Mycelial Landscapes

Merlin Sheldrake is a biologist, writer, and speaker with a background in plant sciences, microbiology, ecology, and the history and philosophy of science, whose research ranges from fungal biology and the history of Amazonian ethnobotany to the relationship between sound and form in resonant systems. He received a Ph.D. in tropical ecology from Cambridge University for his work on underground fungal networks in tropical forests in Panama, where he was a predoctoral research fellow of the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute. He is a research associate of Oxford University and the Vrije University Amsterdam, the UK Policy Lead at the Fungi Foundation, Director of Impact at the Society for the Protection of Underground Networks (SPUN), and the 2025 Distinguished Visiting Fellow at the Center for Human Rights and Global Justice, NYU. His book, Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds, & Shape Our Futures won the Royal Society Book Prize and the Wainwright Prize, and has been translated into thirty-two languages. Merlin is also the presenter of Fungi: Web of Life, a giant-screen documentary narrated by Björk. A keen brewer and fermenter, he is fascinated by the relationships that arise between humans and more-than-human organisms.

Barney Steel is an artist and creative director of the London-based art collective Marshmallow Laser Feast, which creates transformative experiences that expand the senses, reinvigorate a sense of wonder, and deepen audiences’ connection to the more-than-human world. Barney’s multi-disciplinary art practice, which combines sculpture, installation, live performance, and mixed reality, illuminates the hidden natural forces that surround us.

Emmanuel Vaughan-Lee is an author, Emmy- and Peabody Award–nominated filmmaker, and a Sufi teacher. He has directed more than twenty documentary films, including Taste of the Land, The Last Ice Age, Aloha Āina, The Nightingale’s Song, Earthrise, Sanctuaries of Silence, and Elemental, among others. His films have been screened at New York Film Festival, Tribeca Film Festival, SXSW, and Hot Docs, exhibited at the Smithsonian Museum and London’s Barbican, and featured on PBS POV, National Geographic, The New Yorker, and The New York Times Op-Docs. His new book, Remembering Earth: A Spiritual Ecology, is forthcoming from Shambhala in summer 2026. He is the founder, podcast host, and executive editor of Emergence Magazine.

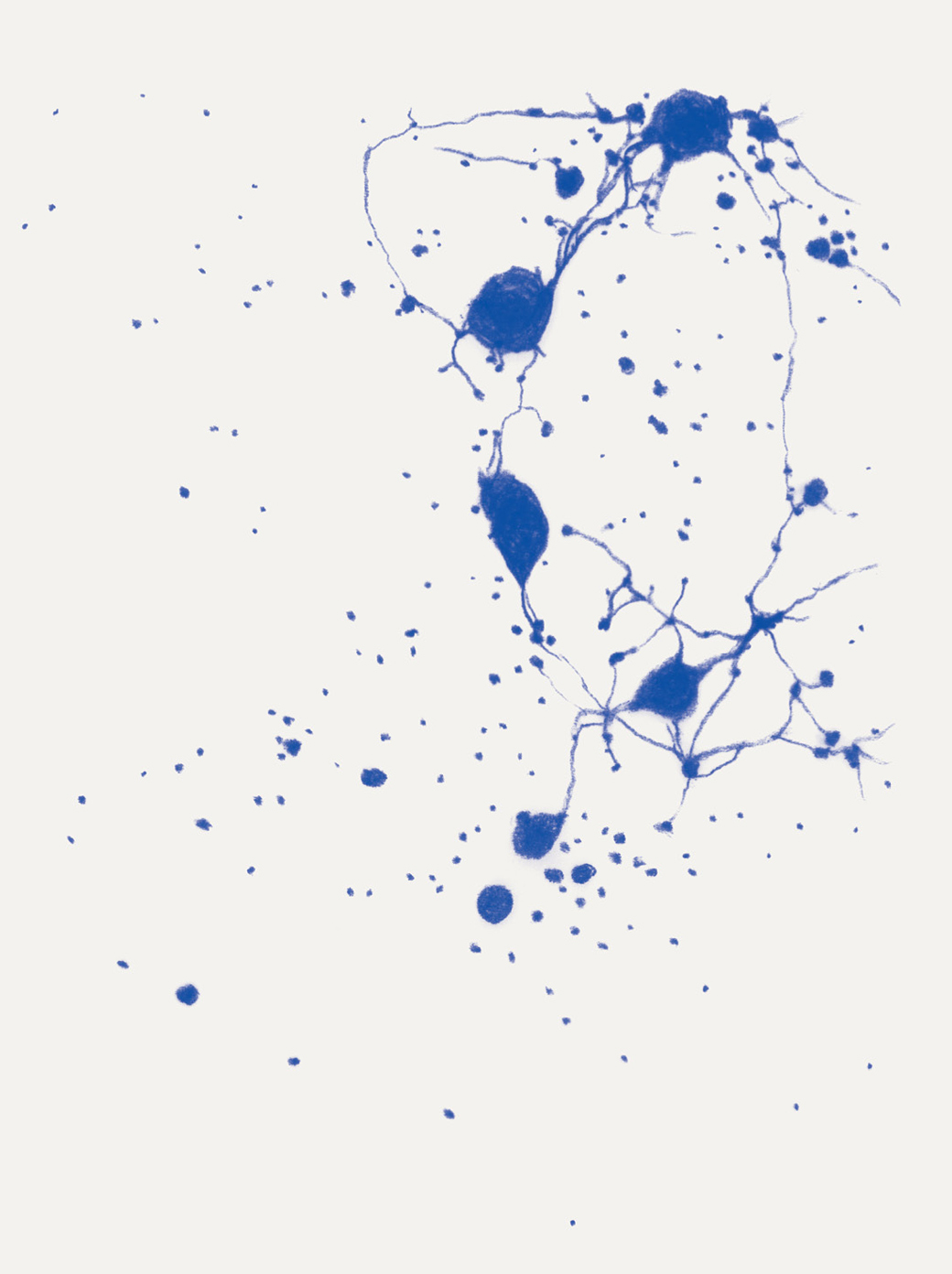

Madge Evers is an artist based in western Massachusetts who uses foraged materials to explore decomposition and regeneration. Blending photography, cyanotyping, painting, and mushroom spore prints, her works reference photosynthesis and the ancient collaboration in mycorrhiza. Her work has been published in Antennae: The Journal of Nature in Visual Culture.

Mycologist and writer Merlin Sheldrake joins Marshmallow Laser Feast creative director Barney Steel and Emergence Magazine founder Emmanuel Vaughan-Lee in conversation about the mycelial webs that infiltrate and sustain the landscapes we inhabit. Tracing these underground networks, they explore how fungi challenge our traditional conceptions of individuality, intelligence, and life itself.

Transcript

Emmanuel Vaughan-LeeI’m very excited for this afternoon’s conversation. This is the first time I’ve met Merlin, and I think it’s going to be a special conversation where we bring together mycelial explorations in the physical and digital realms.

I’m going to introduce Merlin first, although I think many of you know him and his work rather well. Oh, this is Smudge, who’s joining as well—this is Barney’s pup, who likes the limelight. [laughter and coos]

Merlin is renowned in the world of fungi. A mycologist and author with a PhD in tropical ecology, his work ranges from fungal biology to the history of Amazonian ethnobotany. His New York Times bestselling book Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds & Shape Our Futures won the Royal Society Science Book Prize and the Wainwright Prize. Welcome, Merlin. [applause]

Barney Steel is one of the founders and directors of the experiential art collective Marshmallow Laser Feast, whose large-scale installation is premiering as part of this exhibition. Perhaps many of you have been upstairs and seen this work. Barney and Marshmallow Laser Feast’s work has been presented at Sundance Film Festival, Tribeca Film Festival, South by Southwest Film Festival, and exhibited at esteemed institutions and galleries worldwide, including ACMI, The Barbican, Masachi Gallery, Fie Center, DDB Sol, Next Museum, and the Nobel Prize Museum, among many others. Welcome, Barney.

Barney SteelThank you. [applause]

EVBoth of your work is deeply entwined with mycelial webs and expresses how crucial these mycelial networks are to the ecosystems and landscapes we inhabit; and explores how fungi challenge our traditional conceptions of individuality, intelligence, and invites us to see and experience the myriad connections present in the more than human world. And I’d like to start our conversation by speaking about science and the arts, because both of your work bridges science and the arts, and each, in its own way, challenges the old, Western scientific practice as being a detached inquiry, where what is studied or explored is often reduced, cataloged, and systematized. And Merlin, in Entangled Life, you write that “science isn’t an exercise in cold-blooded rationality”; that “scientists are—and have always been—emotional, creative, intuitive, whole human beings,” something that is traditionally relegated to the arts rather than science. And I’m wondering if you could both speak to how consciously bringing emotion and awe and human response into acts of inquiry can open us to new ways of understanding the living world, and in particular the world of fungi.

BSI can kick things off. Okay, so photosynthesis—I guess that’s a good place to start. It needs a rebrand. It’s traditionally quite boring learning about it: black-and-white images, equations. But if you think about maybe being a water molecule and starting as a cloud, falling as a raindrop, getting sucked through the root of a tree, to arrive through this sort of greening, branching leaf structure—and you could use electron microscope scans of a leaf so that it has the detail of St. Paul’s Cathedral—and as you sort of glide towards photons smearing into probability waves, before all that energy zaps you and splits you in half, you could imagine that the experience of that would be more in line with an encounter with God, like the source of energy that flows through the food web. In a way, you can think of sunlight as weaving the web of life via this process. And so I think where we’re really engaging is, what would the experience of it be like? In the same way, to try and describe the flavor of an apple with words, it falls so far short of the richness of the sensation. So I think as technology evolves to engage multiple senses, where we operate with immersive experience is really trying to find that sweet spot of the awe and wonder in the experience of the observation. And obviously that exists beyond the limits of our senses, so that is why we collaborate with different scientists who are able to peer into these dark corners, into the wood-wide web, and shed light in those areas, which always, to me, is like the essence of awe and wonder—the stories that come out of that are beyond imagination a lot of the time, and I think that’s what sort of drives our work.

Merlin SheldrakeThanks Barney, thanks Emmanuel, thanks all for coming, and for waiting so patiently. I think this is such an important question, and what we call “the sciences” and what we call “the arts” are both, in my mind, derived from the faculties of imagination, of curiosity, of wonder, and of a sense of felt relationship both with the living world around us, and also with our own abilities to meaningfully experience that world. We think of these two things as belonging in entirely different departments of human life, and I think that this division is based on a centuries of bifurcation of the world into primary quantities—those things we can measure, those things we can understand through measurement and calculation—and secondary qualities, which are feeling-based things, which aren’t things, of course; feelings, like the flavor of something, the color of something, the sensation of cold water over your skin. The modern sciences arose out of this bifurcation, taking on as its job the primary quantities, those things we could measure, bracketing off the secondary qualities, the things we could feel, not because they didn’t exist or were any less important—although they were called secondary qualities—but because those were things that fell into the realm of the arts, those areas of human life that dealt with the feeling matters, the matters of feeling, knowing, and experiencing. So this bifurcation has created, I think, all sorts of confusing boundaries that we stumble over, mistaking them for natural features of our minds when, in fact, no—as you say, and as I said, I really do feel that scientists are, and have always been, whole and intuitive and imaginative human beings wrestling to make sense of world that was not made to be cataloged or systematized. And so I think we’d have a lot more fun if we could dispel this delusion that the arts and the sciences belong in entirely different departments of human life, because I don’t think that’s true. And I think we all live in what we might call “the sciences” and all live in what we might call “the arts” in different kinds of fluid ways all the time—just to be a living, functioning human. So, I’m excited to see the places where these boundaries wear thin, revealing their fragile underpinnings, and excited for all sorts of practices, and systems, and institutions, and events, and parties where we can start to explore the common source of these explorations, which I do think comes from a wonder, an awe, a curiosity, and a felt sense of relationship.

EVYou spoke about separation as perhaps one of the root causes behind these divisions, you know, between science and the arts, but it runs deeper. Perhaps the root cause behind many of the environmental challenges we’re dealing with is this separation, where we no longer view ourselves as part of the living world around us. And science has played a part in that, especially Western-based scientific models. And this exhibition is very much focused on the entanglement that we actually have with the biosphere; reminding us of that. And Merlin, you’ve written extensively about the ways, the myriad ways, that fungi is completely entwined with the existence of all life, and how we humans are so connected through this lens that the mycelial web offers us. And Barney, this kind of entanglement is something that Marshmallow Laser Feast has explored, I guess, since the beginning of your work, creating work that brings us into recognition of our dependency on an interaction with the more-than-human world. And, as I said, this entanglement is really a central theme in this exhibition. I’m curious to hear both your thoughts on the importance of emphasizing this entanglement as a response to the immense ecological destruction that we’re experiencing.

MSI think about the ways that the modern sciences are now talking much more about the relational aspect of the living world; that the world is made up not so much of individuals but of relationships between entities, which themselves are bundles of relationships. Like you, yourself, are a planet with regard to the legion of microorganisms that live in and on you and without which you couldn’t do what you do. Many of those bacteria might have bacteria inside them and viruses inside them. And larger viruses might have smaller viruses inside them, and onwards and downwards. So, the idea that this is a relational phenomenon is thankfully receiving more attention now through the careful work and astonishing vision of a number of scientists over the last couple of hundred years. And yet, this is not a new idea. This is really modern science catching up with what is a very, very old idea among humans—that we live in a living world, we are alive in a living world made up of intimate, reciprocal, dependance. So this feels more like a remembering that’s going on in the modern sciences than a discovery. And about time, too. It’s very exciting to see how this unfolds.

One of the things I spend a lot of time thinking about is, what comes first: the entities doing the relating or the relationship between the entities? And I do think it’s a chicken and egg question, but I also think it’s a fun chicken and egg question. I like chicken and egg questions. [laughter] (Some of my best friends are chicken and egg questions.) What I mean by this is that if we think about the relationships between the entities doing the relating, rather than the entities doing relating, then we end up in a different place. For example, when you draw, traditionally, you might draw a schematic illustration of a plant relating with a fungus, and you might draw the plant and the fungus and a sort of dotted line between them to represent their relationship. And this presumes that the plant and the fungus could independently exist without each other, when in fact the relationship between these two organisms, over hundreds of millions of years, has created what we now call the plant and the fungus. They exist because they have helped make each other. There’s a picture by the artist M.C. Escher of a hand drawing another hand, which is at the same time drawing the original hand. I don’t know if you’ve seen this. It’s a wonderful image. That’s, for me, a very helpful way to think about these entanglements, because it’s a co-creative, relational space where all the partners involved are helping to build the other. And that changes the way that I understand relationship and entanglement, because it becomes less about a series of dotted lines between individual entities; it becomes a kind of seething relational space, like a fabric that’s living and growing. And that’s why mycelium is a helpful metaphor for me to understand it.

BSOh, it’s hard to follow that jibber-jabber! Ooh! Okay. So I was thinking, a lot of our work is focused on the experience that connects, the experience of space between things, the relationship between things, and part of that is thinking about how maybe language creates a framework where the world becomes objectified. So you can point at a tree and that suddenly becomes a framework through which you experience and see a tree, but then when you look at it more deeply you realize it’s a web of relationships. The classic [example] is that you don’t get flowers without pollinators: the pollinators are an extension of a process, and they’re woven into dependency. So, it’s interesting to think about the full glory of what it is to be a human, and everything that we can sense excludes a huge portion of what could be described as reality. And I think scientific observation is able to draw light and reveal these relationships, and one, in particular, that we focus on a lot is breath.

One way we could do this—maybe we should all close our eyes for a moment and just take a deep breath in. [inhales] And out. [exhales] Just keep breathing deeply. And now imagine you can see a tree in front of you, but the oxygen has been made visible. And as you’re breathing in, you can see it leaving the leaves of the tree and just passing your nostrils and mouth, and it’s filling up your lungs, which also look like a tree. Imagine those particles as blue. In fact, you can sort of lean your chin forward and imagine that you can see those blue particles filling up your lungs and then hitting the bloodstream; it’s coming out at about three feet a second up into the brain. And now if you hold up your hand in front of your face, keeping your eyes shut, just imagine that you can see those blue particles branching through your vascular structure. And then they start to diffuse like river estuaries, eventually arriving at every cell within the body. To think about that completely weaves your interrelationship with the plant kingdom and the photosynthesizers. You can open your eyes again now. By simply making that visible, it questions the boundaries of where you begin and end, and it weaves you into a relationship that experientially creates a very different, intuitive understanding that doesn’t require language or the framework of science. And yet, you can use scientific techniques to observe that and make it real, and also the scientific understanding is what tells us that story in the first place. So, I think, in that sense, science could be seen as a way of revealing relationships and deepening our connection to reality. That’s the way I see it.

EVMerlin, you spoke about remembering that these models have existed before, you know, whether that’s Traditional Ecological Knowledge or perhaps just something primordial that is within us that needs to be revealed and has been covered over by hundreds, really thousands, of years of a certain modernization that took us out of a space of relationship. I wanted to speak to you both about ways of dismantling the way we conceptualize self and the individual, because that’s present in both of your work. And what you just offered, Barney, was perhaps a simple exercise to begin that process. I’ve actually heard you, in a previous conversation, say, “Where do you end and begin when the sunlight is under your skin?” And you just offered an example of that in how we breathe in relationship to a tree. I found what you just offered to be a fantastic prompt for softening the illusory borders we often place around the self, and opening the mind to the ways we are porous and entangled with the living world. And mycelial webs teach us this too: that no self is bounded; that every organism, including us, is deeply enmeshed.

And Merlin, you’ve talked a lot about this, particularly the fact that our bodies are, in themselves, part of communities—whether that be communities of microbes inside our bodies, or communities of trees providing us oxygen outside our bodies, as Barney just illustrated. And trying to locate the borders of the self within this is actually quite a bizarre thing to do, because how can we truly be an individual when we are in fact a “walking ecosystem.” So, I wonder if you could speak to this, perhaps starting with you, Merlin?

MSYeah, I find it a zone of deeply healthy confusion. I feel like if I’m not confused by that question then I’m missing something. And probably in my most pointy-minded, grumpy, sort of snaffy state, in which I shouldn’t be around anybody, I feel unconfused by that question. It’s almost like an indication that something is out of whack, if I think that question is straightforward; if I think that the boundaries of myself are evident, then I’m missing something. But also just to speak up for individuality, I mean there are lots of really important things about our sense as individuals. So many of the noble, just causes that have been fought for with great difficulty over the last few hundred years have been to do with issues like self-determination of individuals, individual humans, to make certain choices about their life; to not be despotically ruled over by others. I feel like there’s a lot of power in this concept of the individual in human life and culture that we definitely—well, I certainly—value and think plays a very important part in the way that we build togetherness. That being said, it is, I feel, a concept which has led us into lots of trouble as well, in that it likes to imagine ourselves as neatly separable.

And so it’s a funny one, to live in that balance between: well, okay, we need this concept somehow, and yet where does our faith in this concept lead us into trouble? So when you’re looking from a biological point of view at the living world, it becomes clear that the concept of the individual isn’t so much a natural fact but rather a category that depends on your point of view. If you’re looking inside your body—if you’re a surgeon performing an organ transplant, then you can see very clearly that this heart, or this liver, or this kidney, is a bounded organ that can be transplanted from one organism to another—and that’s an essential part of that perspective as a surgeon in that moment. And yet, if you stand back, you see, well, of course this kidney can’t function without the physiological connectivity of the body. It is made up of cells, which are produced in a developmental process from a fertilized egg, and that can’t be thought of as separate from the process of development that has led to this organism in the first place.

So that’s what I mean about what point of view you’re taking. I think that then leads us into some fun places when we try to understand the living world and the ways that we create categories and boundaries, because lots of the boundaries and categories that we make are revealed to be quite fragile, quite brittle, fragile categories. It’s very hard to police a boundary that you can’t locate. Lots of these boundaries have to be arbitrarily located in order to be policed. And a lot of this opera of human life gets played out along these edges, and so I value the way that the biological perspective and this perhaps more intuitive perspective can lead us to question those categories. I think they can lead us to healthier places. But also there are many ways to experience this sense of boundedlessness. I think that mystical experiences, which can occur, prompted and unprompted, in all sorts of ways for humans, as far as I understand, are characterized by a sense of loss of your usual sense of self; a sense of becoming more continuous with the universe at large. And yet it would be very difficult to live one’s life in a permanent state of mystical experience. I would have trouble getting the train here to speak to you.

EVYou did have trouble getting the train here, Merlin. [laughter]

MSSo anyway, just to speak up for both sides. I think of them as this dynamic dance, pushing and pulling, and I like that feeling of pushing and pulling. I feel like in that dynamic place there is some balance which can lead to health.

BSI was thinking—it’s funny, actually, listening to Merlin talk, because we’ve been friends for a while and I’ve been sort of mining Merlin’s wonderful jibber-jabber for a long time, and it’s been a real inspiration for the projects that we make. And so, as an artist, I find great inspiration in these kinds of collaborations, because it’s those ideas that then we’re looking to reveal experientially. I think one thing that’s been coming up, in fact Merlin introduced me to Stephan Harding, and he goes, “When you step outside your house, you’re stepping into the body of the Earth,” you know, you’re existing inside, and suddenly you’re sort of, oh yeah, trees and like these organs, and you’re in this living body. And like, as your gut bacteria are to you, so you are to the body of the Earth. And those ideas are great, but your experience of this reality is always in your body looking out. Your skin kind of creates this boundary where it’s like, yeah I’m definitely inside, and then there’s the world outside, and so it’s like me here— But then, and this is where that flip comes in that maybe relates to the little meditation we were doing earlier, is that seen a certain way, you’re much more like a river, in that there’s this constant flow in and flow out. And that river can be seen as the relationship—it’s this exchange through breath, nutrient cycles, water, that sort of threading of everything into these relationships. And I think seeing the world that way, it sort of extends this idea of personal health to the health of the stream and the health of a forest, because you suddenly start to see that what is outside you is flowing into you, so the separation isn’t there—just purely from the idea of the molecule soup that we’re all immersed in. Yeah, something like that. [laughter]

EVYou spoke about mystical experience, and mystical experience in all traditions opens one up to mystery, you know, where the boundlessness of the individual self merges into something much greater. You know, fungi are quite mysterious, and it seems like there’s an immense amount we don’t know. And that’s very, very exciting, and maybe perhaps also unnerving, especially for the traditional scientific establishment. But in many cases the more we learn, the less that makes sense about them. And there’s so much complexity there, and in many ways fungi sit outside the current parameters of what is knowable to us. And Merlin, you’ve written about trying to enjoy the ambiguities that fungi present—that is not easy or comfortable because the space opens a lot of questions. And actually I wondered, Barney, if you could first respond to this, because I feel like that’s part of your creative process, and it’s on display upstairs, you know, stepping into mystery. Yes, you’re making the invisible visible and revealing the processes that are unfolding—photosynthesis, the way that oxygen moves, and your breath can share the breath of the forest—but there’s also a lot of mystery there, and the desire to invite people into that space of mystery.

BSYeah, I think one of the biggest mysteries is death, and part of our interest in the mycelial world and what happens after death, in fact—this could be another sort of meditation. If you imagine you were to lie down on the forest floor and you’re looking up at a tree and you take your last breath, and so in that moment you sort of drift into a slight out of body experience where time starts to accelerate. So the day-night cycle, whooo, whooo, it starts to accelerate, whoo, whoo, whoo, whoo, whoo, until like the day-night is shimmering like this [buzzing noise / blows air]—almost like when a car wheel is filmed and it stops going forward and it sort of hovers in this sort of tree-time, you sort of enter tree-time. And then you have a Trainspotting moment, where you’re sinking down, but as you sink down, you’ve got sort of mushrooms flowering through your chest, and all those branching networks that before were your cardiovascular system, nervous system, they start to beat to a different rhythm as they sort of pulsate through blooms of bacteria. A bit like a bath bomb, you kind of spread out and sink down [laughter]. But then you realize that actually death becomes life; that you’re weaving into new relationships, and that separation between the two is never like the hard edge of like lights out, actually you get eaten from the inside out—it’s like part of your bacteria flows. And I think there’s a lot of celebration in that, but there’s a big fear element to it. But in some ways maybe it’s this idea that the bath-bomb moment is this thinking that you’re a wave, that you’ve got a structure and are on the surface of things, and everyone else is a wave on the surface of things, but then as you break down and flow out, you realize that you’re part of the ocean, that kind of classic metaphor which is often a spiritual thing. I think it also relates to the way death is woven into life. I wanna make that experience, by the way, if anyone’s got a checkbook. [laughter]

MSThanks, Barney. So the word “mystery” comes from the Greek word myein, which means “closed” or “shut.” And mysteries are, in principle, those things which are unknowable; which remain concealed; which remain hidden, perhaps apart from in rare moments when one can experience them transitorily. So this sense of being hidden, of being obscured, I do think this is really relevant to fungal life, because most fungi live most of their lives immersed in whatever they happen to be eating. Lived as a mycelial network, your life is about putting your body inside your food. We tend to do it the other way round, but fungi live their lives burrowing, insinuating themselves into their food and then digesting it from the inside. And that means you’re inside whatever you happen to be eating. So from our perspective, as humans, it’s quite difficult—apart from the moments when fungi erupt into our sensory worlds, usually in the form of mushrooms—it’s quite difficult for us to see what they’re doing or to pay attention to them.

I think this is one of the reasons we know relatively little about fungal life. They were thought to be plants until the late sixties when they won their independence and became a new kingdom. [laughter] It took a while. I think one of the reasons why that was is because they remain difficult to study today. I spend time with my colleagues and the research teams that I work with, and we’re spending a lot of our time trying to make fungal life visible, so we have imaging robots which are looking at the flows within mycorrhizal networks in the lab. We get into the lab and we are looking at these videos of flows going in both directions at once, changing directions—the most complex traffic system we can imagine—and all of us are just saying, “Play it again,” and then just heads in our hands, like how are we ever going to explain and understand this? [laughter] But it’s just so mesmerizing. It’s like, “Let’s get more of these images and have a bigger imaging robot so we can see more and make more visible.” So much of our life is doing that, and how do we then make visible the life of fungi in the soil outside in the forest? And it’s just so hard to do that. Even if we had $50 million we’d have to invent a lot of technology to make imaging techniques that would work there. We are working towards this now and it’s a big part of our challenge. So even then it’s difficult to see what fungi are up to, to really understand what they are doing in biologically meaningful environments outside of the lab.

And so this sense of, you know, living obscured in the mystery, in this etymological sense—the myein, the closed, or shut, or concealed—feels very close to fungal life. That being said, I think that— With some mysteries you don’t necessarily want to try and drill through that wall into the concealed space behind. That’s not always, at least for me, the way I want to conduct myself towards mysteries. But I do think there’s a lot that we can learn from moving towards fungal life, and in that sense, maybe it’s not an actual mystery but it just presents itself as a mystery because it’s concealed in this way. But I do feel like understanding fungal life is an important part of the modern biological sciences, because so much of the living world depends on them. And our understanding of the living world is fundamentally incomplete until we start factoring them, and the many other organisms that live in the soil, into the picture. So I feel like that they maybe present as a mystery—and I think there are mysterious aspects to all of life—but maybe they’re not a true impenetrable mystery. We just haven’t quite worked out how to see far enough yet.

EVWhat do you think the role of mystery is in cultivating awe and wonder, kind of going back to the first question I raised, and kind of trying to break down some of these barriers between the scientific and artistic realms? What are your thoughts?

MSI mean, for me, the sense of wonder and curiosity and being mystified—and the mystery is what motivates me to do anything. It motivates me to live, let alone ask scientific questions or philosophical questions. So I find that those experiences are hugely important. And if I’m feeling closed or detached or exhausted or sick in some way, it’s often because I’ve forgotten about all of the wondrous things that confuse me and mystify me, and a dose of those things can help me to get back on track. So I find it medicinal to meet mystery and wonder and curiosity, and that closed-mindedness is well antidoted by that, in my case. That being said, I think mysteries draw us towards them. I like questions that are difficult to answer because they draw me into curiosity, draw me forward, they lure me forwards into inquiry, whereas if I answer the question really quickly or someone else answers the question for me, then that’s it—the question is dead. An answered question is no longer a question really. And so the unanswered questions, I find, have this very powerful allure, luring effect, and I feel without that luring, then lots of things will become quite difficult.

EVI mean, upstairs in Breathing with the Forest, it feels like you’re being lured somewhere, versus trying to answer a question. Would you say that’s true, Barney?

BSYeah. Scientists like Merlin—think of them like slugs. They leave this glittery trail behind them. And I’m kind of there like [mimics gobbling], just like yumming the glitter juice, [laughter] not necessarily asking the questions, but you know, letting somebody else do the hard work and just enjoying what comes out. I think one of the ones that really got me was—Neil deGrasse Tyson was talking about—we did a project about time and thinking about time as elastic, and we were looking at black holes. And he was talking about how stellar black holes—so they’re the ones made by stars big enough and heavy enough to leave behind a black hole when they go supernova—it’s only the ones that leave behind a black hole that are heavy enough to create all the ingredients for life. And I just love the poetry of that—this life and death, the kind of the void in relationship to all the ingredients necessary for us to be here. It’s like you couldn’t invent that! But then, they’ve measured it, and it’s there as a thing. So I think it’s those kinds of scientific stories that I find are kind of off the charts, aren’t they? You can’t make that stuff up, and so it’s everywhere, really.

EVWell, you were speaking about death as an entrypoint for life. And I want to ask you both about life forms as processes, because that’s present in both of your work. And Merlin, you’ve explored this in your writing, and obviously MLF, you brought this to the fore in a lot of your installations—the concept of life forms being processes rather than things. Instead of living beings being kind of a static fully formed matter, they are systems through which matter passes through. And in the case of fungi, the mycelial networks are “a map” of their “recent history,” as you have written, Merlin. I wonder if you could both speak to this, and the importance of revealing these processes, whether that be through science, art, writing, what have you?

MSI think this is such an important question. And it actually brought to mind a line from one of the great process thinkers of recent times, Alfred North Whitehead. A line of his just came to me just as Barney was speaking. Whitehead said that philosophy begins in wonder. And when philosophy’s job is done, the wonder should remain. And I like this idea a lot, because it feels like, to me, a good hallmark of a healthy inquiry—that at the end of it, the wonder that motivated the inquiry is at least as much as was there at the start. Whitehead was a powerful influential process thinker, and what this means is that—and there have been lots of process thinkers for a long time—and why this is an important thing to talk about is, because a lot of the way that the modern sciences invite us to understand the world, and the modern philosophies, is in terms of substances; the nature of reality is made of substances.

So, you take yourself, what you’re made of—you’re made of molecules; molecules are made of atoms, and atoms are somehow little billiard balls of stuff. Matter is stuff, a substance that is fixed and unchanging somehow, until it is changed. And that’s all very well. But the problem is that the nature of reality doesn’t seem to be very much like that really, when you boil it down. An atom is more like energy bound within fields—it’s much more like a process than a thing. This matters, because if you’re a “thing” person—and I think we’re all a bit “thing” people and a bit “process” people; I think it’s an ancient dialectic—but from a “thing” perspective, what you have to explain is why things change, because left to everything’s own devices, it will just stay the same, because it’s a thing, it’s a substance, it’s unchanging. So you have to explain why things change, because things won’t change unless they’re changed. Whereas if you’re a “process” person, you boil it all down and you have unending flux, continual unending flux, then your question is why does anything ever remain stable? How do we account for stability in the universe? And that’s a very different question to how do we account for change in the universe.

I think both are important questions and both perspectives can lead us to very healthy places, and I think it comes down to ancient dialectic, because we find this in many theological schemas from around the world. One of my favorites is that of Shiva—the creator and the destroyer, the deity of powerful flux—and Vishnu, the preserver; this was within Hindu philosophies and theologies. And you need the creation, the destruction, to generate novelty and possibility, but without any preservation there could be no stability, no form, and none of the things that we see as things. So I think this dance between process and substance is very ancient. I feel like the substance view has received perhaps more than its fair share of emphasis within the modern sciences, which is why the process view can lead us back into very important questions.

BSI totally forgot what the question was. [laughter] Can you give me a reminder? I was lost in the—

EVThe importance of emphasizing—revealing processes versus things, I guess is the simple way to answer that.

BSOkay. We did this project a while ago called In the Eyes of the Animal, and so that was based in Grizedale Forest—there’s a sculpture park up there, and we did a Lidar scan of a section of the forest. And then from that we worked with a number of different scientists to explore what would the world look like through the eyes of a midge, a dragonfly, a frog, and an owl. And in that process of sort of trying to understand how another organism might see the world, you very quickly run up against—in fact, there’s a famous essay by Thomas Nagel saying, “What Is It Like to Be a Bat.” And it’s impossible to really know for sure, but I think science can tell us a certain amount, and that can give us a bit of information about how we might flavor your human senses through the lens of dragonflies, for example. They’ve done some tests where they’ve figured out, if human perception is sort of between twenty-five—you know, if you’re watching a film at twenty-five frames a second, it’s smooth. So you could say, if you’re talking film frames rates, that’s the human frame rate of reality. Whereas for a dragonfly, it sees the world at three hundred frames a second. That would be a very boring film, it would be like grandad’s slideshow at Christmas—the lamppost slideshow.

When you start to step out of the human-flavored reality and explore these other spectrums, you realize that everything is kind of existing in relationship to everything else in its own sensory kind of dialogue. A plant has got certain color spectrums within it that are only available to the pollinator, and although we get a reflection of that beauty through the scent, it’s actually a dialogue that’s not designed for the human being. It’s a dialogue between a moth, or a bat, and a certain flower, and some of those relationships have sort of shimmered in relationship over deep time, you know—really entangled. So although we can appreciate, I guess, the beauty of the world through the human lens, I think when we start to shift and see it through the more-than-human lens, then it does create an interesting [perspective] … those experiences and stories can stay with you and maybe flavor the way you see the world afterwards.

EVWe’ve been talking around this, I guess, the entire conversation, but I’d love to ask it more directly to both of you. How might fungi help us break through the traditional Western philosophical frameworks? You spoke about the Hindu philosophical framework in your last response, Merlin, and I think it’s really important that we look beyond the Western philosophical framework at this time, whether that be to ancient cultures, like the Hindu culture, but also traditional Indigenous cultures that have held very different worldviews for millenia, more than we have. How can we step outside of ourselves and challenge these models, and how can fungi be a gateway to that?

MSThis is a very profound question. I’ll try to be brief. So I think we can learn many things from fungi that can help us in this quest. And some of those things might be, as we’ve already discussed, the fundamentally intermingled nature of the living world and the universe. And if fungi can lead us to that place, then I think we are already stepping outside a number of, perhaps, constraining philosophical systems that we inherit; that I’ve inherited as a resident of a North Atlantic country here. Then, thinking fungally, you would think, perhaps, about cycles much more, because from a fungal perspective there’s no such thing as a waste. Everything created by it, every chemical or substance or product of any other life form, is an opportunity for growth. I think you enter a much more cyclical point of view from thinking with fungi through the various ways that they live. And I think that that cyclical point of view is something that you find enacted in many different traditions around the world. I think you would also come to a place of understanding that humans aren’t the only way that intelligence manifests in the world, and I think that’s very important for overcoming a lot of our species’ narcissism and exceptionalism. I think that’s something that you’d find, again, in many different parts of the world, in many different traditions. I think fungi can take us to that place, because the ways they live make it clear that you don’t need a brain to solve complex problems. I think you could get to some very interesting places by thinking about process, as we’ve discussed. The mycelial network is a body without a body plan. There’s no sense in which this network could ever be fully grown, like we could. And so you might end up in a more processual space, which, again, might be something you’d find more present in traditional systems around the world.

And then, back to this mystery point—I think fungi teaches us about the power of what lies beneath, what lies hidden from us. And a lot of what we might call Western scientific and philosophical traditions come from the Enlightenment, and this was very much about shining a light on things, revealing things. This metaphor of light and seeing is very powerful in this whole diaspora of thinking. For me, fungi, in reminding us of the power of what lies hidden, of what lies beneath, what we can’t see—all of the subvisible realms, all of these organisms that create the atmosphere in which we live, that have shaped everything we know about the living world—I think fungi take me to that place as well. I think that sense, that intuition that there are some things that we can’t know by shining light on them; there are things that just are always going to be that mystery place: the myein, the closed, the shut, the hidden—I think fungi can take us to that place, too, and I think that’s something you’d find in many of these traditions around the world.

BSAs you were talking, it was making me think about this idea of the limits of our perception. And so, you know, I’ve got a great relationship with my dad, and I’ve got some dear friends, and my dog, so the “living organisms” that I encounter on a daily basis—I’m woven into relationship with them. But obviously we live in a strange time where you can reach for a can of tuna, but then that extends through a supermarket into a fishing boat that’s reaching into an experience for that tuna that is so detached from me in the shining light of the supermarket. I often think about, you know, in a culture that’s global, where that mycelial web of how your actions extend into relationships that you’re so distanced from. I think it’s interesting to think about—we’re thinking with the work that we’re making—about how you can bring that geography of the tuna, the magnificence of that organism, into direct contact with you as you’re sort of reaching for the tuna. There’s the ability through the technology to maybe peer past the smokescreen of advertising to reestablish those relationships. Because one thing for sure is that, you know, if you were to experience certain things like deforesting through eating chocolate spread—it’s a horrific idea. You’re like, “What?!” So, I think there’s, in some ways, this idea of direct relationship to, you know, this expanded planet is something that maybe inspired me through what you were saying.

EVMerlin, you spoke about intelligence and, you know, for a long time now human intelligence has been the yardstick by which we gauge a level of what is intelligent or not not. And I feel very strongly that part of what needs to shift through this entanglement that has been again revealed to us through the ecological disaster that’s unfolding, pushes us to reconsider that again—that human beings aren’t necessarily the most intelligent forms of life out there. Fungal networks are incredibly intelligent. Slime molds. There are many forms of intelligence out there, but it seems like the fungal world, the mycelial world, has captivated people in a way that other forms haven’t, you know? From Suzanne Simard’s paper in the late nineties to now, the wood-wide web has become a term many people know and understand and are captivated by, and it seems like there’s a doorway there, a doorway perhaps that’s growing as we become more and more aware that there are other forms of intelligence out there; to reconsider ourselves in a very very different way. So I wonder if you could speak to that.

MSAs you say, the traditional definitions of intelligence within the modern sciences come from a version of cognitive science which placed the human at the center of the inquiry. And, of course, it would start there, that makes sense. So many of the traditional definitions or measures of intelligence, like being able to recognize oneself in a mirror, being able to solve certain kinds of problems—they were shaped around our understanding of our intelligence, which, again, makes sense if you’re assessing human-like intelligence. But the problem is when that becomes the ultimate definition of intelligence then we do, I think, some bad manners, and we disservice the many other organisms that we share the planet with. Because by trying to fit them into our categories, when they fail to fit into our categories that we have made for them to fit into, we dismiss them somehow as being less intelligent. So this is the problem.

But thankfully these definitions of intelligence have started to change in recent years, and this is coming from a number of different fronts, from aspects of philosophical inquiry, from computing and artificial intelligence, through various areas in the biological sciences. And it now becomes clear, I mean, you can define intelligence however you like, right? But the ways that I find this is happening in generative ways is that, now, intelligence, you might think about it not as something an organism has or doesn’t have—i.e., is this intelligent or not?—but rather as different sets of behaviors, like the ability to solve problems, different kinds of problem; the ability to choose between different courses of action; the ability to adapt to a changing circumstance, to changing environments. And when you look at it like this, it becomes clear that all organisms, to some degree, are intelligent, because the challenges of living present one with problems that you have to solve, and organisms have evolved to solve different kinds of problem.

One of the reasons why organisms are different from each other is because they have evolved to solve different kinds of problems. So the problems that we can solve and we’ve evolved to solve are different kinds of problem than those that befuddle a plant, and the plant’s evolved to solve those different kinds of problems. So that I find quite helpful because once we make intelligence less of a special thing, it actually becomes just a very fundamental part of existing, and we also destabilize one of the things that we think of as making us so special. But I just think it makes it more fun—the living world becomes a more exciting place to live, because it’s a place where we’re all living with other organisms all improvising through time, improvising within a set of constraints that we inherit through the quirks of evolution and the nature of bodies and senses, but all facing possibilities—and E.coli bacterium faces possibilities—and within that possibility space there is opportunity for choice. It can use its flagellum to propel itself in a certain way, or it can stop, and it has other degrees of freedom. So improvisation I think of as just the tension between one’s constraints, one’s possibilities, and the degrees of freedom one has to act in that space. And I think all organisms are, in their way, improvising through time and lineages; are improvising through evolutionary time. So this is something that I think is a— Oh rats! I’ve forgotten the questions. I was improvising. [laughter] I forgot the question.

EVI think at this point it doesn’t matter. Intelligence—

MSSo the possibility space there was getting the better of me and I forgot the constraint of the question. [laughter] But the point is that the deepened and expanded understandings of intelligence change the way we think both about ourselves and the ways we relate to the world, and I think it’s an important thing to have destabilized and made more porous and flexible.

BSI was thinking about a Richard Powers quote—I’ll probably get it slightly wrong, but he talks about this is a world of trees where humans have just arrived. So I think there is a fundamental shift in like, do you feel that you grow out of this Earth, part of this unfolding process of deep time where you’re inseparable from the relationships? Everything about your senses has coevolved in relationship to the living world. So you’re not this thing that’s separate, observing it, you’re part of that fruit. Alan Watts—I love Alan Watts—he’s got a real peach where he talks about this idea of apples on an apple tree. And so the idea is being an apple on a tree and not realizing that the tree is alive, that you’re paying attention to the other apples, they’re coming and going, they fall off, they’re living and dying, but you don’t recognize that the tree is alive. And that’s like us not understanding that the Earth is a living being, and that we grow out of it. And I think if you see the world that way, how could you ever not imagine that there’s intelligence embedded into the tree, into the whole thing, into the whole living being. So I think that’s the way that makes sense, to me anyway.

EVSo I want to end the conversation by talking about survival and adaptability. Merlin, you write that “fungi are veteran survivors of ecological disruption,” and they have a remarkable ability to adapt to fragmenting environments and landscapes experiencing catastrophic change. And not only do they survive through such conditions, they often flourish, in part because “they are inventive, flexible and collaborative.” How could a deepening of a relationship, a partnership, with the fungal community—from us towards them—help us adapt to the ecological crisis we are now in? And what can we learn from them that’s really so relevant right now?

MSLichens—I’ll talk a bit about lichens, because I think this helps to illuminate your question. Lichens are symbiotic organisms. They’re made up of fungi and algae and bacteria and any number of different kinds of combination. You will have seen them around. They encrust graveyards, they live on roofs, fence posts, on rocks, on seashores. They live on some of the most inhospitable places on the planet. When a volcano throws up a new island in the Pacific Ocean, a newly formed rock, the first things to live on this rock are lichens that arrive either traveling by sea or by birds. And these lichens can, because of their togetherness, because together they make a kind of planet—the fungus can do things, the algae can eat light and photosynthesis, the fungus can eat the rock, the bacteria do all sorts of other important things—but because they’re together, they can live in this place that none of them could live in alone. And in fact, they would look completely different alone. They wouldn’t make this elaborate, colorful form producing these widely strange chemicals that only exist in this lichen lineage—sunscreens, antimicrobials, crazy things are produced by lichens out of their togetherness. So together they could do something they couldn’t do alone, and this is really a kind of maxim in the story of life. In so many moments in the story of life, organisms come together in a way that creates new possibilities; that enlarges that possibility space. And a lot of these relationships, these symbiotic relationships, have gone on to change the planet and the conditions for life.

Many of these relationships have formed at times of crisis. Crisis is a crucible for new relationships. And so, in thinking about the ways that fungi have persisted through these five great extinction events—of course not all fungi persisted through that time, lots of fungi would have been eradicated in these moments of cataclysmic change, but many could survive somehow. And many of the ways that they survived was in striking up new relationships. So when we’re thinking about this time of crisis that we find ourselves in, I think one of the things we might learn from fungi—of course we’d also be learning it from the rest of the living world, because fungi aren’t the only organisms to do this—is that to adapt and to move through this mess, we will need to form new types of relationship with non-human, more-than-human organisms, but also with humans, and across human ages, cultures, different points of view, disciplines—all of this.

I think so much of the challenge of our times is about forming new relationships and thinking as lichens. So think about lichens as a principle, rather than just an organism. Think of lichens as showing us something fundamental about how life proceeds, and lichen-ize ourselves in new ways or maybe in old ways that we’ve forgotten about. So this is one way that I understand the ways that fungi have persisted to inform the ways we might think about moving forward. Our relationships with fungi might look like remembering our long history with fungi in fermentation, making alcohol and foodstuffs, recruiting them for metabolic purposes. We might work with them to develop the field of mycoremediation; to try and think of the waste products that we generate as opportunities for fungi to do their metabolic wizardry. We might think about all the ways we’ve depended on fungi for drugs in the past; for chemicals that changed the way our bodies and our minds work. We might think about moving forwards into a more profound exploration of the chemical ingenuity of fungi and how they might produce compounds that we need, or those organisms that we depend on might need. We might think about how, when we grow plants, we are always growing fungal relationships because all plants depend on fungi. So how can we become more mycologically literate in our forestry, in our agriculture? We might think about how we build things. Are there ways that we can change the way we make materials? Can we work with fungi to build things, myco-fabricate things? Can we use the powers of those materials to disrupt polluting industries?

So these are some of the ways that we might partner with fungi moving forwards, but each one of them has a longer route into tradition and going back into the past. So I think, each one of them, if we see them as part of an ongoing inquiry that humans around the world have already started making and that we just need to grow them forwards like a fungal cell would grow, then I think it would be a more exciting story than if we pretend that we are just inventing these new methods. We are deepening them and expanding them and exploring them, but many of them have very, very long roots and we can trust those.

BSI was thinking about—so stories flavor our reality. They’re like the operating system through which we interpret the world. And when the dominant narrative is one of separation, then there’s a certain way of being that sort of allows you to act in a certain way where you look after number one and your family and those dearest to you. And I think the stories that Merlin’s talking about here are stories of symbiosis and interexistence and interbeing. And so I’m really interested in how you address this sort of myth of separation through an experience of interbeing, especially when a lot of our experiences as humans put us, like we were saying before, inside our skin, looking out. I think you could argue that it feels like I’m separate more than part of the greater whole. So I think, you know, what’s the experience of being mycelium? Given that people can drive or captain these huge oil tankers and they can get round corners without hitting stuff, how far can you expand the boundary of your being? You know, can you embody a forest? One of the things we found really interesting—actually two things: one is that when you smell the smell of a pine forest in an office, you think of toilet cleaner; but when you’re in virtual reality seeing a forest and you smell exactly the same thing, you’re like, “I’m so in the forest here.” It just puts you there. There’s these tricks where you can—for example, you can be embodying a mycelium web in the forest and a branch lands that you want to consume. And so if you imagine yourself as sort of expanded—maybe the forest is sitting on your chest like the surface of your skin, and so all you need to do is have a visual cue with a sensation of maybe a little gust of wind on your leg hair, maybe that’s where it happens, with a sonic cue as well. But then you could also just be like, well I’m going to go over there and there’s activity happening there. So this idea of sort of extending your body and expanding perception—I think that’s our sweet spot, that’s what we’re engaged in. And it’s these wonderful stories that, when translated to experiences, could flavor the way you act and the way you behave in the world.

EVThank you, Barney, thank you, Merlin, for this lovely conversation. Real privilege to share a space with you.