Time: A Conversation at London’s Architectural Association

Emmanuel Vaughan-Lee is an author, Emmy- and Peabody Award–nominated filmmaker, and a Sufi teacher. He has directed more than twenty documentary films, including Taste of the Land, The Last Ice Age, Aloha Āina, The Nightingale’s Song, Earthrise, Sanctuaries of Silence, and Elemental, among others. His films have been screened at New York Film Festival, Tribeca Film Festival, SXSW, and Hot Docs, exhibited at the Smithsonian Museum and London’s Barbican, and featured on PBS POV, National Geographic, The New Yorker, and The New York Times Op-Docs. His new book, Remembering Earth: A Spiritual Ecology, is forthcoming from Shambhala in summer 2026. He is the founder, podcast host, and executive editor of Emergence Magazine.

Marko Milovanovic is an architect, artist, and journalist. He is the founder of the knowledge and space production practice Mylomark and the educational platform Free School Of, which celebrates conversation as a fundamental form of knowledge. He has worked on a number of award-winning healthcare, commercial, and educational buildings and written extensively on politics, culture, and urban regeneration for major Serbian newspapers. Marko currently teaches at the Architectural Association, the Royal College of Art, and Oxford Brookes University.

Held in May at the Architectural Association in London, this conversation between Emergence executive editor Emmanuel Vaughan-Lee and architect, artist, and journalist Marko Milovanovic delves into Time, our fifth annual print edition. Ranging from the kinds of time that can bring us back into relationship with the living world to the mystical Sufi poet Rumi, this talk explores the vision behind Emergence to help reweave the worlds of ecology, culture, and spirituality, and once again understand the Earth is alive, animate, and sacred.

Transcript

Marko MilovanovicGood evening everyone. So I just told Emmanuel that I don’t really know where to begin, or how to begin, but also that I actually have many different ways to begin. So maybe a good way to start is for me to say why I think Emmanuel should be here, and Emergence, here at the Architectural Association. And I think a good reason is very much that the Architectural Association is a very ephemeral place. It allows for a study of architecture in most ephemeral ways—immaterial, of course also material. But what I myself do with my students, we observe a lot, we go to remote landscapes and we just look at things and often use a camera to capture those observations and then through the process of editing and thinking and conversing about it, we produce, I guess, some form of knowledge which we then slowly over a painful year—for some—turn into architecture.

And so I think maybe this way of talking about architecture can already begin to resonate with Emergence and with the way that Emmanuel approaches editing of a magazine, but also just generally the work that you do on many different levels from, I’d say, philosophy to filmmaking to things that are quite technical to curating, which is really an act of curation, I would say. So I think those are all different reasons for you to be here. And maybe I could ask you if you agree.

Emmanuel Vaughan-LeeYeah, I mean, I think what I find so interesting about the way that you work, Marko, is it’s—as you said—it starts from an ephemeral place, and then it gives space to explore what can emerge there, without having really defined boundaries of what architecture is. And so I would maybe make a parallel, that I approach Emergence as not being restricted, I would say, by a conventional definition of what a magazine should be. And starting from an ephemeral place based on a loose idea or a value or a feeling. And then trying to find a way to bring that into being through experimentation and creativity and collaboration—which is, I think, what you often do with your students and what happens here at the AA. And truly trying to expand what we think about as a beginning and an end for a story to be told. And what is the entry point? What is the end result that you’re trying to offer somebody, which I think you could say is also what can happen when you go into a building. You’re creating a space for people to experience something, transcend limitations, and emerge from that space hopefully changed in some way for the better.

MMAnd so I quite enjoyed that you’re talking about Emergence as something that you do and how you approach it. But obviously you started with Volume 1, which means that you started somewhere, which means that it was an idea or there was an urgency for a certain kind of thinking. So maybe I’d like to take you back to just the beginning and maybe you could tell us a little bit about why this was necessary, but also how did we get to Volume 5?

EVWhen we first started, we were thinking primarily as an online publication, not as a print publication. And the print concept came a little bit later. As we started publishing material online, we started thinking, can we present this material that’s honestly quite ephemeral online in a physical form that would be like a testament to the work and the ideas that are explored that would be something that could last as a physical object. And so after a year of publishing online, we went back and looked at the stories that we had released and started to think about how those stories could be redesigned and offered in a print form, in a curated experience. Because it’s very different to have something in print versus online. Online experiences, like you go to a link, you go to an article, you go to … whatever it might be, and you experience it usually as a stand-alone story. But when you’re flipping through the pages of a book or a magazine, it is an experience which takes you on more of a journey. And so it was an opportunity for us to, in some ways, reexamine the narrative of what was emerging organically as a publication.

So Volume 1 didn’t have a theme. It was literally just “Volume 1.” And it was a collection of, I think, thirty different pieces. And then Volume 2 followed that trajectory. And it was another collection of what we had published online the following year. And then the pandemic hit. And just before the pandemic hit, we had been publishing on the theme of apocalypse. And then the pandemic hit. And we started thinking about that and where should we go next as a publication in response to the moment, and where we were being taken collectively and also individually, and as a publication. And we came up with this concept of “living with the unknown,” which is the only way we could describe the space that we were in at the time. And everything could shift in a moment’s notice and there was really no guarantee about what anything would be like in a week, a month, a year. And that became a space to create from.

And we created a print edition from the ground up for the first time under that theme, working with different artists and writers and poets. And then this kind of series of themes emerged from there. From Living with the Unknown we went into Shifting Landscapes, which is kind of a natural extension of that space: in the space of the unknown, things are shifting, landscapes on all sorts of levels, physical, metaphysical, inner and outer. And from there, we started thinking about, if the world is unraveling in the way that it is in all these different ways, we have to reexamine some of the most foundational ways that we relate to the world.

And for me, what is more foundational than time? Time is something that is so simple and common, yet anything but. And it’s also become something that has been completely ripped apart and controlled for the sake of a mechanistic worldview bent on destroying the planet. And it allowed us to work with this large frame, which we really like to work with: living with the unknown, shifting landscapes. You could take that in any direction. Same thing with time.

MMAnd there must have been, you know, I know in previous issues, you actually identify ecology, culture, and spirituality as maybe some core threads. And what about those core threads that run through all of the issues? How do they emerge? How do they connect?

EVThat’s our tagline. And so, to me, everything that we try and publish and work with is a manifestation of those worlds coming together. And part of the origin behind Emergence as a publication was the need to try to create a space that identified the problems that we’re dealing with as a disconnection of ecology, culture, and spirituality. Spirit has been separated from the environment, the natural world, the living world. Our culture has become disconnected from the living world. Our culture has become disconnected from spirit. And the need to reconnect those worlds is paramount if we’re gonna respond to the crisis that we’re facing. We can’t just look at it as an ecological crisis or a cultural crisis or a social crisis—or a spiritual crisis. They have to be looked at together. And story has this power, this alchemical power, of weaving worlds together. So that became kind of the editorial frame, if you will, for how we approach what we do.

MMSo it sounds as if you see it more as a kind of forum, a discussion, discursive place, rather than necessarily you having a very specific, let’s call it “agenda,” in terms of the message that one should take.

EVYeah, I would agree with you. I’m weary of agendas. I think agendas also limit the scope of how you can express—and you’re unable to be responding to the moment. And “emergence,” the title of our magazine, is to create a space where something can come into being, something can come alive. And if you create a certain set of conditions, then something can come into being. And it’s not you who’s necessarily doing it. It’s many voices. A magazine is … how many voices here? Many, many voices. And there are the voices within each of one of those stories, and if those are held in a certain way, then something can emerge from the interplay that can happen through those voices. So I’m really interested in creating those spaces rather than thinking like, here’s an agenda and a message. And early on we started thinking about our publication almost as if it was like a salon, a space that used to exist only in the physical, where people would come together and talk about ideas. But that can happen in a magazine, in a physical form, it can happen online, it can happen in a conversation, it can happen in various ways where there’s experimentation and things can build off of each other. Artists coming together, creators coming together, all drawn by a central desire to want to challenge the status quo and not be afraid to use the word “spirit” and “beauty,” or even “God,” “love”—all of those kinds of things in response to what is unfolding. And to not follow any prescribed norms of what a story should be like, you know, just like we shouldn’t be stuck in what a magazine should be like.

MMMaybe, I mean, I’d love to find a better word than “agenda” to ask about your spiritual teaching. What would be a better word?

EVFumbling, fumbling, fumbling.

MMTo something that has a kind of vision or a value system, or a vision of a value system, let’s say. And we start this issue with Rumi, with a beautiful quote, which says, “Step out of the circle of time and into the circle of love.” And, of course, maybe I should actually ask you to talk about Rumi beyond this quote, because I think we often talk about Rumi—

EVYou do?

MMWe. No.

EVI want to be in your conversations.

MMWell we should talk—

EVWe should definitely always talk more about Rumi.

MMBut I do think when we react to Rumi, we react to these quotes, but I think there’s a lot more to Rumi than the quotes that we have all seen in various places. And of course, Rumi being a Sufist, and this issue starting with that, I think there is maybe some level of—some underlying value system that also connects to you and your, I guess, spiritual work. So I’d just like to understand how these things connect and how one informs the other.

EVMy own spiritual practice, my own Sufi practice, definitely informs all of my work. And we used to hide the Sufi hidden breadcrumb in the back, you’d have a quote, like in the first issue there was a quote of Rumi, like, hidden there. And in the next issue it was a little less hidden. There was one of Rabia, and there was one of Attar. And for this issue, we didn’t want to hide it. Not because I’m trying to say, like, I’m a Sufi and this is work of Sufism. it isn’t. But because the quote that opens the book, “Step out of the circle of time and into the circle of love,” to me is really what this issue is trying to offer. And what I think Rumi does so powerfully, to anyone—whether they’re a mystic or not, a Sufi or not—is, he offers an invitation to step into a larger reality. And that larger reality is not consciousness or conceptual: it’s longing for something larger than oneself, it’s a space of love. And that has always been at the core of what motivates me, is longing.

And this issue is trying to evoke that. Not to say only in a personal sense, like to evoke that love for one’s own desire to go home, whatever “home” might be to each person. But going back to the premise of what Emergence is about, this crisis that we’re in, that we need to weave these worlds back together—to me, a central ingredient in weaving those worlds back together is love. You know, as my dear friend Sam Lee, sitting right there, said to me not long ago: How are we going to protect what we don’t love? What we’re not in love with? And I feel one of the deepest crises is that we’ve fallen out of love with the Earth. And we need to fall back in love with the Earth. We don’t just need to challenge our governments and change our policies and keep the oil in the ground, but we need to actually fall in love with the Earth as individuals, and if we can, as societies.

And this magazine, this issue, is a series of invitations to step into a space of love, defined in many different ways, and that Time is much larger than our humancentric notion of time. And perhaps love is a gateway for us to go beyond our limited understanding of time, if we allow our hearts to open ourselves to spaces rather than purely our minds. And that’s what I think Rumi does so well.

MMBut is he also a revolutionary? Is he also reacting to a certain political landscape?

EVYeah, he was considered revolutionary in some ways, in Turkey in the thirteenth century. Yeah, Sufis were often considered revolutionaries, because they weren’t interested in any sort of literal interpretation of religion. They were interested in a direct experience of God. And that’s always threatening to people, because it cuts out the middleman. And you can’t control if there’s no middleman. So he was revolutionary, and his poetry is revolutionary. He’s inspired countless poets and writers and artists whose work has been revolutionary.

MMAnd then revolution then—I just kind of want to somehow go into this political domain, which actually this issue does also address in a few instances in an interesting way. I mean, “An Essay of (K)nots and Footnotes,” by—I don’t want to mispronounce the author’s name.

EVBy Layli Long Soldier.

MMYes, yes. Maybe we could talk about that essay for a moment, because I feel there is a real relevance to it in the contemporary world. It talks about land, in some way, land dispossession and relationship to land and a kind of oppressive nature of the US government towards the Native American population from a very personal point of view. And yes, there is no reference to the kind of major crises in the world right now, but I think very much this is a universal story. So maybe I’d like to talk about the universality of that beautiful essay.

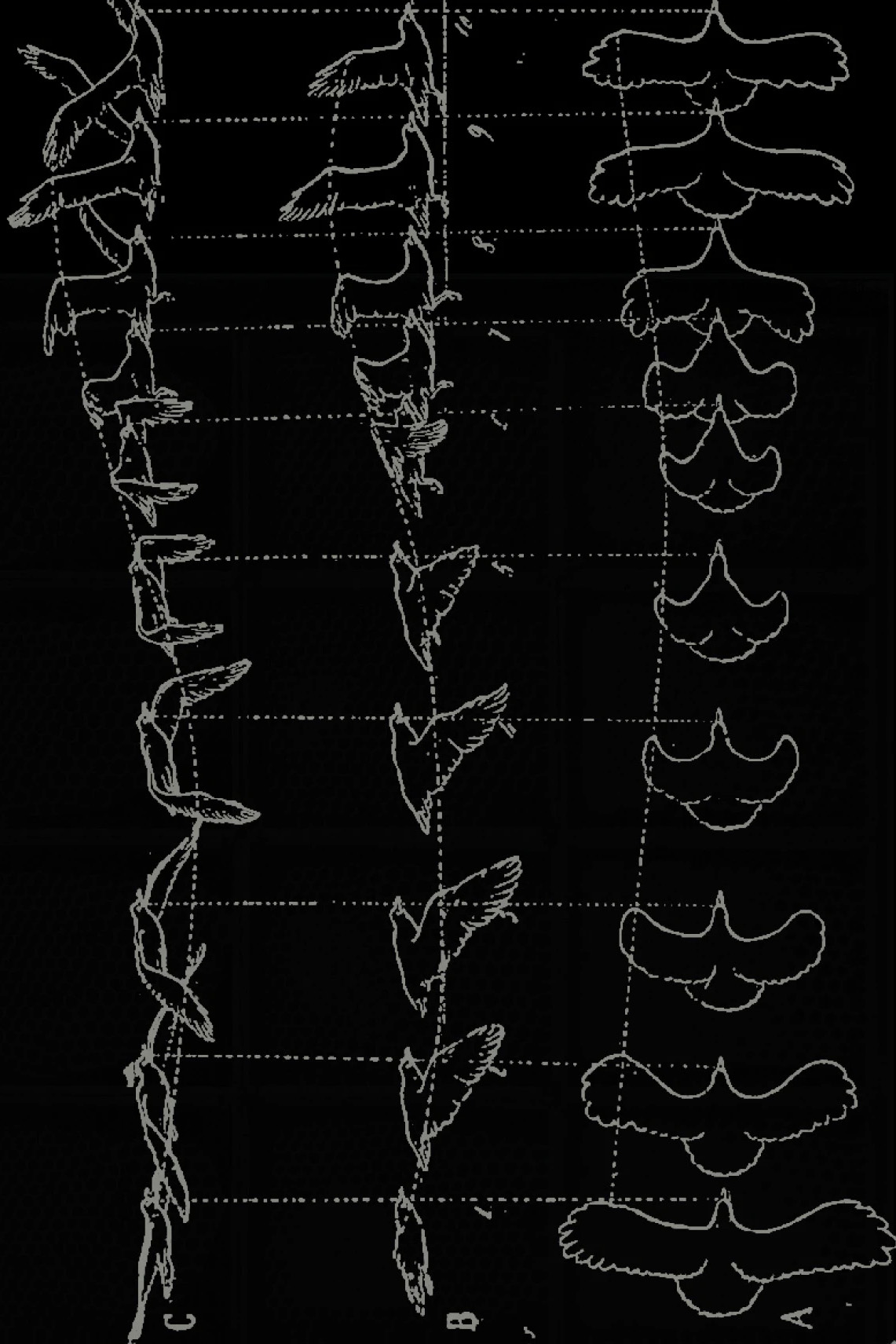

EVYeah, it’s a very interesting piece. Layli Long Soldier is a remarkable poet and essayist and writer, Native American. And she responded to our prompt about ancestral time, actually, because the original idea behind this issue was to explore time from four vantage points. The first one was time as a tool of control and domination and colonization. The second one is how we have actually sped up the nature of time: geological time is now moving at the speed of human time. And the third area was really slowing down and embracing other kinds of time, nonhuman time. And the fourth section was looking at ancestral time, mystical time, and the future. And so Layli looked at this prompt and came back and said, “If I’m going to talk about ancestral time and I’m going to talk about the future, I have to talk about the past.” And she told a story that was very personal to her about her people and about dispossession of land. And a story that’s very present in America for Native Americans. And so time, for her, had to be held within the personal experience that she holds, her tribe’s experience, and the historical reality that, for many people whose land has been dispossessed—they are living in the future, but they’re also living in the past. And until we recognize the realities of what has happened and take ownership of it and offer restitution, in some form, even if that is just acknowledgment—that’s not a “just,” that’s a big thing when it’s never been done—then the future cannot unfold in the same way that it might.

And that’s a very— her essay is about a lot more than that. And it’s very interesting because it’s told through two stories: on the top in black is one essay and on the bottom in red are footnotes. And the footnotes are longer than the essay. And it’s a narrative that unfolds. So it’s a very interesting way that she created this experience of the past and time and ancestry. And it is deeply political. Her story is deeply political, because the reality of dispossession in America butts up against the political history of America in the past and the political moment where we are now.

MMAnd how is this story— Do you think this story is also universal?

EVI think there’s been land dispossession everywhere. So yes, I do think there’s universal themes present in Layli’s piece, but I would also say that the experience that she describes is also very specific to North America. And so I think it’d be dangerous to simplify and say it’s universal. There’s different ways that land has been dispossessed, but it is a universal story of land being taken from one people and never given back.

MMI guess an interesting quality of the magazine is— There is a certain timeless quality to this publication. I often think of magazines as a section in time. You know, if we pick up any magazine from about three years ago, we will get a really interesting sense of where we were culturally in that moment in time. So I feel a magazine as a format is in some way a section in time. But then there is a certain timeless quality to Emergence. And I was looking through these earlier issues today, and I was really getting a strong sense that so many of these stories still resonate and could have been written last week. And so I just want to maybe ask you whether you think about this. And in that sense, I guess, how much do you think about the timelessness of the stories that you put into the magazine?

EVIt’s very intentional. One of the things we first discussed at the outset of creating the publication was to not publish material that would no longer be as relevant in one or two or three years. We wanted all the stories that we published to be evergreen and that they should be valuable in ten years, in twenty years. While they may have shifted in their relevance in some way—because the cultural landscape is shifted—they would still be a valuable contribution.

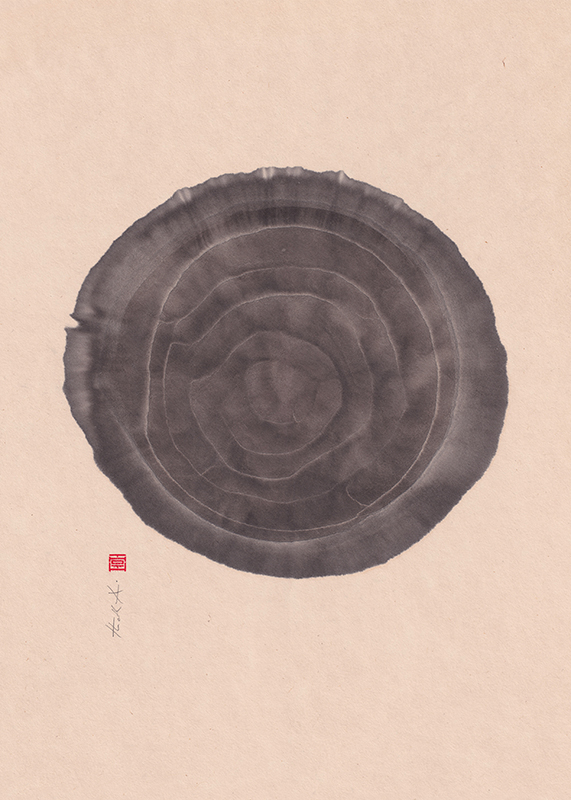

We don’t really do much reportage, for instance—a little bit. But even when we do that, we try to make sure it doesn’t get locked into just telling a story that’s valuable and relevant for a certain moment. And that’s why we mostly work with the essay form. And when we work with photography, it’s not trying to capture a specific moment, but rather to evoke a feeling and take you into a space. And so all the pieces here—they are reflecting what’s happening right now, but they are not caught in that moment. They’re trying to take you from the time bound to the timeless. And that’s something we try and do in all of our work.

MMI wonder, how do you do that? Is it in the narrative form? Is it in the physicality of the object?

EVYeah, I think it’s in the narrative form. I think it’s part of what we discuss with writers and artists. It’s a little easier now because people know that Emergence isn’t a place that publishes short-form content that’s newsworthy. At the beginning when we were in discussions with artists, we’d have to talk to them about, we actually want to write, you know, work with something that’s going to be relevant, you know, in five or ten years. But a lot of writers love that, because, you know, they don’t want what they write to be only relevant for a snapshot. It’s one thing if you’re writing for a newspaper. And although this is a magazine, again, from the beginning we were like, we want to make sure we don’t get defined purely by existing ideas of what a magazine is.

And we work with long-form content. So when you write longer content, you have to work with narrative. You know, if you write a thousand words, you can do anything. You write ten thousand words, It’s a little different. You have to create a narrative, and what is that narrative? And it has to be a good story, and a good story has the power to transcend only being valuable in the moment and be evergreen.

But to me it’s a lot more interesting to create work that’s relevant on a shelf in ten, twenty, thirty years, not just as a snapshot of the cultural moment in time, but a collection of work that builds upon each other and influences other work to create an experience of this emergent field of, I call it “spiritual ecology”—where we’re bringing back together an understanding that the world of matter is sacred and alive and animate and should be revered. And story has the power to do that. And we try to build on that and not have constraints about trying to cover an issue and say, “This is what happened at COP this year, and this is what failed at COP this year. And this is what we’re hoping will happen next year.” Rather we’d wanna look at the broad values and ideas that might be relevant in those questions and then find a way to express them.

MMI mean, that’s interesting, because the world is changing, right? The world has changed since your issue one. In some way, there is an element of relevance that’s important.

EVYeah. Trump was president when we started, and it looks like he’s gonna be president again next year. So I think we’re stuck in a horrible time loop.

MMAnd I think, I find it really interesting that culture sits between ecology and spirituality. And I think this is one of the things that I maybe asked you when I interviewed you last time. I’d like to explore this notion of culture in relation to ecology and spirituality. And whether this is— To me, like a magazine is a cultural form in some way. So I wonder how you see that relationship and what really— I think “ecology” in some way and “spirituality” are terms that I can understand, but I think “culture” is a very multifaceted term, and I’d like to understand how you understand it.

EVYeah, me too. You know, it is a multifaceted— so is “ecology,” so is “spirituality.” I would challenge the notion that the other two are like, “Oh, I’ve got that.” I think the living world has more mystery in it than we can ever understand. Spiritual traditions are just trying to catch up to that. And culture is just lagging behind. That’s my take on it. I feel like culture has yet to catch up to the majesty and mystery of the living world, and it has become devoid of spirit and beauty, at least en masse. And so I feel like it’s sandwiched in the middle because it needs extra love. It needs a love of the Earth, it needs a love of spirit. We’ve got to infuse culture with those two things, and then maybe we got a chance, I don’t know.

MMMm hmm. No, I think that’s interesting. So I guess we spoke about those lines that run through all of the issues, and partially those three terms captured those threads. Maybe if we again talk about the latest Time issue and this journey that you earlier mentioned from the, in a way, cosmic geological time, to a time that we experience with our bodies, to really, in a way, towards the end of the issue, it all sort of dissolves in a most beautiful way, and we talk about love. So maybe that final piece, whether it’s the final piece, that really centers love at the core of this understanding of time. I think that’s something that I’d really like to understand, or I’d like you to share with us—that understanding of love in relation to time.

EVWell, it’s a piece by my father, Llewellyn Vaughan-Lee. It’s my favorite piece in the— I guess I’m just, you know, love my dad’s work. But to me it’s the most important piece in this magazine, because it’s a culmination of where the journey of the other stories have arrived to. And it’s a personal story of his, and it’s also a story about the state of the world. And the opening quote on the page is that “It is the axis of love that is present in all things.” And what he explores in the piece is that the essence of time is love. And once we strip away our ideas of what time is, there is something that is universal in every single form of time. The time that is in our bodies, the time that is in this room at this moment, the time that is in the tree outside, the time that is unfolding in a cycle of a day, a cycle of a season, a cycle of a year. There are these endless cycles, each embodying different forms of time. And what is the universal energy that is present in all of that? He describes it as love. I would describe it as love too. But that’s just two Sufis talking. But, you know, the opening quote—”Step out of the circle of time and step into the circle of love”—it’s an invitation.

And so this piece is culminating in all these expressions of time, of the limitations of our own experience. of the world because of the constraints that have been put on us by controlling us to be just mechanized extensions of a clock, to the reality that what used to unfold in a thousand years unfolds in ten years. That’s pretty amazing when you think about that statement. All these different ways that time has shifted. But also the ways that we can shift in the midst of that limited and crazy change that we’re experiencing to reorient ourselves to what is most essential.

And so, that’s what he’s inviting people into in this piece—is to step into something that is there. It’s present in all things. Just as Rumi said: you step out of a limited idea of your reality or the self or the world, and you turn your gaze elsewhere, and there is love. And then that love can blossom inside of you, but it can also blossom in relationship to the world around you. Going back to what I was saying, you need to fall back in love with the world. How is that going to happen? It’s not going to happen by somebody telling you to do it. It’s going to come from an experience. You know, it’s like Sam takes people into the woods this time of year to hear the nightingale sing. And that experience opens their hearts. It opened my heart when I went there. And then there’s this love that is awoken, and that love doesn’t necessarily just disappear when you wake up the next morning. It’s there inside of you. And then things change, and the way you perceive the living world, the way you perceive community, the way you perceive all these different realities around us has shifted. And this issue of Time is just that: it’s an invitation. Whether you’re talking about time—it’s just a metaphor for the living world and how it functions. And within all these various forms that we have turned away from—only to want to look at ourselves in the mirror—is this essential ingredient, which is as old as we are. And much older, if you want to look at it.

MMAnd can you, I think it’s very fitting that that’s the last piece, because in some way it offers another way of reading all of the preceding pieces. So it shifts perspectives on all these different ways of engaging with time, which have been laid out as we approach this final piece. And I guess maybe I just invite you to maybe reflect on any particular essay or image that’s anywhere preceding this last piece through the kind of prism of this final piece?

EVI mean, the reason that we didn’t open with that piece is because— One, we wanted to mirror in some ways the experience that we’re all having, which is one of being confined and limited in our understanding of time by the societal weight that is always down upon us. And starting from there and being uncomfortable and looking at the realities. There’s a piece by Roger Reeves that really talks about the impact of a dominant white culture on Black experience of time. And then you’ve got Layli’s piece really looking at the realities of how time has impacted her people’s relationship to land, right? So you’re having to face the realities of where we are and be uncomfortable, but in the process, maybe slightly opened. And as you go deeper and deeper and deeper, ideally, you are more open to actually go, “Yeah, I can get behind this whole love thing.” Maybe if you start with the love, you might be less inclined, or you might— who knows? You can read it back to front. That’s also why it says ”Time” on the front, “Time” on the back. And there’s no page numbers.

So who knows? Maybe you’ll start with the last essay and go there. But it isn’t also necessarily designed to be read from left to right. I’m always curious how people engage with our physical objects that we create, and people are drawn to start in the middle, start at the beginning, start at the end. You never know, and that’s the wonderful thing. You can offer a guided experience saying, “Okay, we’ll be conventional and start left to right,” and go for control into this more expansive way of seeing things. But some people might go right to the very back and read it. But to me, each one of these pieces is about love in its own way. Some are more directly expressing it and some are more hidden in their expression of this. But they’re all talking about the need to return to something essential and how that form of essential nature of time, love—it takes many forms. That’s the beauty. It takes so many forms, and we’ve homogenized it and said—we’ve homogenized everything, we’ve homogenized time, we’ve homogenized love. Let’s limit everything. And we’re trying to expand and open us up to questions. There’s more questions that come out of this volume, I hope, than any answers. There’s no prescribed, “Well, okay, let’s fix the world by embracing these kinds of time.” No, there’s none of that.

MMAnd you create spaces in there. I mean, you create spaces to pause. I love moments like these. And I just want to— Maybe my final question could be quite the architectural one—it is about the significance of these kinds of spaces. Because I do think, of course, text is something that is fitting for the form, but then there are really moments for a reflection, and I’d maybe just like to talk about that.

EVYeah, breath is really important, I think, in any medium. So I feel like, you know, when I work in film, I feel like the pauses are very important. Just like when you’re singing, the pause is often more important than the note. You know, it’s the space between the notes. When I used to play music, that was the thing that was drilled into me when I was on the bandstand as a teenager: It’s the space between the notes that matters. Anybody can play notes, but you gotta own the space. And that stayed with me.

And so, in a volume that’s full of type and text, you need to have space and breath to even, just to take in what you’ve just read. And even if you’re flipping through it, it creates an experience of space. And it’s like the notes and the space between the notes is present. And then, in this particular issue, there is quite a specific editorial point that we’re trying to make in those spaces, where we offer this kind of lyrical overview of the text. And maybe I’ll read that, just as a way to end this conversation, ’cause maybe it brings together many of the threads we’ve been talking about.

And so we open by saying: “In an unraveling world, we must begin to reweave a relationship with the Earth by examining and reimagining our most foundational ways of being. And what is more foundational than Time? Separated from the very fabric of the cosmos, the vast mystery of Time has been distilled into a tool of control. But what happens when Time slips the yoke, unbinds from the mechanical, and becomes free from the finite, the systemized, and the linear? What kind of Time listens and moves in tune with the Earth, travels not in a straight line, but a circle. The stories in this volume explore these questions and invite us to imagine a Time and space where ecology, culture, and spirituality are again woven together.”

So that’s the first space that we offer. And the second one: “Time begins to open us as a living force, a cascade of processes, an interplay of relationships.”

And the third: “Time moves at different speeds in many forms in all directions, beneath us, through us, within us. If we recognize a different kind of Time, can we come to dwell within it?”

And then the last offering, which closes the book: “Through the mystery of Time, we remember that we are of the Earth. A part of the endless turning of the wheel; the continuous rhythm; the call and the echo.”

MMThank you, Emmanuel. And, yeah, thank you so much.

EV Thank you.