J. Drew Lanham is an ornithologist, naturalist, and poet. His writing and poetry combine conservation science with personal, historical, and cultural narratives of nature. He is the author of The Home Place: Memoirs of a Colored Man’s Love Affair with Nature, which received the Reed Award from the Southern Environmental Law Center and the Southern Book Prize, and was a finalist for the John Burroughs Medal. His essays and poetry can be found in Orion, Audubon, Flycatcher, and Wilderness, and in the anthologies The Colors of Nature, State of the Heart, Bartram’s Living Legacy, and Carolina Writers at Home. He is an Alumni Distinguished Professor of Wildlife Ecology and Master Teacher at Clemson University, and a MacArthur Fellow.

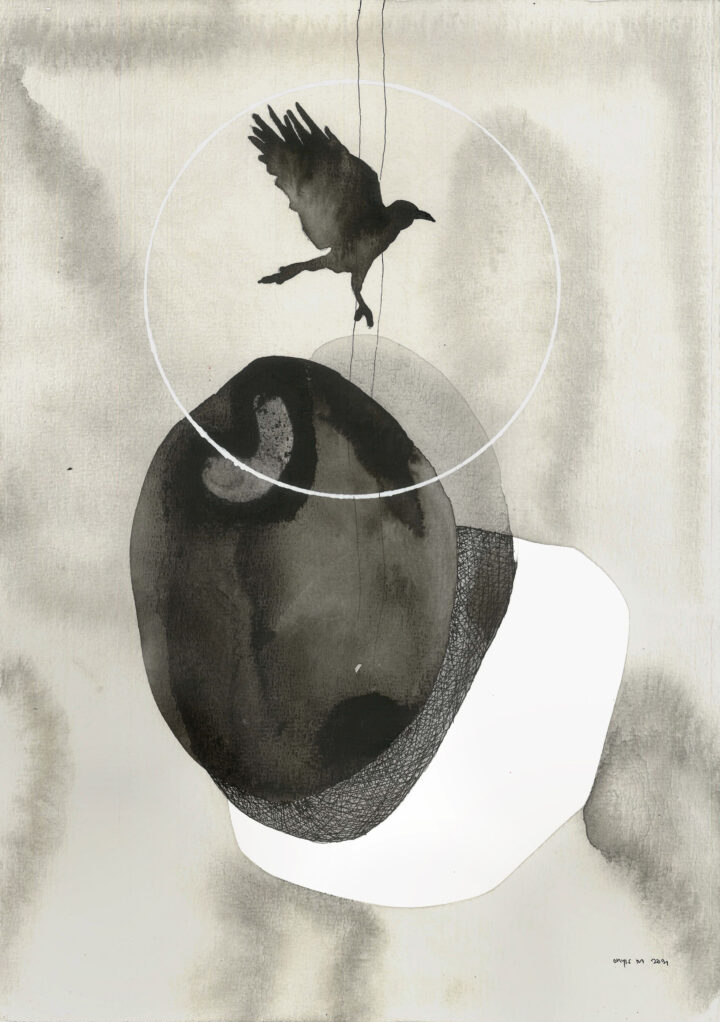

Onyis Martin is a Kenyan artist living in Nairobi who experiments with a wide range of materials, exploring the human condition and the global geopolitical interface, specifically through issues surrounding human trafficking, migration, corruption and displacement. His work has been shown internationally, most recently in Cape Town for a solo exhibition, Before Tomorrow Comes.

J. Drew Lanham imagines an exchange of letters between two pillars of conservation: one who extended his love of nature to care for a fellow human, and one who did not. Through this fictional discourse, Drew asks: In the ongoing response to racism, how might reckoning with history help us to widen our field of view and weave better futures?

We live in an age where identity, by whatever key, places us in pigeonholes. By race, ethnicity, gender/nongender, geography, political affiliation, occupation, and even vaccination status, we nest in certain identities where we are accepted by some and rejected by others. There are nests we choose but also those that are chosen for us. Although most term the current epoch the “Anthropocene,” the Age of Humans, I eschew this label in favor of my own tag: the “Ident-ocene—the Age of Who-ness.” It is in our identities—chosen and/or cast upon us—that we often worry over how to understand past sins, resolve present predicaments, and reweave who we’ve been and what we’ve done into better futures.

Identifying things is what I do for a living. An ornithologist and bird-watcher for most of my life, I’ve spent more than fifty years obsessed with identifying winged feathered beings. It’s become almost a reflex to call out a bird’s name as I would that of a good friend or family member. With that kind of familial intimacy, I follow the lives and plights of birds too. My work is to understand them so that I can teach others to respect and protect them. It just so happens that I am a Black man in a predominantly White field, and that does matter. Not to the birds, but to those who share my passion for watching and conservation.

Birders identify birds without consideration of their own identity. And while bird-watching can be an escape from the larger societal ills that often weigh us down, incidents like the verbal assault on a Black birder in Central Park—which made some of my longtime birder friends reluctant to venture forth, fearing the rising racism/bias and violence directed at their identities—remind us that no hobby is an island. One shouldn’t look up at spring warblers while trampling wildflowers underfoot. Being circumspect is a righteous thing. The flower certainly appreciates the consideration and, on account of that kindness, has the opportunity to bloom on. Oblivion can be a cruel privilege. The stepped-on thing is injured, crushed to death, perhaps, by a heedless passerby who doesn’t care beyond the next bird or is hurrying on. We must take the binoculars down to see the wider field of view, to not step on the unseen, to take history and its long trajectory into account.

As we search for western species ID’d with White men’s names, like Lewis’s woodpecker or Clark’s nutcracker, we should consider the impacts of Native genocide and land grabs in the American West—the places where ideals of wildness and wilderness protection reach pinnacles. Can we really celebrate ideals of untrammeled nature where whole nations were exterminated and the remainder forced into refugee status?

And should we ignore the history of enslavement on lands shaped by Black hands that now serve as conservation sites for struggling wildlife? In Lowcountry rice marshes, for example, endangered black ducks and black rails likely stand more of a chance because of what enslavement wrought back then. Hundreds of thousands of acres of forests were destroyed and millions of tons of mud moved—banked in dikes that if piled skyward could’ve been mountains—to grow Carolina gold rice. Structures called “trunks” and “gates,” engineered by the same Black bodies to hold the tide and then release it, weren’t just the products of free labor, but technology brought from Africa. Can we celebrate this altered landscape, now seen as beneficial for birds, without remembering the untold torture and terror that happened here to make White men filthy rich?

How do we view the people—the flesh-and-bone “monuments”—who built conservation and environmentalism in oblivion, ignoring truths of the wrongs done? Do we dethrone the heroes we’ve placed on a pedestal by remembering they were racist or grave robbers? Should we? Flip that coin to the other side. Why don’t we give higher standing to those who fought for good on multiple fronts? Does being an abolitionist and a birder diminish the latter? What responsibilities does one have beyond identifying birds properly by sight or sound?

As birding begins to reckon with its past in response to societal unrest and bias, we have a chance to consider two historical contemporaries who shared the privilege of White maleness in a white-supremacist country, undergirded by laws protecting, and an economy promoting, enslavement. They could both go about their wild, wandering business without worrying beyond the next bird they might see. One did just that. The other didn’t. Here, I offer the chance to drop in on a hypothetical letter exchange concerning two sides of an issue that would ultimately tear America apart. Two birding men: John James Audubon, the famed “father” of North American ornithology whose painted field guide, The Birds of America, serves as a holy text for birding, and who was also an enslaver; and Henry David Thoreau, the transcendentalist naturalist of Walden fame, whose anti-slavery activism is often whitewashed in favor of more “comfortable” narratives about his solitude-seeking ways. Each of them might be called “men of their time”—but then one made choices to stay stuck in the sins of the time, while the other chose to find a place on the right side of it.

What might one say to the other about something much more controversial than the identity of a sparrow? What differences might arise amid an earnest letter exchange between these two men who, despite their shared love of nature, are not aligned on the issues of their time? Here, I would ask that you suspend probability for the sake of possibility and expand outward into the imagining with me.

This imagined correspondence between Audubon and Thoreau occurs in 1847, as Henry David is nearing the end of his occupancy at Walden Pond and is becoming increasingly concerned over slavery, as evidenced by his participation in abolitionist activism. John James is an acclaimed frontier celebrity and is at a career high point as a published author and internationally known American naturalist icon. He is also on the cusp of physical and mental illness. Both men are White, privileged, and at or near the “top” of their respective games. John James died in 1851; Henry David, eleven years later, in 1862.

My goal in imagining this exchange was to capture White-on-White discourse about racism between “luminary men of their time” who, despite their love of God’s creation, did not share a love of Black humanity. I’m a fly on the wall of historical imagining; a swift in the chimney, listening to the correspondence as it is read aloud by kerosene lamp. I want the reader to feel the coldness between Thoreau and Audubon—and, yes, the immediate disdain between them too. I hope to let the reader in on the history that was and imagine the discourse that might have been.

So read on, reader, please, and let the creative exercise of bringing history forward bend your eyes, ears, mind, and heart toward the true goodness and moral right that bears the marks of timelessness.

Dear Mr. Audubon,

Greetings, fellow nature adorer and bird lover. By name I am Henry David Thoreau, a resident of a cabin in Concord, Massachusetts, near a great pond called Walden, where I have endeavored, for a short while, to live simply by my own wits and to depend upon wildness to inform my survival. Recently, I’ve been working toward bettering myself as a naturalist, and I came to learn of your wondrous affinity for the avian kind from a gentleman acquaintance hereabouts who saw your work in his travels to Europe a few years ago. His exhortations touting your artistry certainly whet my appetite. I journal my own observations in nature with what discipline I can muster, as I believe it important to record, within and between the seasons, what the creatures and plants are doing in relation to the environs around them. To whit, sir, I myself came across a volume of your Birds of America and was mightily impressed beyond expectations to see it in person. It seems to me that your subjects might very well up and fly from the page!

I am no artist, rest assured, but it occurs to me that we are both equal admirers of wildness in its many forms, feathered, furred, and otherwise. Whilst you have traveled further into the expansive wild than I—into forests and swamps, and even ventured into the West—I have, for the most part, remained more parochial. My beloved Walden Pond, though encroached upon by the burgeoning civilization of Concord, houses its own birdlife. The phoebe, whose migration you’ve marked for the purpose of determining its fidelity to Philadelphia, is equally at home here. I’ve noted its mossy nest tucked under the eaves of my parents’ home. Your portrait of this bird on a cotton plant reminds me that you have spent quite a bit of time in the South, whereas I have not. It is the same bird, I know, but you know it differently still.

And so I applaud you, Mr. Audubon, on the scientific achievement of your folio. It will expand our knowledge of natural history and ornithology immensely. As a fellow bird-watcher and naturalist, I’m grateful for your efforts.

But this, sir, is where I must depart in the strongest manner from you. The vociferous phoebe pair perched on those cotton bolls inspires me to write you on a subject close to the cotton you portrayed. Recently, I became aware of your companion notes and discovered “The Runaway,” the story of your encounter in the dismal bayou swamps of Louisiana with an escaped, enslaved black man and his family, whom he had regathered after they were sold off and separated from him. In this harrowing tale, you speak of how you met him, a beleaguered black man who had found his rightful freedom (rightful in that it should be afforded to every human being). At first, you are frightened by him, but then, after he treats you with the utmost respect and even shares his supper of wild game with you, you decide to repatriate him to the cruelty of slavery’s shackles—the whip, forced labor, and perhaps separation from his family again. This has firmly set me against you, Mr. Audubon. What sort of man can love the black crow—“mistreated,” you claim in your notes, “unduly prosecuted”—whose intelligence and resourcefulness in the face of such injustice merits your admiration, but then let his heart grow cold toward a fellow human being—also mistreated, like the crow—whose skin happens to be a darker hue? Sir, could you not have listened sympathetically to this liberty-seeking fellow and helped him secure it by assisting his effort, or at least left him to his own design, to be as free as your wild birds? What of his wife and children? Did you not see in his familial affections a reflection of your own? And then you call the man “happy” to be a slave again. How could that be, Mr. Audubon? How could any being with feathers or skin find joy in being trapped and imprisoned without choice or free will to come and go?

I must say, Mr. Audubon, I left my respect for you on that page and can no longer look at the birds you painted with such skill and, dare I say, love without thinking of your hate for human beings who do not share your whiteness. I know my fellow abolitionists have railed against you too. I will share that I would have done the opposite of the sin you committed in that swamp. I would gladly assist northward those following the “drinking gourd” toward freedom, beyond the hypocrites who would allow free men to be returned to cruel “masters,” as you did. This nation will reckon with this sin and heavily so. Though I am not a violent man, I fear striking blows may be the only way to stamp out this sinful contrivance.

I will continue to love birds, as I am sure you will. That passion we share, but none else. I pray that some force, Mr. Audubon—God, nature, or the next runaway you might meet who refuses, with a determined steely resolve, to be imprisoned by your obliviousness—changes your heart, toward this life or the hereafter. Had I been that man, I would not have gone lightly. And you, sir, I beseech you to look more circumspectly at this world, and not just at birds. I cannot sign respectfully, but only in truth.

Regards,

H. D. Thoreau

***

Sir,

I extend gratitude for your compliments on my work. It was a most arduous undertaking, for which I thank Providence for having bestowed on me some talent for portraying what I see in creation. The birds have inspired me to that end, as it seems they have you.

But beyond the superficial sharing of bird adoration, I must take umbrage, and vehemently so. You, living where you do in Massachusetts, where the negro is “free” to roam without responsibility or management, have had the wool of abolition pulled over those same eyes which show you the wonders of wildness. I know of this because I, too, have spent time in places where they are allowed the freedom of self-determination, almost like white men. As fortune would have it, in the southern region, where I spend a preponderance of my time (as the birds find the climate and environs more hospitable), the blacks are governed with discipline and civility—so long as they serve as beasts of burden and helpers of white men. To me, the science of skulls—phrenology, I believe it to be called—renders unto the thoughtful man the realization that some are meant to work and others to supervise them in a manner best suited to benefit all. My dear friend Rev. Bachman of Charleston, South Carolina, has assured me that this situation is on the right side of Morality and that God has wisely placed us—negro and white, slave and master—where we should be.

The poor, unfettered darkie soul I met in the bayou that night, though he would not say it, was, in truth, missing the security and care of his master and his comfortable cabin, where he would be assured of security, food, warmth, and work to occupy his lesser brain. Lurking out in the wilderness as he was, he seemed out of place, as his kind often do. Yes, the phoebe pair you mentioned were posed on cotton bolls, as I thought this an appropriate symbol of their favor toward open environs. I believe that the runaway I encountered—and his poor suffering, fearful family—belonged in those same crop fields, doing the will of their earthly and heavenly masters. I believe it was my duty as a white man and responsible citizen to return him, to restore lost property, which he and his family were by law. The situation you place yourself in by aiding the runaways there, I find as intolerable as you find my repatriation here. I hear the tinhorn cry of the negro liberators, and I prefer the tin horn calls of Lord God birds in the bayou, where I captured the slave. He should be happy that I did not collect him dead with powder and shot, as I did the woodpeckers.

Let the abolitionists complain as they might. Despite having the fortune to watch the birdlife of this nation as I please, my occupation bears no time to consider lesser beasts, especially those that the Divine has marked as servants of our needs. The times we live in dictate that I be master of the negroes you pity, who can do nothing for me beyond portage and assist. Do not bother yourself, Mr. Thoreau, with further correspondence to me, as, upon spying your self-righteous name as sender, I will ignore it. Stay there in Concord on that small pond with your free negroes and watch the birds with them, if it pleases you. They will prove ruinous to the joy that birds bring the truly dedicated watcher.

They are, by God’s right, for the white man’s joy.

Forthrightly,

J. J. Audubon

***

And so I ask you, reader, taking these histories into account, taking a wider field of view, taking care not to trample upon the unseen: how will you come to a deeper understanding and help weave better futures? As we continue to live in a white-supremacist society, where are our guideposts for true goodness and moral right? As we look for the birds in the trees, what must we take care to see alongside them, and how do we ensure that our love extends to all beings?

So with whom would you like to spend a day afield? John James Audubon or Henry David Thoreau? No, it isn’t that Henry David was perfect. He was not, and the ever-sharpening shovel of retrospect may find slights in his record too. But for me, now, in this twenty-first-century body of a Black man, birding, whose enslaved and Jim Crow–ed ancestors didn’t have the same freedom and choice to seek the singing thrush, it’s not even close. I’m headed to Concord.

Joy Is the Justice We Give Ourselves

In this poem, J. Drew Lanham celebrates radical acts of joy by lifting up liberation, reparations, justice, and deep connection to ancestors and the living world.