLACK WITH ANYONE ELSE.” Five ounces of Semple’s Black 3.0 costs a modest $39.99. In 2024, Stuart Semple legally changed his name to Anish Kapoor.

“Whoever fights monsters should see to it that in the process he does not become a monster,” wrote Friedrich Nietzsche in Beyond Good and Evil: “And if you gaze long enough into the abyss, the abyss will gaze back at you.” In Turin, Nietzsche wrapped his arms around a horse, defending it from being flogged, whispered “Mother, I am stupid” to it, then physically and mentally collapsed. Nietzsche never regained lucidity. When he died, his face, preserved in a death mask, looked tender, less than an ideal Übermensch. Other death masks were made, but the original bronze cast, which was the color of stone, was kept in the Berlin National Gallery until Berlin fell during World War II and it became a casualty of war. The human face in Font-de-Gaume has outlasted Nietzsche’s.

In 2019, MIT researchers Brian Wardle and Kehang Cui published their findings about a new blackest black, which absorbs 99.995% of light. John Mather, an astrophysicist and Nobel laureate who was looking into using this black to “shield a telescope from stray light,” said that earlier versions of nanotube blacks were fragile, but this black was “built to take abuse.” The creators of this black, which remains unnamed, allow any artist to use it. As part of the news release, Wardle and Cui partnered with artist Diemut Strebe in an exhibit called The Redemption of Vanity, which was on display at the New York Stock Exchange. Strebe painted a 16.78-carat yellow diamond, worth about $2 million, with the new blackest black. A description of it reads: “The project explores how material and immaterial value is attached to objects and concepts in reference to luxury, society and to art.” The diamond’s face and many facets now appear like a black void.

- Reproduced with permission of the RGS-IBG, RFS/5. The Royal Geographical Society, where this letter is held, neither solicited Mr. Lovibond to apply his scientific test to the men of Captain Scott’s Antarctic expeditions nor do they endorse his findings.