Fred Bahnson is the author of Soil and Sacrament, and his essays have appeared in Harper’s, The Sun, Orion, Oxford American, and Best American Spiritual Writing. His essay “On the Road with Thomas Merton,” originally published in Emergence Magazine, was selected by Robert MacFarlane for Best American Travel Writing 2020. He is a recipient of a W.K. Kellogg Food and Society Fellowship, a North Carolina Artist Fellowship, and a Terry Tempest Williams Fellowship for Land and Justice at the Mesa Refuge. He lives with his family in southwestern Montana.

Fred Bahnson reflects on the life of Barry Lopez, a storyteller whose encounters with mystery and the more-than-human informed his practice of writing stories that illuminate and heal.

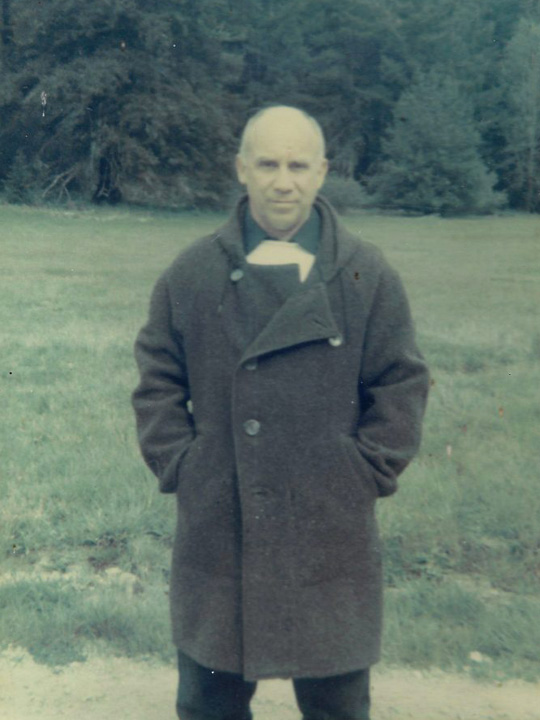

When I first arrived at the home of Barry Lopez one November day in 2018, he pointed to a fresh Douglas fir stump and said, “We had to put down that tree.” The Douglas fir was one of many old-growth trees surrounding Barry’s home at Finn Rock, Oregon, along the McKenzie River. The tree had become diseased and Barry worried that it might fall on the house, so a few days before my visit, he and a neighbor got out their chainsaws and put down the tree. That’s the phrase Barry used, put down, as one might speak with regret after euthanizing an animal.

Thirteen years earlier I had discovered Barry’s work and knew I’d found a writer I wanted to learn from. He wrote convincingly about the power of the natural world to heal us, about numinous encounters with wild animals, about the seemingly forgotten qualities of reverence, mutuality, and ecological humility he found in traditional cultures. Though ostensibly I was there to conduct a magazine interview, I’d really come because I was in despair over the state of the world and haunted by old childhood wounds, and in Barry’s words I’d found a measure of solace for what plagued me. The healing I found there, I learned in the years after my visit, was real for many people. The writer and editor John Freeman describes Barry’s work as “a prosthetic of kindness,” an appendage to help us face the anomie and dislocation of our modern age.

When I suggested the interview, Barry and his wife, Debra Gwartney, offered to host me for three days in their guest cottage. Each morning Barry arrived at the door sporting a pair of worn cowboy boots, faded jeans, an old plaid work shirt, and a 1970s-era down vest with a duct-tape patch on the right shoulder. I’d get a fire going in the woodstove.

For the next several hours our talk would range as far as Barry’s imagination took him, which was so very far, covering the breadth of the ninety countries he’d visited in his travels, the long span of human and geological history, and the depths of evil we’re capable of inflicting on one another—and which he himself had survived in his own childhood. Barry’s reputation as one of our preeminent nature writers had long been established; his corpus included more than a dozen books of fiction and nonfiction and the National Book Award–winning Arctic Dreams. Soon after my visit in 2018, Knopf would publish Horizon, a monumental work in the making for thirty years, in which Barry described the ecological and moral horizons we face as a species. During my visit we talked of many things—the importance of elders, the difference between a boundary and a horizon, the need for vulnerability on the part of the storyteller—but underneath our conversations was the knowledge of Barry’s own horizon as he faced the late stages of metastatic prostate cancer.

No longer able to travel as he once did, Barry was preoccupied by what he called “a pressing question.” In a cancer-survivor group, an older woman who was a therapist and former nun had asked Barry: What is your second ministry? Though he’d grown up Catholic, he had left the Church without rancor or regret, seeking holiness and mystery instead in the natural world. The language of ministry was not his. But the question nagged him nonetheless, for it reminded him of the need to face, even in his diminished state, the question he’d been asking for most of his life: How can I be of service? And in what does that service consist?

Barry was also preoccupied with the unseasonably dry weather. We had our recorded conversations each morning, and when Barry’s energy flagged, we would step outside onto the guesthouse deck and stand under the firs, watching the river’s current. The McKenzie River valley is a temperate rainforest, but that year brought drought. During one of our breaks, I remarked at the quality of light filtering down to the forest understory. Barry was silent for a moment. “I must tell you,” he said, “it’s very strange in November to have this much clear weather. The reservoirs are empty. I’ve never thought about this, because you think you live in an unchanging environment, but this might shortly become a place in which it’s not good to live.”

How could this lovely river valley not be a good place to live? “Because of the fires,” Barry said. There was no question of moving, however. As he told me, “The cells of my body have been shaped by what’s right here in front of us.”

The cells of Barry’s body had been shaped and nourished by the forests and waters, the salmon and beaver of the McKenzie, but they also were under attack. By December 2020, the prostate cancer advanced too far, and he decided to enter hospice care.

On Christmas Day, surrounded by his family, Barry Lopez slipped quietly from the world.

In the weeks since Barry’s passing, I’ve been returning again to his pressing question, the question of service, what he called in Arctic Dreams “the desire for a safe and honorable passage through the world.” When we spoke in early December, it was clear this was still a live question, especially when he described a decisive moment more than fifty years earlier when he nearly became a monk.

It was fall 1966. Barry had recently graduated from Notre Dame and landed a job as a sales representative with Signet Mentor. He could hawk textbooks to college professors by day and write by night, a perfect job for an aspiring writer, except for one nagging thought: Did he have a monastic vocation? He was captivated by Thomas Merton, the famous writer-monk whom Barry had begun reading at Notre Dame, and who lived as a hermit in the woods at Gethsemani Abbey, a Trappist monastery near Bardstown, Kentucky.

“I was enamored—intensely enamored—of that life at Gethsemani,” Barry told me. His bookseller job required him to attend a conference nearby in Ohio, so he decided he would first visit the abbey to find out just how enamored he was. Should he become a monk or stay in the world and become a writer?

Barry remembered attending Mass with the monks and seeing their immaculate white robes, knowing they would later trade those robes for work jackets and muddy boots before heading out into the fields. The Trappists lived a life of medieval austerity. They rarely spoke except through sign language, slept and ate little, and spent most of their time either in prayer or performing arduous chores. As William James wrote, every individual soul works best under a certain steam pressure. Trappist life was attractive, but Barry worried that it would be a comfortable nest, and he was too young to settle into a nest.

The decisive moment came during a walk around the monastery grounds. Barry recalled walking past a door in one of the outer walls. Approaching the door he noticed a smaller opening at head height, a kind of window-within-a-door, which allowed him to peer into the inner cloister and its gardens. He saw two monks walking along a road toward a dairy barn in the distance. They were signing to each other, obviously engaged in earnest, albeit silent, conversation.

Barry thought: “Everything I want is right here. Spiritual context, physical labor, friendship—so it can’t be right.”

He moved to Oregon, deciding to become a writer. In 1970 he bought the house along the McKenzie River that would be home for the next fifty years.

As I reread Barry’s work, it seems to me that the monastic impulse never abated. It simply expanded to include the whole world. His seeker’s vision that would have been confined by a monastery’s walls reached out to every horizon it could behold, from Skraeling Island in the Canadian Arctic to Australia’s Nullarbor Plain, guided all the while by a belief, as Barry wrote in Horizon, “that the physical land … is sentient and responsive, as informed by its own memory as it is by the weather, and offering within the obvious, the tenuous.”

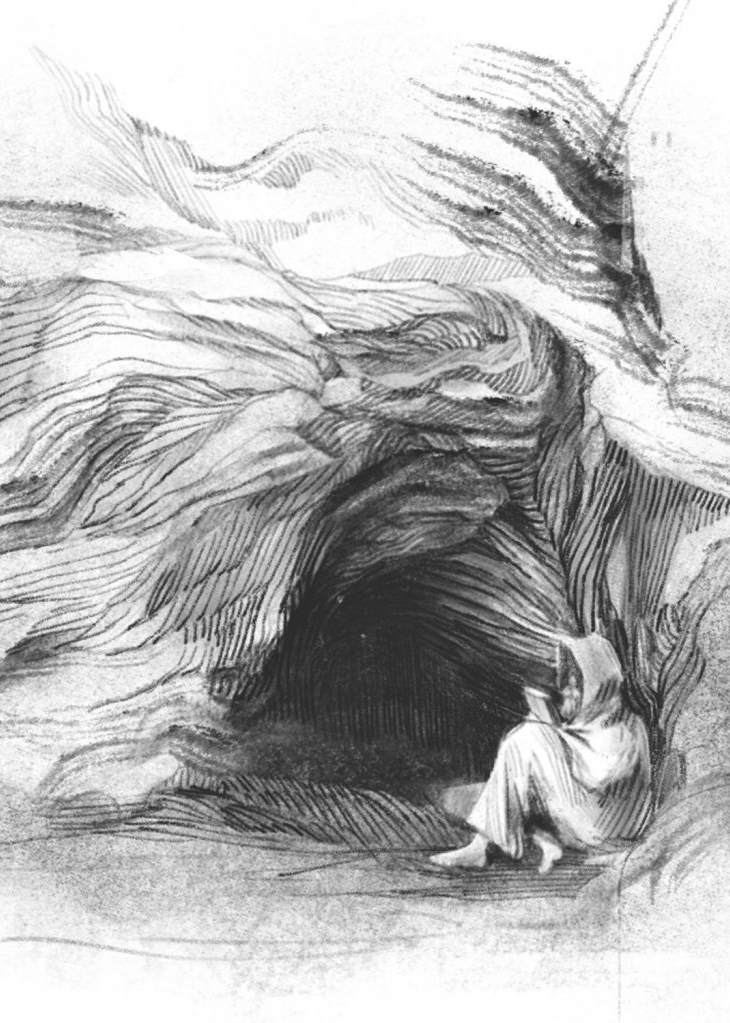

This search for what one of Barry’s fictional characters called “the foundations beneath the ephemera” is one of the lasting qualities of his work, and it’s everywhere. One of the chapter titles in Arctic Dreams is “The Intent of Monks.” Standing on a cliff looking out to sea, Barry watches a narwhal “as still as a cenobite in prayer.” In Horizon, he describes the polar expanse of Antarctica as “the geography for an anchorite.” It is a mystical vision, one that finds powerful expression in his short stories.

I’m thinking of “Pearyland,” in which a wildlife biologist named Bowman recounts his discovery of a place in the high Arctic where animal spirits wait to receive their bodies. Or “The Letters of Heaven,” in which a young boy in Peru discovers the secret love letters of two seventeenth-century saints, Martín de Porres and Isabel Flores de Oliva—also known as Rose—whose passion for each other spilled over into selfless compassion for the needy, which “they gave away in all the dark corners of Lima.” In “The Construction of the Rachel,” a recently divorced man goes to live at a Benedictine monastery in California’s Santa Lucia mountains and spends months building a model ship, only to discover that when he sets it afloat in the ocean, the model becomes a full-sized, nineteenth-century sailing vessel. He and the monks climb aboard and set sail for the Isles of the Blessed.

John Freeman, founder of Lit Hub and publisher of many of Barry’s essays, described Barry’s fiction like this: “The voice is patient, wandering, thoughtful and exposed—that’s what is so unusual about it in American fiction by a white writer, the way the voice in Lopez’s fiction is trying to situate itself with care and respect to older and more complex ways of knowing.”

I’m haunted by one story in particular. In “Teal Creek,” the fictional narrator recounts his strange fascination with James Teal, who came to settle in the Magdalena Mountains of New Mexico. Teal was tall and lean and walked with a slight limp, which might have been a war wound. He was seldom seen by the townsfolk, building a cabin on Teal Creek far up in the mountains. An anchorite. Several times over the years, propelled by his desire to meet Teal, the narrator hikes up the creek but each time turns back. On one approach he feels a certain dread as he nears Teal’s cabin. “It occurred to me that maybe Teal was dealing with menace,” the narrator says, “that out here he went chin to chin with an evil I could not imagine.” Years pass. On his next attempt to meet James Teal, the narrator hikes up in a downpour and finds him out past the green rows of a new garden. Teal is standing on a treeless bench of land, and we’re given this extraordinary description:

[Teal] was bent far over before the flat gray sky in what appeared to be an attitude of prayer or adoration, his arms at his sides. The rain had plastered his shirt to his back and his short black hair glistened. He did not move at all while I stood there, fifteen or twenty minutes. And in that time I saw what it was I had wanted to see all those years in James Teal. The complete stillness, a silence such as I had never heard out of another living thing, an unbroken grace. He was wound up in the world, neat and firm as a camas bulb in the ground and spread out over it like three days of weather.

A person wound up in the world, firm as a camas bulb—that was also Barry. He assumed a prayerful, listening posture in whatever place he landed, whether it was researching human origins in the Turkwel River Basin in East Africa or uncovering human indifference at a former child penal colony in Tasmania. While traveling in Alaska’s Brooks Range, he stopped to bow before the nest of a horned lark. “In such a simple bow from the waist,” Barry wrote, “you are able to stake your life, again, in what you dream.”

That gesture of adoration—the deeply human urge to genuflect before the world’s mystery—threads through Barry’s life and work. In the final chapter of Horizon, he describes a moment driving to Port Famine at the tip of South America. As he passed a lone man walking along toward him on an empty road, a rainbow appeared in the distance. Of that moment he writes, “We go on professing confidently what we know, armed with a secular faith in all that is reasonable, even though we sense that mystery is the real condition in which we live, not certainty.” A spiritual vision, yes, but one inspired more by place than by any religious tradition. During my visit in 2018, as we sat beside the woodstove in his guest cabin, I asked Barry what it is looking back at us through the eyes of a wolf, say, or from a particular landscape. Some would call that God or some other word for the divine. How would he name it?

“I would say it’s an encounter between the two sides of a lopsided divorce,” Barry said. “It’s a breach, you know. If you can imagine a divorce in which only one member of the dyad—modern humanity—made the decision to create a breach and then enforced it, you can begin to understand what the growing malaise in human culture is about. It occurs to humanity that it has lost its spouse.”

When Barry was traveling widely across the Arctic in the 1970s and ’80s he spent a lot of time among Inuit communities, and in each village he would ask people there what adjective they would use to describe white North American culture. The word he heard repeatedly was lonely. “They see us as deeply lonely people,” Barry told me, “and one of the reasons we’re lonely is that we’ve cut ourselves off from the nonhuman world and have called this ‘progress.’” Such numinous encounters in nature are moments of reconnection, part of the human search for reciprocated love.

“One of the reasons we’re lonely is that we’ve cut ourselves off from the nonhuman world and have called this ‘progress.’”

Like his fictional anchorite James Teal, Barry Lopez also confronted menace, going chin to chin with the evil of childhood sexual abuse. In the January 2013 issue of Harper’s Magazine, Barry published an essay called “Sliver of Sky,” in which he describes, in language as precise and spare and damning as any legal brief, the abuse he suffered as a child. “The Harper’s piece,” as he referred to that essay in our conversations, chronicles the serial rape he suffered at the hands of a fraudulent medical doctor from the time Barry was seven years old until he was eleven.

The one thing that calmed Barry during those years of abuse was contact with the natural world. But even the healing power of nature was not enough to quell the lasting trauma, and for years Barry struggled to deal with it on his own. “I’d spent enough time dealing with this—memories, disruption, some chaotic corner of darkness that was always apparent—and I thought, ‘I need to be done with this,’” he told me. He started therapy in 1996, and it lasted four years. The metaphor he used for the process was an image of him and his therapist sitting opposite each other at a clean, wooden table. Onto that table, he laid out all the components of his trauma. For the child, those traumatic events were defining, but during those four years Barry rearranged the components to create a new story, until the trauma was no longer the organizing principle of his life. When he was done, he knew he needed to write an essay, as he told me, “with as much objectivity as I wrote the polar bear chapter in Arctic Dreams.” The desire to write about those dark years was subliminally motivated by something a friend had said to him years before. “‘Your work is so comforting for people who have been wounded,’” Barry recalls the friend telling him, “‘But we all wonder, do you really know what it is to be wounded?’ And I thought, yeah, actually I do, but I’m not ready to say anything about it.”

Barry didn’t write the Harper’s essay because it was cathartic or because he thought his personal suffering was a story worth telling. “What I went through is irrelevant for me as a writer,” Barry told me. “People die every day in miserable ways, so another person living through difficulty is not even news. What is news is if one person can get on the other side of that suffering and say, ‘This is how it worked,’ and if you write well, what you’re offering the reader is a narrative they can subscribe to and change the parts according to the incidents in their own lives.”

That was one of Barry’s gifts, the way in which he decentered himself in service of the story. The writer’s job, he believed, is to give language to pain or injury or injustice. “The one skill a writer must have is the ability to make meaningful patterns, in the same way a dancer or choreographer or a composer makes patterns,” he told me. Those patterns “prompt an emotional or intellectual response. You achieve a level of clarity as a reader that you hadn’t been able to achieve before.”

During those three days at Finn Rock we came back many times to the cultural and spiritual role of story, especially Barry’s love for “the way story reconstitutes, reorients, and elevates human beings.” He saw storytelling as a kind of stewardship. “My particular reason for writing is to provide illumination for a nation that is chronically, pathologically distracted,” he told me. He wasn’t interested in writing those everyday stories that entertain or make us laugh or create conviviality—what he called maintenance stories. Three-meals-a-day stories. They might fill the belly, but they don’t nourish. “The stories I’m trying to write, and which I want to promote, are stories that contribute to the stability of my own culture,” Barry told me, “stories that elevate, that keep things from flying apart.” As he said in an interview in The Believer, “In the process of telling a story, and also of listening to a story, the teller remembers what he or she represents in a community, and the listener remembers what they want their life to mean.”

In Horizon, Barry suggested that the culture hero—Prometheus or Siddhartha Gautama or Odysseus—is no longer relevant in an age when humanity is exceeding ecological limits. The scale of the problems we face in the Anthropocene, the era in which humans have altered the very bone structure of the planet, are simply beyond the lone hero’s ability to fix. I asked him what stories should replace the lone-hero story.

“They haven’t been written yet,” Barry said. “We need new narratives, at the center of which is a concern for the fate of all people. The story can’t be about the heroism of one person. It has to be about the heroism of communities.”

It’s a profound idea—that our world is changing too quickly for the lone-hero story to be of much use any longer—and yet how to tell a story that puts community at the center? “A story is merely a pattern that signifies,” Barry told me. “The blueprint for our story is before us all the time.” Like a murmuration of starlings, for example. Barry recalled driving beneath the ample skies of California’s Central Valley and being witness to starlings by the hundreds “carving up open space into the most complex geometrical volumes, and you have to ask yourself, how do they do that?” Each bird looks to the four or five birds immediately around them to coordinate its movements, he explained. “To behold starlings is to take in something beautiful, a coordinated effort to do something in which there’s no leader, no hero.”

Starlings show us a way around the dilemma of scale, a model for human cooperation and deference toward others. A murmuration shuns the idea of genius residing in one individual, and recognizes that genius is actually possessed by the community. Human genius “might rise up and become reified in a single person in a group,” Barry said, “but it doesn’t belong solely to that person.”

Even as he prized the wisdom of community, one of the paradoxes of Barry’s life was the way in which a particular genius rose up and became reified in his own life, and he put it to work not only in his writing, but in his role as mentor, teacher, and supporter of other writers and artists.

Laura Dassow Walls, author of Henry David Thoreau: A Life and a professor of English at Notre Dame, has begun work on a biography of Barry Lopez. When Texas Tech University approached Barry about buying his papers, she told me, he agreed, but only on the condition that other writers would be included. Thus began the Sowell Family Collection in Literature, Community and the Natural World, a collection of papers from writers like David James Duncan, Gretel Ehrlich, David Quammen, Gary Paul Nabhan, Pattiann Rogers, and over two dozen others. “I love that notion that Barry didn’t want to be the lone tree, or the lone mountain rising up out of a plain,” Walls said. “The tree needs a forest, so you grow the forest.”

During my visit in 2018, after the long days of recorded conversations, we walked at dusk amid the ancient forests of Douglas fir or examined salmon redds along the banks of the McKenzie. We were mostly silent on those excursions, talked-out from the interviews, allowing our thoughts to drift in the gloaming. On one of those walks, Barry asked about my own life, the things that mattered to me, the books I wanted to write. I told him how his work had given me a level of clarity about a difficult three-year period in my own childhood. When I was ten years old, my parents moved our family to Nigeria so they could volunteer as medical missionaries, and I was sent to a mission boarding school. I never experienced sexual abuse, as Barry had, but living in the absence of parental love during such a formative time in a child’s life took its toll. I knew I wanted to write about those years. I also worried that my experience was too specific to me. Barry helped me to see that if I could write that story, it could be of service to others who were struggling to find a way through their own pain.

As we walked through the woods, he was quiet for a moment, considering. He recalled a line from the Gospel of Thomas, and when he spoke, I felt it coming from the depths of his own struggle, his words and the words of the ancient text offered up as both gift and challenge. “If you bring forth what is within you, what you bring forth will save you. If you do not bring forth what is within you, what you do not bring forth will destroy you.”

We writers are given our yearning, and our wounds, for a reason, I understood Barry to mean. Our task is to write a story that will be of service, to write from a place of moral responsibility. We must attend to that yearning, or it will destroy us.

In his final book, Horizon, Barry gave us language that limns our uncertain future as we face the effects of climate change, what he called “this throttled earth.” The beauty and clarity of language in that book works in counterpoint to the multiple threats—droughts, melting ice caps, increased wildfires—it describes. The language elevates rather than suppresses our desire to face the dark horizon, to try to ameliorate our situation. In the final months of Barry’s life, that future arrived at his door.

On the evening of September 7, 2020, a fire started roughly ten miles upriver from Barry and Debra’s home. High winds had snapped a tension wire and ignited dry grass. With winds gusting up to 40 mph, the fire was off and running. “It was a climate fire,” Barry told me. “It came from the east, and the east winds down the canyon caught us by surprise. Normally weather comes from the west.” They awoke at 1 a.m. on September 8 with firefighters banging on their door. Barry walked outside in his bedroom slippers and down vest. “The ridges all around us, horizon to horizon, were aflame. The roar of the fire was unmistakable,” he told me.

Barry and Debra drove into Eugene, where they sheltered in a hotel. A few days later, they got word that their house was still standing, but as Barry told me, “We took no relief, because those were words from people who didn’t know the difference between a house and a home.” When they returned, they found that the house stood, but the forest of firs was decimated. Worst of all, the shed where Barry had stored his archives—the first eighty volumes of his journal, which he wrote in nearly every day over the past fifty-four years, artwork from his books, gifts from friends and readers, boxes of correspondence—all of it was gone, ash. The only thing left was a set of steel steps anchored to a concrete pad. His life’s work, along with the forests of his beloved McKenzie River valley, had become throttled earth.

“When the archive burned,” Barry told me, “fifty-four years of life burned with it. I felt like I’d been erased.”

He and Debra had become climate refugees. Three months later, Barry started hospice care.

In our last conversation, Barry told me how two weeks after the fire, he walked the land with an old friend, a nurseryman from California. A bracken fern, already two inches tall, pushed up through the black debris. They collected mother stock from Douglas fir, wild ginger, inside-out flower, pig-a-back plant, redwood sorrel. The friend planted the propagules, and by December had two greenhouse benches full of mother stock reclaimed from the ashes. Barry was looking ahead to summer. “We’ll gather some people together and plant. We’ll plant trees and shrubs and grasses and forbs,” he said. He wanted to restore the place that had shaped the cells of his body, even as those cells were dying.

After he told me the story about his visit to Gethsemani, when he considered becoming a monk, he paused for a long moment, inhaled deeply, and said: “The point of a life—at some moment in the evolution of that life—has got to deal with the question of service. I have become a kind of vessel for a set of ideas about how to conduct your life.” Barry’s path led away from the nest, out to the remote corners of our world, and into the dark corners of the human psyche. His service lay in his ability to find stories that might heal, that might show us a way out of our predicament.

“You have to find a metaphor,” he said, “and when you feel the surge of life, you’re in the right place.”

First published in Notre Dame Magazine.

Horizons

Barry Lopez, a celebrated author who detailed moral and natural landscapes in our imagination for decades, died peacefully in Oregon on Christmas Day, 2020. This film is a tribute to his life and work. Through archival footage and an interview conducted shortly before his death, Barry shares what drove him toward new horizons so that he might help our culture find balance with the living earth.