Katie Holten is a visual artist based in New York City. She grew up in rural Ireland and studied fine art and history of art at the National College of Art and Design in Dublin and the Hochschule der Kunst in Berlin. In 2003, she represented Ireland at the 50th Venice Biennale. In 2015, she created a Tree Alphabet and used it to make the book About Trees. Her latest book is The Language of Trees: A Rewilding of Literature and Landscape.

Artist Katie Holten seeks to decolonize language and rewild the imagination by transforming letters into trees. Combining the ancient script Ogham with Irish and English, her Irish Tree Alphabet transforms words into an arboreal language of place and belonging.

Would you believe me if I told you the Irish Tree Alphabet grew from a seed rooted within James Joyce’s Ulysses? Yes, somehow this modernist text offers a way to re-forest literature and our environmental imaginations. There is an enchanting section in the “Cyclops” episode in which two Irish nationalists lament Ireland’s treeless state: As treeless as Portugal we’ll be soon, says John Wyse, or Heligoland with its one tree if something is not [done] to reafforest the land.

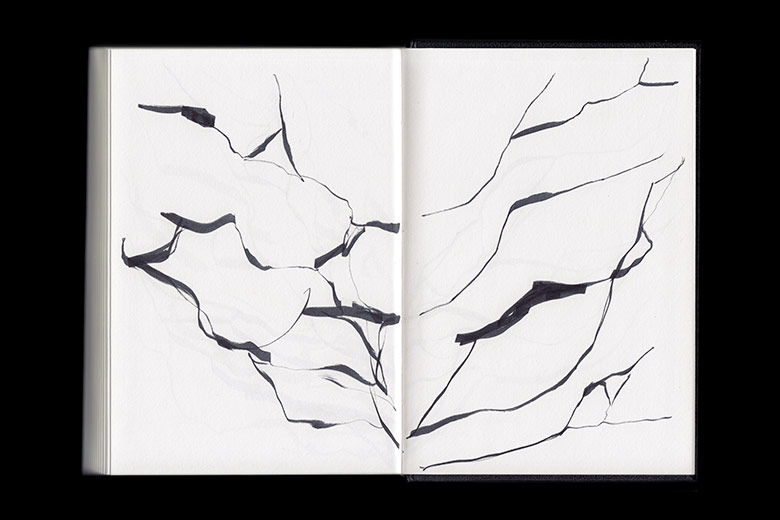

Joyce conjoins sociopolitical history and natural history in a fantastical tree wedding ceremony. Humans and trees entwine and merge to celebrate the marriage of Miss Fir Conifer of Pine Valley and Jean Wyse de Neaulan, grand chief ranger of the Irish National Foresters. The wedding guests are human-tree hybrids. (The confetti—“hazlenuts, beechmast, bayleaves, catkins of willow, ivytod, hollyberries, mistletoe sprigs, and quicken shoots”—inspires the punctuation of my tree alphabets.) This human-tree entwinement offers the possibility for a symbiotic relationship with the land.1 We are both ourselves and the trees.

Ireland has long been represented as a fertile woman with flowing hair: Éire. Forests covered the island after the last Ice Age, but once Mesolithic hunter-gatherers arrived, the hybridization process began. Nature and culture merged, creating new landscapes, chopping her curls. Ireland’s forest ecosystem gradually declined as immigrant Neolithic people cleared land for farming, a process that continued for thousands of years. In the seventeenth century, British imperialists gorged on the island’s oak forests in order to build their battleships.

To this day there is tension between citizens calling for rewilding—a return to native broadleaf forests—and the Irish government, which resists supporting true efforts towards reforestation and instead promotes “tree farms”—sickly, profit-based, conifer plantations.

Trees breathe out. We breathe in. But what happens when there are no trees left?

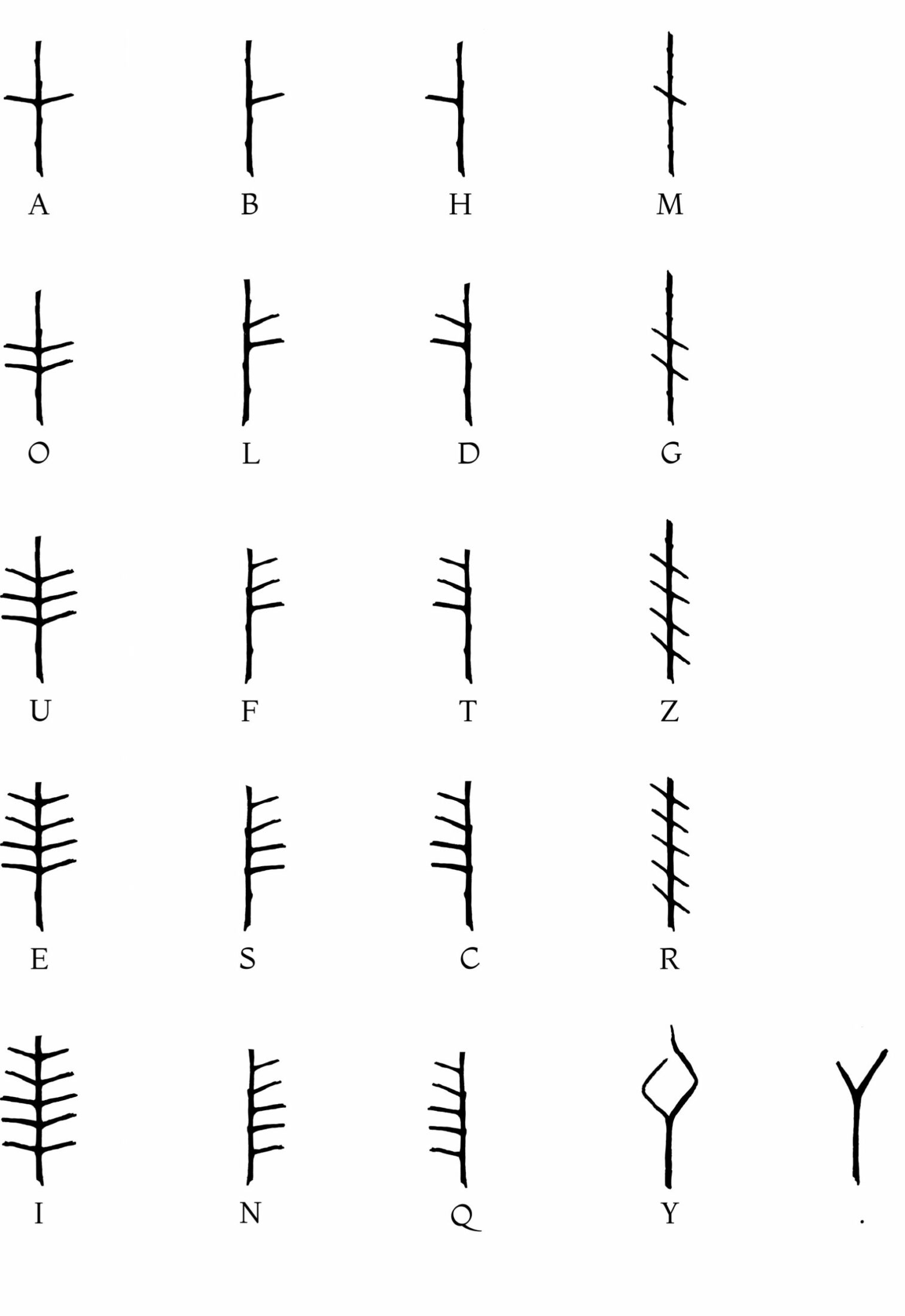

Ogham is Ireland’s earliest form of writing. Dating from the fourth century, it is often affectionately called a tree alphabet. It is an archaic script using trees for letters. In Ogham, the characters were called feda “trees” or nin “forking branches” due to their shape. Astonishingly, this ancient alphabet was “written” from the roots up—each character sprouting from a central line, like leaves on a stem or branches on a tree.

Language as living matter.

Today this early medieval alphabet is an enigma, surviving as inscriptions scratched in stones.2 Any messages that may have been carved on trees no longer remain; although they are not here to share their story, I sense them branching deep in my cellular memory.

I have no memory of being taught Ogham at school.3 I don’t know when it first seeped into my consciousness; it feels like it has always been there. You could say Ogham is my protolanguage, my “ur-alphabet.” It wasn’t until I started drawing Ogham characters this spring that I appreciated how organic it is. Unlike our English, which unfolds left to right and down the page, you read Ogham as you would climb a tree, from the ground up.

Growing up in rural Ireland, I found solace in trees. Trees are truthful.

When I moved to New York City, I was inevitably drawn to street trees. When I created a Tree Museum to celebrate the centennial of the Grand Concourse in the Bronx, I began searching for a tree language or a “forest of tree languages.”

Scientists like Suzanne Simard, Peter Wohlleben, Hope Jahren, and Merlin Sheldrake study the languages of plants. They’ve shown how trees talk to each other using mycorrhizal fungi, an underground hyphal network, affectionately called the wood-wide-web.4 These “natural” languages exist beyond our notion of communication.

Learning about the languages of trees, their social networks, and our own human microbiome forces us to rethink our relationship with “things.” If trees have memories, respond to stress, and communicate, then what can they tell us? Will we listen? Where does one species end and another begin? What happens when we know plants can talk?

Reading and writing are how we compose ourselves and make sense of the world. If translation is the most intimate form of reading, could translating our words into trees be one way to conjoin ourselves with the world around us?

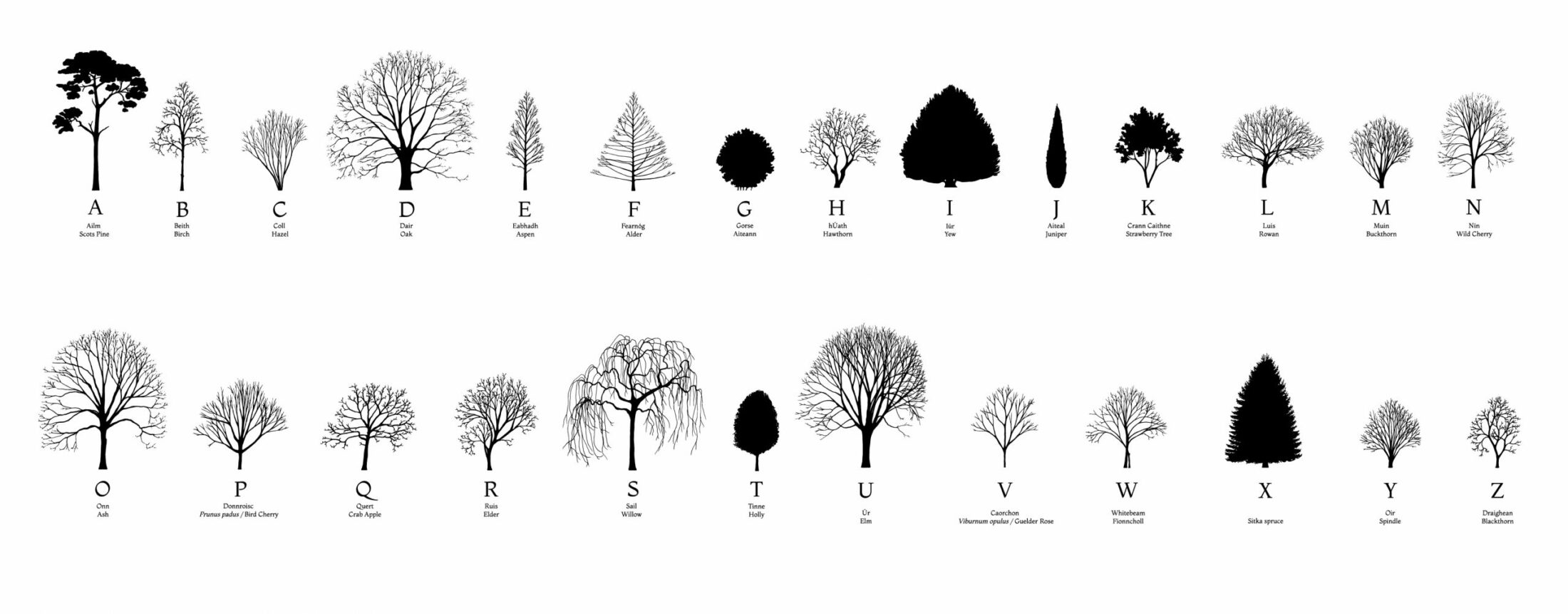

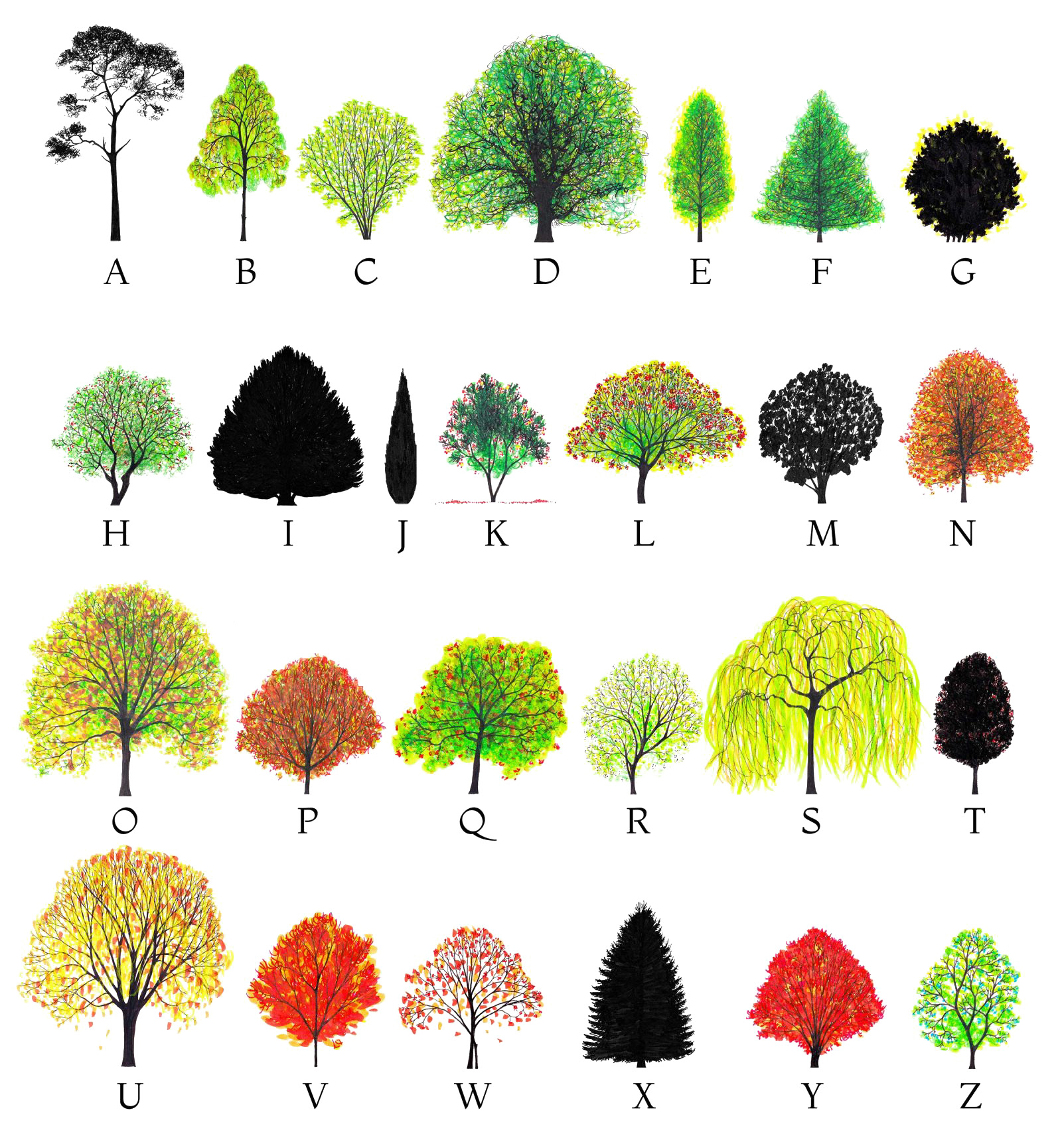

Sensing a crisis of representation as our species sleepwalks deeper into the Anthropocene, I became fascinated with the possibility of drawing a language beyond my native human tongue. So I drew a family of trees, one for each letter of the Latin alphabet, creating a Tree Alphabet and a typeface called Trees.

Why write with Times when you can write with Trees?

Tree wedding ceremony from Ulysses translated into Irish Trees.

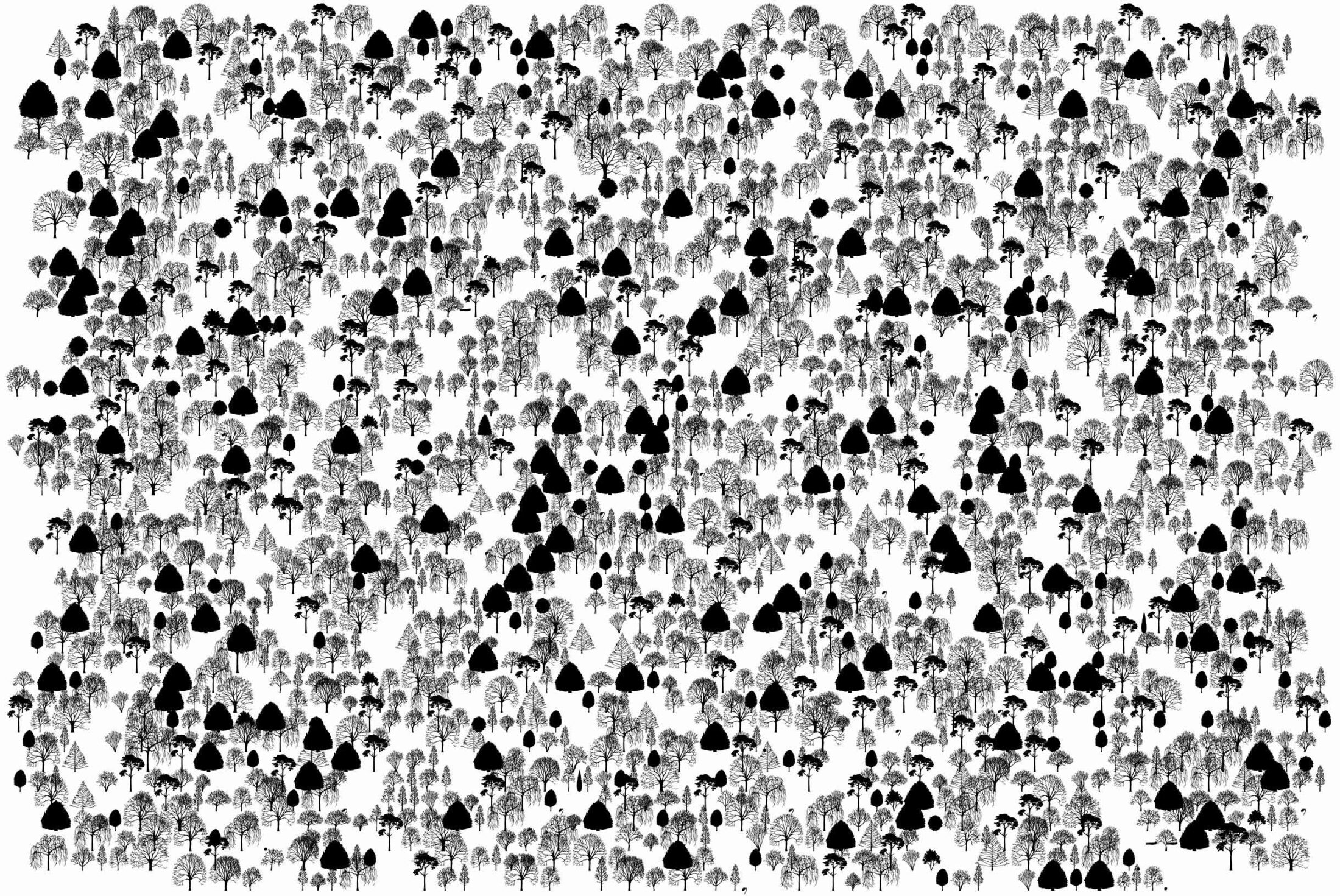

When we translate our words into glyphs (like trees, for example), it forces us to re-read everything. A tree font allows us to play with the molecules of language. New letter forms—Trees—replace each character in the Latin ABC. As we tap, trees sprout on screen. Words may be the smallest units of language, but letters are the tiniest “bits” of our language ecosystem, like individual trees in a forest. A tree ABC helps us re-read the past, re-present the present, and re-imagine the future by offering a simple way to translate what we think we already know.

The Tree Alphabet offers a way to elucidate the paradoxes of the Anthropocene by slowing us down to decipher words in the woods. It is an invitation to start thinking about inter-species communication, multi-species storytelling, and our ancient entwinement with trees.

By transforming a Latin character into a digital Tree, I wondered, can we expand our understanding of knowledge, typography, books, and stories themselves?

Words are the smallest units of language that stand alone. They are central to our experience of being human. The languages we speak profoundly shape the way we think, the way we see the world, and the way we live.

Our capacity to produce language is innate, like a tree’s ability to produce leaves. Buds burst with potential stories. Words create meaning; they are alive and shift with culture. Words can be planted. They matter. We can seed stories, watch them take root, and grow. That’s what makes us human.

We are all matter.

But what is matter, we may ask? The word itself is suggestive of what’s at stake. The etymological roots expose a tension. The Latin materia suggests “timber,” while mãter means “mother” or “source.” So, matter is a hybrid, a woody, fleshy fusion of living tissue with a semiotic heart. The heartwood, if you will.

If language—like everything else—is a direct extension of nature, then it was here before humans.5

Without language fossils, we can’t be certain of the origin of human language or words. The most influential artifacts of our civilization are word mountains, what we call stories or books. Our ancestors shared tales, and some of those reached us as collective narratives, like Genesis and other creation myths. Stories evolve as multiple authors repeat, copy, translate, and circulate them: for example, in the United States, there is the Constitution; in Ireland, the Book of Kells and the Book of Ballymote.6

What exactly is a book? With roots in Old English, boc refers to any piece of writing but is also identical to the word for “beech tree.”

Old English boc “book, writing, written document,” generally referred (despite phonetic difficulties) to Proto-Germanic bōk(ō)-, from bokiz “beech” (source also of German Buch “book” Buche “beech”), the notion being of beechwood tablets on which runes were inscribed; but it may be from the tree itself (people still carve initials in them).

Latin and Sanskrit also have words for “writing” that are based on tree names (“birch” and “ash,” respectively). And compare French livre “book,” from Latin librum, originally “the inner bark of trees.7

It can’t be a coincidence that some of the first forms of writing used trees.

We’re spiraling in toward the Heartwood.

I want to create living alphabets—stories we can plant—to literally make words matter.

My heartwood is in Ireland, so of course, I wanted to make an Irish Tree Alphabet. But it has not been easy. Unlike my previous alphabets, it incorporates not only English but also Irish (which I don’t understand), and Ogham (which no one fully understands).

Irish should be my native tongue, but it’s a foreign language. I am not alone.

In history class we were taught that British landowners took our food, exacerbating a natural famine with their ideology; evicted us from our homes, creating waves of immigrants (despised by Americans at the time); and beat Irish out of us, forcing us to speak English. Our native language was seen as a threat. Like many minority languages, it is more than just a means of communication, it is an integral part of our indigenous consciousness.

Despite efforts to eradicate it, the Irish language survived in hidden “hedge schools,” often held outdoors, that secretly provided education in a time of suppression. Yes! Yet another connection between the Irish language and trees, and another link between the past and the present. During this COVID-19 pandemic, parents and teachers have created their own “hedge” or “forest” schools—bringing children outside to learn under trees.

Translating English—and Irish—into Trees is a way for me to speak to the colonization of our words. Language is never neutral.

Irish is an endangered language, with small clusters of native speakers in Gaeltacht areas in the west of the country, including Donegal, Galway, Kerry, and Cork. It is a language steeped in its native landscape, with thirty-two words for “field,” forty-five for “stones,” and seventy thousand Irish place-names.8 Just imagine how this explosion of words describing the natural world can rewild our imaginations, creating a more magical way of being in the world.

As for Ogham, although it is about 1,700 years old, it continues to evolve. Over the years I have searched for a definitive guide so that I could translate it. But each version I’ve found differs slightly from the others.

We don’t have any way to know what the original marks represent, so everyone is entitled to their own opinion about what they might mean. Once I started drawing, it was satisfying to discover that some of the letter names are unmistakably names of trees. B is Beithe is Birch. C is Coll is Hazel. D is Dair is Oak. O is Onn is Ash. S is Sail is Willow. Others are problematic: we’re not sure of their original sound. NG is possibly GW and Z is possibly ST; but what are their corresponding trees?9

Ogham is a phonetic alphabet created from the sounds of a very early form of Irish, so it’s not easy to translate directly from English.10 It lacks letters like K, P, and W. But languages evolve when people learn to make do and tweak things.

This ancient alphabet is ripe for exploration. It feels alive in my heart. It feels like the right time to excavate the cellular memory.

While I was trying to create a new tree alphabet that combined English, Irish, and Ogham, I realized that I needed to choose a group of twenty-six trees that speak to these different eras, languages, and cultures while remaining coherent enough to be planted in the twenty-first century, during this time of intense climatic chaos.

In my Irish Tree Alphabet, A is for Ailm or Scots Pine. As the name suggests, Scots pine occurs naturally in Scotland. But the species has been native to Ireland since the last Ice Age. We can use the inevitable migration of trees, and the tree alphabets, to reconsider what it means to be native and how even something seen as foreign should be cherished. We are all native to Earth, our one and only home.

Many of the trees that we sit under today are dying. The climate is changing. Native species are being forced to migrate; non-native species move in and take root; others are brought in by humans. The new Irish Tree Alphabet acknowledges the climate emergency by also including “new” trees—like Sitka Spruce, representing the letter X.11

Yesterday I watched as trees planted on peatland in Donegal started sliding away, as if the Earth was shrugging them off and breathing a sigh of relief. The wrong trees in the wrong place.12 Over the last few years, my heart has ached seeing mature trees butchered on the streets of Dublin, ancient hawthorns ripped out near Ardee Bog, and hedgerows all across Ireland massacred.

Because words do matter, and because my heart is bursting for what we are losing, I offer these tree alphabets—new ABC’s—as a way to reforest our imaginations, suggesting a way forward by looking backward through our branches of knowledge.

I invite you to download the free fonts and translate your words into Trees. You could plant them—making your words matter.

It’s also a fruitful and fun way to introduce children (and adults) to the beauty of communicating across time and species. Translating thoughts into Trees lets us share our vulnerabilities in this time of extinction, while offering a simple way to engage with human-induced environmental change.

If 2020 has shown us anything, it’s that we are living, breathing, and writing a whole new story for our species. We need other perspectives, from Beech, to Birch, to Book, to Bog, and back again.

I’m haunted by the ghost of Ireland’s forests. Perhaps one day I’ll translate Ulysses into Trees, reforesting the novel, creating a hybrid, planted, literary landscape.

Perhaps by translating our old myths and stories—what we thought we knew—we can radically rewild our words and learn to see beyond ourselves. The act itself of composing love letters to our future selves might just be what makes our future selves possible. The future is no longer somewhere else. It is here and now. This is our story.

Isn’t it about time that our modern alphabets and our stories embraced other species?13 Why is it taking us so long? Together we can write a new world.

Download the free Irish Tree Alphabet font and translate your words into Trees. http://irishtreealphabet.ie/

- For an eco-critical reading of Ulysses, it has been useful to read “Ecocriticism, Joyce, and the Politics of Trees in the ‘Cyclops’ Episode of Ulysses,” by James Fairhall, EcoJoyce: The Environmental Imagination of James Joyce, eds. Robert Brazeau and Derek Gladwin (Cork, Ireland: Cork University Press, 2014).

- I am indebted to Dr. Nora White for our conversations about her research with the Ogham in 3D Project, a multi-disciplinary archive of Ogham stones; the project is digitizing and recording in 3D as many as possible of the approximately four hundred surviving Ogham stones in Ireland.

- Irish artist Brian O’Doherty remembers being taught Ogham as a child at Loughlinstown National School in Dublin in the 1940s. Christina Kennedy, Senior Curator at the Irish Museum of Modern Art, has written that Ogham became O’Doherty’s Rosetta stone, providing him with a means to unite serialism, minimalism, and language in his drawing and sculptures.

- Ed Yong, “The Wood Wide Web, ” The Atlantic, April 14, 2016.

- Noam Chomsky interviewed by Wiktor Osiatynski in “On Language and Culture,” in Contrasts: Soviet and American Thinkers Discuss the Future, ed. Wiktor Osiatynski (New York: MacMillan, 1984), 95–101.

- The Book of Ballymote is perhaps not as well-known as the Book of Kells, but it is an iconic manuscript, written in 1390 in Ballymote, in Sligo, Ireland. The first page contains a drawing of Noah’s Ark. The book also contains translations from the Greek on the destruction of Troy and the wanderings of Ulysses, followed by a resume of Virgil’s Aeneid. It also contains a treatise on Ogham and the earliest known key to Ogham.

- “Book,” Online Etymology Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/word/book.

- Manchán Magan, Thirty-Two Words for Field: Lost Words of the Irish Landscape (Dublin, Ireland: Gill Books, 2020).

- Dr. Nora White helped me understand this. From our email conversation: “Some of the letter names are problematic (H?, NG – possibly /gw/, Z – possibly /st/) in that we are not sure of the original sound, as inscriptions with these letters in clear contexts are lacking. The fact that they don’t occur much in our early inscriptions suggest that the sounds they represent were already lost in the language. It is summarized here: https://ogham.celt.dias.ie/menu.php?lang=en&menuitem=03.”

- Ogham is called an alphabet, but the word itself refers only to the characters. The alphabet is called Beith-luis-nin, named after the first three letters, just as the word “alphabet” is named for alpha and beta.

- Sitka spruce is a recent introduction to Ireland. The species was brought to Europe as a lumber tree and was first planted there in the nineteenth century. Sitka spruce plantations have become a dominant monocultural forest type in Ireland, making up 52 percent of forest cover and causing untold environmental damage to local ecosystems. As X is often used to represent unknowns, it felt right to represent it with Sitka spruce.

- A massive peat and Sitka spruce landslide occurred near Meenbog Wind Farm in Ireland on November 13, 2020.

- I am indebted to Robin Wall Kimmerer’s work exploring the possibility of using “ki” as a pronoun for nonhumans. See “The Grammar of Animacy” in Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants (Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions, 2013).