Elizabeth Rush is the author of The Quickening: Creation and Community at the Ends of the Earth and Rising: Dispatches from the New American Shore, a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. Her writing has appeared or is forthcoming in The New York Times, The Guardian, Harpers, Granta, Orion, and others. Rush is the recipient of the Howard Foundation Fellowship awarded by Brown University, the Society for Environmental Journalism Grant, the Metcalf Institute Climate Change Adaptation Fellowship, and the Science in Society Award from the National Association of Science Writers.

Elizabeth Rush reflects on climate change as a transformational force on our landscapes and the words we might use to grasp this shifting reality. Her book Rising was named a finalist for this year’s Pulitzer Prize for its rigorous reporting on America’s vulnerability to rising seas. This essay is an account of the days she spent driving through the Pacific Northwest while on a tour for the book—a time of wildfires, loss, and possible futures.

So it was in summer again the loved ones went out to

the sea at a quarter to dusk

The part of them that could do nothing did nothing

& the light of them walked along

—Brenda Hillman, from “Poem for a National Seashore”

Mile 0

At the car rental counter, the clerk asks me if I am sure I want to downgrade my Dodge Challenger to a Volkswagen Beetle. “You paid for a Premium vehicle,” he says, trying to make me understand that I am throwing money away. “But the Volkswagen will be more fun to drive,” I say. The attendant circles the silver car twice, looking for dents, and I follow him feeling like slightly less of a fraud. What I don’t say is that my mind is a cleft thing: one side calculating the carbon cost of running up the coast to promote my book on climate change, the other strangely comfortable in the subterranean parking garage with its Explorers, Grand Cherokees, Beetles, and Corollas. Corolla, as in the petals of a flower, the whorl that encloses the reproductive organs. The clerk notes a couple things on his clipboard, then drops the keys into my open hand.

Mile 33

In the spare room of an old friend’s house in Oakland, I wake up thinking about the poet Arthur Sze in New Mexico and his water ditch. A couple months ago at a reading of his, I listened to him describe the intricate system of canals that connect his property to the local reservoir. He has an allotted time every week when the water is his; accordingly he walks the ridge above his house to lift the water ditch’s gate. In flows the liquid, filling cisterns so he and his wife might bathe, might water their plants, might make tea and wash their dishes. Water is both noun and verb. Something solid and some human motion.

I won’t try to paraphrase the poem Arthur wrote. But know it has none of that, no bathing or making tea. Instead there are magpies, and straight edges, and circular saws. Dandelion stalks, peanut butter, rat shit, and PVC. Basically, every thing that could be in the poem is in the poem. It’s there because of a deliberate act. Arthur woke. He walked toward the water and lifted the gate.

“Was the promise of labor, I mean the regular maintenance of this thing that we depend upon, part of why you bought that house?” I asked Arthur after the reading. I was hoping he would tell me that he chose to be drawn, again and again, to the water’s edge. “It has turned out to be a lot of work,” he said instead, matter-of-fact.

Mile 77

After the event at the science museum and after the walk in the botanical gardens and after the food shopping at Berkeley Bowl, I drive north to Point Reyes and hike to Coast Camp.

In this exact cove, just south of Limantour Beach, there sits a decomposing blue whale, the largest mammal on Earth. I encounter the baleen first. Jet black and so shiny it seems it could be plastic. When I see it I think: insides of an air conditioner. But then I draw closer, reach out to touch what is there. The pliant pieces, each ending in a flutter of hairy strips that bend but will not be separated from the rest.

Just down the beach there is a little something left, some vague body, syrupy yellow. Soft slag heap. I suppose this is the part that smells. I have not been brave enough to scan the mass in search of the animal’s eye. But I did touch a giant vertebra picked bare and said out loud, “You were a beautiful whale.”

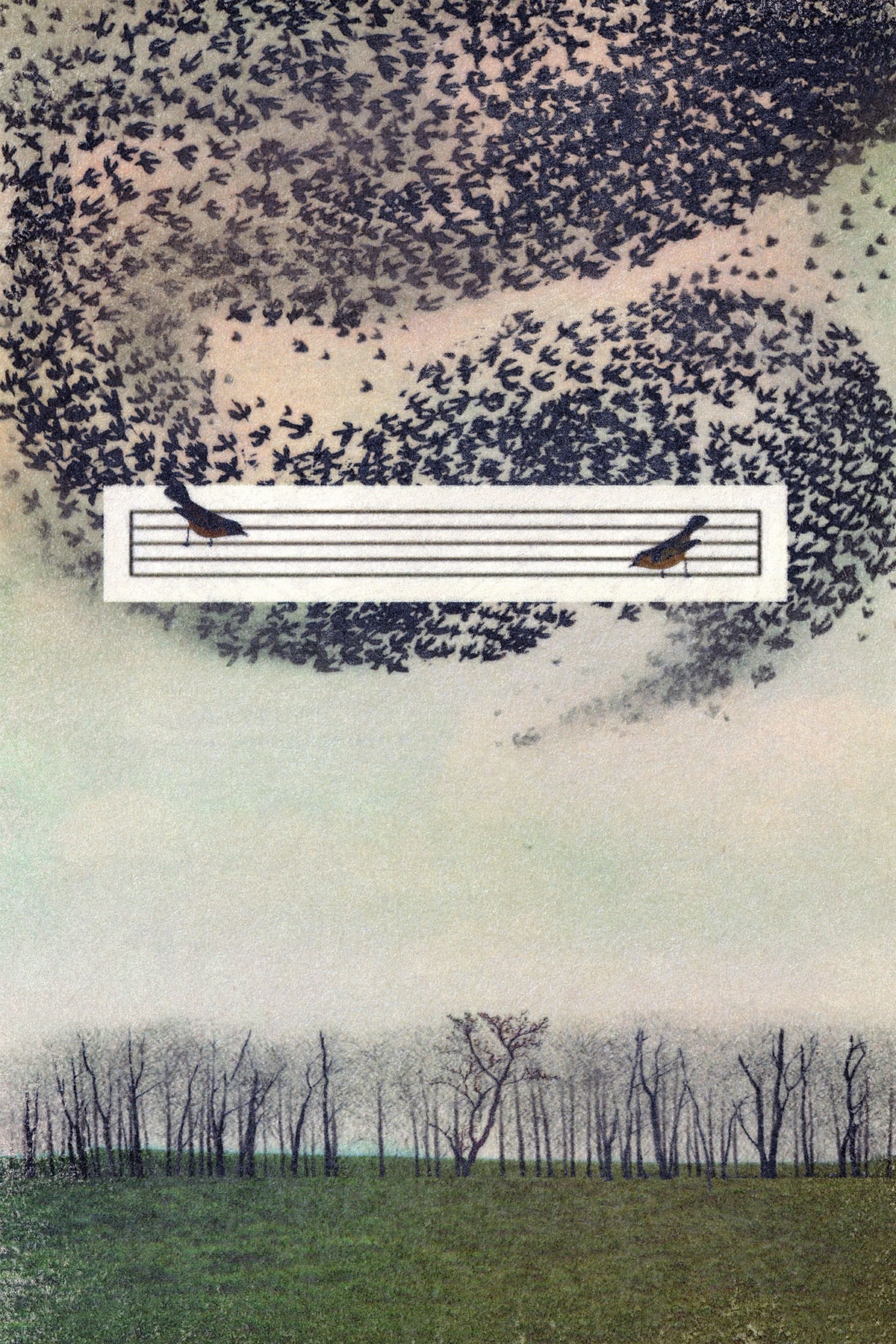

A man in a straw hat and a woman in a vest and two kids—theirs I suppose—tell me that this young whale was struck by a shipping boat. Its spine severed. The sky is suddenly shot through with birds and the people all look up in unison. Love, we will raise our children in a world where this happens.

The tide rises and the waves around the whale carcass make momentary puddles of foam that turn blue, turn black, then sink into the sand. Littoral, one of my favorite words in the English language, in part because it sounds like literal, that belief in physical matter. Littoral—an in-between place where land meets sea, where language meets orality.

Listen. Here, the-things-that-are manifest words—say that many of our answers are already outdated and others are much older than our greed. Husks of mollusks, gull feathers caught in grasses. Stomach tight with sickness that moves through the body in waves.

My back rests against a bleached piece of driftwood, the trunk running perpendicular to a vertical cliff the color of dried wheat. It hems in the beach, the whale, and me. If I sat here long enough, I could watch all of this literally disappear beneath an ocean made heavy with water from the poles.

And in that ocean, seals. The sea is so clear that when they dive down I can watch their bodies go all S-shaped. There is a kelp forest offshore, and sometimes I mistake the bulbous ends of dulse for a seal’s slick face.

Some humans stop to take photos of the whale’s rotting body because we don’t know what we are supposed to do. Because we think documentation might somehow make this loss endurable. Before I walk closer I put on my sandals. I rise but cannot find the eye.

Mile 78

This morning I woke to deer, mother and child, grazing on the hillock above my camp. Woke to: a dune-colored hummingbird, heading south; bunnies rustling in the underbrush. Wild peas—pink and flame, entwined with the pines they rise upon. The click of bird claws on the picnic table; bees checking out my honey. Woke up already arrived. Dew on the rain fly and the ocean hissing beyond the cliff.

Mile 86

I read in The Battle for Paradise that after Hurricane Maria, Dalma Cartagena taught her students to grow vegetable plants from seed. When they touch and tend to the sprouts, they begin to recall that despite the storm’s violent rending, they are always also part of something that is protecting them, nourishing them.

Here in Point Reyes, eucalyptus steeps in the dry air.

What if, instead of knocking on wood every time I say Felipe and I are going to try to have a family, I felt rich with possibility instead? What if it isn’t just my age that makes me uncertain we will be able to conceive? What if it is also because I dwell in our world’s dwindling?

Today on the trail, however, the feeling of loss did not live inside my body. Instead my body was just a body walking down a path. The fog worked its way toward me. It came in sheets of cool, jeweled air.

Mile 98

Literary pilgrimages braid word and world. I start the day with a Robert Hass poem, the one that opens this way: “Tomales Bay is flat blue in the Indian summer heat.” Hours later I sit on a log at the water’s edge as the actual place unfurls: wide-winged predators, tidal channels, and the bay beyond. Tule and verbena and the sound of blue thistles touching in the dry heat. In the marsh, I found a deer hoof—just the hoof—skin still on the shin. The shin snapped clean right above the ankle. There were flies in the air, though I did not see the carcass anywhere.

The soil here is damp and dark. I sit surrounded by a sea of swollen-fingered succulents. People call this plant pickleweed because—well, because it looks like a bunch of pickles got together and formed a forest of bonsai pickle trees. Soon this forest will be underwater, not just temporarily but for good. Which is another way of saying I can’t stop thinking about the old maps and their moving edges.

Down at the marsh lip, next to no movement in the heat of midday. Still deeper in the soil, the rhizomatic language of bullgrass roots, the things they say during flight.

Mile 102

Today Black Mountain is on fire. The dark edge of the blaze looks like one long blood clot. People pull over, exit their cars. The police have cut us off at the pass. Binoculars out. Phones out. No one says anything, then back into the Prius and the pickup truck and the Volkswagen Beetle. We turn around and try to get to Petaluma another way.

My mother called last night. She didn’t want to know about the book tour or my walks. “How close are you to the fires?” she asked. “Don’t worry,” I had told her, “I am nowhere near the burning.” At the time it was true. But now, in my rearview, fingers of fire flare.

I drive to town and talk with the local bookseller. She says, “You know last summer when Napa was on fire, people fled here, thinking it was safe.” The woman who owns the consignment shop leaves the store behind, walks into the street and stares.

Mile 147

Elise and I are four miles into a five-mile hike when a ranger appears and tells us we need to evacuate. Suddenly, helicopters. Dangling beneath each one a bladder heavy with water. Hot blasts of air hit my body. We are almost running now. A plane flies low, pours a pink powder onto the blaze.

When we tell Elise’s mother, she declares, her voice a-warble, “I just can’t take this anymore.” We are standing in her kitchen on Redwood Road, the kitchen that she evacuated the previous year when the wildfires were so close. I walk half a mile northwest to see what remains: three foundations, a chimney, redwoods with soot-scarred bark.

We pour ourselves glasses of white wine, easing the desire to run. During the blue hour on the edge of night, bats congregate. Beyond the vineyard coyotes talk about their kill. Tomorrow morning we will eat the eggs the hens laid. Tomorrow we will try not to wander beyond rescue distance.

Mile 164

The next night, at the local public library, residents say they feel alone with their fear. They question whether they should stay or go; whether a fire will eat their home or their family. One woman in a lime green dress speaks of her parents’ place along the Sacramento River and the trouble with floods. Another relocated to Napa to be with her ailing mother, and now she is thinking that they ought to leave together. “But where to?” she says, trailing off. And in that silent space, where wonder takes hold, another woman picks up the narrative line.

This is how water moves, remaking what it does and does not touch. Too much water or too little; both are equally unsettling.

Just as telling a story allows the speaker to encounter their experience anew each time they labor to give it shape—and to learn something different with each retelling—being attentive to story develops our capacity to listen. The more floods and wildfires I hear about, the more hours I spend at the edge where water and land meet, the less inclined I am toward linearity, toward the idea that all of this loss will inevitably deliver us to some already determined future, where loss is all there is.

Mile 400

For the second time since setting out, I fill the gas tank. I buy a cold kombucha and roll down the windows, letting the smoke in. On the radio “I Say a Little Prayer for You” is followed by “Don’t Play That Song for Me.” Days later I will learn that Aretha Franklin has died.

Mile 682

The smoke stays with me up into Oregon, through Grants Pass and Cave Junction. Because of it, Crater Lake National Park is mostly empty. At the trailhead there is a chart: when you cannot see more than five miles, the air quality is bad; when you cannot see more than three miles, the air quality is dangerous; when you cannot see more than one mile, you need to leave. I squint across open space. The far cliff walls are almost indistinguishable from the sky. My map says 6.2 miles separate here from there.

Wander down from the volcano’s rim to the lake edge, then dive in. Beneath the surface I open my eyes to piercing cobalt. It is the first time in over a week I can see clearly. The dark lava scree falls away precipitously until all is blue on blue, its brightness bracing. The color so close to perfect it helps me forgive a hurt I carried here and could not before let go.

Fiona has joined me at the lake. There is a small child growing inside of her. We would light a fire if it were allowed. Instead we boil water on the camp stove for tea and talk about the stars we cannot see.

Mile 940

My friends in Portland and I drive out the Gorge to Rooster Rock. We sunbathe with infants on a sandbar in the middle of the Columbia River. A couple walks by, wearing only wide-brimmed hats. The air is thick and tastes like prayer papers burning. Tommy tells me that last summer was worse. On the Fourth of July, the woods surrounding Eagle Creek and its seven waterfalls were on fire. The trail, just north of here, has yet to reopen. He tells me that Cougar Hot Springs is burning now.

The precipitation maps are contracting. The line between rain shadow and drought shifts uneasily like a tired body in a tired chair. Together we watch the water’s edge wobble. We wonder what to call the feeling of losing the places that shaped us, a word for the way our very lives drive them further and further into the past. We eat strawberries, lean baptismal into the silty river, then click their babies into dirty car-seats and head home.

I ask the midwife among us to recommend books on motherhood. After my reading I buy a used copy of Anne Lamott’s Operating Instructions: A Journal of My Son’s First Year. It is the only thing I have ever purchased with a baby on the cover. I feel like I have a secret, poorly kept.

Mile 1,296

After speeding up the 5 to pick up my father at the Seattle airport; after singing “Under Pressure” as loud as I possibly can, not caring if I blow out my voice; after the last reading and after drinking prosecco to celebrate the success of something that is also part elegy, a record of what we have already lost, we try to leave it all behind and discover again what we already know: that nothing separated us from the environment in the first place.

My father and I came to these mountains once before, fourteen years ago. I remember the green tongues of wildflowers licking down the hillside and how stunning it was to see—for maybe the first time in my life—sharp snow-covered peaks. Now the canyon walls just northwest of Newhalem are covered in charred trees.

Together we walk the Diablo Dam trail. Don’t see much when we look out; the close peaks are blue bumps and beyond them only white. We eat gala apples and licorice flown in from Australia. Above us electricity sounds twitchy in the wires. The sun is a nectarine in a sea of soot. Down here on Earth we are still a father and daughter in a forest, sometimes speaking. Still the sparks of some human dream, throwing our small light.

Our campsite has no showers, only the river and its riprap, which those who stayed here before us used to make a little rock wall. They stacked stones to hold the water momentarily in place so that they might bathe. For a very long time I look at the stranger’s work—labor at the water’s edge—then stand and touch the cold creek that runs through this temporary home, connecting it with the abyss.

In the darkness I wake to the rushing river noise—think: here a river is also a melted glacier—and fall immediately back to sleep. In the morning the smoke has cleared some and the mountains at last come into focus.

There the specificity of each Douglas fir—both those that live and those that are but burnt husks—is startling.