Photo by Andrea Pellerani

Learning to Listen to Plants

Emmanuel Vaughan-Lee is an author, Emmy- and Peabody Award–nominated filmmaker, and a Sufi teacher. He has directed more than twenty documentary films, including Taste of the Land, The Last Ice Age, Aloha Āina, The Nightingale’s Song, Earthrise, Sanctuaries of Silence, and Elemental, among others. His films have been screened at New York Film Festival, Tribeca Film Festival, SXSW, and Hot Docs, exhibited at the Smithsonian Museum and London’s Barbican, and featured on PBS POV, National Geographic, The New Yorker, and The New York Times Op-Docs. His new book, Remembering Earth: A Spiritual Ecology, is forthcoming from Shambhala in summer 2026. He is the founder, podcast host, and executive editor of Emergence Magazine.

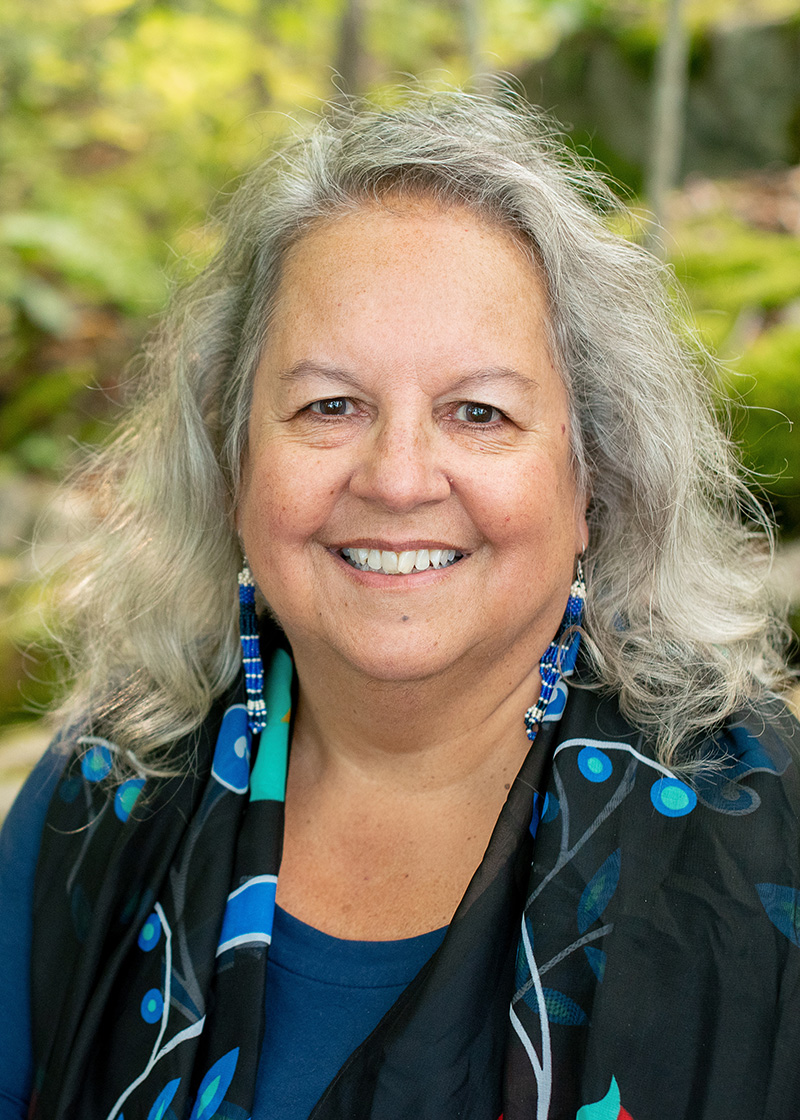

Monica Gagliano is a research scientist renowned for her pioneering work in plant communication, cognition, and subjectivity. Recognized as one of Biohabitats’ twenty-four most “Inspiring Women of Ecology,” alongside Jane Goodall and Rachel Carson, her research challenges conventional boundaries of intelligence and inspires new ways of relating to the natural world. Monica’s contributions include numerous influential scientific papers and the books Thus Spoke the Plant; and The Mind of Plants, co-edited by John C. Ryan and Patrícia Vieira. She is a research associate professor in evolutionary ecology in Australia and a free-roaming explorer bridging Western and Indigenous science to develop innovative approaches to planetary challenges.

Working with knowledge imparted by plants through dreams, visions, and sensations, scientist Monica Gagliano offers a real-world example of what reimagining scientific knowledge can look like. In this conversation, she speaks about how her groundbreaking research on plant communication and cognition has evolved as she has nurtured a relationship of reciprocity and trust with the plants she studies, modeling how we can radically bridge the rigor of Western scientific methodology with the deeply human and spiritual act of listening to plants.

Transcript

Emmanuel Vaughan-LeeMonica, welcome to the show. Thank you so much for joining me today.

Monica GaglianoThank you, Emmanuel, for having me.

EVLSo I just finished your book, Thus Spoke the Plant, which details how your work in plant cognitive ecology is directly shaped by knowledge imparted through your interactions and dialogues with plants—that they communicate to you in dreams and visions and conversations, as well as via more traditional forms of scientific experiments. So I wonder, to begin our conversation, if you can offer an introduction to how these experiences shape your work?

MGI feel that most people actually have these experiences. I just happen to be one that is having these experiences and is also a scientist, and so, again, translate those experiences into a language—one of Western science—that makes sense to people who do not think they have these experiences, if it makes sense. So, connecting with the more-than-human world—and plants, obviously, are part of that more-than-human—it’s a very basic human capacity. Like if you’re human, you qualify. And this connectedness is sometimes expressed in, as you mentioned, you might have a dream or you might have a sensation or a physical sensation or an emotional response to something that, if you pay attention, you might recognize is coming from your garden, for example, or from a forest while you are just going for a stroll.

And my work emerges simply from these very common experiences, as I said, that are then translated into a more structured world, which is that of Western science. And, I guess if you go down that rabbit hole deep enough, you find out that these “others” are quite willing to collaborate, not just to be heard, but literally to have a say that can together create something different, something new. So I’m not a plant biologist, for example. I was an animal ecologist and I didn’t know anything about plants. And actually, to be honest, I was pretty plant blind, which means they’re in the background, they are the background, and I don’t really know their names, I don’t really know what they do; and they’re pretty, especially when they flower, but that’s about it, which is what most plant blind people would perceive plants to be.

And, so they—the plants—decided it was time for me to stop being blind and make their presence really felt in my life and in my work. But because I wasn’t coming there as a trained scientist, I approached them differently. And so, in a way, I wasn’t afraid to ask questions that we normally ask of animals, questions like: How do they learn? Do they learn? Do they remember? How long do they remember for? What do they remember, or how do they communicate? What do they use for communication? Are they listening? Are they smelling? Are they watching? What are they doing? So all of these questions that, if you think of any animal, we would be like, oh yeah, of course. We’ve been asking those questions for a long time of animals. Then you apply them to a different kingdom, which normally is underestimated for this capacity, and suddenly those questions seem so controversial. But actually they’re just questions that we haven’t asked.

EVLI mean, you said they’re controversial, and if you were asking those questions in the context of animals, it might be different. But you are kind of pushing boundaries within the scientific establishment by relating to plants like that or considering them to have intelligence in a way that most established scientific schools would say, no, that’s not allowed. But, the irony here is that although this is cutting edge, what you’re doing, it’s actually really not cutting edge at all, because human beings have been working with and learning from plants since time immemorial, just only recently in the Western modern world have we stopped doing so.

MGThat’s right. In a way, this is like the quintessential form of the colonized mind, you know? It is only for the last few hundred years that we have decided, literally, that we need to catalog and observe in a detached way and describe it systematically, and all of that, which then becomes the foundation of botany and much of Western science. The detachment from “the other” is a fundamental element for this new science, which now we consider “science,” or “modern science” as we call it sometimes. But you’re totally right. I mean, all of my work, in fact, is inspired by Indigenous spaces where this kind of knowing is not even discussed because it’s so obvious, so everyday, in a way so simple, that you would think like, why would we even talk about this? It is like, Of course, I’m talking to those trees or the land or whatever, the river. If I need to work with them or if I need to pass through that, if I need to walk up that mountain, I’m going to ask permission before I do. And, of course, the mountain is going to grant it or not, and I have to listen because otherwise things will happen.

And so this kind of posture has been our way of moving in the world, as a species, for the majority of our time. It’s been that posture. And it’s only more recently, as I said, a few hundred years of like, nope, we are not doing it that way anymore. And the amazing thing about this Western or Eurocentric approach is that it has managed to spread this idea as a dominant paradigm across the world. And now we call it colonialism, because, literally, it’s trying to suppress other versions of reality to confirm its dominant version. But it’s just one version of reality, as it’s always been. And so I think it’s important for us as the practitioners who are within that system of, in this case, Western science—but it could be just a standard, as well as Western thought—I think it’s our responsibility to question it all the time. And to ask, does it actually stand? Is this the only way to see? Is this the only way to think about things? Because nothing changes if we don’t question.

EVLRight. Well, you perform experiments within what you could call a traditional Western scientific approach. But some of these experiments, and you described this in the book, have been instructed to you by the plants themselves—how to, I guess, perform an experiment that would prove something that the plant already knows.

MGThat’s right.

EVLTell me about this.

MGI want to preamble that when this was happening for me, I really thought I was going crazy, too. So I’m aware of how crazy this sounds. And yet, this is what has been happening, and now I’ve been approaching all of my work like this. But I guess you’re referring to one particular set of experiments with peas. I was in the Amazon working with a big tree and following some very scientific, by the way, methodology from the Indigenous approaches there with plants. And I didn’t go there thinking like, now I’m going to go and the plants are going to give me some experimental instructions to do my science. Nothing at all. It was more like a personal exploration. I just wanted to learn more about this thing that they talk about: that we can connect with these others that are so alien to us because they’re so different—at least on the surface.

So that was my approach. And then, almost out of the blue—but then if you know the practice, you realize it wasn’t out of the blue at all, that’s how they do it. But, to me, it felt like out of the blue. I found myself one morning keeping my diary, which I always keep every day when I’m traveling, especially when I’m doing these kinds of experiments or practices. And I felt like someone was dictating and making me draw things that, at first, I didn’t know: What is this? What am I doing? And then the more it appeared and the more details that appeared—they were like literally the size of the pipes that I needed to use, and “do it this way, not that way.” And “by the way, if you ask this question, you need to use this plant, not that plant.” And I was like, what’s going on? And then, of course, when I had it all in front of me, I was just staring at it thinking, this is an experiment. They just gave me instructions on how to do my job.

So, the real madness happened not so much in the Amazon, but when I got back to Australia and I went to the lab and I set it up according to what was instructed. And I ran this experiment that for two weeks was piloting, basically, so testing and checking things were working. And after two weeks, I came to the conclusion: Okay, I’m just being an idiot. This is not working. What was I thinking, that a plant gave me instructions on how to do my work?

And there was that one moment, which I think all of us have these moments in our lives, when a little split second changes everything. And we could have gone one way and instead we got kind of pushed some other way. And that was one of those moments, because I was about to dismantle everything, thinking like, what was I thinking, really? And probably I am losing my mind. The experiment was running in complete darkness. The only little lights that were there were like little blue lights that were used for the experiment itself. And so I was in complete darkness in this cold room and these blue little lights in the room and that’s it. And I was about to just switch everything off, dismantle everything, and end the experiment. It didn’t work. What an idiot. And instead, something stopped me, and there was this kind of internal voice that invited me to slow down, wait, and look again. And so I did, and I don’t know what happened, because I cannot really explain it even to myself, but I know that I suddenly saw something right there that I couldn’t see until that moment about my plants and what the plants were doing. And they had been doing precisely what I was kind of testing and hoping they would do for two weeks. It was just that my own perception and my own preconceived ideas through training and through expectations didn’t even allow me to see what was actually happening right in front of my eyes.

And so, I don’t know what that moment—I call it the intervention—was, but definitely something happened. In that moment, I learned two things—and probably much more, but those two that I am aware of—very clearly: One, I don’t know anything about what I’m doing, and so I am literally learning as the experiment, in this case, is happening. So I’m not the one that knows what’s going on. I’m the one that is participating in what’s going on. So that was the total breakdown of the famous “objective observer.” It’s like, I am totally part of this experiment. I’ve been kind of roped in, and without me this is not happening. But not just because I have the physical hands that can make it happen, but also because I am the experiment with the plants.

And the other thing that I learned, which was really important for my little self—because this is not an easy path as an academic, as a woman in academia, in science. It can be very lonely. And there is still plenty of, I would say, bullying and aggressive behavior towards something that is different, as we often do. We don’t like things that are different. We want them, but then we don’t like them when they arrive. And, in that moment, I realized it really gave me this sense of like, oh wow, my colleagues, those ones that attack me and tell me that what I’m doing I shouldn’t be doing—“What is this stuff?” you know, all of those behaviors which are a fear of the new—I was one of them just five seconds ago. They cannot see, just as I couldn’t see five seconds ago. And now just because I’ve been given the privilege of seeing something else, suddenly I get it. And so it gave me this feeling of like, oh wow, they’re attacking me because literally they cannot see what I’m pointing at. And so I’m pointing, they see nothing. And they tell me like, “What’s wrong with you?” while I’m pointing and I see something, and it’s like, what do you mean, don’t you see? And no, the answer is no, I don’t see. That’s why I feel threatened. Because you’re pointing at something that I’m supposed to know, but I don’t. I’m supposed to see, and I don’t see.

I think, then, we find a little bit of consolation when we look at the history of science and how this has been the case for every single piece of new science that has emerged, including Darwin himself. He was so paranoid about his work coming out, and he was very cautious. And, of course, he got a lot of backlash for what he said. Because at the time it was like, well, can you prove it? And he was like, no, I can’t even prove it, it’s a theory. And it took a long time for that theory—a beautiful idea—to then become something that’s like, Oh, actually, yep, now we can see. We have the fossil records and we have this and that, and we can put it together and, yeah, it makes sense. But this is the case with much of science. So, I kind of feel like, okay, this is how it goes. And so maybe I am doing something that is really contributing, and if that’s the case, it’s all good. It’s worth it.

EVLIt seems from reading about your work that some of your experiments, and you just described this, they often reveal more about the human than the plant. They underscore our embedded conditioning around intelligence, our relationship to the more-than-human, the limits of our own imaginations, really. And I love that you describe plants as teachers, and perhaps that is partly why they help reveal ourselves to ourselves. And you know, they’ve always done this, really—being teachers and revealing ourselves to ourselves—when you look at Traditional Ecological Knowledge.

MGAbsolutely.

EVLBut as we said earlier, this has shifted. And you suggest that in order to move forward in our relationship with plants, we need to surrender a lot of our biases about the world. Beyond just science and how Western modern science practices traditional forms of experiments or whether things are intelligent or not, there are larger biases we have to surrender. Talk to me about this.

MGWell, yeah. Where to start? The first one, I guess—and again, it seems so trivial to even say it, because we actually already know all of this, so I’m not saying anything new. And I think most of the things that we speak of have already been said so many times in general, and we just need to say them again and again until maybe we get it. The book Thus Spoke the Plant came out in 2018. I have changed quite a bit since then.

EVLI can imagine.

MGI’m actually writing, already, another book. It took me almost ten years, but we are getting there. And I realized that I’m writing very differently because I had to accept some of those biases in me and then let them go. And one big one that I find is, at the moment, driving my writing is precisely this idea of: I don’t know what I’m doing. I don’t know what’s happening. But this “don’t know”—it’s not like, oh, I’m not intelligent enough, I’m not smart enough, I didn’t read enough, I’m not educated enough, or whatever “enough.” I’m not good enough. It’s not that. I feel it’s the most powerful place to be, to get a chance to know. And “to know,” in the sense of the Latin root, is actually connected to taste. So to know something means to taste something. So if you want to know life, you need to have a taste for it. Literally, you have to eat it, which we do every day, especially with plants. So, in a way, if we could taste our food, literally—so the plants that enter us every day and then make us every day, physically, like the material building blocks of our bodies—if we could taste that with the awareness of like, Wow, I’m being remade all the time by these others, and they look so alien, and yet they can create something that is so familiar, my body, I think our knowing would change in its form and it would become something much more almost contemplative. It wouldn’t be so fixed on facts and what is and isn’t—this black-and-white approach. It would realize like, oh wow, I’m just a continuum, I’m an analog, instead of this digital form of life, which of course right now is particularly strong as a view.

So that would be the bias that I think would be the most useful to acknowledge: that we don’t know anything, but we are here to taste life so we can know life. And that’s the job. And the moment you think you know, then you have to dismantle it again so that more life can enter you, more life can be tasted and known. So it’s a constant undoing.

EVLWell, that’s a very mystical approach to working with plants versus the traditional, you know, not-knowing mind or the understanding of mystery and the unknown as a container that doesn’t overwhelm, but actually invites.

MGThat’s right. That’s the thing—it’s like, for some people, I think it sounds too, I don’t know, too hippie, too airy-fairy, too New Age, even. But I want to caution people that might think that. It’s actually from this space that you can apply whatever tools you have. And Western science as a methodology offers particular tools that can be applied when it’s the right time. And so the same is valid and is true for other kinds of sciences. Like Indigenous sciences have very specific tools that can be applied at a particular time for specific things. So it would be like, well, if you had to do surgery, do you need a hammer or a scalpel? The good doctor knows what to use when. Sometimes you do need a hammer. Sometimes it’s only a very fine job with a scalpel. And so I feel like having this space of openness, which this unknowing allows, you then have the freedom to choose which tool you’re going to apply instead of feeling that you can only and always apply the hammer, or only and always apply the scalpel. Not true. We have so many tools. Why shouldn’t we play with all of what we have?

EVLRight. Well, maybe to speak about something pretty specific: you describe an encounter you had with a Socoba tree where you were taught that this tree can be used to help treat conditions of the human circulatory system. And on the back of this, we would normally ask, how can we use that tree as a resource to heal ourselves? That would be the question we’re asking, or the investigation. But after learning this directly from the Socoba, your questions were: How can these plants hold such knowledge about the functioning and healing of the human body, and why do they hold it? So I wonder if you could talk a bit about where these two questions have led you.

MGI still don’t have the answers to those questions, and I like that, because it allows me always to ask them. And I have asked them again and again. More recently, I did a big project, a collaboration, with a forest in the Dolomites in the north of Italy. And in that case, it was the same. I approached, exactly with those questions of: I know you know, and I know you know more than I do, so first of all, am I allowed to be here and work with you—you forest, you trees? And the second question was, teach me, show me, you know? Instead of like, I know what I want to do, it was more like, what is it that you want to show, because I know that you know. And what I got back at the time, at the beginning of the project, was a very clear message, which made no sense whatsoever—because it often sounds like a riddle, and then it makes sense later. And the forest was like, you’re very welcome to work with us. We are happy that you are here, but be aware that the story to be told is not what you think.

And I thought I was already going open enough not to think anything. But of course, we always have agendas. We wanted to do an experiment on the perception of sound, different sounds, natural sounds in the forest, by the forest, and as we started that work, it became very clear that that wasn’t working at all. And so we’re like, oh God, what’s happening? We had built this infrastructure. I was working with a few physicists and engineers, and they built this amazing infrastructure that allowed us to monitor the bioelectricity, so the biological activity as a summary in the form of electrical activity, of the individual trees as well as their connections. So we were looking at the tree as an individual as well as the forest, basically, like a collection of trees.

And it just happened that while we were trialing all of our own questions—would they recognize the sound of this or that? and how would they share that information?—and that wasn’t working, it just happened. And this is, again, a very common event in science: something that wasn’t planned happened, and then it becomes the main thing that you’re doing. We had a solar eclipse passing on the site, and because we had all the infrastructure working, the infrastructure just kept recording and pushing out data of what was happening to the individual trees, and then the trees as a collective. And so, you know, we had plenty of data before—the baseline. We had the moment of the eclipse, and then we had time after the eclipse. And what we found is that, very briefly, basically as the eclipse approaches, all the trees in that little group changed significantly their bioelectrical behavior. And we could detect it. There was a big spike. Something happened that was huge. And there was nothing—we were monitoring temperature, light, and all the usual stuff, and it was like there was nothing, except that that change started with the older trees and then it got transferred to all the other trees. And by the time the solar eclipse arrived, all of the trees—which before that were doing their own individual thing—were all synchronized. So their signatures were all the same. So before the eclipse, you had the individual trees. During the eclipse, the trees are all synchronized like a flock of birds or a school of fish moving together, in this case bioelectrically. And then when the eclipse passes, they all return to doing their own individual thing. So this gave us the opportunity to see the individual trees as well as what we call “the forest,” the collective, and how different components of that collective have different roles, they have different memories. Solar eclipses are something that, for humans, seem to be these random events or rare events. They’re actually not random and not that rare in the sense that they have their own cycles. And in this case, an eclipse like that would return every eighteen years in the same place, more or less, which means that if you’re a tree that is older than eighteen years, you’ve seen that before. And we suggested in the paper that the older trees start [that bioelectrical change] first because they’ve had that experience several times before and they recognize that something is coming, and they tell the younger trees, who have not had that experience before, to prepare. So then they all synchronize, and once the thing is passed, then everyone can return to doing their own business.

And when we finished the study, that became the core of the work that we were doing. And I remember those words that were echoing in my mind at the beginning of the experiment when the forest was like, yeah, yeah, but the story to be told is not what you think. It’s almost like they already knew what they wanted to share and they already knew what was coming and somehow we were just there at the perfect time, and so they were able to show us. This collective behavior, the long-term memory, collective behavior in a forest in response to something that is relating our planet with the cosmos—because we are talking about Moon, Sun, and Earth interacting—this is a big pattern that I think for our minds is kind of a bit too big to hold.

EVLWow. Wow. You know, there are two big questions that arise after encountering your work. One is, how does a plant speak? And the second is, how can we hear its voice? And you write, “The voice of the vegetal other is revealed in a place of reciprocity,” which I really resonated with because of this notion that we may only hear the voices of plants, that their language may only be revealed to us, once we are in right relationship with them. Which you kind of just described: how being in the space of openness in your own self before you go into this forest in the Dolomites allowed something to be communicated to you before it happened. So I’m interested to hear your thoughts about how we can move towards this space of reciprocity with plants.

MGWell, I guess the first thing would be to, again, drop another expectation, which is, at least in my experience, that communication with plants isn’t like you suddenly have this booming voice telling you things. So, just in case people are expecting that, I never had that myself. Maybe some others do, but it’s more about—

EVLIt wasn’t a burning bush moment.

MGNo, no. [laughs] But in my experience, that communication comes very clearly, as I said, as a sensation, and sometimes as a well-formed thought that I know is not mine, because some of the content I would have no possibility to know about. As you mentioned with Socoba before, I’m not a medical doctor. I had no idea. I didn’t even know what tree that was when I was working with it. And it took me ten years to— When I came back home after that experience, I looked for information on that tree and there was nothing. So I just thought, okay, I just have to accept that that’s what happened. Then when I went back to start writing the book, and I looked again for the information on this tree, then suddenly I started coming across more recent work that was on this tree in particular. And they were just showing, scientifically, how this tree is good for blood conditions—it cleans the blood. And I was like, oh, okay. But it took ten years. So, again, dropping the expectations. And if this happens over and over again, you start, also, to build the trust that this other actually knows what it’s saying. It knows what it’s sharing with you. And it feels to me they’re sharing the information that they know you, specifically, can hold and use for whatever it is that you’re doing.

So I think this building of trust is part of, also, that reciprocity that we are talking about. Because if you imagine human relationships, reciprocity is built on trust: that you will not take advantage of me; that I’m giving you everything I can, and you wouldn’t just take it and run. But it would be more like, oh, thank you and I’ll do the same. And so that trust builds, like in any relationship, over time. And it requires that we spend time with, literally, like in this case, even just in a garden or spending time out in nature, whatever “nature” is. And I think that is the foundation of the reciprocity. Then the reciprocity is not something that you do, it’s something that just emerges. Because, the same way as when we love—we have a friend that we love or a loved one in general—we just want to be there for them. We just want to support them. And we’re not doing it because we’re expecting something back. We are doing it because we love them. So, ultimately, that turns into: I love plants. That’s why I am in that relationship. And if we expand and extrapolate this to, as I said, nature, so all of the aspects of this planet and the planet itself—being in a relationship with this planet in a reciprocal way means that we love being here. We love this planet, and you do not destroy, mistreat, abuse what you love, because that’s not love. And there is no trust in that. There is no reciprocity. So I think that what we then are seeing now in the bigger picture is a deep lack of love, on our part, for the planet and for this place that we are in.

EVLBut the reciprocity you describe is not an individual one between you and a specific plant. I mean, it can be. But you described a forest that you hadn’t probably spent a lot of time in, I’m imagining, communicating to you. So that reciprocity was not based on a relationship of trust between you and that forest; that relationship of trust was something that was greater than that particular form of a plant, be it a tree, be it a forest.

MGYeah.

EVLSo it seems that, you know, what you’re describing is an intelligence that a forest or a plant or a tree is able to perceive, that’s greater than itself; that it knows that you have, inside of you, the openness to value what it has to say, which is very different than building trust with an individual human being. Because you’re basically saying if you build trust with an individual human being, then you suddenly have trust with the entire human race.

MGYeah, I can see your point. I guess the individual relationship allows us to do the training of that muscle. And then you can start extending it beyond. Like we can train our loving capacity with our families because those are the ones that are closest and maybe sometimes easiest to love. But then that muscle can be applied, if it’s strong enough, in a more extended way, as you’re pointing to. And then yes, in theory, if you have enough training of that muscle, yeah, you should be able to love humanity as much as you love your son, your daughter.

EVLBut it seems like the plants are able to access your level of love, so to speak, quite directly.

MGYeah. And I think that’s why you mentioned the term “teacher” before. I think, in that sense, they are amazing teachers, because it’s almost the sensation that I get when I interact with them—especially when I’m having a hard time and I can’t quite, you know, I’m stuck in a very human space and I can’t quite work out what to do—it seems they, as you so beautifully pointed out, are very good at reminding us that what’s inside us extends and transcends the human form. And they can remind us of that because that which extends and transcends the human form is the same that we are seeing in the plants. There is something in the plants, or something everywhere in life—the life of it—that is transcending the form. And so it’s almost like a mirror that is showing you it doesn’t matter what you look like, but if you look closely enough, deep enough, you will find that there’s no difference. So, your form transcends, and you can love this entire planet. You can love all forms, plants, humans, other animals, because you recognize in them something that is you. But, of course, I think we are all working to get a little bit more enlightened, and as we know, it’s not a very easy task. But fortunately, we have so many teachers around us, non-humans especially, that can help us.

EVLBut you’re really talking about a universal spirit, whether that is considered love or, in other mystical traditions like in Daoism, it might be The Way.

MGThat’s right.

EVLAnd there are many names for this. In the Vedic traditions, they use “prana,” for instance—the life force that’s within everything—and that’s a language that is a universal language that allows you to both listen and then also speak to non-human forms of life.

MGI like that you’re mentioning the Dao, The Way, because I really love the fact that The Way that can be spoken is not The Way, because it really transcends— Again, there is this idea of needing to transcend the need of describing it and explaining it. And when you just feel, then you already know, which returns to “to know is to taste.” I can taste something and I don’t need to describe it to you for me to know. And even if I describe it to you, until you taste it, you won’t know. I guess there is this feeling of something bigger than us, wider, more open, and in a way formless, and yet all the forms are here, too. So yeah, that’s the paradox, right?

EVLMm. I mean, maybe to keep going with the more mystical, because, to me, there was a huge mystical thread in your book. Obviously it’s grounded in a real scientific understanding and experiments. But there was a very mystical experience also that was present there—your own, but also from the plants. And you share a teaching that was given to you by Socoba and the sacred jungle Tobacco. They communicated to you that “wisdom is in the oxygen, and the blood is the great connector.” And you write that this state of communion with the whole “is made manifest via your heart,” which speaks a little bit to what you were just speaking about with love. So, I wonder if you could speak a little bit more to that?

MGWhew. I think it’s actually quite simple, and I use this word not that lightly—simple in the sense of, we all are already all of that. And then because of some funny game that we are playing, we seem to find it interesting to complicate things and to make up stuff and imagine new ways. And sometimes, especially at this time, we are doing this in a quite extreme way. It comes to mind, I was recently speaking to a friend who was telling me about the work of an Italian photographer, who has now passed, and his name was Luigi Ghirri. He was a really amazing photographer, and one of the things that he was talking about, in a very prophetic way, in a way, he was imagining how in the future we would occupy the image and leave no space for the landscape. And of course, as a photographer, what he was prophetically already pointing at, was the fact of, you know, the selfie—now as long as I fill up all the image, all the space, you don’t even see where I am, it’s actually irrelevant. And then, as you know, there are even now tools where you can remove parts of the background that you don’t like in the picture. And so it’s almost like we are taking this desire of making things our way to such an extreme that we are replacing the real world and those relationships with an image and a representation of that—an image made to our liking, a representation made through our own filters and our own conditioning and biases, to the point that we occupy literally the entire space. And it’s a very dangerous place to be. We can see the results in the world.

And I guess this connection with different aspects of nature—beyond human nature, which of course is also nature—is a reminder not to go too wild or too far away from ourselves when we are getting all caught up in our creations, because we might get so self-obsessed that we forget about everything else. Literally we delete the background. And so the landscape doesn’t exist anymore. It’s being replaced by these representations. And that’s very dangerous, because of course it makes us feel very lonely, very unhappy humans. And then we go crazy, you know? And I think this is what we are doing. We are going crazy.

But fortunately for us, we haven’t deleted all of the landscape and these others are loudly speaking, I think, to a lot of people really. I receive a lot of messages from people saying, Oh, me too! Oh, finally someone said it! And it’s almost like we’re all in the closet thinking like, I can’t say that I’m talking to my plants, or my dog or my chicken. And yet everyone is doing it. So it’s almost like these others are slowly, slowly peeking into those pictures that we have occupied and saying like, Hey, we are also here. And in doing that, they are, in a way, dismantling a little bit of this egoic image of ourselves, the representation of ourselves. But also reminding us that, hey, you are going to feel lonely, but don’t be silly, just come back into the landscape a little bit, and we can be part of this together. And I think, in that sense, then we reconnect those molecules of oxygen and blood, which we share. They’re all the same molecules that keep remaking different forms, and so, in that sense, they are connecting us. But if we are holding our breath and trying to occupy the entire space, then yeah, it’s not going to work.

EVLNo, no. There’s another lesson that you described in the book that was given to you by Tobacco that I think points to what you were just describing as well, which was on the importance of surrender—how we have no control over the circumstances we face until we surrender the need to control them. Because you’re describing, also, control: when you fill the space with our own self-image, we’re controlling it. And you suggest we are collectively ready to shed this way of being; that it is time to overthrow our conditioned seeing for a “disobedient disruption”—I like that term—of the reality that has prevented us “from seeing the innovative solutions that could bring planetary well-being and peace into being,” which is a kind of phrase that you can very easily dismiss as a New Age platitude.

MGAbsolutely.

EVLBut, I don’t think it is when you’re describing it, especially from the context of where it comes from. So, tell me more about this surrender, this space that you were shown.

MGYeah, it’s very far from being New Age in the sense that, the people who know me, they know that I’m a very practical person. And so I get very frustrated when things remain too theoretical and in the thought world. I love the exploration, but then I personally need to get back to Earth and make it happen and materialize it here. So, when I speak of that surrender, I don’t say it metaphorically. I hardly ever speak metaphorically about these things. So, in my case, my personal case, it was about two years ago now I decided to leave academia because I realized that the work at hand that needed to be done to achieve this, or at least to move towards the goal that you mentioned the Tobacco speaking of, required me to embody that myself, in my own life. So, if the old system and the old structure doesn’t fit you, then you need to walk away and walk on and create a new structure that does fit.

So I left academia and I knew that that meant no income, probably not able to pay my rent anymore. My car broke down, so no car. And there is no more surrender than feeling as if your basic needs as a human might not be met, because it’s very scary. And of course I had plenty of panic attacks and anxiety at the start, but at the same time, there was a part of me that felt like this was the right direction, I’m not alone, and I’m being nudged on.

Now, two years on, as you can see, I’m not exactly starving, or I don’t look like I’m dying of anything because of that. And, if anything, in that saying of, “Okay, I am letting go, and I’m doing it right here,” then life responds tenfold with what is needed. And so, somehow, the vision that is moving me now—which is more of a global kind of project—is constantly asking me to surrender. And every time I want to hold on a little bit, or control things, or get frustrated because I want things my way—which, of course, is normal; I’m totally human—things suddenly stop. And I’m learning to feel that, like, oh, I just tried to control things again. And so I literally have to: Whew, okay, just let it go again. And in that moment, immediately things start moving again. And, you know, from the outside it will look like magic. From the inside, sometimes it does look like magic—it’s like, whoa, how does this happen? But I’m getting used to this movement—again, it’s the posture of like, okay, I actually don’t need to control anything. When I do control, because, I guess, I’m a bit freaked out by not knowing what’s happening, I’m being informed immediately that that’s not how we operate. And so there is this constant feedback.

Again, I have met a lot of people who are going through a similar process in their own lives and this idea of like, I have no idea what’s going on, I have no idea what I’m doing, but I’ve been nudged to go this way, and yes, I’ll go that way, even if I don’t understand—I think that’s a very powerful thing, and it’s happening a lot. So that change that the Tobacco was inspiring—it’s in progress, it’s a work in progress. And of course it’s almost like, if it was screaming out loud, “I’m doing this and this is how it works, and look at that,” it would risk turning itself into exactly the structures that are not working for us anymore. So this is a more quiet and subtle work—very pragmatic, very grounded, very real. But at the same time, it doesn’t need to advertise itself until it manifests. And then everyone will see and it’d be like, Oh! When did that happen? That looks good. Oh, I’ll go that way too. And so hopefully it will inspire others who were kind of already considering, yeah, I need a change, life like this is not a sustainable life, this is not helping me, it’s not helping the planet. And we can’t force people. Surrender is exactly the opposite. It is not force.

So, I guess we can only—at least this is what I’m learning—its like, if you want to change the world because you don’t like it as it is now, you just start walking, start walking the other way. Start walking the path that you think is a different way of being here. And then don’t worry about what’s happening with that. If someone sees it and it feels inspired, great. If nobody cares, fine too. You just start walking. And so, in that sense, again, there is a surrender of not expecting anything either, and not expecting anything beyond what it is that you are actually doing in that moment.

EVLHmm. And did you move away from academia because you felt it was too rigid and you were unable to actually do the work you were being called to do by having to play by those rules?

MGYeah, pretty much. And also I think I really felt this wasn’t like, I’ve had enough of you guys, I’m fed up, and I’m going. That wasn’t the attitude. It was actually very, Oh wow, okay, this is finished. So it was quite peaceful, and it was very clear, and I was quite at peace with the idea; like, Oh, okay, whatever I could have inputted in that system, I feel I did, and now it’s time for me to move so that the rest of what it is that I’m supposed to do can happen. And, it’s ironic, because I am in conversation with some universities to do part of the project that I’ve been developing for the last two years, and I find it funny that of all the people and of all the spaces, it would be academia that would come back and say, we would love to do that with you. And I was like, really? So we’ll see. I can’t really talk about it in detail, because as I said, it’s very quiet, it is a very delicate baby that we are nurturing. And yeah, I’m very excited because it’s been teaching me so much about surrender and magic and awe and reverence.

EVLWell, there was another teaching or sharing from the Tobacco plant, which I was, perhaps, most moved by. There were so many teachings that were imparted to you that you described in your book through your experiences, and in this one Tobacco spoke with you about his ability to heal humanity of its greatest pain, which he named as the pain of separation from God—or the universe or a greater wholeness, whatever label one chooses—through remembrance, which I was very moved by, because in my own mystical tradition, in Sufism, remembrance is the journey back to the recognition of that wholeness, whether you call it God or Mystery or Allah. And Tobacco said: “In each moment, humanity can open its eyes to close the rift that separates it from the whole by realizing that there is no rift at all. This realization heals the root cause of humanity’s pain.” I mean, when I read that, I was like, I could be reading from Meister Eckhart or Buddha or Ibn ‘Arabi—the list of great saints and mystics goes on that could be sharing that. And this came from a plant. And I find that very humbling, because it perhaps turns on its head, so to speak, this notion of who imparts mystical wisdom of that level.

MGYeah. And I have a suspicion that all of these people might have heard the same others speaking to them.

EVLSure. They just didn’t call it a plant.

MGThat’s right.

EVLThey heard it as God or the not-knowing mind or the emptiness or their own divine nature.

MGYeah, but the interesting thing—returning to the experiment in the Dolomites—one thing that I didn’t share, which is, for me I’m still digesting it. At the end of the experiment, the same way as at the beginning, I asked permission to be there, at the end of the experiment before we left the site. I went for a walk and I just wanted to thank this forest for allowing us to be there, to collaborate. This is a place that was quite badly devastated by a big storm a few years back, so there were a lot of areas of the forest that were like completely destroyed, annihilated, trees down. So my human eyes were looking out and when I wanted to say thank you for having us, what I was seeing was all this destruction, and I was like, oh, so much pain. And I started crying because of the pain that I was looking at. And then I heard this voice, it was a voice, it was a sense of the land Herself—I mean, the Romans would’ve called it the genius loci, but it’s the spirit that embodies that land at that place. And he was like, No need to cry; everything is precisely as it’s supposed to be. And then he shared a lot of things.

And when I shared this back with a friend that was part of the team, he said to me, “Oh my God, Monica, do you know I have a book of fairy tales and that thing that you’re saying, I read it in this book.” I don’t know the book, so we come back from the field and he gives me the book of the fairy tales, and I look, and it’s like, oh my god. So the same words had been written there by someone before, before, before me. When I went back to the area—just a few months ago I was there—I asked around, Do you know any fairy tale story that has this theme in there? And there is one story about a very old woman who knows everything that has been. And in the story she tells, as part of what she’s sharing with the humans, she’s saying exactly the same words that the land gave me.

So, I know this sounds, again, it sounds a bit crazy, but for me it feels like someone else, ages ago, sat on this land and this land shared the same message with them. At that time, they put it as a fairy tale. At this time, I’m writing it as a little song for my ukulele, which is what I did. But it’s the same message. So there is someone that is very old, and in Australia it would have the name of “Country,” there is someone that is very old who also holds the knowledge of all the past that has always been, and it has this perspective that is so much broader and wider than the little one that we have as humans—because our lives are relatively short—and who can say from that perspective, Don’t worry, we’ve been through this before. I’ve seen this before. You little humans cry for something that you don’t have to worry about. And in that sense, it gave me, also, a sense of like, Wow, I’m connected with a past that is so deep that I can’t even imagine it. So when we talk about ancestors, it’s like, this is more than ancestors. This is like time itself is the ancestor. And then also hope—this feeling of like, She, as the Earth, knows what She’s doing. She’s The Great Experimenter. She’s done experiments before and this is just another one of Hers, and it just happens that we are seeing parts of it. But again, because we don’t have the entire picture, we do not know what’s going on, and we are trying to make sense of the little bits that we have.

But in fact, what I learned from this forest was— Actually the forest that I called “forest” was a plantation. It was a monoculture. And when this storm came, it cleared a monoculture, which is actually not a good thing to have in a place that is supposed to be much more biodiverse. And what emerged from that disaster was that suddenly these species of trees that nobody had planted, apparently, started to emerge. When I spoke to the rangers, they were like, Oh, you know, we have all of these trees coming up and they are the perfect species to be here, especially in view of the climate changing. And I’m like, Yeah, because She’s done it before, and She knows what’s going on. And so it gave me this sense of empowerment, really, because often in the face of this big changing climate and disaster at the environmental, planetary level, I think a lot of us feel hopelessness and grief. And instead it gave me like, Oh wow, okay, so there’s someone bigger than me—much, much bigger than me—that got that. I got it. And it feels good.

EVLMonica, it’s been a real pleasure speaking with you today. Thank you so much.

MGNo, thank you for the beautiful questions and for allowing me to splurge around all of these themes.

EVL[laughter] Splurge away. [laughter] Thank you. All right, bye-bye.