Charles Foster is a writer, barrister, and a Fellow of Green Templeton College, University of Oxford. He is the author of more than twenty books, including Being a Beast: Adventures Across the Species Divide, The Sacred Journey: The Ancient Practices, and Wired for God: The Biology of Spiritual Experience. His most recent book is Cry of the Wild: Eight Animals Under Siege.

Daniel Liévano is an editorial illustrator and author based in Bogotá, Colombia. He is deeply inspired by semiotics, linguistics, and the meaning of language. Notable clients include The New Yorker, Harpers, The Atlantic, Penguin Random House, and Radioambulante. He won a Gold Medal from The Society of Illustrators for his first graphic novel, Gravity, and the AOI World Illustration Award for the animated illustration accompanying “When the Earth Started to Sing” for Emergence Magazine.

As a writer seeking to experience and express communion with the more-than-human world, Charles Foster begins to wonder if language can do anything other than constrain and tame the tangled wild.

I’m losing confidence in words.1

This is worrying. On many levels. The least significant is that I use words to earn my living. The two most significant are, first, that I use words to tell my children I love them, and, second, that my whole experience of the world is mediated through words. I’ve a vertiginous fear that if words prove untrustworthy, I won’t be able to know anything about anything. And isn’t some sort of knowledge needed for relationship—which is all we have?

This is my own crisis. I don’t expect any sympathy. But one small corollary might be interesting. That’s the issue of whether any nature writing is valuable.

There’s a wood near us. I can’t see the wood for the words. Probably the wood is wonderful. My intuition tells me it is. But unless intuition is knowledge, I really don’t know. And even if intuition is knowledge, all that I get from my intuition is the generic assertion, “This wood is wonderful.” I can’t see any particulars. I can’t get an uninterrupted view of a flower petal or the hair on a caterpillar’s back. My words about petals and caterpillar hairs get in the way. I am appalled by the distance between a petal and the word “petal”: by the dissonance between the word “hair” and a hair—let alone between the word “hair” and the hair. When I think I’ve described a wood, I’m really describing the creaking architecture of my own mind.

The poets—the cruel, correct bloody poets—tell me that all the real wonder is in the shimmering particularity: that if I generalize, abstract, or philosophize, I’ve lost the plot, missed the point, and I am wasting my life. “Philosophy will clip an Angel’s wings,” wrote Keats; “Conquer all mysteries by rule and line, / Empty the haunted air…”2 I don’t doubt him. And if abstract musing, and the words designed for that musing, do that to an angel’s wings, just think what they must do to the much smaller, more fragile wings of a goldfinch.

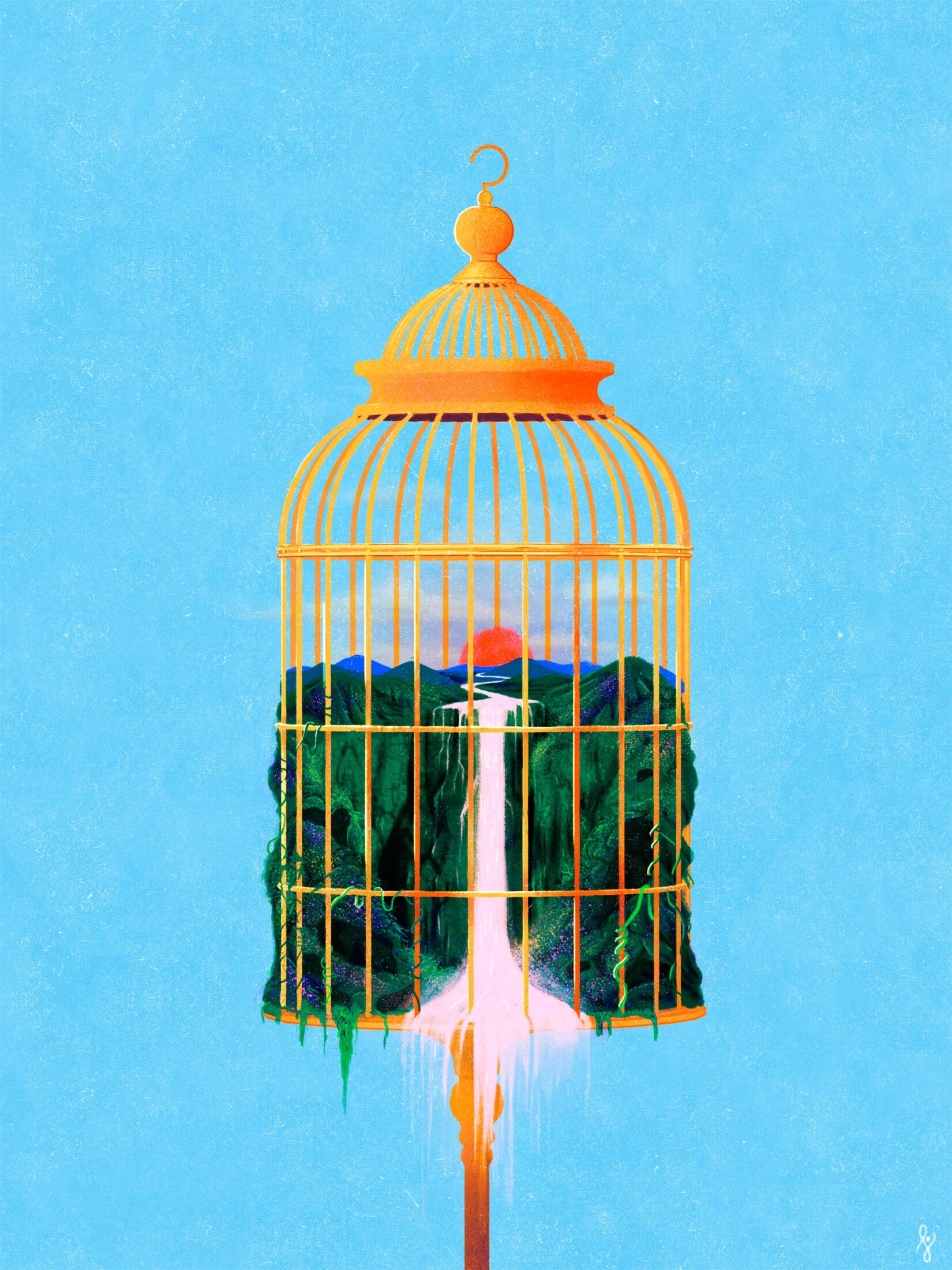

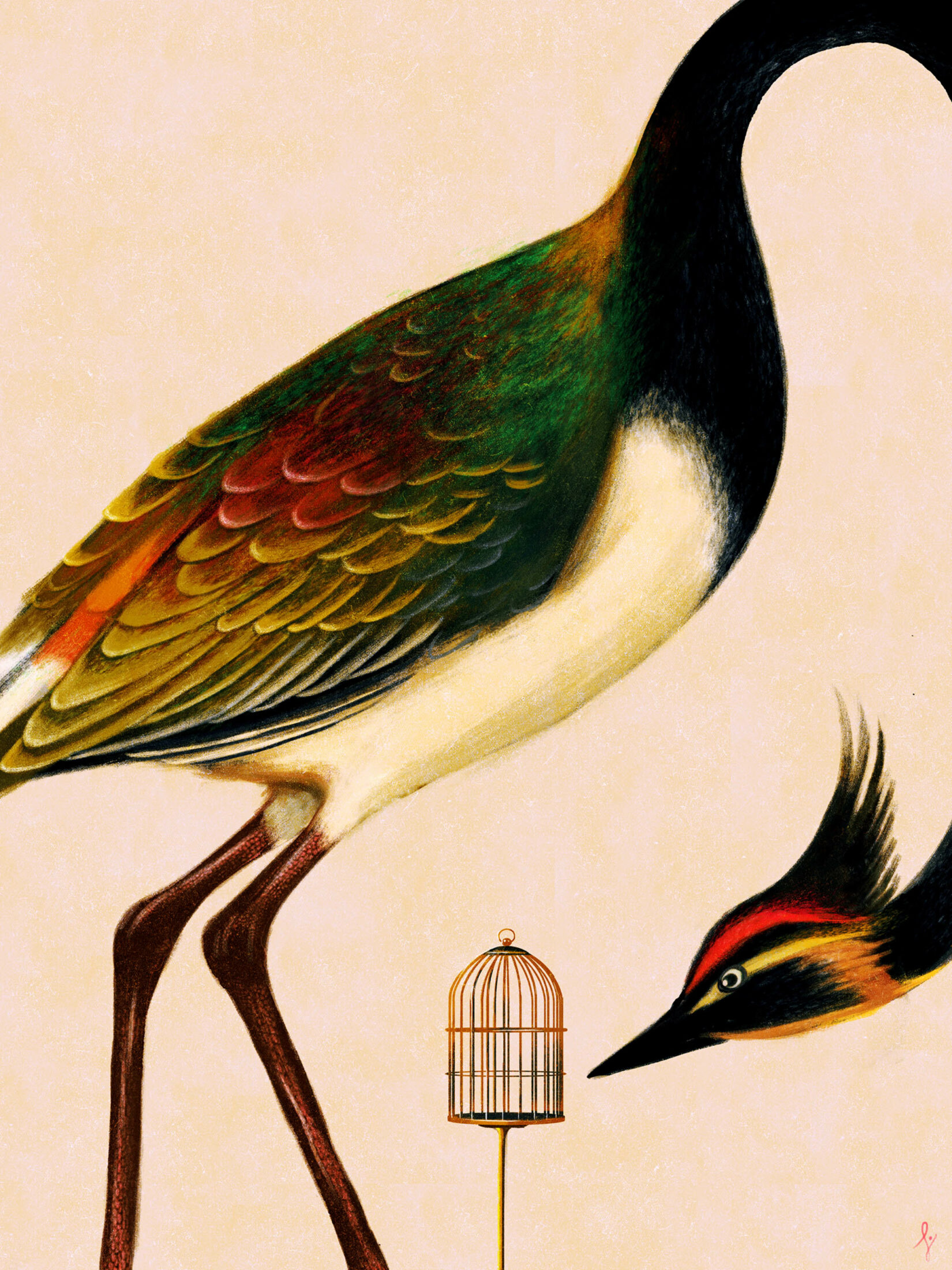

My own words might be particularly clumsy and obstructive; they might be unusually riddled with the pathology of abstraction; they might obscure even the outline of a rabbit’s ears or the belly of a mountain far more than your words. My metaphors might be extended beyond breaking point, my similes narcissistically self-referential. But surely at least some of the problem is with language itself. Much of it proceeds from the left cerebral hemisphere—the hemisphere that controls the grasping, controlling right hand. Language wants to clutch, corral, and fence; to constrain, tame, and neaten the tangled wild. And that makes the tangled wild mad as a caged wolverine. It won’t fit inside our categories; it tramples down our fences. Footless amoeba leap over them. Gigantic mountains creep through the invisible gaps between the bars. We don’t like that. We like our fences. They make us feel secure. And so, what do we do? We give up the impossible job of trying to keep the real live wild inside our linguistic zoo, and instead exhibit pictures of the wild that we have painted ourselves; pictures that, like most human pictures, are really of ourselves. At least that’s what I do.

“All names fall short of the shining of things,” wrote Andrew Harvey.3 To talk about mountains—to talk even about a squirt of bird shit—is to parody and misrepresent them sacrilegiously. It is a process of re-creating them in our own image. We don’t hear the wind at the summit ridge; we hear our own voice. We don’t smell the moth wings and digestive juice in the bird shit; we smell our own deodorized armpit.

If we earn money by writing about the natural world (as I do), this is bad news. I’m a fraud. “Roll up, roll up,” I shout. “Come and see the tiger. Just $15 a peep.” But when I’ve pocketed the $15 and ushered the public inside the covers of the book, there’s no tiger to be seen—just a cack-handed portrait of me.

What’s to be done?

It’s a scary question. The next few paragraphs will decide whether there’s an honest way to pay my mortgage.

I suppose there are three possible responses.

The first is to try to throw language away and strive for the direct, unmediated experience of reality spoken of by the mystics—perhaps with the help of drugs, meditation, cold-water swimming, or dancing round a campfire until the blood spurts from the ruptured capillaries in my nostrils.

That would be financially ruinous. The logic of the strategy would mean that if I had an epiphanic encounter with the Ground of Being incarnate in, say, a badger’s body, the encounter would be, by definition, beyond words, making it useless for the purpose of the mortgage.

Throwing language away is also, of course, much easier said (geddit?) than done. It might need a lot more than an industrial dose of mescaline or a shivering winter in a Himalayan monastery. It might need thousands of dreary incarnations—possibly as beetles, wood lice, or petroleum executives—to rinse the language out of you. And beware: language is a boomerang. Throw it away and it’ll come straight back and smash your teeth.

The second response is to shrug, say that our cognition and our language are so inextricably entangled that we just have to live with the entanglement, and (if we want to be honest) admit that our tiger pictures, as opposed to real tigers, are what are on offer, and suggest as humbly as possible that those pictures might nonetheless be worth viewing.

The third response is to acknowledge that we can’t free ourselves from language—that language is part of the web and weave of human perception and understanding—and try to use language in a way that subverts its colonial tendencies.

I badly want this third way to be possible. I want it so that I can carry on earning a living and talking to my friends. I want it so that I need not despair of brokering some relationship with reality. I want it so that I can hope to share something of the joy and pain of that relationship with others. I need language for the sharing (I suspect), and there’s no frustration like the frustration of an epiphany that cannot be described; no loneliness like that of a widow who can’t say that her husband is dead.

There are some things we can do. We can show deference to the natural world by imitating it in our stammering cadences: by listening carefully to its accents and striving to reproduce them in onomatopoeia. The leaves in our essays should rustle. Chiffchaffs should flit through the woods. Swifts should screeeeeeeam. Rain should hissssssssssss. Boughs should creeeeeeeeak.

“Show, don’t tell,” all novice writers are told. It’s important advice, but it overstresses the eyes. That’s a mistake—not least because our vision and our cognition are tied tightly together, and so, to invite visualization directly is to invite our own abstractions to muscle in and elbow out the real deer or the real wave—replacing them with our anemic, generic, and downright inaccurate ideas about deer and waves. We’re so used to doing it that we don’t notice it’s happening. We thoughtlessly equate sight with understanding. “I see,” we say, when we really mean “I understand.”

Language wants to clutch, corral, and fence; to constrain, tame, and neaten the tangled wild.

Other sensory modalities are less invested in abstraction. Take hearing. I can hear something without immediately translating the sound into my own visually generated thoughts.4 The life and power of music are not dependent on any visual images they conjure. Much less is lost and distorted in the translation from reality to sound than in the translation from reality to vision.

So I want to modify the advice to writers: “Don’t tell,” it should go. “Make us hear it.”

Avoid metaphors and similes; nothing in the universe is sufficiently like anything else. No metaphors are useful except to show that we’re smart. All similes are misleadingly inaccurate or patronizing or both.

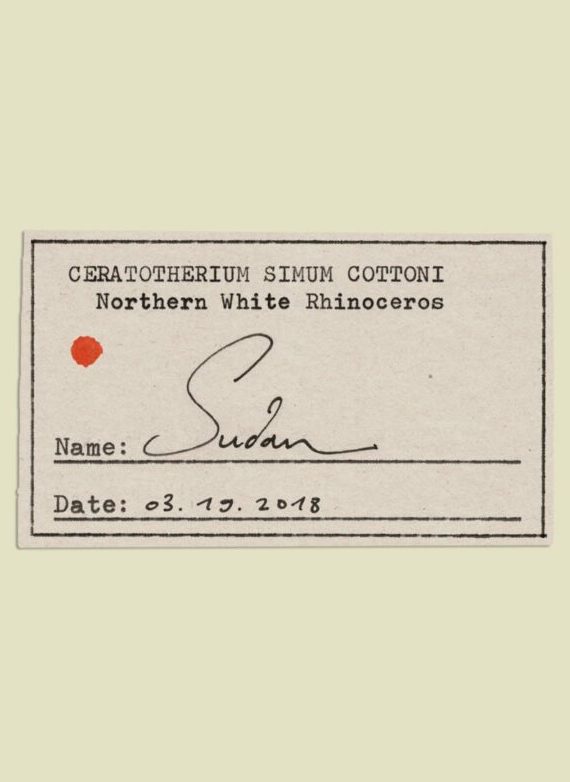

Be unapologetically but cannily anthropomorphic. Anthropomorphism is unpopular. It must be rehabilitated.5 It’s not only an expression of the vast amount of physiology and evolutionary history we share with nonhumans, but also an acknowledgment that consciousness is everywhere. We should pray for the eyes to see it and the humility to look for it. We can reasonably infer personhood where there is consciousness, and it is morally mandatory to do so. So personhood is everywhere too. Denigration and dehumanization are central to the colonial project of writing and abstracting (and striding and conquering and penetrating). Fight back by humanizing. Decolonialize writing by assuming that the dignity of the natural world is the dignity of personhood, and imitate the voices of the wild persons snuffling round the shed or soaring over the roof. Let the sea-person mutter, the tree-person whisssssssper, and the mountaintop-person howwwwwwwl.

Adjectives and adverbs are about us and our experiences and comparisons. There are many hypocritical examples in this article (as there are of similes and metaphors). Stamp them out so that the world outside our head can be heard. Use short, blunt, direct, Germanic words rather than artful, mellifluous words with roots in the Romance languages. The Romance words carry too much freight; they’re too encrusted with the patina of human cultural use. They’re weaselly. They have footnotes and learned genealogies. And so, perhaps ironically and perhaps not, they are less effective vehicles for the paradox that, as Alan Garner points out, is at the heart of all worthwhile writing because it is at the mysterious heart of all reality. “Romance is rodent,” he writes, “nibbled on the lips. Germanic is resonant, from the belly. It is also simple, and, through its simplicity, ambivalent: once more the paradox.”6 Hence, no doubt, the peculiar power of oral as opposed to written traditions of exposition and story.

Vowels, Garner contends, represent emotion, and consonants thought. I see what he means. “O!”—which appears as a breathless exclamation in much of the best poetry and prose of the Romantic movement—is the real response to the wonder of whatever is being beheld: the bulk of the text is just more or less cumbersome, obfuscating commentary on the “O!” The “O!” is often used ambiguously—both as an epiphanic gasp and as a mode of addressing the world (“O bird…”)—which means that personhood is assumed, invoked, and honored: there’s a stuttering, respectful attempt to establish a conversation. “Aaaaaargh” rasps straight out of a terrified throat before any fancy adjective can qualify it or blunt the edge of the fear. We utter vowels when we’re relating directly. “Aaaah!” is the sound we make when we really understand something—when shallow, tawdry comprehension joins with mature, poised apprehension to form proper knowledge. “Ooooo!” is often the first, prelinguistic sound made by the human child. It’s accompanied by a delighted pointing. When there is wonder and you’re not embarrassed to admit it, you say, “Ooooo!” These sounds are followed inevitably by an exclamation mark, for everything worth vocalizing about is surprising. Reality is an unbroken stream of surprises, coming too fast for us to notice anything other than the odd one, until we become mystics and learn to live in the stream.

And now that I notice it, the defining belly sounds of the nonhuman world are mainly vowels. I should have written Chiffchaff as Chiiiiiiffchaaaaaff. Those swifts truly do screeeeeeeeam. The rain hiiiiiiiiiiiiiiises far more than it hisssssssssssses. Birds really do tweeeeeeet. Except when they cooooo, whoooooop, hoooooot, or kraaaaaak. In each case the consonants are just bookends—nothing to do with the substance of the sound.

Consonants serve a mean, functional, workaday purpose. They are good for the transmission of information: think of the clicks of dolphins or echolocating bats, or the neatly tenoned sentences of scheming crows. But you can have all the data in the world and still understand nothing at all. You can have all the information about a hedgehog and know nothing about it. In fact, I’m tempted to say that the more information you have, the less you really know.7

Vowels are the guts and balls and throat of Germanic words, and hint well at the guts and balls and throats of gannets.

And then there’s story. Life-changing writing—even if it’s arid academic writing, couched in syllogisms—is necessarily storytelling. This, I think, is because everything and every thing, like a story, has a beginning, a middle, and an end. Every person is process. Time, which processes, is the only medium in which we and anything of which we can know can float, and stories bob up and down very obviously in time. Stories alone enthrall and convince us because we are stories and understand nothing that is not also a story. Garner again: “The universe presents itself as a Mystery. We have to find parables, we have to tell stories to unriddle the world.”8

It is a good thing to write about action—for action and abstraction are deadly enemies, but action and story are close cousins, and action and process are even closer. Adverb- and adjective-free action stories in crude, rude words with lots of vowels; lots of furry, feathered, leafy people; and no rumination: that’s the way forward.

But all this is really about making the best of an epistemologically bad job. It describes how we should write if we really have to. But must we? Is there any excuse for writing—let alone any obligation?

A good excuse and any kind of obligation would both depend on some fundamental concordance between language and reality—at a level far deeper than onomatopoeic imitation.

Some think that, at least so far as alphabetic writing is concerned, there is no such concordance. David Abram is the obvious example.9 Indeed, he goes further, holding that the advent of alphabetic writing marked an important breach between the human, alphabetic-linguistic world and the nonalphabetic, nonhuman world. Since (his thesis goes) it was assumed that the only real languages were alphabetic ones, and nonhumans clearly didn’t have those, they were deemed to have no language at all. So the wild chattering world, whose whole essence is connection and vibrant communication, was written off (often literally) as dumb, deaf, and dim.

This, thinks Abram, is peculiarly or particularly a characteristic of alphabetic writing, because words composed of alphabetic syllables convey sense only when the syllables are given meaning by a human brain. Pictographic writing, which nods explicitly to the nonhuman world, does not depend entirely on ingenious human abstraction: in a pictographic language, a written tree looks rather like a tree.

This feels right to me, but I’m not ready to give up on my kind of writing just yet.

There are glimmers of hope. There’s Noam Chomsky, for instance, who posits that a facility for language lies latent in the growing heads of young humans and is easily triggered into an exuberant capacity for expression. There’s a monumental disproportion, he says, between the triggering events and the result.10 If he’s right, it might imply that human language is not purely human: that a human child learns the word “crow” ridiculously easily because the word “crow” is truly, deeply, nonarbitrarily connected with cunning black birds.

But this is too complex and slender an argument for comfort. It doesn’t feel as if it is up to the strenuous job of justifying my existence.

More promising are some ancient and hallowed hints.

In the Hebrew tradition, God spoke and the world sprang into being. Not just the world as a whole, but the individual things within it. Words were used to differentiate, to individuate, to distinguish between the sea and dry land, and between light and darkness. There is an early and emphatic connection between specific words and the existence of specific things.

It’s not just God’s words that have that fundamental connection. God delegated to humans the process by which fundamental connections are forged between words and the natural world. For in the second of the two Creation accounts in Genesis, Adam gave to each animal the name that distinguished it from all others.11

There is more from the Hebrew tradition.

The Hebrew holy name—the tetragrammaton—consists of four consonants, יהוה: yod, heh, vav, heh. It is commonly rendered as “Yahweh,” but we have no idea if that’s right, and we’re much safer not knowing. Vowels aren’t used in the written text of the Torah, and of course words can’t be pronounced without vowels. The pronunciation of any word in biblical Hebrew thus depends on knowledge that comes from outside the text itself, which suggests a more intimate relationship with the thing represented by the word than we generally suppose. The thing itself decrees its own name and meaning and rendering. The ultimate example of an unpronounceable Hebrew word is the tetragrammaton. Only the high priest of the Jerusalem Temple knew the correct rendition, and he uttered it only on Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement.

The Name wasn’t involved only in Atonement. In many kabbalistic formulations, it was the Name itself that kindled Creation.12 God’s Name was his essence, and so the creating word was the source, the sustainer, and the essence of everything that proceeded from him. Things were made by the Name and were inherent in it, taking its name and its nature, and then by a process of delegation whose authority derives from the Divine Name, names given by humans were and are substituted. Because humans are themselves made in God’s image, these new names retain the fundamental connection with the things named that the originating Divine Name had. When I’m at my laptop, I’m a modern Adam, renaming the animals. The new names will be more or less consonant with the real nature of the beasts, depending on the synergy between the divine sparks flickering in me and the divine sparks flickering in the beasts.

The leaves in our essays should rustle. Chiffchaffs should flit through the woods. Swifts should screeeeeeeam.

In the first Creation story, the Earth was “unformed and void,” and there was “darkness over the surface of the deep.” There swept over these forbidding waters “a wind from God.” This “wind” (which can also be translated as “spirit”) seems to be coming from God’s throat, for it is mentioned immediately before God begins to speak and, by speaking, to create.13 His spirit—his nature—from which all creation derives and which is reflected in the nature of the whole creation, is a breath: it’s audible; it’s the first recorded instance of the oral tradition of creativity. If the kabbalists are right, the word that started it all is “Yahweh”—or something like that. But why those four consonants? asks David Abram. Because, he suggests, they are the ones that sound most like vowels. And why that combination of vowel-like sounds? Because that’s the combination that sounds most like the breath—whether the creating breath in God’s larynx or the subsidiary breath in ours. Speaking, then, has a divine mandate: it’s connected to the created. Vowels are particularly favored, I’m happy to note. Even the consonants are made to sound vowel-ish. Intuition triumphs over analysis. Data are put in their place. The oral tradition is sanctified. The written tradition can be, too, if it recognizes that it’s the younger, callow, dependent sibling.

I’m inspired by these reflections. They give me some hope for the general project of language use. But when I switch on my laptop, ear-gaze out of the window at the whiiiiiiiiiiisperiiiiing trees, start trawling through old notebooks, and begin the day’s work, my confidence ebbs. Genesis is too high and vaulting for me. Theology fails to comfort when I’m confronted with the many reasons to doubt the usefulness of human words.

There’s one final hope. It’s the product of a perhaps unlikely marriage between etymology and Rupert Sheldrake’s model of the presence of the past.

My beloved friend Jay Griffiths loves etymology. It suffuses much of her writing.14 She uses the genealogy of words to explore and expound their power over us—and to harness and magnify that power.

I have loudly and rudely questioned her about how she justifies this. And her gracious answer has always been to the effect, “It works.”

She’s right. It does. As she unearths etymological roots, they ignite, illuminating the whole word—showing us colors and contours that we’d never dreamt were there. The illuminated words make noises that we’d never heard before, and pump out smells that our noses have never met before, and (which is the point) look and sound and smell like the thing that they are trying to describe. Yes, even the smells look and sound like the thing, because she’s a great writer who can make us synesthetic. If her words can do that, perhaps I’ve underestimated language.

Why this weird ignition? Not, for sure, because the disinterred root reminds me of something I knew before—something interred in my own subconscious—causing me to confuse the excitement of recollection with the experience of honest description. Jay’s etymologized badger is palpably, eerily close to a grunting, snapping thing with a striped face—and far closer than a nonetymologized badger.

This is almost exactly the opposite of what I said earlier. It’s embarrassing. I said then that the patina words acquire by being handled constantly by humans makes those words—however honest, accurate, and deferential to the real world they were when they were coined—incurably artificial, hubristic, and self-referential. Now I hear myself saying that to track the origins of words deep into their very human history can make them behave more honestly—can make them reflect more reliably the things in the nonhuman world to which they purport to refer.

That’s strange. Perhaps Sheldrake can help? The universe forms habits, he thinks.15 Once a compound crystallizes in Sydney, it will do so more easily in New York. When rats learn a particular trick in Berkeley, they will learn it faster in Delhi. We grow closer together by acting together. By the same token, might words about X, used seriously and repeatedly, not come truly to be like X? To resonate with it? To give off the same vibrations that it does?

The immutability of the icon-painting conventions in the Eastern Orthodox Church means that the face of Saint John the Theologian is truly invoked by the successive painters, however unanatomical the representation. Saint John looked like that—was truly that—in first-century Palestine because he was consistently represented that way in following centuries. The equally conservative prayers approximate ever more reliably to the truths about God because they have been uttered faithfully and with shared understanding by millions over millennia. When I join with the millions in agreement about the meaning of a word, there is less of me engaged; there’s less of the self-reference and self-reverence that I’ve denounced in writing about the dangers of language.

Now, here comes the big step: if words, in principle, can say true things about God, it’s perhaps not so ludicrous to think that they can say true things about badgers.

This doesn’t contradict what I said about rough, short, Germanic words. They’ve been used more than long, fancy ones, and because they’re less ambiguous, they have been used with genuinely shared understanding of whatever it is they’re purporting to represent.

Now I see, too, that I need to distinguish between words and language. It is words that are assumed to stand proxy so reliably for things in the world that they become those things—nouns, primarily, but also actions: “John,” “crucified,” “worm,” “teeth,” “chomp,” “piss.” It’s words that get encrusted with that resonating patina—the patina that expounds, deepens, and clarifies and does not obscure; that emerges from a consensus and, so, points to the thing described rather than back at the narcissistic author. The narcissism comes in the artful combinations: the sleek syntax, the intrusion of personal impression.

Poetry can show the way. By allowing words to stand for themselves, poetry can escape many of the charges I’ve leveled against language by using language against itself: by subverting language. If we let words do that, they never stand for long; they fizz and spark like Roman candles, and set on fire all the words around them until the display looks like nothing the poet could ever have devised.

The ancient words of the Orthodox liturgy, or the Om mani padme hum, or the Upanishads, have an incantatory power—a power of invoking that which they seek to invoke—because they have been repeatedly uttered. But they have been repeatedly uttered because millions have trusted them. To take etymology really seriously is to trust words.

And perhaps that’s what it’s all about. In my less depressive moments, I think that there’s a deep and universal principle at work—which is that if you really, really trust the world (a world that includes words) and make yourself wholly vulnerable in the event of your trust being misplaced, the world always honors and rewards the trust and the vulnerability. You can call it faith or grace if you want.

If nature writing can be defended, that, it seems to me, is how it has to be done.

I believe in the defense about 49 percent of the time. I’m a dishonest man for the rest. On balance I’m against nature writing.

- I’m not the only one. Many of the people I like, from Wittgenstein to Paul Kingsnorth (see Kingsnorth’s Savage Gods, Little Toller, 2019), have a similar distrust.

- From the poem “Lamia,” by John Keats (1820).

- Andrew Harvey, A Journey in Ladakh (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1983), 93.

- Scent, being less confident than hearing, gives way too readily to vision.

- Anthropomorphism, as Carl Safina observes, is a good first guess as to what a nonhuman is feeling: see Carl Safina, Beyond Words: What Animals Think and Feel (New York: Henry Holt, 2015).

- Alan Garner, “Achilles in Altjira,” in The Voice That Thunders (London: Harvill, 1997), 45.

- Thoreau agreed: “I do not get nearer by a hair’s breadth to any natural object so long as I presume that I have an introduction to it from some learned man. To conceive of it with a total apprehension I must for the thousandth time approach it as something totally strange. If you would make acquaintance with the ferns you must forget your botany. You must get rid of what is commonly called knowledge of them. Not a single scientific term or distinction is the least to the purpose, for you would fain perceive something, and you must approach the object totally unprejudiced. You must be aware that no thing is what you have taken it to be. In what book is this world and its beauty described? Who has plotted the steps toward the discovery of beauty? You have got to be in a different state from common. Your greatest success will be simply to perceive that such things are, and you will have no communication to make to the Royal Society.” Journal XII, October 4, 1859.

- Garner, “Achilles in Altjira,” 56.

- David Abram, The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-Than-Human World (Vintage, 1997).

- For example in Knowledge of Language: Its Nature, Origin, and Use (Westport: Praeger, 1986).

- Gen. 2:19–20 (Jewish Study Bible).

- In 138 Openings of Wisdom, Rabbi Moshe Chaim Luzzatto says, “In sum, all that exists is founded on the mystery of this Name and upon the mystery of these letters of which it consists. This means that all the different orders and laws are all drawn after and come under the order of these four letters. This is not one particular pathway but rather the general path, which includes everything that exists in the Sefirot in all their details and which brings everything under its order.” 138 Openings of Wisdom, trans. Rabbi Avraham Greenbaum (Jerusalem: Azamra Institute, 2005), opening 31.

- Gen. 1:1–2.

- See, for instance, Wild: An Elemental Journey (New York: Penguin, 2008).

- For example, in The Presence of the Past: Morphic Resonance and the Habits of Nature (London: Icon, 1988).

On the Language of the Deep Blue

In an effort to redeem the self-referential, reductionist nature of human language, Charles Foster travels to the Isle of Skye seeking out a language beyond the human in the vibrant and vast communication of the eight remaining Scottish killer whales.