The Heart of Requiem

Susan Murphy Roshi is a writer, filmmaker, radio producer, and founding teacher of Zen Open Circle in Sydney, Australia. Since receiving dharma transmission in both Diamond Sangha and Pacific Zen lineages, she has been leading regular retreats around Australia and teaching a country-wide sangha that extends internationally online. She is the author of Upside-Down Zen; Minding the Earth, Mending the World; and Red Thread Zen. Her latest book is A Fire Runs Through All Things: Zen Koans for Facing the Climate Crisis.

Terry Tempest Williams is the author of numerous books, including the classic in environmental literature, Refuge: An Unnatural History of Family and Place; Finding Beauty in a Broken World; The Hour of Land: A Personal Topography of America’s National Parks; and Erosion: Essays of Undoing. Her latest book is The Glorians: Visitations from the Holy Ordinary. She is the recipient of a Lannan Literary Fellowship and a John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship, and is currently the Writer-in-Residence at Harvard Divinity School. Terry divides her time between Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Castle Valley, Utah.

Emmanuel Vaughan-Lee is an author, Emmy- and Peabody Award–nominated filmmaker, and a Sufi teacher. He has directed more than twenty documentary films, including Taste of the Land, The Last Ice Age, Aloha Āina, The Nightingale’s Song, Earthrise, Sanctuaries of Silence, and Elemental, among others. His films have been screened at New York Film Festival, Tribeca Film Festival, SXSW, and Hot Docs, exhibited at the Smithsonian Museum and London’s Barbican, and featured on PBS POV, National Geographic, The New Yorker, and The New York Times Op-Docs. His new book, Remembering Earth: A Spiritual Ecology, is forthcoming from Shambhala in summer 2026. He is the founder, podcast host, and executive editor of Emergence Magazine.

Drawing on their Volume 6 essays, Terry Tempest Williams and Susan Murphy Roshi contemplate the paradoxical nature of a requiem for the seasons, revealed through an acceptance of impermanence, a love for the burning world, and moving with flock consciousness through this time of ecological uncertainty.

Transcript

Emmanuel Vaughan-LeeTerry, Susan, welcome to the show. It’s wonderful to be able to speak together today.

Terry Tempest Williams Thank you.

Susan Murphy RoshiYeah, good to be here.

EVLSo for our new “seasons”-themed edition, we invited you both to write on the theme of requiem, which is one of the three main themes explored. And it was really a space to acknowledge and pay tribute to what is vanishing or has been lost as the familiar cycles of the seasons begin to unravel as we put Earth under greater and greater duress. And Susan, you wrote a brilliant piece about haiku and its relationship to the changing nature of the seasons. And Terry, your essay spoke to the loss unfolding in Utah’s Great Salt Lake. And I’d like to start our conversation by asking you both about requiem: what a requiem for the seasons means to you, not only as a response to the physical loss of seasonal moments, but to the fracturing of relationships we’ve long held with the seasons and the landscapes they shape. So maybe, Terry, I’ll come to you first.

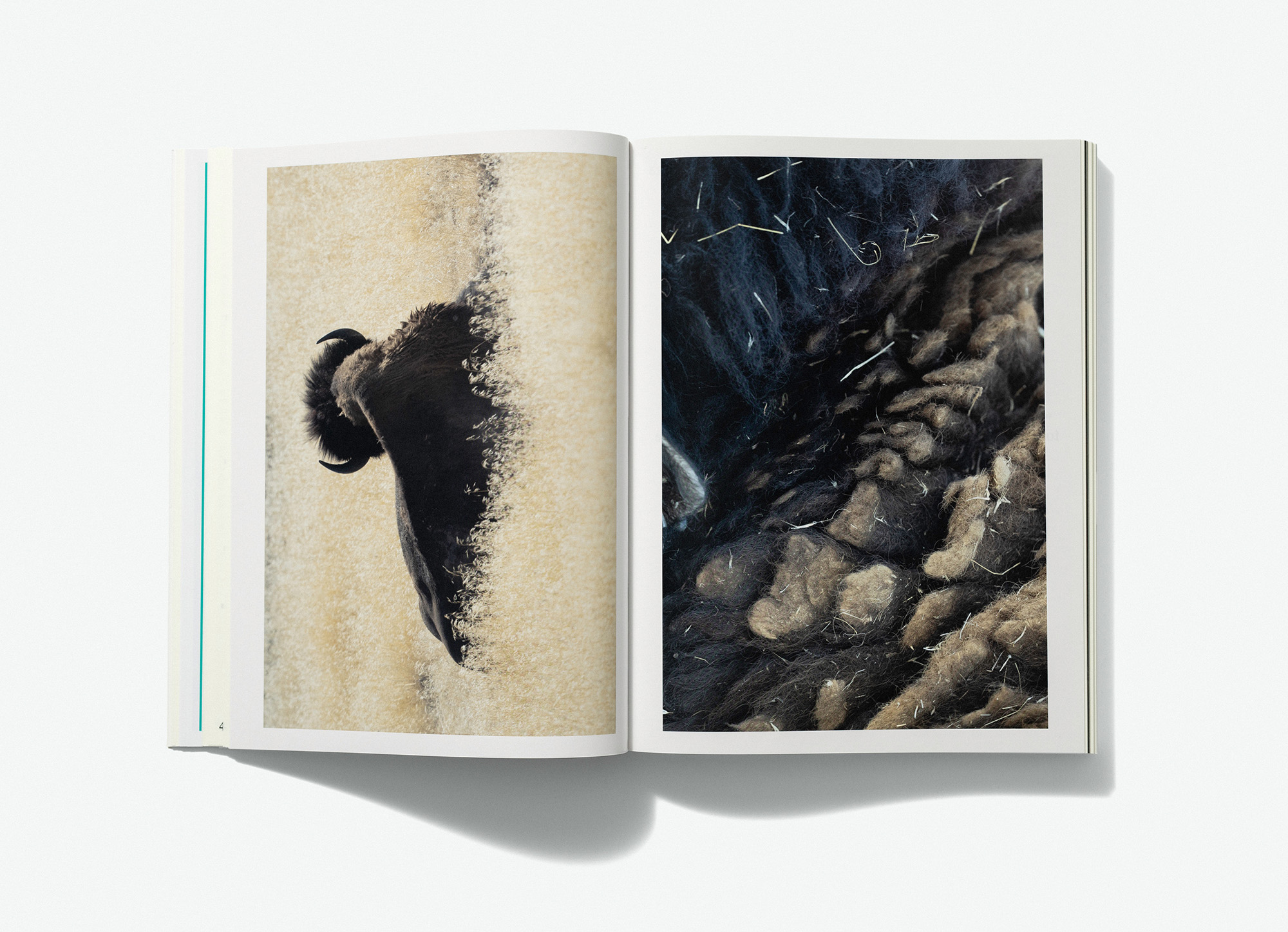

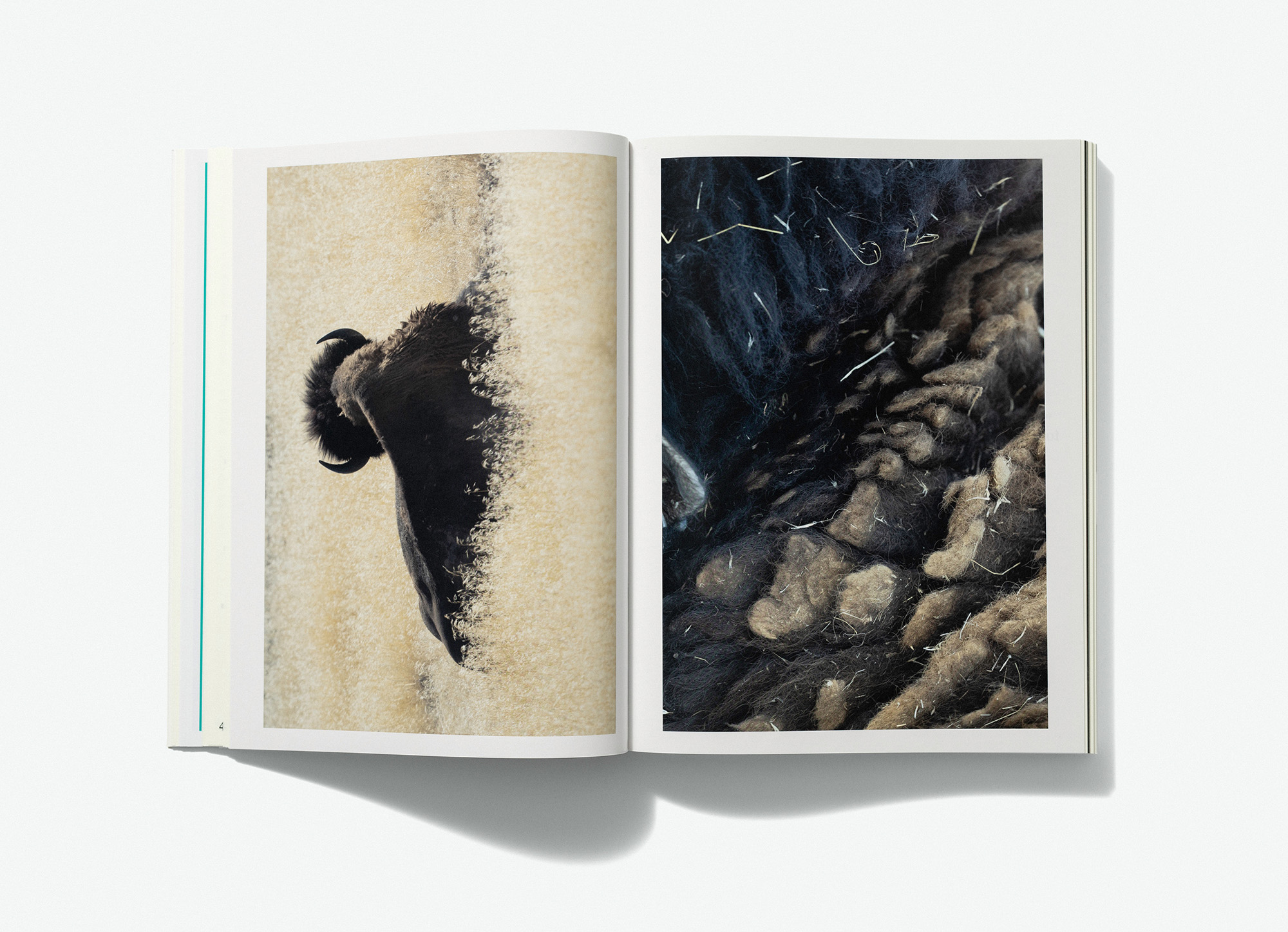

TTWWell, I think both of us took on the notion of requiem, of remembrance, and both the fluid nature of change as well as the terrifying nature of change; and as Susan reminds us again and again in her beautiful piece, the power of impermanence—but also the opportunity to seize this moment and be really present. I know, in my essay, I focused on Great Salt Lake, which is in retreat, which is in a state of vanishing. I can’t in all conscience and consciousness say that she’s dying, because she’s part of a much older story and we are just a blink, if you will. But nevertheless, it’s painful to watch and realize what’s at stake: twelve million migrating birds dependent on her; the bison, this powerful remnant herd that remains on Antelope Island; and close to two million people. And the ecosystem that we’re a part of is at risk because of the toxins that the dust lays bare in this moment.

EVLSusan?

SMRYeah. One thing that struck me is that there’s a whole sense of change moving through us. And how do we do that, you know? It’s not happening to us. It’s moving through us, as you say so beautifully, Terry, with that image of the bone—the bone through which things can move. So there’s that sense of a requiem as a memoriam, in a way, or at least taking deep notice of something that is happening, has happened, but is happening. And also at its heart it’s a kind of celebration of all that is passing through, even as it’s passing through. I say “celebration” because when you pay attention you are, in a sense, already holding it in your heart. And so what seems to me to sort of synchronize between our two pieces is that sense of approaching impermanence without resistance, because requiem is acknowledging what is passing through, or even being lost, but not as something apart from us, as something that, in a sense—

There’s a beautiful thing that Dōgen, the wonderful thirteenth-century Japanese master, said. It was actually as part of a piece called Advice to the Cook. He said, “Turn things while turning with things.” So, that gives you such a strong sense of what is possible right on this creative edge of uncertainty, which is where we live, let’s face it. To be able to engage with that without trying to coerce it, to be able to engage with that as being finely attentive to what is happening, as a means of finding that creative edge within it at every point, finding the participatory edge as well. This is not to deny loss and sorrow and grief, but there’s love inside grief, you know? Grief is the very proof of the depth of love. So that urge to love.

Terry, I love the fact that your piece is quite erotic in a great way. You know, it’s saying: I can move into that body, I love being in that other body—that interspecies kind of sense of fluidity. You actually called it “species fluidity.” I think that’s a great idea, a saving grace, you know, to see other creatures with that kind of— We’ve always been great mimics as human beings. But to see it as the invitation to go down inside me and come up inside that creature. Why not, you know? That’s our human thing.

EVLWell, you’re speaking to intimacy there as well, and that’s something that is very present in haiku, this intimacy with the seasons that is evoked, and something that’s been nurtured over four hundred years as haiku has become this form of expression. And you write about how climate breakdown is disrupting the work that these seasonal words, that create the intimacy that is present within haiku, do; and how they can bring us into a profound sensory experience of a moment in time. And, Susan, I wonder if you could speak a bit about this and what it might mean for this form of poetry, of haiku, through which we’ve long praised and connected with the seasons?

SMRWell, of course the seasonal reference is so important if you’re going to be located in time when you’re highly restricted in terms of the number of words. Haiku are right on the vanishing point of language itself, but totally present within that. So, the seasonal references are a way to anchor us in time and place, because every seasonal reference is going to bring place with it. It doesn’t just simply say “spring” and leave it at that. It’s what is happening in that very moment of spring, for example. So that intimacy. The thing that I love about haiku is that it’s very relaxed towards where it is and what is happening. And that allows a certain degree of presence that doesn’t have an agenda. It doesn’t have an opinion. It hardly has an “I” of self in front of it.

So the seasonal references are, of course, collected in vast compendia of the old kigo—seasonal references. So people would be able to just refer to one of those as a kind of anchor for the person reading or hearing the poem: an anchor in time. And those anchors in time and place are now, to say the least, disturbed. They are adrift. So the seasonal references that now have to bully their way into haiku, or oblige us to notice them and admit them, are harsh. They’re going to be harsh. They’re going to be floods. They’re going to be the lights going out one by one. They’re going to be the sense of the gaze of fire in the forest, the gaze of fire burnt into the forest. The sense of not stepping away, not turning away from exactly what’s happening—an engaged ability to not know what has happened; to be with it in the form, the intimate form, of not-knowing.

So I think that seasonal reference has always carried with it two things, in a way. It’s carried a sense of time endlessly moving—impermanence, but in the cyclical form. So it’s always been a deeply reassuring gift to say “season.” It sounds as though it will come round again. We are mortal, that’s a very sharp fact. But the roundness of the seasonal return, the cycle of seasons—that’s always been the thing that has sort of given us a kind of confidence, in a way, a kind of agreement, a decision that we can be here with some confidence. We can entrust ourselves to this place, which is eventually going to see our disappearance. So we can find a home in the seasons, and now that home is looking back at us and saying, “Really?”

EVLTerry, your essay, as you pointed to, revolves around the shrinking of Great Salt Lake, cultivating a response to what suffers and endures within its collapsing ecosystem from a place of profound relational empathy. And you write about how the truth of the lake’s “absence can bring us into a deeper understanding of its presence.” Tell me more about this relationship between absence and presence here.

TTWWell, I think of my mother. I can’t think of Great Salt Lake without thinking of my mother. And I can’t think of my mother without Great Salt Lake. I just turned seventy, and I’ve seen Great Salt Lake in its historic flood level, where it was right on the edge of the Salt Lake Airport, and I’m now witnessing Great Salt Lake in its historic low, where in many places all you see is a horizon of quicksilver—that’s it. And my mother, in the season of her death, I think she taught me very deeply about what Susan is talking about: of being with, of having the courage to not look away. Because as a young woman, twenty-eight years old, as my mother was dying I remember she was diagnosed with ovarian cancer, and she was going in for a second surgery to see if the chemotherapy had worked. And I remember holding her hand as we were waiting, and I said, “Mother, I know that you will be cured. I know you’re going to be fine.” And the doctor felt that way. We all loved her so much that we just knew that if we prayed enough, if we were positive enough, if we just thought of that hopefulness, that that would be the result. And Mother believed us. Who doesn’t want to believe that you will be well? That the treatments worked? And when the news came back, the cancer was still there. And I will never forget my mother looking at me in what I would call sacred rage and saying, “I could have handled it. Why couldn’t you? I dared to believe you.” And that was the most painful moment of my mother’s dying, because what she was saying was: You are not being with me in this process. You are wishing me away from this process. And I feel the same with Great Salt Lake—that in her retreat, I want to be with her as I was able to be with my mother through her dying process, which was really her living and loving.

And I remember in 2022, November, it was at her historic low, and I was kneeling at her edges, my knees in her waters, and they were magenta, they were red, because of the salt-tolerant organisms. So imagine a lake that looks blood-red. And I could see the pulse coming toward me, but more powerful was the pulse beneath the pulse going away from me. And that’s when I knew she was in retreat. And as a writer, I thought, what does retreat mean? Retreating from the enemy? Retreat meaning holding oneself in a healing grace? And can I be in that space of healing grace with her? And that’s been very powerful in terms of my own relationality to Great Salt Lake.

I have to say that Great Salt Lake, when I was a child, was largely ignored. You know, we made the obligatory trip with our mothers to go run into the lake, and we just as quickly ran out, because as children your legs are scraped and cut and the salt—we were screaming. And then we would drive home in the station wagons with our cousins and we were pickled, you know? We were white with the salt that was bleaching our skin. It was also a place of buoyancy, where you could float.

But now, when you talk about absence as presence, there is a love affair going on with Great Salt Lake, because we know that her status is impermanent, as is ours. And as Great Salt Lake vanishes, if we do not get water to her, so will our communities—both human and wild. So I think in her absence we are more present with her, just as in her absence she is more present with us.

SMRI just am really interested in this sense of absence in retreat, or presence in retreat. And obviously, I think obviously, it is love that is the presence part of it, especially in your story about your mother: you know, your longing for what was happening to be otherwise. It’s endemic to every human being—that longing to not lose the burning world. But at the same time, it is burning. I love the fact, something that Barry Lopez said close to his own death, in fact, where he, in “Love in a Time of Terror,” he said: “In this moment, is it still possible to face the gathering darkness, and say to the physical Earth, and to all its creatures, including ourselves, fiercely and without embarrassment, I love you, and to embrace fearlessly the burning world.” You know, I think that’s this kind of mystery at the heart of loss; that this huge presence becomes available in that space of loss.

TTWAnd I think even in the midst of watching so much of what we love go— You know, I live in the American Southwest and with this present administration, they’re talking about selling off our public lands, our public commons, if you will. The Endangered Species Act—they would love nothing more than to gut it. In my piece, I talk about how one of the political figures, who has overseen Great Salt Lake legally and with the legislature, et cetera, said to a group of our students from Harvard Divinity School when asked what are you doing about the Endangered Species Act, with the Wilson’s phalarope and the eared grebe? And he said, There is no proof that the Endangered Species Act has ever saved a species. And just then there was this thundering. We literally felt the pulsing, thundering beneath our feet, and we all stood up instinctively. And then there to the east, we saw literally six hundred bison stampeding in our direction. And even the czar of Great Salt Lake turned to the students and said, “I stand corrected.” You know, the irony of that moment. If we don’t believe that the Earth hears us, if we don’t believe the thundering hoofs of bison on Great Salt Lake’s island aren’t in communion with what we are thinking and saying, we will be held to account.

EVLThere’s a depth and devotion of attention to what is unfolding that feels like a common thread in both of your essays and in your work. Offering one’s attention becomes an act of mourning and honoring, and it really feels like it can be a way we can begin to be present with these things simultaneously. And, Susan, haiku so elegantly brings us into a certain space of attention towards the seasons with its essentialism. And you write that there’s a built-in “participatory love for the physical Earth” that directs attention “to some radiant fact,” that all the while is never encumbered by “knowing,” which I really loved. And I wonder if you can talk a little bit about what you feel can happen when we truly offer our attention at this time without trying to control the meaning of what we are seeing and experiencing?

SMRWell, the first thing that happens is you are present—more present. That’s the first thing. And the second thing, I guess, is you start to notice. You start to notice. I sometimes ask my Zen students to spend a good six minutes with a single leaf. And they just must stay with that leaf for the good six minutes and watch it become as mysterious as it truly is, and watch themselves in that process become as mysterious as they truly are. Now, a haiku can be a really fleeting kind of thing. It is a tiny kind of spark of the ongoing fire of where we are, but fully received. Because that person, if it’s a good haiku, does not elaborate the self in any way—because it’s not like it’s happening outside the self, but it is completely with the self. The self is a participant. This participatory presence is the gift of haiku. And that haiku then brings the reader or the listener back into exactly the same complete congruent moment where something became sort of indelibly visible for a moment and felt.

You know that title that I gave the piece, Alive in the Skin of a River—that has such a strong sense of: whose skin is it? The river’s skin? The person’s skin? You can’t say. You know what it’s like when you jump into a cold river that’s flowing. You are inside the skin of the river, the river’s inside the skin of you. It’s impossible to separate. And so that is kind of the gift of haiku: that it just is one—completely present, but not just present. Because it’s disarmed as to knowing. It is not attempting to place anything onto that moment, and that’s what lets the core of reality be present. Because it’s utterly mysterious—the core of reality. And that’s what makes a haiku worthwhile, makes it memorable, makes it something that you take with you. It becomes a companion for life if it’s a really good one, because it has opened you up, even rearranged you, the way a great painting does. You know, you stand in front of it, you let it rearrange you. A haiku does that, I think. And it rearranges you back into the wholeness of what this is, where there’s no real gap between me and all of this. There’s no gap. That’s the core of reality that I’m talking about.

EVLTerry, on this same question of attention, your story points towards finding a certain space of presence amid great change, writing that both Great Salt Lake and the bison surrounding it are “bodies of imperceptible stillness” amid a deepening story of change. Tell me more about what you mean by this stillness.

TTWYou know, as I was reading Susan’s piece, I thought, could it be that Great Salt Lake and bison are their own embodied haikus? I loved when you wrote, Susan, “a plain kind of wonder.” I mean, they’re so sophisticated, and also just the shape of them—the physical shape of Great Salt Lake, the physical shape of a bison. I do think there is an erotics of place that we deny, that we’re fearful of—call it pansexuality, or I should say pen-sexuality. Maybe it’s with a pen as well, our love of writing. You know, writing is an act of attention. I love how Simone Weil talks about how attention is a prayer. There is this sacred reciprocity. They are not other. I love how, Susan, you talked about Satish Kumar talking about, You are, therefore I am. I feel that the bison are, therefore I am. And so I can imagine this erotic relationship, meaning that we are one with, on the same tilted planet as you were.

It’s embodied knowledge. It’s embodied presence. It’s being attentive. When I was out at Great Salt Lake recently, the grasses were imprinted by the body of the bison, and I found myself— I wanted to know what that smelt like. I wanted to know what that felt like. And I found myself just—call me crazy—but in this fetal position where the bison laid and I could smell them in the same way that I can smell the lake and know that buoyant hand that lifts one up. I remember as Great Salt Lake was retreating, I just had to be in that water, and I took off all my clothes and I just walked. I just entered the water and walked and walked and walked. I must have walked well over half a mile, maybe longer, until the water was to my chin. I was so overcome by the softness of that water, the glimmering nature of that water around me. I lost my mind and I dove in knowing fully well what would happen to my eyes. And I was blinded. I literally could not see. I did not know what direction I was in.

Then I could hear where the waves were licking the salt. And as I came back, all of a sudden this wave pushed me back and then scraped my back against what would be likened to a coral, which are the structures that create the tufa. And my back is scarred from that moment in the low waters of that, and it was like a scarification ritual.

What am I saying: it’s beyond words. As a writer, I feel mute around such powerful presences as Great Salt Lake and bison, both in retreat. And yet, I was reading Susan Orleans’s memoir, and she was saying there’s two kinds of writers—and I think it can also be two kinds of people, not to classify or create a binary—but it was interesting, she said, there are those writers who feel they have something to say, and there are those writers who feel that the land or the subject that they’re working with have something to share with them. And I always feel the latter as a human being on the planet. Whether it’s Great Salt Lake, whether it’s the bison, whether it’s the clouds, whether it’s the fire and the flames—they have something to tell us. And to me, attention is not just visual but: What are we hearing? What are we tasting? What are we smelling? What are we touching? What are we seeing in the wholeness of a relational stance?

SMRI think often you have to close your eyes, as in a river or a salt lake, too. Close your eyes before you can start to pick all of the rest of that up; because our eyes are so directive, but everything else is receptive. Hearing is receptive. Touch is receptive. Only the eyes go looking for things. The ears don’t, they just receive.

TTWAnd, Susan, I loved how you brought that word “reconsecrating.” You know, what does that word mean in the face of requiem? To consecrate, to reconsecrate, restore something, to reconstitute it. The act of reconstitution. I think not only does our attention create a reconsecration, but I think their presence creates that reconstitution within our own souls.

SMRYes. And what you were talking about reminded me a lot of the Indigenous Australian sense of Country, because Country is so removed from thinking about a place. It is actually thinking along with the place, or letting the place think along with you. And that’s a collaborative, that’s a very “you are, therefore I am” kind of position to take to the place itself. Because Country does not refer to landscape or countryside. It refers to something far older and deeper—the original ancestor, really. The oldest and most venerated ancestor is the very place where we are. And that Indigenous sense of, every act of attention is joining with something that is, in a way— It is reconsecrating, because it actually lets what is reach us. It’s in plain sight or plain reach at all times, but most of the time we’re completely other than with it. We are in a kind of strange extraterrestrial state. Here we are, we’re like extraterrestrials most of the time.

TTWYou know, I think about the synchronicities that occur when the inner and outer landscape merge. I remember early on in our marriage, I came home from an assignment, and Brooke—it was in those days when you could be met at the airport rather than security—and he said, “Terry, I’m so tired. All I get from you is bones.” And we went to a restaurant and we decided to burn our marriage certificate. We both had been married in the Mormon temple. And I remember this waitress came by and said, “May I help you?” And Brooke said, “We wish you could.”

Anyway, the next morning we took our marriage certificate—my father’s name on the left, Brooke’s father’s name on the right, the patriarch in the center with the spires of the gothic temple—we went to the edge of Great Salt Lake. White landscape. Both of us had matches. I burned one corner. Brooke burned the other. And we just watched our marriage certificate go up in flames and the black cartwheeling ash moving toward the waters. It was emotional. I wondered what would become of this ritual.

And suddenly we looked up and there in front of us was a pink flamingo. They are not indigenous to Great Salt Lake. We couldn’t believe it. It was like all of a sudden the attention was off our marriage. It was like, look at this pink flamingo phoenicopterus ruber—the phoenix right before us. Where, how, why? And we realized, you know, we were the flamingo. The flamingo had met us in this moment of transformation. Turns out this was known as Pink Floyd, it belonged to the aviary, it had escaped. In many ways, we were escaping the prison of our own conditioning. But I think these things happen. They’re commonplace. Again, it’s that plain kind of wonder that is all around us, if we are open.

EVLEarlier you spoke to impermanence, which is something that the seasons can always teach us, constantly. But especially in this current moment where the seasons are shifting so drastically, impermanence becomes, let’s say, harder to ignore. And Terry, you allude to this need in your story with the image of the hollow bone, which is the title of your piece. And I wonder if you could talk about this, and how, as you write, we must become “a vessel that change moves through.”

TTWWell, it’s really to the credit of a dear, dear sister of mine, who is a Ute, Mountain Ute: Regina Lopez-Whiteskunk, whom I love. And it was she who said, “Be a hollow bone. We can be a vessel that things move through.” Those aren’t my words, those are her words. And I think that’s such a powerful statement. What did she mean? I remember in that conversation, “we can be a hollow bone.” You know, can we allow the world, the wind, life to move through us and to not be staid or stuck or stagnant? And I think that’s another gift of Great Salt Lake—the winds howl there, even as the bison take on the stance of stones. What does that mean in terms of—

You know, I think about that beautiful haiku that you gave us from Issa: in the world of dew, and yet, and yet, going back to, again, that sense of stillness; the hollow bones of birds that allow the air to move through to allow them to fly; the stillness of the bison to take on the countenance of stone to endure those raging winds and blizzards, including desperate heat in times of drought. And yet, and yet. So again, these seemingly contradictory stances, I think, actually create a cohesion of adaptability.

SMRThat cry of and yet in that poem of Issa, he had lost his most beloved daughter, two years old, to smallpox at that moment. And that cry and yet sits totally along with, even inside: you know, the world of dew is the world of dew. Obviously that’s a very traditional acceptance of “change is us.” We cannot step outside of impermanence. Nothing is ever finished, and that means loss is perpetual, in a sense. Both are true at once. But when he says and yet, it’s not just a human cry of “it’s impossible,” like losing your mother, losing a child—impossible, at a certain level, it’s vehement protest—but it also is a completely open state. And yet. It’s not foreclosed. It doesn’t foreclose on a single thing. It’s actually the intensity of the love inside that and yet that leaves a completely open, the most open, state right in the teeth of a huge loss.

That’s where we are. That’s the only live place that we can be in now. We can’t turn our backs on the perpetual draining of the color, or the threat of the draining of the color. You know, for me, when I say that I think of the Great Barrier Reef. As a child, I lived alongside the Great Barrier Reef, the largest single organism on the Earth, and it was just an impossibly wondrous treasure. I can’t believe what’s happening, to watch the color being drained from that, the life being drained from that. You know, Hakuin called it “a black fire burning”—this impermanence—“a black fire burning with a dark, gem-like brilliance.” And that just seems to me to be the place where we are.

And unless we have that fierce love that can include ourselves— We can’t just sit and hate ourselves as human beings. We have to say— The love has to— We have to be able to love ourselves, even including ourselves, every creature on Earth, fiercely and without embarrassment. We have to cry. We have to be unembarrassed to weep and to cry out “And yet!” as a kind of cry, but also to hear that in that “and yet” there is a completely open space. It opens up completely with those words. It’s like a gate you can walk through.

TTWAnd it feels—back to the hollow bone—the hollow bone allows for the whistle, for the music to come through, through breath. But the hollow bone only exists in our hand because of death. That bone was a part of a body in place. And so again, it’s the paradox that is the practice.

And Susan, I feel your emotion when you talk about the Great Barrier Reef. And I’ve never seen it, but I think about it, and I will now see you in it and that green leafy dragon. Once I saw that at the aquarium, and I just thought, I wonder how they’re doing: the green leafy dragon that is a seahorse. It’s not an abstraction: It’s real, and I hear it in your voice. And I think for all of us to claim and reclaim and to, again, reconsecrate the places that we call home, the places that helped us imagine another way of being, even in another body of another species, is part of, I think, the acts of grace and the hands that create the actions that will follow that love.

EVLBoth of you explore the need for us to embrace the unknown in your work. And Terry, you’ve explored this at times through faith and how faith can be an act of becoming open to the unknown, of honoring mystery. And Susan, you’ve written extensively on the power of the not-knowing mind to shift our consciousness. And as the seasons become more and more unfamiliar, we lose an understanding of what was once the most fundamental and consistent expression of what the Earth looks like, or even is, as you alluded to earlier—that bedrock of experience becomes less solid with this change. And my question for you both is what do you think this deepening unknown that is now the seasons can invite us into? Terry, maybe I’ll come to you first.

TTWYou know, I just realized, I don’t think in a linear way, Emmanuel. So I feel like I’m just this impressionistic voice right now.

EVL[laughs] That’s okay. I like your colors and gestures.

TTWBut you’re touching on such deep things. And I think about my brother, who was an addict and suffering from depression. And I remember one of the last walks we took before he took his life, and he said to me—we were looking at the sunflowers—and he said, “I wish I could face the light. I understand darkness, but I wish I could face the light.” And I’ve never forgotten that. Sunflowers follow the sun. And then we both ended up in this conversation: Can we love ourselves enough to change? And I’m both haunted and inspired by that question. Can we love ourselves enough to change? Can we love Great Salt Lake enough to get water to her? Can we love bison enough to allow big open spaces to remain without development, in places like Montana and elsewhere? As a species, can we love ourselves enough to allow other species to live, not die at our desires and needs? I think it’s those questions that keep me up at night.

My great grandmother always said to us: Faith without works is dead. So that question, it’s not so much what do we do, but how do we engage? Because I think if we’re present in these spaces that we love so much that have shaped who we are, and who we’re a part of, then we will know what to do. We will know what acts are appropriate, because we’ve never been here before in this way. And I think it’s acts of imagination, acts of compassion, acts of desperation, and acts of rage that will determine our future. And in community, I might say.

SMRYeah, in community, for sure. It takes all of us. It takes every eye on the matter, everyone in the boat, so to speak. I think also, I was thinking as you spoke of, you know, that shift that Satish Kumar brings forth from upturning I think, therefore I am, which is a kind of, it’s like everybody as a sort of self-contained capsule thinking and looking out from inside this capsule. The shift to you are, therefore I am—this is an utterly live space between the self and the other, to the point where it is the space itself that is the matter, the great matter. It’s the space between that is where every kind of truly creative possibility arises—the space between self and other. And it is, of course, the place where the self and other dissolve. They dissolve into the and— you and me. No, it’s the and. It’s all and here. There’s nothing going on in any ecosystem except and, ultimately. That’s what holds everything together.

TTWI love what you just brought up, Susan, about the space between, that everything happens in the space between. And it makes me think of flock consciousness, that when you’re on the shores of Great Salt Lake, you see these wonderful flocks of shorebirds, whether they’re sandpipers or the phalaropes or red-winged blackbirds. But you wonder— And you see it in the murmurations: How are they making these beautiful configurations and these deft moves without crashing or hitting each other or falling out of the sky? And I think what’s the counterpart to us as human beings? What would our flock consciousness look like? Not blind obedience or a flock of sheep, but really that kind of elegant movement on behalf of something larger than ourselves, to be swept away in that moment and create that kind of beauty and movement of air.

SMRWithin the immediacy of two people together, we entrain to each other. In fact, we entrain to the people around us. So if our kind of energy is “earthed,” you know, if we’re present enough, everything around us entrains to that. I think I’m just trying to get to the murmuration. How does that thing— It happens, of course, with fish, schools of fish, as well, and the way that they take turns being on the outside, the dangerous outside. They move in that utterly one body, you know, all-beings-one-body, kind of way. Somewhere in there, there’s the chance for human beings to get past ourselves and to say: All these amazing forms of life, including the planet itself, you are, therefore I am. It’s just such a more interesting place to be, apart from anything else, not in that kind of landlocked sense of, I think, therefore I am; constantly making ourselves up in a kind of pathos. The pathos of this, in the end—so striking.

TTWEmmanuel, as a filmmaker, when do you feel that sense of movement, of oneness, with your subject and medium?

EVLWhen you’re not thinking and you’re just responding. I don’t think there’s much difference between the haikus’ intended result and any real artistic moment of letting go of the self and allowing what will unfold, unfold. So in your writing, that comes across so poignantly, Terry; and in yours, Susan, too.

And I was thinking about this sense of celebration that you’re also speaking to. Because there is this urgency, there is this loss, but there is this tremendous celebration. And that’s been kind of, I guess, spoken to around the edges of this conversation in your responses: that there can’t just be witnessing loss or being attentive to the changes, but there is celebration in that attention. There is celebration in what the loss is revealing to us, that Great Salt Lake is inviting us into.

And Susan, I have a quote here. You wrote about how haiku is not just a glimpse or an image of the universe, but “just the universe, plain and immediate, inhabiting the poet, the reader, the stone wet with rain by the side of the path, the autumn moon, the tremor in a hand, a leaf turning bright dark bright dark as it twirls to the ground,” which is so celebratory. And it’s a beautiful evocation of interconnectedness that you’ve been speaking to—the both of you have been speaking to—about a pureness of being in relationship with the Earth that we can experience with the seasons, even amid loss. And, I guess, maybe the question is for really the both of you, which is that holding that sense of oneness and the loss and not letting the apathy and the feeling of the overwhelming grief pull one away from the attention needed to be in a space of celebration. I’m curious about this, because it’s what you both speak to in different ways in your work.

TTWYou know, I keep thinking about what Susan said about the relaxed gaze, which is so powerful—moving with and being present with what is happening. And I was realizing, in the piece that I wrote, I talked about the depth of a bison’s gaze. It’s like the universe is in the blackness of that eye, the depth of that eye. And what does it mean to be able to focus, to make eye contact with another species in a gentle way? We know that with our dog kin or cat kin. But there’s something to me also in how we look in one another’s eyes.

I realize with many of my students, most of their lives are on their phones texting or on their screens. And we meet in a cafe for an hour at the beginning of the semester and also at the end. And there’s nervousness, because how do we engage now when it’s spontaneous, when there isn’t a script, when nothing is wanted but just to get to know one another? And the moment happens when you realize you both have this soft gaze looking deeper into one another, listening, being present. And then something breaks open, you know? And intimacy is there. And I feel that this is something not just with other species now that is so essential, but with one another.

I know in our country, in the United States, right now, people are terrified of each other. I just had a friend speak to me about—it was the first time that she could really talk about what it feels like to be a Jew in America right now, and how many friendships she’s lost because of her own feeling of anti-Semitism. And I spoke to her about my concerns about Gaza. We’re dear friends, and it was the first time we were able to really have that conversation and realize we both had common ground. And it was in, how do we feel the pain of one another and respond with that deep compassion without blocking each other’s views? I’m not articulating it well, but it strikes me that that relaxed gaze, there’s something for us to really sit with. Where is our gaze right now? And what is it? How is it being reciprocated?

SMRIt just struck me when you were asking the question back when, Emmanuel—the word “season.” I mean, aren’t we being asked to season into change perpetually? I mean, that is a seasoning. If we’re looking for the process by which we become and are able to move with what is happening—when we do that, we are turning with it, but it’s turning us as well. It’s changing us. People are changing in front of our eyes. The human being is changing in front of our eyes. Even as a proposition, you know, what is it? Where does it begin and end, technologically speaking, and so on? Who knows where this is going to go? That’s one of the great and yets. But at the same time, we can’t ignore the fact that we are being—I don’t want to say conditioned, I want to say seasoned, mellowed and becoming—being obliged to become a fit with what is happening. There’s no choice. We have to do it. It is doing it to us. We are—I think, I hope, I pray—that we are becoming more equal to our circumstances, because we have to. We have to find our way into being the response to the call. And I think that every kind of painful thing that happens is part of that seasoning.

EVLI want to maybe end our conversation by giving space for the liminal, because I think that’s very much the time we’re in, where there is something new that can emerge in the midst of the unknown. And, Terry, you end your story with an image of the Black Moon, the dark unseen phase of the lunar cycle. And you describe it as a time of introspection before renewal, a silence between cycles, which I loved. And it feels like you’re suggesting that this requiem is not just a mourning, but it’s also a liminal space of necessary darkness before emergence. So I wonder maybe to close our conversation, if you could both speak to this? How you feel requiem can also be approached as a seed of something new?

TTWThat’s such a good question, Emmanuel. I think of Shinran, the Japanese Buddhist monk, who said, “This happened. Now something else can occur.” I feel like this has happened. This is happening: climate uncertainty, global insecurity. Now something else can occur. So I think it’s a time of tremendous creativity—an opportunity to rethink our place on the planet, to rethink what our communities can be, who our communities are, and what we can do together in that beautiful spaciousness, the flock consciousness we were talking about. And that, like the eclipses that we’ve been seeing all over the world, that continue to bless us with that moment of totality, of darkness, and then the incoming light that is inevitable—I trust these processes. I truly trust these processes. And you know, Susan, when you write about koans, and especially with fire—that’s another conversation—but I would love to just hear where koans fit into these closing thoughts that Emmanuel is asking, because somehow that feels like a haiku as well. And I know nothing about koans, but your work has touched me deeply in the relationality of koans and climate.

SMRLook, a koan is actually a statement from a place of wholeness with all that is—the absolute depth of reality as well as the infinite variety of the relative world. It’s also very plain; a koan is not fancy language. It’s not highfalutin spiritual language at all. It’s very mundane. It is exactly where you are. It’s a conversation. It means “public case.” You could say that what the Earth is presenting to us right now is a severe public case. Nobody can avoid it. So a koan is a question or a proposition or a statement that can’t be approached with a discursive mind. It just does not touch it. You have to allow all of the ways you would approach it, all of the engineering devices you have at your disposal—you have to drop them one by one. Stop bargaining and just be exposed to it in the most, I guess, unshielded form that you can possibly find. And then it starts to reach you, just as the sitting with a leaf for six minutes finally starts to reach you, because you have dropped away, dropped away, all of the kinds of ways you have ever attempted to situate yourself, usually protectively, inside this precarious life. So it’s natural to wish to protect your life and protect your sense of self and so on. That comes with having a sense of self, this mysterious business of a sense of self. But to let the self go, in every religious tradition, is the place of true meeting. It’s the place where everything, finally, can even be perceived, can be noticed, can touch us; and at that point, it’s a strange mixture of sorrow and joy. The sorrow is partly, how could I have ignored this so long?

Let me think if there’s a good koan for the Earth for us right now at this point. There is the one that is a little bit like the very question of what is this self, which is “What is my original face before even my parents were born?” So that’s deeply personal, deeply intimate—face. There can’t be something much more personal than face, that instantly recognizable set of features. You pick them out at a hundred yards; that’s the person. There’s that sense of face, and it is also that sense of interface with the world, with the Earth, with everything. But what is my original face—this deeply personal matter—before even my parents were born? So I guess that’s a way— Obviously, you cannot look for this personal face without deeply noticing the Earth Herself—you cannot—and every single part of what is being endlessly poured out for us so, so generously, so ridiculously generously. And so, that’s where we look for our original face, and that’s where it looks back at us and finds us. So, I guess there’s a koan for the Earth.

EVLWell, thank you, Susan. I was going to ask you if you had a koan to end on, so you preempted that. And I think the face that we have before we were born is a very apt one, because it’s a shared one. And so I thank you for that offering, and to be able to be in conversation with both of you today, and for your wonderful contribution to this issue and your work. So, thank you so much, and until next time.

TTWThank you, Emmanuel. Thank you, Susan.

SMRThank you both. It’s been such fun.