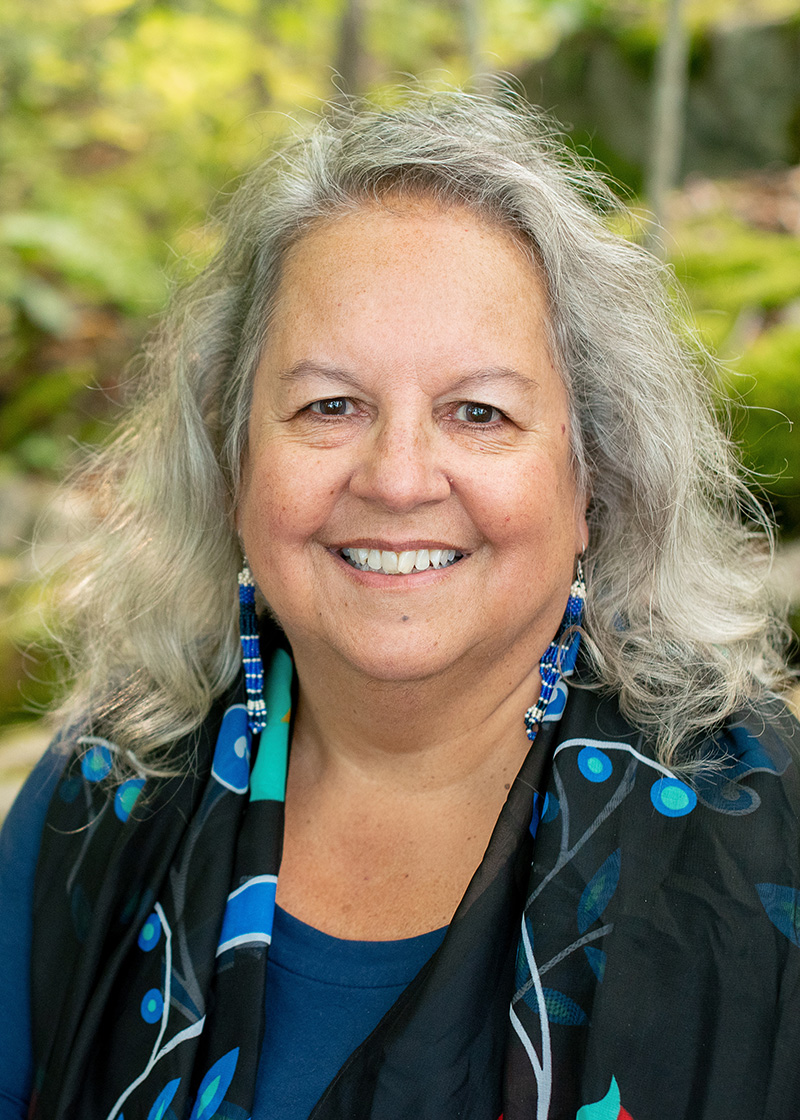

Holly Haworth is an author, journalist, and poet who writes at the intersection of ecology, history, science, spirituality, technology, and culture. Her essays and articles have appeared in The New York Times Magazine, Orion, Lapham’s Quarterly, Oxford American, The Bitter Southerner, On Being, and elsewhere. Her poems have appeared in The Southern Humanities Review and been anthologized in A Literary Field Guide to Southern Appalachia; and her book of poems, The Way the Moon, was nominated for the Weatherford Award. Her first nonfiction book, This Resounding World: A Field Guide to Listening, has received the Robert B. Silvers Foundation Grant for Works in Progress. Other recognitions include the Middlebury Fellowship in Environmental Journalism and two Pushcart Prize nominations. In addition to writing, Holly is an educator, a forager, an herbalist, and a naturalist.

How can noticing seasonal changes be a radical act in a culture fixated with endless growth? Chronicling the microseasons of the Georgia Piedmont, Holly Haworth witnesses the archetypal story of death and renewal.

REBIRTH

One day in late February it happens. I am walking under the skeletal trees and see a thin, grass-like stem protruding from the leaf litter. Along the stem are a few narrow leaves, and at the top is a white flower no larger than the iris of my eye. Each rounded petal is striped and tinged at the edges with soft pink. Five stamens sprawl from the flower’s center like the arms of the tiniest starfish; at the end of each filament is a pink anther. The spring beauty’s appearance is a miniscule but unmistakable announcement, like a flag staked in time, a precious sight to those who are looking for it. The earth is waking. The season is changing.

The spring beauty, Claytonia virginica, is one of the wildflowers called spring ephemerals, whose flowers wilt away quickly after they’ve opened. The ephemerals occupy a slender but crucial temporal niche for early pollinators. An individual spring beauty’s flower blooms for only three days, but its stamens, which produce pollen, are active for no more than twenty-four hours. We call the seasons “spring” or “summer,” pile a nuanced succession of unfoldings into one long sweep of time. But whole seasons rise and fall in a day, unnamed. I want to notice, to name them.

When I was young, I was not so attentive in my observations. I watched for the dogwood flowers, large as the palm of my hand, spring’s herald on the bare branches, white against the blue sky, when calves and foals were stumbling around on spindly legs in the fields. This was in the French Broad River Valley, in Southern Appalachia. Spring’s child, every year when the dogwoods bloomed I heard the out-of-tune warbles of my classmates singing happy birthday to you and felt glad to be born again along with the earth as it erupted in flowers and song.

As the earth whirled around the sun again and again and the line that marked my height on the closet doorframe ticked up and up, half inch by half inch, my attention to seasonal changes grew more acute and ingrained. I began to anticipate them like the steps of a dance. I listened for the just-returned indigo bunting, whose impossibly blue plumage my mother’s pointing finger trained me to see as it flashed from fencepost to grass eating newly hatched caterpillars. I watched my mother push pepper and tomato seeds into moist soil in flats in the greenhouse, marking the date of planting, and then of germination—when the green cotyledons winged above the soil like tiny birds taking flight—in a spiral-bound notebook she kept in her back pocket. She made these written records with each year’s farming season, until eventually, when the penciled line on the doorframe was four or five feet high, there was almost a whole shelf of them in the glass-door bookcase. Records of rainfall, of first fruiting, of harvests. Perhaps it is no surprise, then, that although I did not become a farmer, I would come to keep records of my own seasons.

After crouching to touch the spring beauty, which is growing where I am living now, south of the mountains, I scrawl its name onto the page of the pocket notebook I carry, along with the date: February 27, 2024. In a few days I will add the name of the Little Sweet Betsy trillium when I see its burgundy blossom open above the dark-and-pale-green mottled leaves, golden anthers trembling with expectant pollen. The next week, I will take note of a patch of trout lilies turning their yellow flowers like shy faces toward the ground, where the fleshy speckled leaves that give the plant its name have suddenly surfaced—a migration not from downstream to the headwaters through liquid currents, but from belowground to above through soil, from darkness again to light.

In the ongoing story of the seasons that I’ve been scribbling down in field notebooks this past decade or so, subtle dramas, propelled by our journey around the sun, are repeated again and again. Green turns to crimson and gold, then brown, and hides in the earth for months of quiet and stars until it reemerges. What interests me in the act of noticing and writing down seasonal changes—a practice called phenology—is refrain, which seems to enlarge my vision and grow my affection with each new cycle. In penning the names of the plants, animals, fungi, and insects, noting shifts in weather and angles of light in my journal each year, my attention is sharpened and deepened through constancy. My range has shifted these years up and down the Appalachians from Tennessee to Virginia and back, and, now, out of the mountains and into the Piedmont of Georgia—which has altered, too, my seasons. Still, there is familiarity and overlap in the story, even as the circles of my life widen outward.

In her essay “Reading Natural History in the Winter,” Gillian Osborne writes that the seasons are “inhuman, anti-narrative.” Yet our oldest and most powerful human narratives, the ones that undergird our spiritual and religious practices, are rooted in this cyclical story of death and rebirth. The seasons are at the foundation of how and why we worship. Each round, we play out the cycle again, move from doubt to faith. We can hear this in the K’iche’ Mayan creation myth called the Popol Vuh, for example, with the Jaguar Twins descending belowground into Xibalba to defeat the lords of darkness and death; in the Greek myth of Persephone—daughter of Demeter, the goddess of wheat and grain—kidnapped from a flowering meadow by Hades and kept captive in the underworld, her mother refusing to let the earth go to fruit until she is released; and in the Christian myth of Jesus, who is associated with bread and grapes and dies only to escape the dark tomb three days later. In all these stories, the seasons are embodied by human characters, pointing to how profoundly the seasonal drama is fused with our spiritual experience of the divine power of rebirth. If the seasons are inhuman it is only because they are more than human, encompassing our lives in a great whirling dance beyond our control. We are swept up in them, we surrender ourselves to their turning.

The word “season” comes from the Latin serere, “to sow,” out of which grew satio, “a time of sowing,” and then seson in Old French. Buried within the word is a promise, a mustard seed. Covered in darkness, something deep within the seed uncoils, springs forth. The force that through the green fuse drives the flower, the poet Dylan Thomas wrote. A force that makes praise songs bloom from our throats. Each year, spring is a beginning, but it is also another way to end the story of death—again and again, the earth tells us, death is not final. This story keeps going, a narrative of resurrection.

Even near the equator, where winter never comes, the stars circle around the vast bowl of night. In Hawai‘i, where I have sometimes lived, I searched for the seasons until my friend Hualālai helped me see them. When the Makali‘i constellation (called the Pleiades in Western astronomy) appears in the east at sunset, the rainy season begins, Lono. A time of rest and abundance—time for surfing and making love!, Hualālai said, laughing. In a story he told me, Makali‘i is a priest who hoards food in a net in the stars. When the constellation appears each year, the food drops out of the sky, thanks to a mouse who has—again, as in every year past—chewed through the threads. Hunger to abundance, brown to green, death to life, dry to wet, darkness to light.

GROWTH

The rise of stories with humans at the center pushed the seasons into the background, the spinning world now a stage for our perennial human business, not the drama itself. The abundance of fossil fuels and the wane of agrarian lifestyles has also surely made the earth-based and ecological foundations of many religions and spiritualities less pronounced. The darkness of mid-winter is brightly lit, the refrigerator well-stocked with fresh produce. We don’t pray over handfuls of seeds that they might germinate. If one can purchase strawberries year-round at the grocery store, one forgets that strawberries ripen in late spring in the Georgia Piedmont, and are only in season for three delicious weeks. Fragaria, the genus name given to the fruit, is from the Latin fragrans, for the sweet scent that perfumes the air when they are picked.

The fragrance lingers, carries us into summer.

Or, one part of the summer, the early part. Mark Hovane writes in Kyoto Journal that the Japanese have seventy-two microseasons, traditionally, each lasting around five days, with names like “bamboo shoots start to sprout,” “praying mantises hatch,” “distant thunder,” and “frogs start singing.” Here, it is the season of the wood thrush’s ringing songs in the morning woods, sudden and ebullient. Season of the elder’s umbels of flowers like clouds floating in tangles of green alongside the road—denser and more green by the day. Season of the days lengthening. I startle a speckled fawn from the field’s high grasses. Fawn-startled season, and the blueberries blushing on the bushes. I sip tea in the cool mornings in a wool cardigan. I gather chanterelles to cook with breakfast. Dark clouds gather into cumulus in the afternoons and lightning streaks the sky at dusk until, finally, rain pounds the roof as night falls. I sit on the porch smelling ozone and petrichor, watching the darkness flicker. With each flash the cherry tree’s black silhouette, fully leafed now, imprints on my vision.

Then there is another season, the next week. “First ripe blueberry,” I write in my notebook on June 4, “color of the sky.” The puffed white clouds above the orchard look like fluffy cobbler biscuits. They keep skiffing across the blue and don’t pour rain. Then, the next week: “Blueberry skins and seeds in my teeth.” The seasons get inside us. Fetching a bucket from the shed to fill, I take note that I’ve just begun to hear cicadas buzzing in the past week, and I relate the memory of the sound to the tart-sweet taste of blueberries, and hotter days.

High summer, the warm hum of it. The bounty and growth, when the sun is at its fullest power. On the Solstice, I invite some friends to celebrate the longest day of the year, and we fill bucket after bucket of blueberries, feast on the tomatoes and basil in my tiny but prolific garden. Summer is the season of abundance and vitality. As a child, I spent my summer days helping my mother pick beans, squash, tomatoes, peppers, eggplants, zucchini. Then, barefoot in the hot kitchen, streams of sweat rolling down the back of our necks and our foreheads, washing, chopping, stringing, breaking, blanching the vegetables to freeze and can for winter as an oscillating fan pushed a warm breeze across the room. Time to put up stores, to fill the granary. Summer is death’s opposite, an unearned grace.

Hunger to abundance, brown to green, death to life, dry to wet, darkness to light.

Henry David Thoreau wrote on June 15, 1851: “It is remarkable the rapidity with which the grass grows. The 25th of May I walked to the hills in Wayland and when I returned across lots do not remember that I had much occasion to think of the grass, or to go round any fields to avoid treading on it— But just a week afterward at Worcester it was high & waving in the fields & I was to some extent confined to the road & the same was the case here. Apparently in one month you get from fields which you can cross without hesitation—to haying time.”

Thoreau kept journals of the seasons for some thirty years. I read them regularly now as my own seasons pass, more than 170 years later. His entries fill me with deep affection, both for him—his tender, careful observations, his sensitive reflections, his curious mind—and for the seasons about which he writes. In the pages of his journal, they are the narrative, always moving forward, alive with texture and detail that conjures the entire range of feeling in the human heart. “Live in each season as it passes,” he wrote on August 23, 1853. “Breathe the air, drink the drink, taste the fruit, and resign yourself to the influences of each. Be blown on by all the winds. Open all your pores and bathe in all the tides of Nature, in all her streams and oceans, at all seasons. Grow green with spring, yellow and ripe with autumn. Drink of each season’s influence as a vial.”

I have sometimes questioned my devotion to the minutiae of the seasons—what a boring story they might make, an anti-narrative. How quaint to write the date every summer when I see the first passionflower blooming in the field. How out of proportion to the news of the day. But when I read Thoreau, I am validated in my own impulse to write about the seasons. Taking note of seasonal events is a practice that can catalyze us to experience them more fully, to drink and taste them. It is a way to sear them more deeply into our skin, blaze them into our eyes and hearts. My journals extend off the page, on my many walks, my hands full of fruit and forage, my pores open; I am blown on by all the winds, resigned to the influences. The swells of subtle emotion that the seasons conjure in us as they pass again each time contain within them all the spirals of our seasons past, the hopes of seasons to come. I suppose this is also to say, if it is not clear by now, that phenology is to me not just record-keeping but a kind of scripture. In this repetition and refrain, a single season gathers our memories and dreams as we add new layers of meaning to our lives—as we orbit the very meaning of being alive.

In the summer of my twenty-third year on the earth, twenty years ago now—perhaps when blueberries were ripe and when passionflower was blooming, though this was before I noted such things—I learned, for the first time, about climate change. All the seasons of my life flashed before me as it sunk in that no season would ever be the same on a warming planet. Aside from catastrophic weather events, the primary observable effect of climate change is the disruption of the seasons: flowers blooming too early, before their pollinators have emerged, summers growing hotter, winters colder, freakish late frosts.

This is why I have been turning my attention toward the seasons so devotedly these past many years, keeping my field notebooks: to draw myself closer to the earth’s cycles whose disruption is, in fact, the most important story of our time; to keep myself centered; to not turn away from the story of these ancient cycles, even as they are unraveling; to insist upon the circles when the narrative of our fossil fuel–driven global economy is a straight line of upward growth, like an endless summer.

DECAY

The leaves must always fall.

Death in an ecosystem is metabolized into compost. Fallen leaves feed vital nutrients back into the soil. As leaves decay, they leach nitrogen, potassium, and phosphorus. A whole teeming world of bacteria, fungi, and invertebrates flowers here in the decomposing leaves. They are a habitat for lightning bug larvae that will nestle there until they effervesce one dimming dusk next summer—I think of this future bioluminescence hidden in the lightless rot. Through the leaf litter snake thousands of miles of mycelial threads—future chanterelles and honey mushrooms for my plate.

Endless growth would deprive new life. The cycle must be fed. This is the problem with the straight line that rises ever upward. It is in opposition to the most fundamental story at the heart of the sun-circling earth, that to everything there is a season. When summer burgeons as if to burst, it dizzies and spins into fall—slows, retreats, rests. All things are transient, impermanent, the Buddhists teach. “It is agreeable to stand in a new relation to the sun,” as Thoreau put it in his journal on September 18, 1852. The change of the seasons renews our vision, allows us to compost and digest our zenith dreams, sleep on them come winter. This time of year is for drawing back, harvesting the fruits of our labors, gathering in celebration, taking stock. Humbling ourselves to the cycle, the coming darkness.

Climate scientists are using Thoreau’s journals in phenological research, comparing his dates to current phenomena to study shifts in the New England seasons. Their research shows that some tree species are dropping their leaves earlier because of increased drought and heat through the summer. Even as summer stretches out longer and hotter, then, fall is beginning earlier, a confusion of the seasons, of our senses. Leaves falling too early can mean less food for caterpillars, thus fewer caterpillars for birds before they embark on their long winter migrations; fewer caterpillars in the fall means fewer going into chrysalis, fewer emerging in spring when birds return from their wintering grounds. How will cycle after cycle of seasonal disruption—what climate science terms “season creep”—erode our ecosystems? Will there come a day when we cannot tell what season it is, when there are no seasons to speak of anymore, when one long season of chaos descends?

I visit a field of goldenrod down the road from my house, its genus name Solidago referring to the sun. The smell of goldenrod is the smell of the sweet golden days, this brilliant season between summer and fall, another with no name. I stand in a new relation to the sun. It electrifies my every cell. The color of goldenrod flowers is the feeling in my skin. In Appalachian folk medicine, goldenrod is brewed as a tea to rid its drinker of the blues. In the field, grasshoppers buzzing around me, I cut thick bouquets of the flowers to hang and dry for winter. Every year at this time, I wish that time would stop, that this season would go on forever. But I know that it can’t be so, that the earth must keep turning, which makes these days all the sweeter. I write these days down so I can remember.

DEATH

I wonder, will climate scientists in years to come study my journals? Will they be used to document the shifts that are happening? For to write anything down is always to write for the future, to imagine a reader in some future season. Winter is a time for introspection. I reflect on the seasons that have passed and wonder what might come to fruition.

Here in the Georgia Piedmont, winter is mild, but the days are quiet, the trees bare, the fields brown. I watch a murder of crows gather in the top of a loblolly pine, listen to them caw at one another as they flap their heavy black wings and settle on the branches. In the mornings I step out to watch the sun blaze above the horizon and light the orchard. Sun!—that great bright burning mystery around which we circle. It rises now at the edge of the woods, having walked the horizon southward from where the well house stands since the Summer Solstice.

Growing up, on the shelf of the glass-door bookcase next to my mother’s farming records was a paperback copy of Aldo Leopold’s A Sand County Almanac. Writing from his family’s sandhill farm in Wisconsin in the 1940s, Leopold recounted the quiet dramas and marvels of the seasons. My mother read the entries aloud to me, and it was in these stories, too, I realize now, where I learned that time moved in circles. For Leopold, the seasons were told by tracks in the snow, skeins of geese embroidering the sky, the river’s spring floods, spawning trout plying the currents.

Leopold wrote his almanac month by month. The root of the English word month is “moon,” that heavenly body that orbits our earth, by which all the Native people of this continent, and the world over, long identified the seasons. Moon!—that great glowing mystery that circles us. Before settlers arrived with “January” and “February,” with “summer” and “winter,” the numerous tribes of Turtle Island, speaking some five hundred languages or more, named each of the year’s moons based on phenomena in their local ecologies—moon when the chokecherries are ripe, for example, moon in which wild rice is laid up to dry, moon when animals prepare for their dens, moon of rutting reindeer, moon when the dog is cold. Silver salmon moon. And so there were once thousands of singular bioregional seasons unfolding across the continent’s diverse terrain each year.

Abenaki storyteller Joseph Bruchac writes that for most Native nations on the continent the time for telling stories was between first frost and last frost. I spend the winter reading books. In a history of Egyptian gods and goddesses, I learn about Thoth, the god both of scribes and of the moon, and it occurs to me, then, that writers have always been the timekeepers, the ones who marked the moon’s phases and cycles in literate cultures, who kept the seasonal and agricultural records. These were also ways of looking ahead to predict the seasons based on historical patterns—what was traditionally called an almanac.

I spend the winter reading Leopold’s almanac, reading Thoreau, and it strikes me that although neither of them could have known our seasons would become disrupted, both were consciously working to keep the story of the cyclical nature of time and the seasons alive as the culture around them became enamored with time as a straight line. In Leopold’s foreword, I read: “Now we face the question whether a still higher ‘standard of living’ is worth its cost in things natural, wild, and free.… We of the minority see a law of diminishing returns in progress.” And in Thoreau’s Walden, which was also something of an almanac, almost a full century earlier: “My greatest skill has been to want but little,—so little capital it required.… The laborer’s day ends with the going down of the sun, and he is then free to devote himself to his chosen pursuit, independent of his labor; but his employer, who speculates from month to month, has no respite from one end of the year to the other.”

No respite from one end of the year to the other—this is a life without seasons, a life lived along a straight line, the life of progress, of endless economic growth. For Leopold and Thoreau, writing the cycles as narrative was a way of preserving them. Before they could understand that the burning of fossil fuels would literally rupture those cycles, they were concerned that we were losing the story that time moves in a circle. Now we know that stories themselves can break time—that the straight-line story of perpetual growth is the very thing that has disrupted our seasonal cycles. That story, which runs especially rampant in the dark days of winter—the Christmas season, we call it, time of the most intense and wasteful capitalist consumption—tells us that we must keep accumulating things to get ahead, that we need more and more things to be happy, that things are the gifts we all want.

Immersing ourselves in the seasons, writing them down, is a way of telling an old circling story we need to hear—that everything will circle back to us, that there are no closed systems, no “externalities,” as economists call toxins and emissions. This is the primary story of ecology, a story that insists upon the circles. Now we know that carbon moves in a cycle through the ecosystem, from earth to atmosphere, that all our waste must go somewhere. The story of death and rebirth. It is our oldest, truest narrative.

Spending time noticing the gifts of the seasons is one way of participating less in those activities that are fracturing them. And it is how I have come to understand we can want little but have so much. At the end of December, the leaves on the blueberry bushes turn crimson. They leap up like flames, like so many fires to keep my eyes warm and alive, to keep my feet flickering along the deer paths that thread this small patch of land. I follow their hoof prints on the creek bank, pressed into the cold mud. Song sparrows flit through brush and foxtail grass. The long nights of darkness make the stars dance. I fill my notebooks.

“The Force That Through the Green Fuse Drives the Flower” by Dylan Thomas, from The Poems of Dylan Thomas, copyright ©1939 by New Directions Publishing Corp. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp.