Nicholas Triolo is a writer, filmmaker, photographer, activist, and long-distance trail runner. His writing, films, and photography have been featured in Orion, Outside, The Dark Mountain Project, Terrain.org, Trail Runner, and elsewhere. He has directed two documentary films, The Crossing and Shaped by Fire, and collaborated on a film about touring and training Death Cab for Cutie frontman Ben Gibbard. Nicholas’s films have screened at several international film festivals and have been featured on platforms such as Patagonia’s Dirtbag Diaries, Upworthy, and Outside magazine. His forthcoming book is The Way Around: A Field Guide to Going Nowhere.

With a book of Thomas Merton’s writings in his pack, Nicholas Triolo walks the length of Portugal’s Rio Côa in search of what it means to rewild land and ourselves in a time of ecological collapse and despair.

Cornered in THE PLAZA of a small town in central Portugal stands an Iberian lynx, one of the most endangered cats on Earth. The sun sets after a heatwave in May, but this feline doesn’t move. In fact, the cat is a twenty-foot sculpture of bone-white plaster built next to a river, the Rio Côa—no one has seen a real lynx here for twenty years.

A scrum of teen girls takes selfies in front of the two-story myth before admiring the artist’s bipolar rendering: lower half fractal, upper half feral. While its hindquarter cuts in triangles and pixels, the shoulder blades and head are all sinew and riotous hair, as if the animal were disrobing some straitjacket and crawling home after a long slumber.

Sabugal is a municipality in east-central Portugal, a two-hour drive inland from the Atlantic, home to twelve thousand residents and one oversized cat. Between the Algarve to the south, Lisbon and Porto to the west, and the Camino de Santiago to the north—itself seeing half a million pilgrims annually—this town is off any tourist map, spun to the axis of a Gothic castle built in the thirteenth century where a forgotten battle combusted between British and French imperial powers. Some visit for the natural thermal baths.

Few come, as I have, for the lynx.

In 2016, Rewilding Europe identified the 120-mile Côa Valley as one of the world’s most promising rewilding ecosystems, prime habitat for endangered species like the Iberian lynx, Iberian wolf, and griffon vulture. I’d been following their developments for several years and grew fixated on what rewilding felt like during these initial phases.

The plan was simple: I’d follow old roads and footpaths along the full length of the Côa over five days, starting at the headwaters along the Spanish border and ending in Vila Nova de Foz Côa, where the river drains into the Douro. What, I wondered, might emerge from a river that had become overused by agriculture and whose residents had largely abandoned the region in favor of city life? “Rewilding” was a sexy word, sure, but what did it actually mean? What does rewilding look like in the face of intractable trends such as runaway AI automation, the rise of far-right nationalism, and unhinged climate disruption? What’s the texture of rewilding projects amid growing inertia toward a sixth mass extinction event?

Day One: Fóios to Sabugal

A white Peugeot sedan weaves pre-dawn through foothill hamlets. Following a family reunion in Lisbon, my father volunteered to drop me at the Côa’s source east of Sabugal. After winding up to four thousand feet, Dad shuts off the engine. From here, everything will dilate: the breadth and depth of this watershed, the triple-digit heat to come. At the crest of this interlocal border pokes a sign written in blood-red: COA. Nothing stirs, only blushing fields of broom, native yellow-flowering evergreens. A spring gurgles from a stone altar as we stand and listen to the sound of a river’s birth. I cup my hands for a sip. From here one can see fifty miles in every direction. Mud squishes below our feet, nothing like the full body this water will soon become. To stand at the start of a river feels like a promise, especially as I watch my aging father struggle to take an iPhone photo with frozen fingers. The rising day, a crowning river, a mortal parent—all of it invites a ceremonial here-ness.

Rivers are so much larger than rivers, I think.

They’re conductors, vaulting from some never-knowable heart chamber.

And this spring, this is where blood comes from.

Photo by Juan Carlos Muñoz

Courtesy of Rewilding Portugal

After my father departs, I cinch up my pack: bivy sleep system, nuts and bars and unusual Portuguese gummies, two pairs of shorts, a shirt, a pocket Moleskine. I was aiming to go light and yet somehow neglected to offload the heaviest item, the 445-page Asian Journal of Thomas Merton. Published posthumously in 1973, the Journal is a series of fifty entries from the Trappist monk’s travels through India, Sri Lanka, and Thailand in the fall of 1968. These dispatches are raw—scraps of thought, quotes from readings, rambling endnotes—an unedited look into the mind of a countercultural mystic at the height of his spiritual inquiry.

Merton, born in France to a pair of artists in 1915, was raised in New York City, later studying literature at Columbia University. He loved jazz and longed for the avant-garde, until discovering a deeper passion for God. On December 10, 1941, he decided to move to a small town in Kentucky to become a monk and priest at the Abbey of Gethsemani. December 10 proved significant for him when, on the same date in 1968, he would be found dead in Bangkok. Around 4 p.m., colleagues walked into his room to find Merton half-naked and motionless, blood coming from his head, an electric fan atop his body, and a burn down his right flank. Thai authorities identified the death as an accidental electrocution, though many called foul play. To this day, it’s never been solved.

Earlier that morning, at an event organized by French Benedictines, Merton had delivered a speech on Marxism and monastics, which was received poorly. A self-identified anarchist, Merton was outspoken for his social and environmental activism, and, at times, a scathing critic of the Church. He drew inspiration from cultural icons like Rachel Carson, Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, and Allen Ginsberg. By 1968, the Vietnam War had spun out of control and several thousand CIA operatives were crawling Southeast Asia with directives to prune any anti-war detractors. “Tom was becoming a serious threat to the policies of the U.S. government,” a friend noted in the Catholic Review.

“I come as a pilgrim who is anxious to obtain not just information,” the fifty-three-year-old monk remarked at the beginning of his travels in a lecture in Calcutta, “not just ‘facts’ about other monastic traditions, but to drink from ancient sources of monastic vision and experience.” The pilgrimage felt to him like “a great sense of destiny, of being at last on my true way after years of waiting and wondering and fooling around.” He then adds, hauntingly:

“May I not come back without having settled the great affair.”

As I stand at the top of the Côa, Merton sits at the bottom of my pack. Coaxed by the ghost of an elusive wildcat, I will also be haunted by Merton’s writing and spiritual traverse of the human heart, a heart taken abruptly nearly sixty years ago. Following this watershed to its terminus, so too will I follow this anarchist-mystic’s life to the end through his writing—two rivers in conversation.

Photos by Nicholas Triolo

Early miles follow farm roads and stone-fenced pasture below wisped sky, while a triple-stack blaze of white, red, and yellow paint points the way—these markings will prove comically unreliable. A market sets up in Fóios at a pinch in the road: belts made of fresh leather, plastic dolls and toy pistols, hard cheeses and cured meats, jars of thistle honey.

Field Notes:

Two horses ying-yang in a field, tails swiping each other’s muzzles to deter flies.

Wild boar snarls nearby, the sound of a bear.

Four ears appear ahead. Lynx? No, a pair of red foxes.

Three gunshots.

Smells of carne waft along the path.

Family gathers in the shape of a horseshoe near a barn, drinking and grilling and shooting.

Children play. Red and yellow balloons bob everywhere.

Cow carcass rots beside a fire lookout, Alto da Machoca, 3,537 feet.

Whoosh of an industrial wind farm. Blades scissoring. White towers the size of skyscrapers.

Swallows above pull tricks.

This Grande Rota do Côa begins in Portugal’s most remote region and Rewilding Portugal’s southernmost range, passing along the eastern edge of the forty-thousand-acre Serra da Malcata Nature Reserve—established in 1981 to save the Iberian lynx. Strawberry tree, black oak, and cork oak thrive, though much was cut and replanted for industrial logging. This was also where, in 1992, researchers recorded the last sighting of Iberian lynx in Portugal. The subspecies inhabited the peninsula for over a million years; until the 1950s, thousands roamed free in Portugal and Spain, their range vast, with genetic remains found as far away as southern Italy. The following three decades proved catastrophic for the Iberian lynx, though, where they lost 80 percent of their former range. By 2002, the combination of habitat loss, poaching, and loss of prey resulted in fewer than a hundred adults.

Lynx feed mainly on rabbit and partridge. Once plentiful in Iberia, rabbits were decimated by a disease caused by myxoma, a virus introduced to France in 1952 to control their populations. Nearly all of the rabbits in France and the UK succumbed to the disease, which also spread to other parts of Europe, the single-most deadly vertebrate virus known to science, its own sort of wild. No rabbits, no lynx. Due to rigorous virus mitigation, anti-poaching patrols, and habitat recovery, by 2024, Iberian lynx populations rebounded to over two thousand, considered “the greatest recovery of a cat species ever achieved through conservation.” Most of these gains, though, are tracked in southern Spain, and it may take years before the Iberian lynx returns here to the Côa Valley.

Covering thirty miles on the first day, I skirt along the shores of the Côa at dusk, now a reservoir. Shapeshifter: first a whisper at the headwaters, then a creek no wider than a school bus, and now, a lake. I wade into purpling water dissolved into a purple sky above. That night I work my way through Merton’s Journal, and it becomes clear why I brought the text along. Merton, too, was a shapeshifter: an artist and romantic in early life, then a devout Catholic, and finally, an interfaith activist hungry for truth. Of all Merton’s writings—and he wrote over fifty books during his life—I found his Asian Journal to be his most personal: a subversive Catholic leader on a collision course with Buddhist asceticism, like watching two rivers meet.

My obsession with Merton reflected a growing tension with how uncomfortable the word “God” made me feel and simultaneously how necessary it felt for me to somehow know God better during these destabilizing times. The modern-liberal inheritor of a congenital familial allergy to organized religion, I lugged around a closeted thirst for spirit, cosplaying as a Buddhist for years but secretly courting Christian voices who were pro-liberation and anti-capitalist, who centered justice and contemplation, who critiqued the Church’s shadow of empire—Meister Eckhart, Simone Weil, Richard Rohr, Thomas Merton—those intent not to burn the establishment to the ground but to salvage its essential parts. What I think I desired most was a source of renewable divinity that could orient me to the day’s polycrisis of dislocation and despair, runaway automation and climate spiral, a cultural hyperworship of the self. And this was how Merton remained in my pack: a crude but unavoidable curiosity for the unknowable.

What I think I desired most was a source of renewable divinity that could orient me to the day’s polycrisis of dislocation and despair.

Day Two: Sabugal to Miuzela

A body lies motionless in the middle of the path. I kick dirt to announce my arrival, but it’s not until I’m feet away that the man stirs. He dusts off his pants, calls to his sheep—a shepherd napping while his flock trims a meadow. At another curve in the road, a full-grown peregrine falcon flushes from the bush, speckled brown and white belly with yellow-black eyes so close they look like dinner plates, talons loud enough to meet my awe-thumping chest.

Field Notes:

Blue-tailed jay lands on the nub of a fence post, eyeing leftover pizza lashed to my pack.

Salmon-colored poppies riot.

Young couple thumbs seed into a humble plot of land. Man in a red-and-white-striped shirt, muck boots, a poorly rolled cigarette drooping in his mouth. Love never looked so good.

Donkey in a pasture surrounded by the puffed cream of Queen Anne’s lace.

Lime-green algae, archipelagos of phosphorous.

Fields of purple viper’s bugloss reach for pollinators.

Frogs waw-waw by a river bend, hundreds belching and zippering. Mating season.

Everyone’s excited to fuck, and why wouldn’t they be?

Two blisters on the outer left toe, a minor inconvenience.

Photos by Nicholas Triolo

“Rewilding” can summon visuals of large, unpeopled tracts of roaring forest, but this I know to be residue from a binary myth, that to rewild is to simply remove humans and let nature find itself. Here along the Côa, I find coexistence, human communities co-animating the landscape, reciprocity through generosity. Passing through Porto de Ovelha, I exit in search of a place to sleep in the bush before dark, but my task is interrupted by an elder couple walking along the cobbled streets, the only humans I’ve seen since my faux-corpse shepherd.

“Where are you headed?” the man asks.

“Foz Côa,” I say. “Following the river on foot for five days. From the birth to the death.”

“Well, you look like death,” his wife says, laughing. “Let’s get you some vinho and carne.” I follow them through a bead-draped doorway into a cottage holding ancient light, each stone wall insulated by stacks of books and family photos hung crooked. Zeida and Vitor are retired medical professionals: Zeida, a nurse, Vitor, a PTSD war psychiatrist. They live in Coimbra, near the coast, but come here to their family home along the Côa for solitude. The two fire questions in a mutt of English, Spanish, and Portuguese, and Zeida’s eyes sparkle when she speaks of her children. After walking fifty miles in two days, I’m red-eyed, sore, and now, half-drunk. Zeida disappears into the kitchen and returns with a bag of apples and bread for me, while Vitor sits at the head of the table looking one-quarter mafia, a cross between Robert De Niro and Sean Penn. I mention to him I’ll be sleeping outside tonight.

“Don’t be stupid,” says Vitor. “Wolves out there. Zeida reserved you a guest room in nearby Miuzela. We’ll drive you. After you finish your wine.” He glugs me up. As we pile into their car, I can’t metabolize the surprising generosity I’ve found so far along this route. Surprise is perhaps its own kind of rewilding. Settling into Miuzela at dusk, I meet more of Merton’s writing. Years before he arrived in Asia, the Trappist monk’s politics had begun to shift. His 1962 prose poem “Hagia Sofia” was perhaps Merton’s most lucid celebration of the divinity in the more-than-human world:

There is in all visible things an invisible fecundity, a dimmed light, a meek namelessness, a hidden wholeness. This mysterious Unity and Integrity is Wisdom, the Mother of all, Natura naturans. There is in all things an inexhaustible sweetness and purity, a silence that is a fount of action and joy. It rises up in wordless gentleness and flows out to me from the unseen roots of all created being, welcoming me tenderly, saluting me with indescribable humility.… I am awakened, I am born again at the voice of this my Sister, sent to me from the depths of the divine fecundity.

For Merton, Sophia was an omnipotent matriarchal presence shimmering inside everything, a fecund muse whispering from groves, birdsong, wind. This set fire to his love for the world and his outspoken works against injustice, to be highlighted in Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander. Merton’s letter to the marine biologist Rachel Carson in 1963 marked a major turn toward his more justice-inflected politics. In it he wrote that Silent Spring was an “essential piece of evidence for the diagnosis of the ills of our civilization.” He thought Carson had found a wellspring of concern in her work uncovering the ills pairing chemicals and industry, not only diagnosing the symptoms of mishandled power, but seeing such violation as an outgrowth of the sickness of society itself. Humanity had “lost his wisdom and his cosmic perspective.”

Merton would self-identify as an anarchist, mirroring his infatuation for the third-century Christian hermits who lived in the Egyptian desert. “[The Desert Fathers] were in a certain sense ‘anarchists,’ and it will do no harm to think of them in that light,” he writes in The Wisdom of the Desert. “They were men who did not believe in letting themselves be passively guided and ruled by a decadent state, and who believed that there was a way of getting along without slavish dependence on accepted, conventional values. But they did not intend to place themselves above society.” Through his notes and later works, I’d warmed to this kind of ecological devotion, Merton’s understanding that everything sung, everything was imbued with God’s divinity and, therefore, worthy of protection.

Photo by Ricardo Ferreira

Courtesy of Rewilding Portugal

I’d warmed to this kind of ecological devotion, Merton’s understanding that everything sung, everything was imbued with God’s divinity and, therefore, worthy of protection.

Day Three: Miuzela to Almeida

Louisa shells fava beans in a triangle of morning light. The matriarch of Miuzela wears a white apron over a flannel shirt, while her pepper hair thins at the scalp. We nip at short coffees. Last night in her bar, two shepherds shared their encounters with predators in the area. Between swills, a red-faced man told of catching a set of large eyes in the forest not long ago, near his flock. Wolves, yes, but no lynx.

Today, I’ll meet with Pedro Prata, director of Rewilding Portugal, to visit three of their main recovery sites: first to the herd of indigenous Sorraia horses, then a look at land art installations, and lastly, to a bird-watching station and reclaimed-mine-turned-aquaculture-experiment. Prata pulls up in a Land Rover and removes aviators to reveal committed eyes. A military-green cap sits atop black hair bunched in a ball, while binoculars hang on his shoulder. At forty-two, Prata looks more like a bassist for Portuguese hardcore than a PhD conservation biologist leading a multimillion-dollar rewilding enterprise.

After a short drive, we park and walk an unmarked dirt road where several wild horses cluster under the shade of an oak. “What we’re seeing here is one of the world’s rarest and most endangered horse breeds,” Prata tells me. In 1920, a Portuguese paleontologist discovered this horse breed at the confluence of the Sor and Raia rivers—Sorraia, one made from two. Their genetic origin remains unclear, but most agree they are descendants from the Eurasian steppe of Mongolia. Originally, Prata’s team introduced eight female horses and one stallion to the Côa. Fully domesticated, the male horse had never once eaten wild grass, never socialized with other horses, so when they introduced him to the females, he went crazy. They’re now trying to introduce more horses from different collectors to increase the genetic pool.

“So are these Sorraia considered wild then?” I ask.

“Their fully wild type is gone,” Prata says. “But it still lurks in there, that primitive instinct inside that allows them to fully express themselves. That’s exactly what we’re doing here.” Prata and his business partner, Sara Aliácar, founded Rewilding Portugal in 2019. After graduating with a degree in biology from the University of Lisbon, Prata threw himself into political organizing and became involved with Occupy Lisbon, while, yes, moonlighting in a straight-edge hardcore band. He eventually landed a job at a forest reinvestment fund—buying plantations to transform them into native forest—in nearby Guarda. A small nature NGO had started along the Côa and they were nominated to be the Western Iberia rewilding zone. A team leader position opened; Prata applied, was hired, and started in 2014. After some tough years of reorganizing and personal setbacks—his mother would lose a battle with cancer—Rewilding Europe invited Prata to rebuild the entire project from the ground up, which he accepted.

Following the Sorraia horses, we walk to an installation from the “Corridor of Arts,” a festival organized by his team in 2023 that featured land art along the river, paired with film screenings, local culinary pop-ups, and performances. Children, seniors, urban and rural families, those with disabilities, were all welcome. Four hundred artists participated, and the event attracted several thousand visitors to the region. “Public art and rewilding both rely on public dialogue for their development and success,” said visual artist Gaspard Combes, one of the festival’s artists in residence. They plan to offer it again in 2026.

We encircle one of the installations, a large structure made of stone and cork: imagine two earthen traffic cones the size of an SUV facing each other to make a natural, twenty-foot phonograph. Listen, the art seems to whisper. A prerequisite for all artists was that materials must be nontoxic and easily metabolized by the land. Decay aesthetics—another kind of rewilding.

Photo by Cláudio Noy

Courtesy of Rewilding Portugal

The modern rewilding movement was seeded in the 1960s, Prata explains, through research by biologists Michael Soulé, Reed Noss, and E.O. Wilson on ecological connectivity and habitat fragmentation for large carnivores. Earth First! (EF!), the anarchist environmental group from the American Southwest, would popularize the term “rewilding,” after launching the Wildlands Project in 1991, to hedge against extinction by promoting large habitat connectivity. Their slogan: Reconnect, Restore, Rewild.

According to the Global Rewilding Alliance, the main aim of rewilding is to mitigate species extinction through restoring ecosystem function with as little human intervention as possible. Rewilding focuses on three C’s: Cores, Corridors, and Carnivores. After establishing core nodes, islands of viable habitat, you then ensure corridors exist so that animals can migrate unmolested—with carnivores given trophic priority. Some argue that rewilding campaigns over-index on charismatic animals—jaguars, wolves and bears, rhinos—often tokenizing the trophic hierarchy for pathos-driven fundraising appeals. This preference of megafauna can be seen by some as extensions of empire, of erasure. In 1995, for example, Yellowstone National Park famously reintroduced wolves, celebrated by millions, but it wasn’t until recently that Native place-names were added to signage and the park service recognized the eleven-thousand-year history and presence of Crow, Shoshone, Nez Perce, and Blackfoot in the region, along with their forced removal in the 1870s. No Indigenous groups were consulted in the rewilding process.

Rewilding can too easily reinforce a binary narrative that excises humans from recovery, that says removing our presence is required to return land back to mythic purity, that humans are either to be full-time engineers or fully removed. A more just rewilding approach, reflected by Prata and his team, might insist more on M’s than C’s: Multicultural, Multispecies, and Messy. An equitable rewilding includes constant interfacing with various stakeholders, human and non-human, to decentralize the narrative itself, to square tradition with innovation and re-center the relational. Up until now, Rewilding Portugal’s main strategy has been to buy up as much land as they can to establish viable ecological “cores.” What’s required now, though, is relationship-building, working with adjacent landowners to open their land to fence-free connectivity. But this phase is more difficult, as it’s cultural, relational, and messy, a requisite learning and unlearning on both sides.

Prata and I drive to the third location, a field station and abandoned mine. Two fishing poles poke between the seats, and maps overstuff the glove compartment. Prata ashes a cigarette in his lap while navigating the roads with authority; it’s clear he’s taken this route a thousand times. We check in on two carpenters finishing the bird blind next to a surprising marshy microclimate that feels like the Deep South. Grebes move along the wetland while two herons perch on an overhanging branch. The station will be for visiting birders to track waterfowl from the comfort of a couched seating area, mini-fridge included. Across the property, a series of abandoned ponds now function as an aquaculture experiment and watering hole. Trout once flourished in the Côa, and Prata’s team is rebuilding these populations. “I saw my first wolf while fishing with my father as a kid,” says Prata. “I want to bring that possibility back for the future.”

We walk past bouquets of Iberian lavender, and while I squat to dissect a pile of fox scat with a stick, Prata finds a rare albino orchid. He’s confident the golden jackal will return; the species has been expanding rapidly. The lynx has a more promising future than the wolf here, he says. Wolf packs in the Côa have become increasingly elusive, while the Iberian lynx has been regaining its population. Less of a threat to livestock. This is exciting for Prata because the lynx was what first drew him to this work. His father worked as an investment analyst for the farming industry and, in 1990, took eight-year-old Pedro into the field. They traveled to the Malcata to visit a group researching the Iberian lynx—at that point, their population had tanked—and Prata was struck by their dedication. He knew instantly this was his future. Now, three decades later, his life centers on bringing the lynx home, just as the lynx brought him home.

“This is lynx habitat. All we need here is to attract prey. We need fucking rabbits.”

Shifting focus to rabbits invokes a flip of the script, trophic inversion. You want your lynx? Build biomass prey densities to allow them to settle. “Rabbits are keystone prey.” The success of rabbits here connects to the team’s introduction of wild ruminants—grazing indigenous horses, tauros that are related to the now-extinct aurochs, Polish bison—which all act as “umbrella facilitator” species: by grazing they constantly make new green shoots of grass, which rabbits love, while also offering rabbits defense from predators and mitigating for fire. Fire remains a constant threat to Portugal’s dry landscape. Wildfires in 2024, exacerbated by climate change, will end up burning about 350,000 acres in the country. Ranchers also like to burn these lands for grazing or monocropping. Broom loves fire, Prata tells me, fingering the yellow flowers, but it’s a pioneer species. “Burn broom every few years and the forest can never mature past first-phase succession. Burning broom to get rid of broom only increases … broom.”

Perhaps what’s more important than rabbits is a diverse flora composition—fruit-bearing sorbus, strawberry tree, common hawthorn—for these attract bugs, pollinators, seed-dispersing birds, all of which build soil. So maybe it’s soil that runs the show. But soil isn’t sexy. Shrubs aren’t sexy. Rabbits aren’t sexy. The lynx is sexy. No federal agency would commission a statue of soil to replace that lynx in Sabugal’s plaza. But if anything deserves a crown here it’s the complexity of relations itself, and how do you make a statue out of that?

Prata tells me that estimates for a full mature forest to reestablish here are 150 to 200 years. “It’s outside the human capacity to imagine.”

“How do you change that mentality?” I ask.

“Take it out of the hands of decision-making powers,” he whips. “I don’t trust the state for anything, so I have to find my way around it.” So far, it’s working. Rewilding Portugal now has a team of over twenty employees and rangers. Prata lives in an off-grid stone house in nearby Guarda, built by hand and inherited from his grandfather. His wife will give birth to a son in October, a force that drives the work he does. A common misconception about rewilding is that it attempts to look backward, to rekindle nostalgia, but it’s clear this is not Rewilding Portugal’s intent. Working with artists, farmers, shepherds, and local businesses while using unobtrusive technologies, Prata looks to a future that incorporates all vested interests—human and more-than-human.

We pull off the road at a bridge straddling the Côa, where my route continues north. “I think that a lot of what we’re doing here is finding the time and space to allow nature to heal,” he says. “We bring back some of the missing species and functions, but it’s not us managing its recovery. It’s the whole ecosystem finding its way.” I begin to thank him, but he’s already distracted by two snake eagles and a red kite thermaling high above.

Photo by Staffan Widstrand

Courtesy of Rewilding Portugal

These small gods surprised me at every turn: God as albino orchid. God as shepherd day-drinker in the middle of the path. God as pancetta offered to a wanderer at dusk. God as black-ink ear tips of a fox.

Day Four: Almeida to Cidadelhe

Eighty miles downriver, I arrive to Cinco Vilas with a brick in hand—stray dog deterrent. Drawing downstream and covered in sweat and filth, my domesticity begins to crack. Earlier at a river crossing, hours from any town or another human, I slipped and cracked my head on a rock. My phone, sole lifeline for navigation and communication, was nearly claimed by the river. In his Asian Journal, weeks before his death, Merton wrote that “True love requires contact with the truth, and the truth must be found in solitude.” After four days, I’ve begun to think he’s right, though I’ve found that all along this rewilding corridor, one feels hardly ever alone.

Field Notes:

Tan dog the size of a pot roast barks me out of town.

White roses pose in luscious protest among crumbling gardens.

Green suckers helix up a water drain next to a window where a cat naps.

Towels hang from blue clips to dry; looks like they’ve been drying for years.

Red-striped oil beetle, black armored cylinder, crosses the path with courage.

“Aigh,” says a shepherd, directing forty sheep. Long stick in his left hand.

Several sheep with red x’s spray-painted on their backs.

Sheep bells collide with church bells.

The morning pours birdsong.

Church, also.

The previous night I’d made it as far as Almeida, a walled city in the shape of a twelve-pointed star designed by French and Portuguese engineers, complete with moats and drawbridges for maximum defense and sightline. Built in the mid-seventeenth century, Almeida served as a stronghold for many generations, only falling at the hands of Napoleon in the early 1800s. With its strategic hilltop position, Almeida epitomized conquest, big kings acting like big gods in search of big power.

Cinco Vilas, on the other hand, is crumbling and empty. I enter its only coffee shop, where an old woman and her son stand behind the counter. The man, my age, smokes a cigarette as he pulls an espresso. When I tell him that I’m walking the full length of the river, he looks out onto the empty street.

“Oh,” he says. “So from the birth to the death.” After following the river for four days, I was no longer sure about this language of rivers as mortal bodies. Something feels shifty in his eyes. Yellow teeth. Body odor. White T-shirt, threadbare and pit-stained. Greying side-shave. Goatee of a forgotten mystic. Smells of chamomile waft. He tells me he’d grown up in France but that his parents moved here to rural Portugal. He left to attend university but eventually returned because this was home. He’d learned English from a British aristocrat who moved to Cinco Vilas years ago, but the man shot himself in the head and left him with cash.

“All my friends tell me I’m supposed to move to the big city,” he says, rabidly flicking his cigarette. “Big city, where you become big king. But you know what? I don’t want. I like it here. Prefer it here. My mother is here. I no want no big king. I only want to be small king.”

His words remind me of what seems to be at the very heart of rewilding. Not charismatic leaders with consolidated power, acting unilaterally, but small nobility, small gods at every scale within a landscape—like the Iberian lynx, sometimes referred to as a pequeno rei, or small king: fierce nobility, loyal to its homeland, what poet Gary Snyder once called the “ghost wilderness,” divinity living in the marbled in-between. The deeper I drew into this rewilding project, the more I began to see the threads intersecting—and also Merton’s collision of faith lines developing into a land ethic of nonhierarchical divinity. With today’s increasing torque into an algorithmic spellcasting of frictionlessness, neofascist redux, and resource hunger for an overcooked planet, rewilding is more subversive than I had first thought, an appeal to a wildness of surprise and defense of the relational, relying by design on the liberation of others to flourish.

On December 10, 1968, Thomas Merton delivered a speech on Marxism and faith to a room full of religious leaders. He identified an important dialectic: monks, like Marxists, harbored a desire for change, but while Marxists focused on the “change of substructures,” the monk was “seeking to change man’s consciousness.” He goes on to defend religion’s aim and its service to social justice—anti-war, anti-nuclear, anti-racist—while converging Christian and Buddhist praxis to suggest that the central problem is that man “does not apprehend reality as it fully and really is,” that instead we hold a deep anthropocentrism of perception where it “exists as an individual ego in the center of things.” Merton was interested in nothing short of “total inner transformation.”

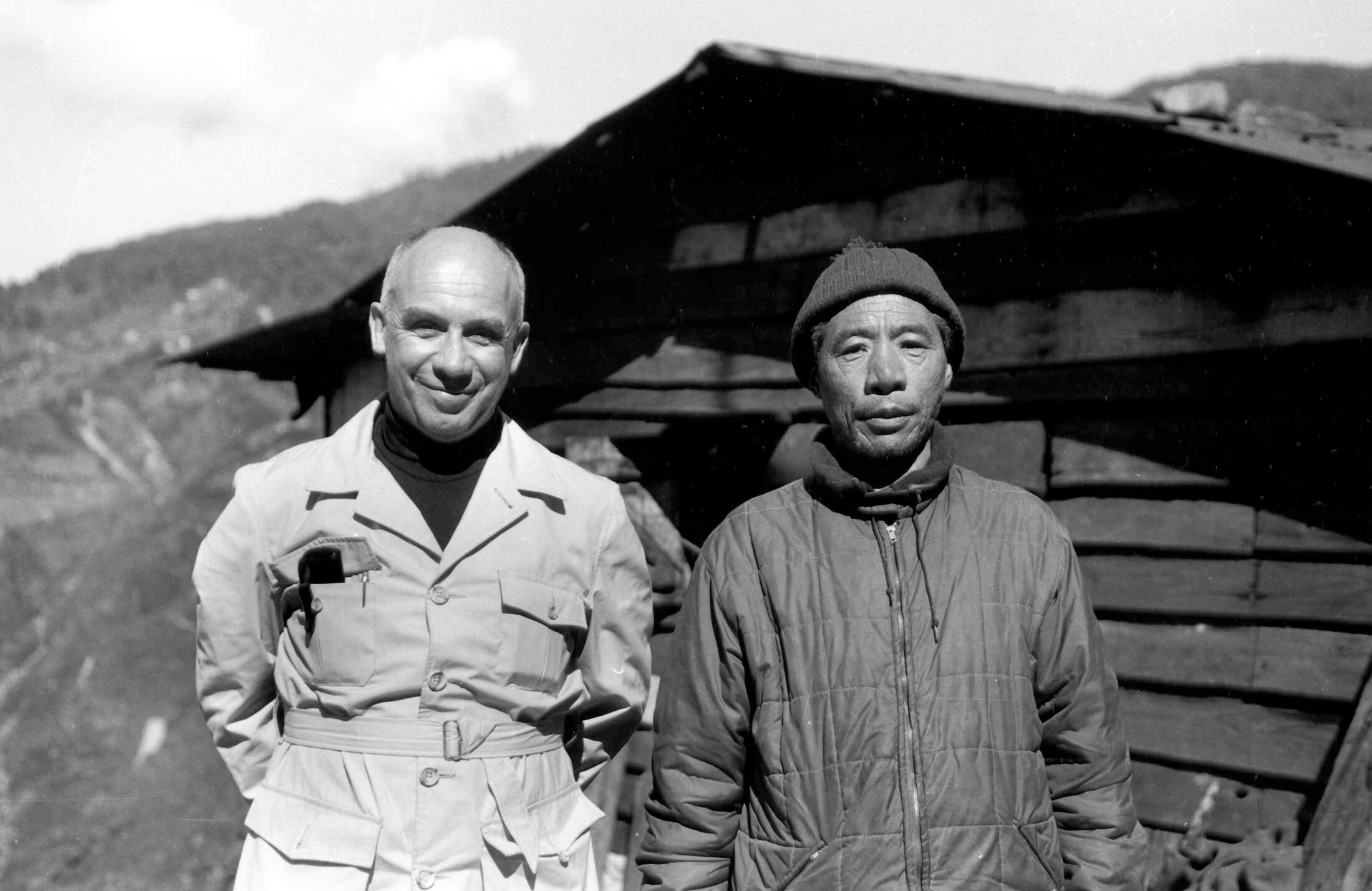

Photos from Thomas Merton’s visit to Asia in 1968. Meeting with Chatral Rinpoche in Darjeeling, India.

Photo of Mount Kangchenjunga in the Himalayas by Thomas Merton.1

Through his speech, he confronts modern alienation, that “man living under certain economic conditions is no longer in possession of the fruits of his life. His life is not his. It is lived according to conditions determined by somebody else.” Merton believed that Christianity, at its core, actually revolts against alienated life, and he insisted that we must no longer depend on structures of domination and alienation. “The time for relying on structures has disappeared.” The monk belongs fully to the world only if they are fully committed to the liberation of all beings.

After the lecture, he would return to his room and was found dead hours later. Authorities sent his body home on a military plane along with American soldiers killed in Vietnam—1968 was the bloodiest year, with nearly 17,000 killed—and he was buried at the Abbey of Gethsemani, in Kentucky.

As I finish Merton’s Journal, something unsettled but hopeful lives on in his words. Merton was convinced that the paradise we longed to attain was the living world, a hybrid Eden and Zen garden, that this ideal wasn’t some fever dream of nostalgia or some destination we must return to or engineer. It’s right here, in all its mess: “empirically real, nirvana is present and it is all there, if you but see it.” Merton’s last sentence haunts even the most secular Marxist:

“So I will disappear.”

Day Five: Cidadelhe to Foz de Côa

In these last miles to the Douro, the land rolls dry and cultivated with endless orchards of almond, grape, and olives. The Côa cuts deep and wide now and I can no longer access water. Running out, I scramble down into an overgrown culvert and traipse along a stone ledge beneath some ancient, forgotten bridge, to find a pool of brackish miracle.

Field Notes:

Dry-green hills crinkling steep. So hot, so exposed.

Griffon vulture circles high. Seven-foot wingspan.

Legs slashed, bleeding from miles of bushwhacking.

More small towns. Tile painting of Magellan’s ship above a beaded doorway.

Loquats and cherry trees line the remaining path.

Three marigolds grow through crumbled concrete.

Fire plumes near Algodres. Burning broom?

Salt encrusted hat meets sweat to sting eyes.

Douro ahead, blowing cool civility. Can hear industry roar.

Photo by Nicholas Triolo

I finally reach the Douro after walking across a train trestle at the Côa’s mouth and plunge into the confluence, where two bodies become one. Some of the world’s oldest known rock art paints nearby walls, twenty-thousand-year-old depictions of aurochs and deer, a UNESCO site dating back to the Upper Paleolithic. Perhaps I was traveling beside these ghosts all along this rivered invitation for travelers to disperse seeds, for grasses to establish, for soil and rabbits and indigenous horses to feed and to fuck, for wolves and jackals and lynx to bed down, and for trout to spawn—trophic narratives told by one relational tongue. These small gods surprised me at every turn: God as albino orchid. God as shepherd day-drinker in the middle of the path. God as pancetta offered to a wanderer at dusk. God as black-ink ear tips of a fox. God as wild boar snarl. God as a godless, post-modern skeptic trying to say “God” without apology.

Wilding knows how to defend its young to the death, how to work as a collective, how to fight against tyranny with teeth and limb. Wilding devours. Wilding sings a thousand frogs. Wilding fires through blood and semen and pierces the yellow-eyed peregrine who must feed her progeny at all costs. In the foreword to Merton’s When the Trees Say Nothing, a 2003 collection of his nature writings, theologian Thomas Berry writes: “It has been said, ‘We will not save what we do not love.’ It is also true that we will neither love nor save what we do not experience as sacred…. [O]nly our sense of the sacred will save us.”

I sit in the water, naked, resting at this collision of bodies. My body. My father’s aging body at the headwaters five days ago. The Douro. Prata’s newborn. Merton’s decaying corpse. The defragmenting lynx. Perhaps the “small king” of Cinco Vilas was right. Perhaps the end of the Côa is like a death. The death of a world, even. But probably not. As I submerge beneath the surface and hold my breath for as long as I can stand it, lungs burning, for a full minute I try and take in the entire size of this river. “All water has a perfect memory and is forever trying to get back to where it was,” writes Toni Morrison. The act of living whole might be nothing more than our irrational capacity to love deeper as we graduate to larger and larger bodies—spring to trickle to stream to river to main stem to ocean to sky to weather cartwheeling back into source, eternal flow, all of us, wild concentric gods, paddling off to some place we never left. The true current of rewilding, I begin to see, is return.

- Photographs by Thomas Merton used with permission of the Merton Legacy Trust and the Thomas Merton Center at Bellarmine University.